In 2024, I will continue to write Weekly Readings posts, plus the occasional literary essay, for free subscribers to this Substack. Paid subscribers, however, require a new product or benefit in exchange for their patronage, since my serialized novel, Major Arcana, will be completed soon. In the following free post, I announce what my current and future paid subscribers can expect in the next year here at Grand Hotel Abyss. If you’re already a paid subscriber, thank you for your support! If you aren’t, please join us!

The institutions, we hear, are in decline. I wrote last year about the decline—though the New Yorker more alarmingly called it “the end”—of the insistution in which I myself participated for a little over two decades: academic literary studies.

Like many people who have jumped or been thrown out of these burning buildings, I’ve thought about how we might rebuild them virtually, here online. I recall the narrator’s joke about the corruptions of the church vis-à-vis the requirements of the spirit in DeLillo’s Americana: “It’s like the lying and cheating General Motors does. You still need cars.” I don’t have a car or a job in an English department, but we still need somewhere to go to deliberate collectively over our literary heritage, because it has, to a hideously unremarked degree, shaped our world. I specify “our literary heritage” and not a hodgepodge of “culture.” I recall the narrator’s joke about cultural studies in DeLillo’s White Noise: “There are full professors in this place who read nothing but cereal boxes.” We will not be reading cereal boxes here.

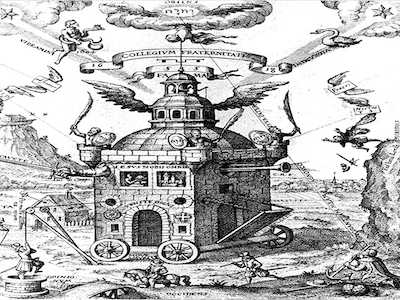

I first proposed to offer online courses last spring under the rubric “The Invisible College.” Though I am an uncultured swine reared on comic books and consequently pulled the phrase from Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, Morrison derived it from the disputed or semi-apocryphal networks of early modern natural philosophers and esotericists who were the occult precursors to the Royal Society. I just thought it was a good name for an online school—literal, in that there is no physical college, but with a figurative ring of the conspiratorial and the spiritual.

I didn’t get around to offering such courses in 2023, however, since I was too immersed in writing Major Arcana. Now that I’m finished writing Major Arcana, however, with the serial set to conclude before March, I have determined that The Invisible College will be in session on this Substack for almost the entirety of 2024, from mid-January to mid-December, with brief summer and winter breaks.

In truth, I would prefer not to think of what I’m about to offer as “courses” at all, or to think of myself as a pedagogue. The College will be “Invisible” because it does away with the often stiflingly hierarchical atmosphere of academe. This atmosphere is no less stifling in the era of grade inflation and rampant “accommodation,” and may be more stifling, since the Visible College dissimulates as specious “justice” and “accessibility” the hierarchies it still upholds.

What am I offering? Paid subscribers to this Substack will receive access to weekly lectures1 (in audio/podcast format with accompanying pdf slideshows) on three separate courses of reading divided (jocularly, I hope) into “Spring Semester,” “Summer Reading,” and “Fall Semester.”2 Here is the syllabus, which I will explain narratively and discursively below:

The spring semester of The Invisible College will be a survey of modern British literature, from about 1792 to about 1945. We will read four short- to medium-length classic novels (Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Dickens’s Hard Times, Conrad’s The Secret Agent, Woolf’s To the Lighthouse) and four classic plays (Byron’s Manfred, Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession, Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot), all of them spaced out in the schedule to allow enough time to complete. But we will especially focus on the period’s most renowned poetry, from Blake’s inception of Romanticism to Auden’s recession from modernism. Poetry in general is probably now understudied, and this body of poetry is especially neglected despite its pervasive influence on the literature and popular culture we do still read and view.3

I feel strongly, in fact, about the importance and relevance of modern British literature, though I only got to teach the course (familiarly called Brit Lit II) twice despite its being, on paper, my academic speciality. Once a staple of the English curriculum, it is now offered less than ever on the dubious theory that it lacks relevance to today’s students, especially in the U.S., sometimes with customary reference to identity politics. The subject has less glamor, in or out of academia, because other topics seem more superficially immediate to contemporary American life, but this presumption is completely false.

