A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Welcome, new and returning readers! You have about 12 more hours to buy yourself a print or Kindle edition of my new novel Major Arcana before it goes into a nine-months’ gestation, only to be reborn as a beautiful Belt Publishing edition in April 2025. It’s been read on French beaches and at bath time by readers who have emerged to call it “humanizing” and “important.”1 You could also offer a paid subscription read the novel’s first and roughest DIY punk serialized version, also including an audio version of each chapter; this will remain available forever. Please read and review Major Arcana today!

A paid subscription also grants you access to the increasingly formidable archives of The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. We have already covered modern British literature from Blake to Beckett in 19 two-to-three-hour episodes, and we are currently in the midst of a summer reading of Joyce’s Ulysses. This week’s three-hour episode, “Always Meeting Ourselves,” is one of the most intense I’ve done, centered as it is on Joyce’s fierce confrontation with Shakespeare and my own fierce confrontation with the Shakespeare authorship question.2 In the coming weeks, we will finish Ulysses, read Middlemarch, and then turn to a survey of American literature from Emerson and Poe to Stevens and Faulkner, encompassing the whole of Moby-Dick along the way.

For this week, two related and disorderly ruminations, each in its way on the metaphysics of fiction: one on the religion of literature and one on what I call “visionary fiction.”

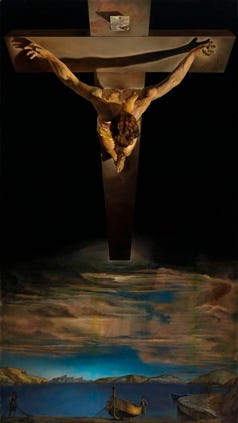

Christ and Anti-Christ (Redux): What Religion Is Literature?

A key theme in these Weekly Readings of last year, written when I was in the throes of Major Arcana, was some potential synthesis of Christ and Nietzsche, by which I ultimately meant to say something “ethics and aesthetics.”3 Life cannot be lived except between and among contradictions, so this synthesis will take place, is even now taking place and has taken place before, whether we conceptualize it or not. Whatever may have divided them, Christ and Nietzsche shared a dim view of the merely conceptual.

This week, the topic rose again, so to speak, when on Monday Naomi Kanakia dropped a Substack post arguing (in the admirably fraught and innerly disputatious third person) that the Gospels are the only living classic among the Great Books—

But, mostly, the Gospels are powerful because their core message is both simple and yet unbelievable: "The first shall become last." The Gospels repeatedly state that the absolute lowest and worst—women, slaves, unclean people, the demon-possessed, tax collectors, etc—will, in the afterlife, be raised above their superiors. It's a simple, compelling, and kinda mind-boggling idea. How can that be true? The reader deeply, deeply wants it to be true, but there is simply no way to make it work out logically. There is no real reason why the least should become greatest.

—just as Blake Smith released an essay in Tablet on Fran Lebowitz that made rather the opposite point:

Middlebrow dullards are suspiciously comfortable with the idea that everyone is morally deficient and that everyone is being criticized by their preferred comedian or prophet. It’s preferable to be told that we’re all born guilty than to hear that you specifically are boring. Thus the enduring appeal of Christianity and its secular successor, socialism—religions that tell us everyone is a helplessly wretched failure needing permanent care from a class of spiritual-political nursemaids, while excusing us from the difficult pleasure of being an interesting person.

Christianity and socialism, being as they are for total losers, posit no moral obligation to be interesting, but we aesthetes very much do. What’s the answer, if we need one? (We seem to need one.) Though she is no friend of Blake Smith’s, La Regina herself, in her magnum opus, writes,

Blood, torture, ecstasy, and tears. Its lurid sensationalism makes Italian Catholicism the emotionally most complete cosmology in religious history. Italy added pagan sex and violence to the ascetic Palestinian creed.

