In addition to my regular Friday book review and Sunday weekly newsletter, I am introducing a Wednesday post for Fall 2022. Wednesday posts will contain the creative writing I’ve published elsewhere, whether in a now unused Medium account or in literary journals that have either vanished or that paywalled my work years ago.

[“Iconoclasm” first appeared in the now-defunct Harpoon Review in 2015. As a flash fiction or prose-poem, it is a variation on theme treated with greater complexity in my novel Portraits and Ashes. I am drawn again and again to images of destruction, violence, sex, death, excess of every kind, occurring incongruously in museums and libraries—that tension between the custodial institutions of culture and the culture-producing energies that cultural institutions struggle to contain. I present the story below in unexpurgated form. The third sentence of the fourth paragraph proved too much for the editor who published the story; presumably, the adverbs “sluttishly” and “barbarously” gave gendered and racial offense, respectively, though unmistakably rendered in free indirect discourse, i.e., as the thought of the collective character of my fictional army, not my own thought. I resurface the story today in light of last week’s activist attack on van Gogh. I wrote it near the end of ISIS’s notoriety, and that was probably what I had in mind, but it works just as well as a commentary on today’s progressivist ideology. In retrospect, the 21st century symbolically began when the Taliban blew up the Bamiyan Buddhas. We live in the ongoing shockwave of the epochally iconoclastic act.]

Iconoclasm

In the course of the capture of the city, the army took the museum.

An unofficial force sponsored by no state, assembled from here and there, with this or that equipage, they wore various dress and carried various weaponry. They marked the white floors with the treads of heavy boots or else the prints of makeshift car-tire sandals. Some spat tobacco in brown streaks across the white walls.

What was valuable they stuffed into canvas sacks or plastic grocery bags or pouches they made from their shirtfronts: brooches from ancient Eire, lacquerware of old Japan, the Age of Reason’s tea service. As destructive pleasure is its own value, they sent Ming vases and Aztec terracottas across the tile in scattering shards. It took five men, drugged only with excitement (all other intoxicants being forbidden by their zeal), to push over a plaster replica of Notre Dame’s facade, twenty feet tall. It decorously veiled its own disintegration in a cloud of gritty powder. The men laughed and coughed in the particulate haze.

To God alone belonged the glory, so they targeted representations of the human form in particular for destruction—sensuous idols leading men away from God’s bright but narrow path into the dim maze of desire, an enormous labyrinth where automata solicited attention by mimic-mocking the image of the Lord. True pleasure was communion with the bodiless ideal that God was; all else substituted the false for the true, the representation for the thing, the flesh for the spirit. With bayonets they stabbed the faces from canvases; paintings looked out agape on the massacre of the idols, their centers knifed out. One man with a machine gun mowed down a line of sluttishly bare-breasted Roman goddesses and then a row of barbarously leering Mexican deities; then he assassinated a foolishly smiling Buddha, his hand upraised, counseling peace. An anti-matériel rifle was required to put a bullet in the head of Rodin’s nude bronze Balzac; the man who pulled the trigger fell back from the recoil, cackling. A girl in marble lay prone, her bare bottom and the soles of her feet upturned insultingly at the invaders; they took her to pieces with hammers.

Billows of dust, composed of marble and clay and canvas and plaster and graphite and jade and lapis lazuli, rolled across the white floors.

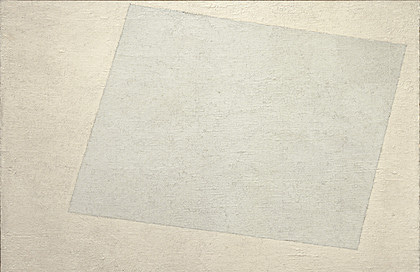

Then a captain halted the army’s progress before a white canvas. Behind his upraised rifle, his men clamored, shouting their judgments.

“This is the frivolity of the unbeliever.”

“They make nothing, literally nothing, and then they honor it in this house. They worship nothing.”

“This is their decadence, this is what we come to destroy.”

“They are empty, and this is their emptiness.”

“With these frauds, they oppress the people.”

The captain mused a while into the swirls of white paint, the impasto blank but for the shadows cast by its own frozen ripples.

“No,” he said finally. “To make an image of God is to blaspheme. But this man has made no image, reserving creation for the Lord.” He indicated the tag to the side of the painting that named the artist and said, “This man is with us. Leave this canvas. Make all the canvases like this. When all the canvases are blank and white as the walls, then we may worship here.”

The men dispersed to hammer stone women into soot, to claw away the faces of popes and burghers.

The captain remained before the painting, his gaze adrift on its empty ocean, his mind at work on the riddle that this rabble behind him had not even recognized as a riddle: nothing was everything, and therefore nothing held the perfection of God. Ensnared by this paradox, the captain fell still and abandoned the violent motions of war. He stared and stared at the painting until one of his men approached him from behind with a service revolver and smeared his fey brain, idolator of nothing, redly onto the blank canvas.