A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I posted “I Began to Long for a Catastrophe” for The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers to this Substack. It concerns Nathaniel Hawthorne’s third novel, The Blithedale Romance, a dream-like narrative of morally unreliable narration about radicalism, occultism, and aestheticism in American life. Hawthorne is probably the most underrated classic American writer—the whipping-boy of high-school students whose teachers failed to convey (or perhaps didn’t even understand in the first place) his dizzying ironies—and The Blithedale Romance probably his most underrated book. In the episode I make the case that Hawthorne is not the genteel moralizer of the pose he admittedly adopted, that he has more in common with Kafka and David Lynch than with anybody else in the 19th century (save perhaps the similarly [self-]underestimated Dickens). The Blithedale Romance is only a failure, as some critics claim, if you were expecting an American Fathers and Sons and not an American The Trial. Please offer a paid subscription today for similar unexpected observations, and for a burgeoning archive that already contains 19 weeks on modern British literature from Blake to Beckett, eight weeks on the work of James Joyce with a focus on Ulysses, and four weeks on Middlemarch. This week, we begin a three-part sequence on Moby-Dick.

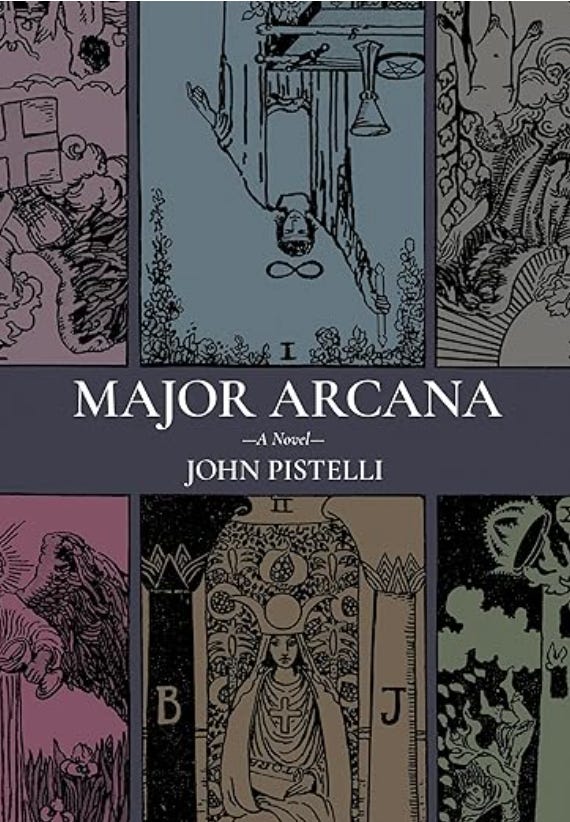

I also discuss in the episode Hawthorne’s profound influence on my new and forthcoming novel Major Arcana. Not for nothing is the primeval-forest-set Chapter 3 of Part Two entitled “Moral Wilderness,” a phrase from The Scarlet Letter. To witness my radical reinvention of tradition, I invite you to pre-order Major Arcana. The beautiful Belt Publishing edition arrives the day before Shakespeare’s birthday in 2025. Paid subscribers to this Substack can also access the original serial of the novel, complete with my audio rendition, if you can’t wait to read until next year what Ross Barkan has called “perhaps the elusive great American novel for the 21st century.”

I am also honored and grateful to announce that after “discovering” the astonishing oeuvre of Bruce Wagner earlier this summer—actually discovering that I’d known it in some respect since my early childhood—I followed an intuition about our aesthetic affinity1 and sent him the novel. He responded with a very generous endorsement:

Major Arcana is a bravura, hallucinatory tarot of art, madness, and the fatal poignance of being alive. To read it is to hold the heart of the world in one’s hands.

For today, and for the benefit of my many new readers, something I meant to write last week on the occasion of the release of my “devastatingly generous” piece on Madeline Cash and Honor Levy’s short fiction in the Mars Review of Books2 and of my Invisible College episode on short-story theorist and writer extraordinaire Edgar Allan Poe: an index to my own short stories. Please enjoy!

Short Order: Collected Stories

From about 2012 to about 2019, I was an assiduous writer and submitter of short stories, because I thought that was how the game was played. I was even reasonably successful: I published almost every story I wrote in a journal, some small and fly-by-night, and others (Glimmer Train, Five2One) relatively big. I prefer novels to stories, however, and I share in part Naomi Kanakia’s judgment that “the literary short story is an empty formal exercise”—or, as Elif Batuman once more dramatically asserted in the borrowed and apocalyptic words of Georg Lukács’s Marxist criticism, “[the short story’s] existence [has] already been condemned by the historico-philosophical dialectic.”

