As promised, I will occasionally post brief reviews of new and forthcoming books sent to me in exchange for an honest response. The book reviewed below will be released on September 10 and should be preordered here. Please enjoy!

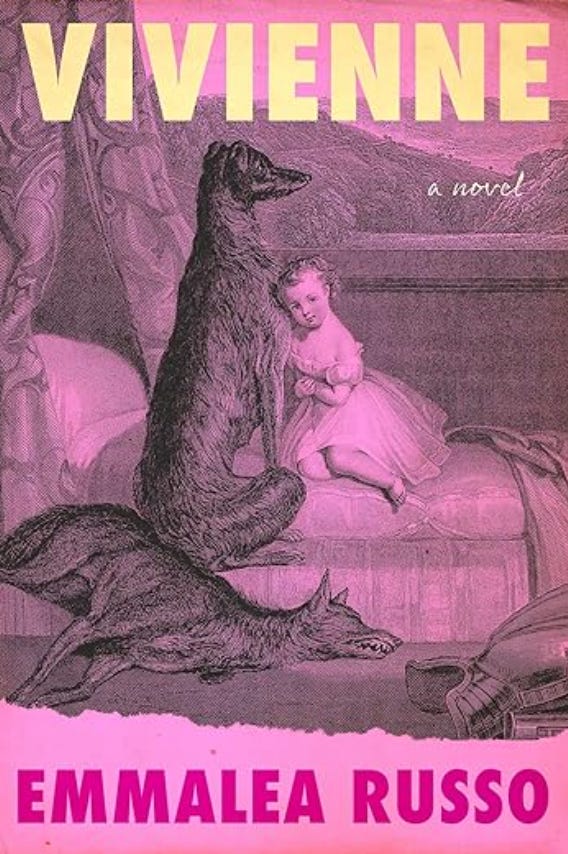

Emmalea Russo, Vivienne (Arcade, 2024)

If the origin of my work is scandalous, it is because for me, the world is a scandal.

—Hans BellmerThe German-born artist Hans Bellmer began making and photographing his famous series of adolescent female dolls in the first year of Hitler’s reign. The dolls’ eerie and uncanny disarrangements around Bellmer’s ball joint are often read as his protest against personal and public patriarchal politics: the cruel reign of the father in the home and of the Führer in the homeland. On the other hand, Bellmer’s feminist exegete Therese Lichtenstein, applying psychoanalytic theory for a less salubrious reading of the obsessive gesture in her 2001 study of the artist, writes as well of his “deep narcissistic identification” with the female adolescents the sometime transvestite artist portrayed. One of the first publications of his doll photos appeared in the Surrealist journal Minotaure in 1935 with the subtitle, “Variations sur le montage d’une mineure articulée.” The writer and artist Unica Zürn became Bellmer’s companion in his later life until her suicide-by-defenestration in 1970 at the age of 54.

The above is all you need to know to enjoy poet Emmalea Russo’s deliriously beautiful debut novel Vivienne, forthcoming in September. In Russo’s story, the fictional title character, Vivienne Volker, was Bellmer’s final lover and collaborator. Vivienne is an artist in her own right best known for designing clothes for the artist’s dolls, clothes that rival their “wearers” for provocative interest.

Vivienne is set mostly over the course of one week in December in the present day. It begins when Volker is selected to have her work exhibited in a feminist gallery show of “forgotten women Surrealists” only to find her appearance and her person canceled by a consortium of concerned artists, academics, and activists operating as the “Coalition for Artistic Harm Reduction” or “CAHR.”1 While their case against Volker centers on her alleged complicity in the window-suicide of Bellmer’s previous lover Wilma Lang (also fictional), their list of her works’ artistic transgressions—“Abortion / Amputation / Anxiety / Animal abuse” etc.—illustrates a 21st-century climate of cultural fear obviously inimical to avant-garde art of any sort.2

While the novel begins with a chorus of social-media voices immersing us in these contemporary cultural politics, and while this chorus in Russo’s expert imitation of our era’s ever-present online hum and buzz recurs at intervals throughout the text in both comic and lyric counterpoint to the main tale, Russo soon enough surpasses satire and brings us into the novel’s true hearth and home: the rural Pennsylvania retreat where the octogenarian Vivienne lives with her (and Bellmer’s) middle-aged widowed daughter Velour and Velour’s own daughter, the seven-year-old Vesta Furio, not to mention Vivienne’s much younger3 garbage-man lover and the family’s beloved dog, Franz Kline.