Attractive as that is to certain sensibilities, not excluding my own lurid one, I have long suggested that the best conceptual synthesis of Christ and Nietzsche is nevertheless probably found in Wilde’s De Profundis, which Paglia scorns as sentimental in her turn, and I quote its relevant passage again:

His morality is all sympathy, just what morality should be. If the only thing that he ever said had been, ‘Her sins are forgiven her because she loved much,’ it would have been worth while dying to have said it. His justice is all poetical justice, exactly what justice should be. The beggar goes to heaven because he has been unhappy. I cannot conceive a better reason for his being sent there. The people who work for an hour in the vineyard in the cool of the evening receive just as much reward as those who have toiled there all day long in the hot sun. Why shouldn’t they? Probably no one deserved anything. Or perhaps they were a different kind of people. Christ had no patience with the dull lifeless mechanical systems that treat people as if they were things, and so treat everybody alike: for him there were no laws: there were exceptions merely, as if anybody, or anything, for that matter, was like aught else in the world!

That which is the very keynote of romantic art was to him the proper basis of natural life. He saw no other basis. And when they brought him one, taken in the very act of sin and showed him her sentence written in the law, and asked him what was to be done, he wrote with his finger on the ground as though he did not hear them, and finally, when they pressed him again, looked up and said, ‘Let him of you who has never sinned be the first to throw the stone at her.’ It was worth while living to have said that.

A morality that is all sympathy universally understands, understands almost intransitively, and universal understanding teaches gentleness: not as an ethic but as an aesthetic. Thus our synthesis, whose artistic summa itself is the New Testament to Wilde’s Old: nothing other than Joyce’s Ulysses.

All this Christ/Anti-Christ discourse last Monday followed last Sunday’s brilliant Weekly Weil essay from Mary Jane Eyre literally charting in four quadrants our possible attitudes toward the metaphysical, ethical, aesthetic, and political between the extremes of shallow/deep and cynicism/romanticism. Mary’s post is under the sign of Simone Weil, who understood the historical referents rather differently: like Nietzsche, she reserved her highest acclaim for the Greeks, though for her they were not the original singers of strength but rather the devisers of just the kind of absolute sympathy Wilde attributes to Christ. Weil meanwhile scorned Romans and Jews alike as deficient in this universalism: the first mere imperialists and the second mere nationalists. In his rather patronizing essay on Iris Murdoch in Genius, Harold Bloom curtly dismissed Weil as a pathological case whose vaunted ethics were little better than a bathetically introjected anti-Semitism. There’s probably something to that. I myself favor the synthesizing cultural imagination shown, again, by Joyce in writing a total book at once Greek, Jewish, and Roman, just as it is at once English and Irish.

This is more a set of notes than an essay, and so I note that, just as I was finishing it, another generous review of Major Arcana came in, this time by the aforementioned Julianne Werlin, who compares it to Naomi Kanakia’s The Default World, which I myself reviewed here. I quote her two questions or reservations about my novel:

It really feels like modernism is the aesthetic horizon here. Yes, Blake and Shakespeare are important and the novel (as you’d expect if you’re a reader of Grand Hotel Abyss) is beautifully and capaciously allusive. But it feels like the deeper literary past is itself glimpsed through the decontextualizing modernist lens. That seems true to where culture is at now. But modernism derived so much of its own energy from the collision and reinterpretation of cultural traditions that had been thought to be coextensive with human history. We don’t have that. Is there a way of reforming the relationship between culture and human life without a deeper historical sense? Or does it not matter?

Catholicism. It’s a very Catholic novel. I can see the conceptual fit: birth and death, the word made flesh, transubstantiation, etc. But I wasn’t sure if this is meant to be one potential ideology among others for the novel’s aesthetics or if this is THE framework, without which the whole enterprise loses coherence.

Much as I thank my younger readers for sometimes over-rating my erudition, it’s refreshing to be read by a real scholar (I am not one) who can see clear to the fairly proximate bourne of what I know. I think Fredric Jameson said somewhere that the modernists are for us what the Greeks were for the Italian Renaissance.4 Anyway, Dr. Werlin’s second question would answer her first if only it was an answer and not just another of my own questions. I read these questions and think, “I’d like to know, too!” I am merely the book’s author, not its (or an) oracle, so I will have to remain silent and allow other readers to think through.