Surely the literary short story is among the most calcified of literary forms. The innovations of Flaubert, Chekhov, and Hemingway have hardened (via pedagogy) into a genre as rigid as—maybe more rigid than—the mystery or romance novel. Yet, if we are not little Lukácses hunting for kulaks to liquidate, we will want to see the form revived (if possible) rather than simply abandoned. We can take heart, therefore, to see the next generation of writers trying new things with the form. I tried new things, too, though the dead hand of Chekhov probably lingered too heavily on me as on others.

I present these stories, all of them free to read online, to my new readers so that you can, if you like, judge for yourselves.

“Terminal Girls” — This is the first of two stories with “girl” in the title. In neither case was it my intention; in both cases, the editors were conscious of living, back in the early-to-mid 2010s, in the era of Gillian Flynn and Stieg Larsson. My original title for this one, admittedly too cute, was “The Rise of Professor Lazarino.” I was inspired by something a religious studies professor once told a class I was in: Christ waited so long (three days) to resurrect Lazarus that Lazarus would have spent the rest of his life a stinking, walking corpse. (“Imagine sitting next to him on the bus,” the professor quipped, an image reprised in the story.) I also had the then-zombie craze in mind, The Walking Dead and all that. And sexual fetishism—along with parapolitics a persistent motif in my work readers tend (understandably) to ignore with studied politeness. I still think the fetish I invented in this story has not yet fully materialized online, surprisingly enough, but maybe I just haven’t looked hard enough. It’s obviously an allegory about leaving academia. It’s also about what it takes to be an artist. It’s the first of my works to be pulled into the desert at its conclusion. I wrote it as a mission statement:

Her heavy eyes began to close, but she kicked her legs and slapped herself awake. A poem a day. Otherwise, she would be just another boaster, just another poser who proclaimed herself an artist but had empty hands to show for it. She sat up and took out her notebook. Her life these days seemed to cry out for a ballad, something about desolate landscapes and languid, uncertain adventures.

“White Girl” — The second “girl” story. My original title was “An Unsigned Confession,” which I thought sounded Russian and 19th century. People have expressed surprise that it was written and first published in 2014. It appeared in a very small journal, whose fiction editor, a young woman about a year out of college, provided the most intelligent edit a piece of fiction of mine has ever received. She was probably right that “White Girl” was the more arresting title. I intended not so much to satirize as fully to inhabit and take to its logical conclusion what we were not yet calling “wokeness.” Expat Press published it again in 2019. In 2020, it would have caused total cancelation if published fresh, mine and the journal’s. Now, a decade after I wrote it, it might be considered, rightly, something of a cliché. The high-school folie à deux it dramatizes looks forward to Ash del Greco’s gender-obliterating gnostic hemi-, semi-, demi-romance with Ari Alterhaus in Major Arcana. The first line is more theatrical than I usually like a first line to be, but whatever works: “My father was a cop. That’s why I had to shoot him.”

“Iconoclasm” — A flash-fiction prose-poem about ISIS-as-art-criticism, about how abstract modern art is the most reactionary traditionalist religious art ever made. Mostly I just reveled in describing the destruction:

One man with a machine gun mowed down a line of sluttishly bare-breasted Roman goddesses and then a row of barbarously leering Mexican deities; then he assassinated a foolishly smiling Buddha, his hand upraised, counseling peace. An anti-matériel rifle was required to put a bullet in the head of Rodin’s nude bronze Balzac; the man who pulled the trigger fell back from the recoil, cackling. A girl in marble lay prone, her bare bottom and the soles of her feet upturned insultingly at the invaders; they took her to pieces with hammers.

“The Embrace” — My battle-of-the-sexes story, my Lovecraft story. (I still don’t like the title, but what else was I going to call it? “Octopussy”?) It’s about being an adolescent, being on vacation. You’re too old to hang out with your mother, but what else, being still a minor, are you going to do? I think I wanted the narrator to have no specified gender at first. She might also have been a boy, which I also considered, but I thought the resulting emotional configuration would seem too redolent of Oedipus and therefore slightly beside the more universal point I was trying to make. Thus, I chose a somewhat asexual- and agender-seeming girl narrator, which probably helped the story’s acceptance in a rather bien-pensant journal, then new. The central scene is probably the best I could do with the objective correlative, except that my narrator actually picks the thing up and attaches its flesh to her own, which I suspect Chekhov would have balked at as too melodramatic. (This is what comes of dying almost a century too early to grow up on Cronenberg movies.) Not using the word “octopus” now strikes me as a cheap gimmick, however, taking Shklovsky’s praise of Tolstoy—