Let’s admit up front that we expect a poet’s first novel to satisfy on the style front. Russo certainly does, as when she provides Vivienne’s Surrealist prose-poetic accompaniment to her own artwork:

In the silver river, I’m a pony. Clothesless and roaming. Precisely when you run your finger over the stitches. Bound bone and tremendous ditches are shocked as they clock your helmet and black trench coat. You were a loaded Giotto.

But let’s confess as well, in the spirit of brutal honesty, that we might also be a bit skeptical of a poet’s novel when it comes to characterization and plotting. Never fear, however, because the admirably larger-than-life Vivienne, Velour, and Vesta4 comprise the most vivid family I’ve encountered in recent fiction: the church-going and vision-seeing high priestess of a grandmother, with her ambivalent memories of avant-garde Paris; the nervous, almost agoraphobic daughter, still grieving the loss of her husband to an overdose even as she devotes herself to her parents’ legacy, a shut-in who spends her days in “her eponymous robe”; and the granddaughter, Vivienne’s own articulate minor, trying her best to be like her brilliant grandmother, to mourn her lost father, to care for her beloved Franz Kline, and to study the Tarot cards mounted on her bedroom wall, which she appreciates not as divination tools but, the narrator tells us, “as art.”5

Despite its serious subject matter and overall air of elegy for its evanescing matriarch, Vivienne is also a very funny novel. The family’s inner exchanges are convincingly comic—

—I had a terrible dream, Vivienne declares, sitting down at the table.

—Me too! Vesta yells.

—What was yours, mon cherie?

—A dog hanging from a tree.

—Like in that movie.

—What movie? Velour asks.

—The one Nana showed me.

—Which one?

—The Passion of Anna, Vivienne says.

—Mother, why are you showing her Bergman? She’s seven.

—Why not?

—I liked it, Vesta reassures.

—You liked Bergman? Velour says.

—Uh huh.

—It’s so morbid, Velour says to her mother.

Vivienne shrugs, lighting a cigarette.

—What’s morbid?

—Very interested in death, sad and dark stuff, Velour says, exhaling.

—You’re morbid, the child replies.

—Nope.

—Well, in case anyone’s wondering, I don’t remember my dream, Vivienne declares, but I woke up inside a gruesome psychic residue. So I just knew.

Velour rolls her eyes. Vesta blinks up at her grandmother, transfixed.

—I have residue, too, says the girl.

—as are their interactions with their more “normie” rural neighbors, whose own perspective Russo’s motile narrator occasionally inhabits, as for instance when a neighbor with a lost dog consults a disoriented, under-nourished, and menstruating Velour just then wandering her yard in her dirty robe with her own dog and a family of ducks:

As Mac pulls away, he watches Velour float around the yard in her white robe, one duck quacking under her arm as two others trail behind, the dog circling the bonkers flock. He watches as she tosses something into the landscape, which makes him feel queasy and high. Almost happy. Not quite. Velour Bellmer must be, he thinks, the strangest woman he’s ever seen.

Such imagery, at once homely and mythic, comic but also somehow oneiric or hallucinatory, at once animal and divine, ineffably characterizes Vivienne as a whole. It’s the rare type of novel you could both mistake for your own life but also have strange dreams about. I am reminded of Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s remark about Wuthering Heights in The Madwoman in the Attic:

[B]ecause it is so prosaic a myth…Wuthering Heights is not in the least portentous or self-consciously “mythic.” On the contrary, like all true rituals and myths, Brontë’s “cuckoo’s tale” turns a practical, casual, humorous face to its audience. For as Lévi-Straus’s observations suggest, true believers gossip by the prayer wheel...

After we’re introduced to the social-media chorus and the to the house of Bellmer-Furio whose rise and fall this chorus observes, the remainder of Vivienne’s tragicomedy narrates in an absorbingly sensory and subjectivizing third-person prose the story of how Vivienne’s cancellation—and her attempted un-cancellation by a hip and ambitious New York gallerist with his Rick Owens gear and intermittent fasting routine—upends this fragile family and brings them out of their rural PA fastness, first to the metropole and then eventually, in the novel’s brilliantly unexpected conclusion, to the desert, to the future.

The result is a densely lived-in and suspenseful novel, a novel we can pleasurably inhabit for the duration of the reading. For all its repletion of lyricism and symbolism, I read the 240-page book in two days. (Then I read it again.) Our poet can characterize, then, and our poet can plot. What might it all mean?