All I can say is that I tried, in the single person of Ash del Greco,5 who saw to the end of everything, to accomplish a genuine synthesis of all our civilization’s warring credos—and that Ash del Greco is not so much a literary character I created as someone who came straight up out of the spiraling void and demanded that I tell her story.6

I Have Had My Vision (Redux): What Is Visionary Fiction?

Following my recent review of Emmalea Russo’s forthcoming Vivienne (another very Catholic novel, if I may say), I was asked what I meant by the term “visionary fiction” with which I hailed Russo’s achievement. Considering my admission above that my own characters walk by night, I had probably better answer this question. Please bear in mind that Russo is well-read in the medieval mystics, whereas I don’t know Marguerite of Porete from Chappell Roan, so I can’t place my term in that particular and no doubt relevant lineage.7

By “visionary fiction” I mean fiction that neither rests in a mimesis of what’s merely given in our world nor flies off to some other world, some mere fantasy creation. These are the poles of literature defined by Joyce when he positioned Defoe at one extreme and Blake at the other—except that Defoe at his best is still telling fairy tales and Blake at his best still wrestling with flesh and death.

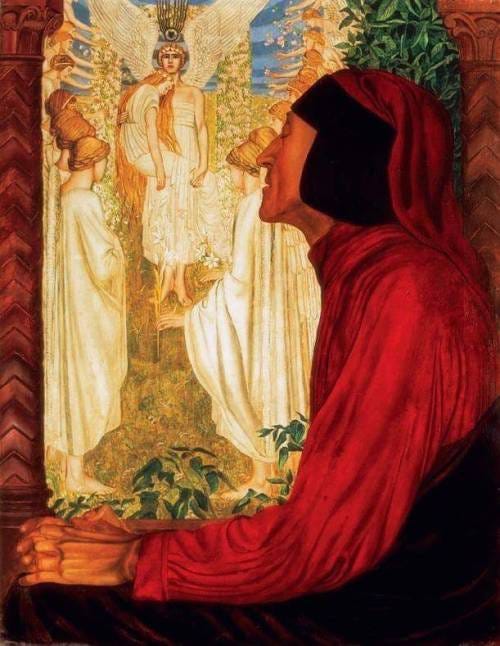

Visionary fiction transfigures the real. It’s what we’re missing in our orgy of autofiction on the one hand and “genre fiction” on the other, the one too real and the other not real enough. This transfiguration of the real is, as I somewhere said of magical realism, narrative in its resting state, what comes most natural to narrative and its narrators, what we find in Homer and the Bible and the fairy tales. I think of the Russian fairy tale that contains the sentence, “The devil came out from behind the stove.” But then Athena grips Achilles’s hair in the heat and dust of battle, and God eats with Abraham in the shade of the tree. Russo’s beloved Dante raising Beatrice to the court of heaven is perhaps our literature’s most audacious example, but Shakespeare’s “bubbles of earth” and ghosts stalking out of Purgatory are further examples.