Tolstoy makes the familiar seem strange by not naming the familiar object. He describes an object as if he were seeing it for the first time, an event as if it were happening for the first time. In describing something he avoids the accepted names of its parts and instead names corresponding parts of other objects…

—too literally. But I love to describe uncanny spaces, and I think the eerie underwater restaurant in this one is pretty haunting:

The bar in the center of the blue room was shaped like the thick, scalloped lip of a clam shell, and the bar stools were fashioned as jellyfish heads supported by thin metal mimickings of radial canals (being fifteen years old and in high school and an unusually avid reader of my science textbooks, I had such precise terminology at the ready). The tables in the main room sat next to windows that looked out into the glowing blue darkness and lazy detritus of the ocean. But the most prizeworthy tables were stationed in eight transparent tunnels that extended out like arms from the hub of the main room. In the tunnels, you could look above you to the high-drifting rays and the schools of fish darting and flicking like a single organism; if you could stand their judgment, you could be watched by the wary, resentful co-lifeforms of the dinner on your plate, inwardly furious citizens of an occupied city. Sitting perfectly still, eating your swordfish or lobster, you rode in a triumphal car through the ocean.

“They Are in the Truth” — The first in a loose trilogy coming to terms with the end of academe. This is a pure Hawthorne-Kafka parable-nightmare, so chastening I cringed to write it and think you’ll cringe to read it, my fullest consideration of the problem that you may not be the genius you think you are and that therefore you must be condemned for the term of your natural life to a normalcy you will actually find to be your truest home:

“But we figured if you were a genius, we’d have heard about it already,” LeBon said. “You like to think you might be. You like to hang around in a genius-type atmosphere, because you’re too good for any other. But what—I mean, really—what the fuck are you doing with your life?”

“Patronage” — The second in this loose post-academic trilogy, funnier and more gentle, if its attempted murder scenario is more gentle. I once read it aloud to a creative-writing class I was invited to speak to and had to give them permission to laugh at the funny parts of the histrionic narrator’s récit, so solemn is the academic atmosphere. (They weren’t humoring me, so to speak; they eventually did laugh at the right parts, the parts I meant to provoke laughter, though it would have been amusing for a different reason—and I was prepared for this outcome, too—if they’d just laughed at random.3) This Santa Monica fever dream is really an answer to “They Are in the Truth”: a much less mortifying, though still somewhat mortifying, wish-fulfillment fantasy about what might be done with the overproduced elites, mentorship recast as domestic service:

“But you show a certain spirit,” she continued, musing. “The great ones were crazed and foolish, to be sure. A handful were not above violence, even murder. Suicides were a dime a dozen. ‘And each man kills the thing he loves.’ Many students have written superb final essays and gone on to graduate study, but you are the first to return to murder me. It makes me consider that you might in fact be above the common run. Marked out, as it were. And after your pathetic tale, I can hardly send you back to your vulgar mother, to a grease-walled kitchen, can I?”

“Right Between the Eyes” — This novelette is the nastiest and most savage thing I’ve ever written. Both for this reason and because of its length, I never sought publication, but I did put it on Substack a few years ago just to exorcise the narrative. I based it, the third in my loose post-/anti-academic trilogy, on a nationally viral Pittsburgh-based news story of 10 years ago: an elderly adjunct professor died in poverty, inviting leftist sympathy, but she was later found to have been a fierce Catholic reactionary, provoking leftist denunciation. The bare facts as outlined are ironic enough, but I infused them in this narrative collage of voices-inside-voices with a probably too-personal and too-incandescent rage. Nevertheless, the little fantasy I spun about such a woman’s life is an oasis of poetry in a desert of invective; I even had Borges show up:

They held modern art, high or low, in contempt, and gently teased the old homosexual Soledad for his interest in the effete Argentine fabulist. The professor had sent them once to pick up the great Borges from the airport and drive him back to the university for a lecture, and they agreed that his vaunted skepticism and over-estimated erudition represented the refined play of an aged blind schoolboy pleasuring himself in public with the toys in his sightless mind. When this decadent age gave way, whether to the renewed authority of the Church or to international socialism, the arts would return to the serious and beautiful representation of typical sublunary natures.