Because 19th- and early 20th-century Britain was ground zero of the Industrial Revolution and its social fallout, of liberal-vs.-conservative democratic politics, of Darwinian science and its effect on culture and religion, of modern imperialism and the resistance thereto, and of modern gender and sexual politics, the British writers of the 1792-1945 period were among the first generations to confront the questions we still struggle to answer. We can see this in the critique of industrial and imperial society in Wordsworth and Dickens and Conrad, the reflection on the role of the artist under scientific and capitalist hegemony in Shelley and Tennyson and Wilde, the examination of gender and marriage in Austen and Shaw and Woolf, the reassertions against modernity of both religion and magic in Blake and Hopkins and Yeats, and more. They are probably the most relevant writers in the traditional literary canon.4

Today, these writers are sadly less read than later theorists who reprised and repackaged their insights, often in forms less complex and arresting. The partisans of fashionable theory on left, right, and center, not to mention both the elitist and populist literati from Brooklyn to BookTube, either ignore these major writers or condescend to them, while their only champions tend to be historicists inside the academy and hobbyists outside of it, both groups tending toward an antiquarianism that makes most modern British literature look misleadingly quaint and cozy rather than the urgent and ultramodern affair it really is.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is the Byronic hero philosophized; Bataille’s transgressions were inspired by Blake’s bibles of hell; Giorgio Agamben’s and Byung-Chul Han’s critiques of modernity are no more intelligent but may be less moving than are Shelley’s or Lawrence’s; French Theory’s ideas about language and subjectivity in general grow straight out of Joyce and Beckett; Tennyson and Auden wrestled with faith and doubt in a secular world long before the New Atheists or the Integralist Catholics; neither TikTok witches nor TikTok decolonialists have much to teach Yeats; Wilde is probably the reason you call yourself queer; if you’ve just converted either to socialism or to Catholicism or to both, your first stops should be Shaw or Hopkins, not Jacobin or Compact; we wouldn’t have modern lyric poetry in any of its modes, expressive or dramatic, without Wordsworth and Browning; Austen and Dickens invented the modern popular novels of courtship and of social justice (respectively), even as Conrad and Woolf were at the forefront of experimental fictional techniques like fragmentary storytelling and stream of consciousness narration still in use today.

At the risk of overstatement: to fail to read this body of literature is literally to fail to understand either your language or your life.5 In saying this, I don’t mean to suggest that other traditions, periods, and writers aren’t equally worthy of study, only that this one has fallen into undue neglect, especially by those who should most be familiar with it—those of us who are its children and heirs, whether we know it or not.

Following our spring semester, we will enjoy summer reading. Summer reading, I’ve always found, is best pursued with a long novel or two to go with the long days. The summer session offered here in The Invisible College will grow naturally out of our prior survey of modern British literature, since we will read arguably the two best and most significant Irish and English novels of the period, usually also said to be among the best novels written in English: Joyce’s Ulysses and Eliot’s Middlemarch. We will read Joyce’s modernist mock-epic first because Ulysses is set in June, taking a leisurely six weeks over it, and then embark for four weeks on Eliot’s Victorian realist panorama.6

Also counted among the greatest novels in English, as well as the “Great American Novel” itself, is Melville’s tragic epic Moby-Dick. The Invisible College’s fall semester, focused on American literature from Romanticism to modernism will include a three-week reading of Melville’s masterpiece. On the way to the whale ship, we’ll begin with the Transcendentalist movement: we will examine those essays of Emerson said to define “the American religion” and explore Thoreau’s and Fuller’s social critiques with their implications for nature, society, gender, and politics in the U.S. Next, as a prelude to Melville’s Great American Novel, we’ll enjoy the early American Gothic and Romantic fiction of Poe and Hawthorne. Then we will read Moby-Dick itself over three weeks.7 Following Moby-Dick, we will indulge in the wildly divergent experimental poetics of the century’s two greatest American poets, themselves the heirs to Transcendentalism, Whitman and Dickinson. Then will move on to the definitive realist fiction of James in the form of his novel, The Bostonians. From there we will explore modern American poetry in the works of Frost, Pound, and Stevens and read three great modernist American novels: Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury.8

The relevance of these works to life today requires less of a defense that contemporaneous British literature, especially if we are Americans, but they have been dulled by their status as classroom classics—either fusty antiquarian icons to be revered or oppressive dead white men to be toppled, the searching radicalism of whose vision has in either case been lost.

If 2024 goes well, and I think it lays a good foundation for future study, I will continue in 2025 with expansions in time and language beyond Anglophone literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Prospective 2025 topics may include: translated literature in all periods, e.g., Sophocles, Dante, Goethe, Dostoevsky, Ibsen, Mann, Borges; British literature before Romanticism, especially Spenser, Shakespeare, and Milton; and more modern and contemporary British and American fiction and poetry.

In the meantime, please matriculate today. (Am I going to belabor this college metaphor until you want to die? Élèves, I am.) I have designated our first meeting, on the always interesting topic of the visionary William Blake, for Friday the 19th of January. You will want to be a paid subscriber by then—and maybe you could even tell a friend too. I’ll see you there!