In modern literature, I find the visionary in the romance tradition: in Mary Shelley and the Brontë sisters, in Hawthorne and Melville, and wittily guised as drawing-room comedy, like Athena disguised as Mentes in The Odyssey, in the novels of Henry James. James but not (I think) Wharton. Dostoevsky with his dream-like intensity—but usually not Tolstoy with his wisdom of earth. The philosophical George Eliot—but usually not the sociable Austen. The 20th century gives us Kafka and Borges, but also the Mann of Death in Venice and Doctor Faustus, not to mention Woolf (whose characters can read each other’s minds) and Faulkner (who sets the Bible in Mississippi). Lawrence and Forster, but probably not Waugh and Isherwood. Kazuo Ishiguro but not Ian McEwan—and not, despite appearances, Angela Carter either, who came to dispel our visions. But, yes, I admit: Nabokov, who rightly described even the most realistic novels as “fairy tales.” Bulgakov, too, and probably Proust. The aforementioned Iris Murdoch didn’t want to write visionary fiction, but she did; Toni Morrison, by contrast, knew just what she was doing. Cormac McCarthy said he was a materialist with practically his dying breath; I ask you not to believe it. Joyce used the “mythic method,” while Ellison spoke of “dilated realism.” Bellow’s were and remain cities (where they are not veldts) of the soul, and DeLillo saw and sees apparitions and apocalypses. They are visionaries all. (Not Roth, though. Even when he fantasized, he, like Tolstoy or Wharton, never left the ground.) Cynthia Ozick, picking Murdoch’s same quarrel with magic except from the viewpoint of the Torah rather than of The Republic, nevertheless rivaled the doomed fantasist Bruno Schulz for visionary energy, not least in her stunning Schulzian novella, The Messiah of Stockholm.8 I invite you to extend the list in the comments; I am probably forgetting someone very obvious.

Whether the 21st century will be a visionary century, it’s too soon to tell—except, I assume, for those who can read the very stars.

These facts led me to reflect on the strangely large number of crucial scenes in the novel that take place either on beaches or in bathtubs, from Marco Cohen’s youthful hallucination to Simon Magnus’s drug-induced vision, from the shared adolescent amours fous of Diane and Ash del Greco occurring in a richer girlfriend’s or theyfriend’s nicer bathtubs (one is “a sunken tub in Carerra marble”) to Diane del Greco and Ellen Chandler’s maternal immersion in the Pacific at the novel’s dead center. There’s even a scene on a French beach:

In December, Simon Magnus had Nice to SimonMagnusself. The streets were empty of tourists; rooms in fine hotels with plush carpets and soaking tubs and balconies overlooking the city were a third of the in-season price. The gray beach stretched into the gray ocean; the gray ocean itself extended to the gray skyline. That was where Simon Magnus spent Christmas, where Simon Magnus welcomed the New Year, only the third of the new century, the new millennium.

Some have credited me with vatic powers. With my characteristic modesty, I disclaim any such acclamation. I notice, however, that I recorded that episode on Thursday night in lieu of watching the Presidential debate, because I thought the debate would be unendurable in one way or another. I was, therefore, delivering the episode’s intemperate tirade about how the deep state rules America and about how “the king is a thing…of nothing” even as we received the most startling and graphic demonstration ever seen in my lifetime that the popularly elected executive does not govern this country. Shakespeare still probably wrote Shakespeare, though, the most recent Art of Darkness podcast episode notwithstanding, as I have argued at length here and here. But I am increasingly charmed by the idea that the original Invisible College and all its Rosicrucians faked Marlowe’s death: is the Satanic poet of Faustus also the poet of Hamlet, this to augment the empire of liberty and individualism that would conquer a quarter of the planet only to be denounced by Stephen Dedalus in the phrase, “Khaki Hamlets don’t hesitate to shoot”?

I see on social media that we’re doing Lolita discourse again, for the umpteenth time in the last decade. This novel has become our ultimate touchstone for the ethics-and-aesthetics question. That’s too bad, because Nabokov’s tedious gamesmanship invites the kind of moral binarisms the novel now attracts. This is itself, I have long assumed, part of the wicked amoralist mandarin author’s hoax on his benighted readership. Anyway, this round was touched off when a controversial bestselling author described the novel as a “love story” to a large public outcry. But her description is only a problem if you think that “love story” is an automatic honorific or that love is never hurtful or perverse or awful. A distinguished critic proposed, conversely, that the novel is a “moral test.” I am myself a sufficiently amoralist author to think the place for a novel that is a “moral test” is the trashcan. Anyway, because Lolita has attained this status, I’ve written a lot about it in the last decade. Here is my formal essay from 2018, written after I taught the book to an introductory literature class at the outset of #MeToo. (That class turned out to be full of high-school girls taking it for college credit—I didn’t know this when I designed the syllabus!—and they absolutely loved the book, for whatever it’s worth, and wrote papers about Nabokov and Lana Del Rey with titles like “Lolita is Not #Goals.”) Here is a one-paragraph version of my perhaps excessively contrarian reading of the novel, posted a year or two ago to Tumblr, which I think condenses my view of the matter most concisely:

Martin Amis wrote an essay about 15 years ago where he conceded that the master probably did have a thing for 12-year-old girls considering the frequency with which they appear, pantingly described, across his oeuvre. I’ve long suspected this has to be final turn of the screw in interpreting Lolita. If Humbert is not renouncing something real, a desire depicted as metaphysically authentic irrespective of morals, then the novel is without emotional ballast or philosophical point. It’s only about a pathological case, the very possibility mocked and dismissed in the preface. But when we allow that the book legitimates Humbert’s desire if not its fulfillment, largely through the eroticism of its prose, we undermine the already shaky case for the Kantian moral therapy it is supposed to administer according to Richard Rorty and others, as if the only point were to treat others with kindness, a recommendation that may be made without either the mythical apparatus of nymphetology or the aestheticization of pornography. Lolita really is closer to certain Platonic gay novels, not only Death in Venice but also Billy Budd and Dorian Gray; these don’t shy from implicating their authors in the forbidden desire the authors’ gaze transmits in the very course of narratively surrendering, this to elevate art over eros. An unspoken and unspeakable consensus about the differing natures of male and female sexuality irrespective of gay/straight, as well as Greco-Roman aesthetic precedent, leads us to tolerate the scenario more when the object of desire—real desire, thus painful to be renounced even if it must be renounced, as in the Phaedrus—is a boy rather than a girl. Hence we squeamishly deny what Lolita is actually about, missing both the true nature and the true cost of its greatness. My uncharacteristically moralistic hope is that we have progressed past the point where we need to illustrate this philosophical thesis with this subject matter.

See also friend-of-the-blog Alice Gribbin’s appearance on the Manifesto! podcast to discuss Ezra Pound, which much good-natured dispute over Pound’s relation to Romanticism and his scientific pretensions. I look forward to investigating this matter more closely in the fall on the scheduled Pound episode of The Invisible College. My admittedly incomplete understanding, derived from Pound scholar Leon Surette’s study The Birth of Modernism: Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, W.B. Yeats, and the Occult, is this: Pound believed himself to be perpetuating a secret goddess-worshiping magical tradition running from the Eleusinian Mysteries through the Troubadours and Dante to the Romantics, of which the high modernists were the final heirs. The role of mariolatry in specific and of sensuality in general in even official Catholicism, whose central poet is on this theory actually a gnostic Troubadour worshiping the girl next door as his personal patron goddess, makes it mainstream religion’s most reliable outlet for this occulted tradition of universal word-made-flesh. Or so the conspiracy theorists say.

In Udith Dematagoda’s brilliant new essay on the figure of the egirl I selfishly find a gloss on Major Arcana’s story of Ash del Greco and Jacob Morrow:

A frequently mistaken critique of the male psyche holds that what men truly desire is a beautiful, silent, compliant, and dutiful woman. I have yet to meet any man who seriously entertained such notions. On the contrary, I have known countless men, myself included, who have been hopelessly in love with vociferous, strong-willed women who lead chaotic lives eliciting their sympathy and desire to protect; women capable of great cruelty but equally of intense devotion which, most importantly perhaps, is freely given.

Major Arcana remains the only text in existence to use the phrase the zeitgeist demands: “Et in Arcadia Egirl.” For more egirls, see also my recent review of Dematagoda’s new novel Agonist.