“Sweet Angry God” — My favorite of my own short stories. It does obey “iceberg theory”-type rules in spite of their over-familiarity and decadence. If “White Girl” was a little early in 2014 with its murderously woke high-schoolers, then this story, written in 2015, was also a few years early for the answering Red Scare girl archetype, but that’s who it’s about, substituting Calvinism for Catholicism. I don’t know if the five weeks I once spent in L.A. has earned me the right to this exercise in Southern California Gothic, but I did enjoy writing it; and I don’t know if the cancer-and-cunnilingus sequence is in poor taste—with my eye on that iceberg, I never use the word “cancer”—but I still find it rather sweet and moving. It’s about the end of the world, the way the world is always ending, every minute of the day:

It was going to be another drought summer. Even the pink-walled motels beneath the highway looked as if they were made of sand. I read on my phone that coyotes in the canyons were becoming a problem, and even the children of the stars could have their arms or legs chewed off. Eventually the sand and the teeth would reclaim this city. The dunes would shift in the wind over strewn limbs. Eventually death would leave its scar on my baby sister.

And those are my collected short stories so far. Maybe someday I’ll put them into a book—I designate Right Between the Eyes as the collection’s title—but you can read them all for free online right now. Please enjoy—and let me know what you think before the historico-philosophical dialectic condemns us all.

Candidly, when I was on the total and absolute outside of the literary world, I was very suspicious of all these notables blurbing each other’s books, and I am still wary of the first novel with the overripe blurb from the budding author’s MFA advisor. And yet, now that I’m a bit further along, I understand the more organic process by which one earnestly seeks out one’s semblables and frères. I am the exact type of mark, by the way, who is sold a book by the blurbs; I read those, scanning for the unpredictable but apt comparison (“like an episode of Girls written by José Saramago”), not the overly detailed plot summaries. (“Like an episode of Girls written by José Saramago” is a line from the pitch I sent to literary agents for Portraits and Ashes back in 2013.)

I haven’t forgotten that I’ve pledged to review several books readers have sent me for consideration, two of them short story collections. I will get to them, I promise, in the coming weeks. Speaking of Madeline Cash and Honor Levy in the meantime, though, I ran across Anna Krivolapova’s Incurable Graphomania in the library this week, a collection superficially in the same vein as the other it girls’. I read it because I’d heard the author on the podcast circuit and was intrigued by her infusion of parapolitics into the genre of the 2020s literary short story as practiced by Cash and Levy. Here, for example, is a passage from Incurable Graphomania:

Look up:

MK Ultra

Artichoke

Bluebird

Collins-Armirgo Project

Gladio

Danny Casolero and the octopus

Delgado and the bull

Estabrooks/Delgado/Verdier

An avowed child of Dick, Didion, Brautigan, Dostoevsky, and Sartre, Anna Krivolapova writes stories that are if anything more serious and accomplished—if always mordantly funny—than those of her contemporaries, because her stories artfully include more of reality. This is an aesthetic point, not a political one, but Krivolapova discloses through narrative and characterization a political reality—an emergent commercial totalizing state-corporate techno-feudalism in which everything is trafficked, especially the flesh and the soul—that should not go unspoken in our literature, but which often does go unspoken, or distorted into trivia, due to our literature’s sick vassalage to a dominant political party and to the clerical class that services the empire. As she says in a recent Substack interview:

So I think there’s an overemphasis on the wrong things when people want to become writers. Maybe they were good at it in high school. Maybe they have great syntax or they have a knack for clear description. But they don’t have any stories. They just don’t have stories. And I think that’s the biggest issue today: there are a lot of wonderfully technical writers. People who went and got the degree and studied, but they just don’t have any stories to tell. And so to loop back what we said in the very beginning, they start to tell their own story. And that’s not always compelling.

In this spirit, she evokes histories coiled with awful potential energy between tersely sensuous lines, as if there were indeed still a historico-philosophical mission for this apparently superannuated genre. A paragraph plucked almost at random:

Mila had to sell her mother’s opal earrings to make enough money to leave Brooklyn when her adoptive parents found out she was 22, not 17. She thought she’d find someone sympathetic in Brighton, the Russian dollhouse slapped together by bitter immigrants in the Fascist 40s. Where tourists swish around a replica of the Nylon 90s. Where expats spit between their Nike slides and swear they’ll never return to Eastern Ashtray, while they fully recreate it on every block.

She might remind me more almost of Bolaño than anyone else, in spirit if not style, a spirit of “romantic anarchism” dancing with wild elegance against the encroaching politics and metaphysics of death.