I plan to post these every Friday. They will be halfway between formal academic lectures, like the ones for University of Minnesota undergraduates you can hear on my YouTube, and the more freewheeling and informal style I used on Grand Podcast Abyss. Frankly, it’s not not going to be podcast. People say the podcast market is oversaturated, but I have faith that quality will triumph. Likewise, renegade academic Justin Murphy has reported a decline in his online courses post-pandemic. But I suspect Murphy has (as he would put it in his characteristic social science idiom) over-indexed on theorists and philosophers, while I will provide you poets and novelists in a moment when people are rightly sickening of ideology. Also, if I heard right, he gives an annual income of $100,000 from his business as evidence of its decline, whereas I would be over the moon if I made half—even a quarter—of that. (Though in 2023, my first year monetizing, Substack paid about a quarter of my yearly rent, which is hardly nothing—Minneapolis rent, mind you, not New York.) I intend this to be a one-man operation, but I’d also like to feature guests from time to time. I haven’t proposed it to anybody behind the scenes yet, but many friends of this blog are poets, for example, and it might be nice to get their input, considering the volume of poetry we’ll be reading. I’m sure my erstwhile pod co-host, Grand Hotel Abyss’s resident super-patriot, will make an appearance or two, especially when we get to American literature. If you want to come on, please email me at the address in my bio. If not, I might invite you anyway.

I would also like to offer a communal element for the true collegiate experience—or a private network for the true invisible collegiate experience. The posts will have comments sections, but I’m also considering a group chat of some sort on Discord or Telegram. I’ve never done this before, however, so I will have to learn as I go. I welcome your thoughts on this subject—platform preference, advice, etc.—either via email or in the comments section to this post. Paid subscribers will, in any case, receive access to any such forum I set up.

The much-decried “lit bro,” for example, may neglect the importance of this work to his favorite books. Wordsworth is quoted on the first page of Blood Meridian, just as that novel’s title may come from Byron, for example, while the saga of Byron the Bulb in Gravity’s Rainbow reflects profoundly on the legacy of Romanticism. I’ve also written much in these pages about the cult and occult comics of Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison, because, whatever you think of their works in themselves, they have had an enormous subterranean influence on popular culture and counterculture from Nolan’s Batman to True Detective and beyond. These writers are completely steeped in Blake, Shelley, Keats, Yeats, and Joyce, to a degree we haven’t sufficiently recognized.

“Relevance” is not the sole criterion of whether a past work merits study. An over-emphasis on “relevance” encourages a vulgar and presentist attitude toward art the beauty of which should be its own justification, even as this art gives us not a mirror to our obsessions but a window onto otherness. I will dwell on such beauty and such otherness in the course of my lectures. I confess, however, that I’m not much of an antiquarian and share Goethe’s feeling, as quoted in Nietzsche’s “On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life,” “I hate everything that merely instructs me without increasing or directly quickening my activity,” the relevant activity in this case being life in the fractious present.

I also look forward to dispelling certain widespread misconceptions about these writers. To give just one example, you may have heard that British and American Romantics loved nature, and some of them (Wordsworth, Keats) no doubt did, but the details are more complicated: “Where man is not nature is barren” (Blake); “Nature is hard to be overcome, but she must be overcome” (Thoreau).

We’ll also read Joyce’s story cycle, Dubliners, and his autobiographical Künstlerroman, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, since these furnish necessary background to Ulysses. A passing familiarity with Homer’s Odyssey and Shakespeare’s Hamlet is also recommended for readers of Ulysses. Your high-school memories, perhaps refreshed by Wikipedia, are probably adequate to the task.

As readers of my syllabi will note, in this first year of The Invisible College I am partly bringing online versions of two survey courses I used to teach at the University of Minnesota, the aforementioned Brit Lit II and American Lit I. Left to my own devices here on Substack, however, I am doing it my way: teaching the long books I couldn’t fit into a 15-week university course—Moby-Dick, Middlemarch, and Ulysses—and not bothering to pretend I care about 17th- and 18th-century American literature, which has its minor pleasures, to be sure, as in The Coquette and Letters from an American Farmer and the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin and Wieland and the poetry of Anne Bradstreet and Phillis Wheatley and the sermons of Jonathan Edwards and the stories of Washington Irving, but nothing compared to what begins in the 1830s.

If my Invisible College treatment of American modernism seems excessively “white male,” it is only so I don’t repeat myself. Please see my YouTube channel for 20 remote-learning-era lectures originally given for a University of Minnesota course called Introduction to U.S. Multicultural Literatures. Given the institutional mandate of that course to prioritize diversity, I eschewed the likes of Hemingway and Stevens in studying American modernism and focused instead on Gertrude Stein, Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Robert Hayden, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard E. Kim, and more.

So excited for this! Blake has been on my mind, a strong augury!

Excellent New Years’ news. Looking forward to it.