Somewhere in Strong Opinions, Nabokov said of Forster’s line about how his characters would get away from him:

My knowledge of Mr. Forster’s works is limited to one novel which I dislike; and anyway it was not he who fathered that trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is as old as the quills, although of course one sympathizes with his people if they try to wriggle out of that trip to India or whereever he takes them. My characters are galley slaves.

By contrast, I quote Toni Morrison in conversation with Gloria Naylor in 1985, discussing the metaphysical reality of their characters:

GN: A lot of people don’t think that our characters become tangible to us.

TM: Some people are embarrassed about it; they both fear and distrust it also; they don’t solidify and recreate the means by which one enters into that place where those people are. I think the more black women write, the more easily one will be able to talk about these things. Because I have almost never found anyone whose work I respected or who took their work that seriously, who did not talk in the vocabulary that you and I are using; it’s not the vocabulary of literary criticism.

GN: No, it’s not. (qtd. in Conversations with Toni Morrison)

The term is already in use, according to Wikipedia, for books like The Celestine Prophecy and The Alchemist, but this is not what I mean either, though it’s not unrelated, except as a matter of literary quality, to what I do mean.

Mary Jane Eyre’s aforementioned chart and this question of visionary fiction reminds me of the chart of schizo/sacramental and autistic/gnostic temperaments from this old Weekly Reading post. I discovered the chart online two years ago and immediately began using it to plot the sensibilities of many major writers. I immodestly even used it to analyze myself—though not our veritable age of taxonomies.

If I may, I think Hart Crane gives us a hint towards what visionary literature looks like that is quite similar to your definition when he specifies that "the visionary company" is one of "love" in "The Broken Tower." Love here meaning something both like the Shelleyan platonic ideal of love as the true unity of all souls in friendship and brotherhood and in its earthly, sensuous form as the poet's vision must "dip / The matrix of the heart" to "lift down the eye / That shrines the quiet lake and swells a tower." Crane ends with the further reconciliation of our two poles (romantic and realistic, Blake and Defoe, heaven and earth) as he sees the visionary heights of the sky finding its purpose in "Unseal[ing] her earth" and "lift[ing] love in its shower" which I take to mean as the sky makes the earth beautiful as it is, or, as you might say, the sky's showers of love transfigure the real of the earth into the beautiful and the strange (the shower image btw comes from a tercet of who else but Dante in Canto 14 of Paradiso). Furthermore, I find Crane's "crystal Word" similar to Pater's "hard, gemlike flame" the paradox of which you've emphasized before and which I assume is more or less the goal of visionary fiction: to take the singular beauty of what one sees arising beyond reality but is always fleeting and arrest it in reality.

To try and connect the two sections of your post, is love, in its visionary mode, not also the avenue of sympathetic imagination that you, myself, and Wilde all find so aesthetically interesting in the figure of Christ? The synthesis with Nietzsche being that the sympathetic internalization of the other (paradoxically?) announces the other's individuation and so everyone is an exception and unique while also still to be found within each individual (I'm also thinking, parochially perhaps, of Keats's interdependent concepts of negative capability and self-concentration). I may be off the mark here, but the whole process reminds me of Bloom's comments on Wordsworth's love of nature where "internalization and estrangement are humanely one and the same process."

Sorry if I've just mainly repeated what you've said in the post (and for turning to verse and not prose), but I'm also trying to work through some of these concepts for some projects I'm thinking through right now. There's also the very real possibility I've butchered your thoughts entirely lol and if so apologies to the maestro.

Regarding the comment about "Major Arcana" as a Catholic novel - yes, there's a lot of Catholicism in it, but I think the true religious feeling in the book is aesthetic, i.e. religious devotion transmuted into art as a religion. And then the Ash del Greco storyline goes even beyond this, into dizzying metaphysical realms. This also, I think, accounts for the somewhat "old-fashioned" vibe I get from the story - despite being technologically very up to date, the characters and their quests seem like something from the Romantic era or even older.

I noticed that another of your reviewers said something along the lines of "it makes the present seem so remote and far away," and I definitely got the same feeling from it.