You can read the personal-surveillance nightmare “Jersey Devil’s Breath” online, but you should try to find the whole collection so you can also read the poignant hallucination “Some Like It Orange,” the devastating nightmare of sexual predation “The Taco Bell in the Center of the Pentagon,” the extraordinary parapolitical fantasia “The Reagan-Blair Manifesto,” the Dostoevsky/Sartre homage “Chapter IX. The Devil. Ivan’s Nightmare,” and more. A truly great collection.

Recently, a reader wrote in to my super-secret Tumblr to ask, “What do you consider some of the best funny works of literature? (Not necessarily ‘funniest’, but best works that are funny); your canon of humour.” I repost my excessively candid answer here:

My favorite style of humor—and humor seems more personal as well as more culture- and time-bound than seriousness—is arch and dry wit. I prefer this to a zany, slapstick, or gross-out style. Thus for humor if not for other artistic virtues I prefer Austen and Wilde to Dickens, for example, Emma and The Importance of Being Earnest for preference. Ulysses is the encyclopedia of every kind of humor as it is of every other kind of thing, and the funniest parts of Ulysses are the funniest parts of any novel ever written. Beckett, as Joyce’s devoted student, and perhaps a disguised descendant of Wilde too, is hilarious in his plays’ bleak repartee, though he might lean too hard on the scatology. Works before the 19th century are perhaps too distant from us to be funny, exactly. The Decameron, The Canterbury Tales, Don Quixote, Candide, Gulliver’s Travels, Tom Jones all seem somehow too cruel, as Nabokov observed of DQ, to the modern sensibility. The deadpan irony in Dante’s contrapasso is somehow funnier than all of those, somehow more forgiving in its cruelty. Shakespeare may be funnier to us in the tragedies, where the jokes flash like lightning in the darkness. Is anything funnier than the cosmic joke of Hamlet? Whereas I can’t share the worship of Falstaff. Tristram Shandy is closer to us, but strained, over-familiar, like a beer-swilling uncle clapping you between the shoulders; I feel the same about the humor in Moby-Dick; both of those books are grab-bags of dick jokes. Henry James is funnier than he gets credit for being, especially in dialogue. To return to the 20th century, the aforementioned Nabokov is obviously funny; I like him better the subtler he is, as when Humbert describes Charlotte Haze descending the stairs and enumerates her features as they become visible to him “in order,” from her feet up—as if any other order were possible! Pynchon? Too stoner for me; I prefer his elegiasm, though The Crying of Lot 49 always makes me laugh with its zaniness so adjacent to tristesse. Gore Vidal’s critical essays might offer the acutest wit of the 20th century. Roth is funnier the further he gets from sex, ironically, and Operation Shylock is immensely funny at micro and macro scales, the height of die-laughing political comedy. Humor being, as I’ve said, personal and local, I have described DeLillo’s White Noise as the funniest novel I’ve ever read, and I stand by that, even if the world it affectionately mocks is no longer quite ours, and even if I am affected in this instance by some latent Italian-American consciousness and its dry skepticism.

(I see from the inadvertent psychoanalysis in the above free association that there are two kinds of humor: one moves toward the body and its grosser functions as a source of laughter and the other moves away to higher levels of abstraction upon the world. I obviously prefer the latter, humor as high-minded irony, as pointed wit, a defense against sensation. The unruly body, the “lower bodily stratum” as I think Bakhtin called it in his study of Rabelais, whom I still need to read, is likelier to show up in my constellation of taste as a source of anxiety, tragedy, or, at its best, forbidden or abashed and therefore serious eros. Which self-analysis I’m sure a reading of my archly witty novels—they’ve been described as body horror—will bear out. Those who have scrutinized my sensibility as “very Catholic” will have something to say about this, given Catholicism’s intensely abstract, paradoxical, and therefore inherently witty theology, based in its turn upon an equally intense and deadly serious affective veneration of the wounded corpus. Why else find Dante funnier than Boccaccio?)

I meant to say at the time that Right Between the Eyes is my favorite of these, and in some moods my favorite of your fictional output. It’s got almost all your themes-Marxism and orthodox religion as comparable demand systems, the protagonist who can’t quite believe in them, a simultaneous partial rejection and yet in the end re-commitment to bourgeois normativity “we plan on marrying in the spring” etc. But for the uncharacteristic nastiness, it could almost be an introduction to your fiction generally.

I just finished reading "They Are in the Truth." Indeed, realizing that one is not a genius does play a role here. But I think the main focus is on the clash between sheltered intellectuals and "men of action," and genius is not necessarily a part of that. The story it most reminds me of is "The South" by JL Borges - it even strikes me as an extended, black-comedic riff on the themes of that story.