First, we detect an implied polemic against the intrusion of excessive public political and moral judgment into the domains of subjectivity, of private relations, of faith— above all of art, whose purpose is to treat experiences that cannot be reduced to binary judgments of good/bad and right/wrong. The point is not exactly to evade politics and morality, but to demonstrate the real difficulties they present in the fullness of experience. Was Vivienne Volker responsible for Wilma Lang’s suicide, either because she pushed her out the window or because she “stole” Bellmer from her? Those who wish to cancel her say a simple “yes,” while she more persuasively tells Vesta, who has significantly accompanied her to church for confession,

I didn’t push her, not literally. But that doesn’t mean I’m not responsible. I’m answerable, in a sense. Not to them, the voices, mechanical…those…people talking. But to Him. To you. Myself. Another power, divine. (ellipses in original)

This perceptive novel, alive to its (if I may) “nonbinary” source in Bellmer’s gender-bending art, also addresses the double standard applied to the female artist—sometimes applied, to be sure, by female audiences—that transgression can be left to wicked men, while women’s art and even women’s lives have to demonstrate care (CAHR). Russo rejects this particular version of the gender binary and picks up instead on a Catholic and occult vein of imagery celebrating a much grander reality of the feminine, both richly earthly and richly spiritual, circumscribing mere social judgment:

After wiping the [period] blood off the bathroom floor, [Velour] examines the gelatinous globs in the toilet, like wet gummy candies. She reaches in and grabs one, presses down and tries to crush it. Holding the dripping specimen, she feels, for an instant, that it’s a piece of art she’d made. She places the clot on her tongue like communion, tastes iron and salt, then opens her mouth and lets it fall back in the toilet.

As for the concept of maternity offered us by this three-generation saga of mothers and daughters, I will leave it to readers to discover, since it depends in part on the extraordinary and unexpected conclusion.

Vivienne is a novel of rare vivacity and invention in a literary period not noted for visionary fictions: a vital recreation of the sheer scandal of our surreally real lives, a poet’s novel in the sense in which all novels worth the name should be poets’ novels: a work of poiesis, the inspired formation or manifestation of a new reality.

Readers, their eyes straying in a nervous tic to the elephant in the room, will of course speculate about the source of this novel in Russo’s own scandal. She addresses her “poetic cancellation” here and here—as well as in an appearance on my podcast about a year ago, where we discussed not only her cancellation but also her poetry; her interest in Tarot, astrology, and alchemy; her literary tastes; and the movie Altered States.

In her concluding “Notes” to the novel, Russo allows that the fictional Vivienne’s work is inspired by Zürn’s real art, though the fictional Wilma (rather than Vivienne) dies Zürn’s death. Compounding her irreverent and audacious reinvention of art history, Russo gives her hip gallerist an accomplice (a friend of Velour’s) whose artist mother was also allegedly pushed out a window by her artist father. (The unspoken reference is likely to Ana Mendieta, though Russo provides her fictional stand-in with a happier ending; the real-life feminist activism around Mendieta’s suspicious death may lurk behind CAHR’s fictional activities.) “[Y]ou both have parents with window drama,” the gallerist dryly comments of her and Velour.

I count four vastly age-gapped romantic relationships in Vivienne, many of them commented upon with judgment and alarm by the novel’s social-media chorus and all of them portrayed by Russo with relative sympathy—perhaps a motif suggesting that the erotic life, like the aesthetic life, is not necessarily best lived according to punitive social roles or in anticipation of categorical social judgments.

I’ve never believed that novelists should pick characters’ names out of the proverbial phone book. The names should both sound good and mean something. When she appeared on my podcast as aforementioned, Russo also cited D. H. Lawrence as a novelistic inspiration. In Lawrence’s “fascist” novel The Plumed Serpent, a character exclaims,

“Ah, the names of the gods! Don’t you think the names are like seeds, so full of magic, of the unexplored magic?”

She also cited Nabokov, a writer as different from Lawrence as one can imagine, who also wrote little lyrics with just a given name and a surname: Dolores Haze, Hazel Shade. I like the suggestiveness and symbolism and alliteration of Vivienne, Velour, and Vesta—the list, like CAHR’s list of Vivienne’s artistic transgressions, a poem in itself.

I’ll leave readers to discover the full six-card spread taped to Vesta’s wall, except to say that, amateur reader as I am, only one card gave me serious interpretive trouble in terms of its place in the novel: the Seven of Swords. Then I recalled the cheerily cynical apothegm of the avant-garde often attributed to my fellow Pittsburgher Andy Warhol but apparently said rather by Marshall McLuhan: “Art is what you can get away with.” It follows that a society in need of real art will have to let real artists get away with a certain number of transgressions, even if God or “[a]nother power, divine” does not. Vengeance, anyway, is God’s, not ours, as the Good Book says.

I'll definitely keep an eye out for this! I read Emmalea's wonderful poetry book "Magenta" which she released for free into the public domain. Definitely a visionary literary artist.

Thanks for connecting the Unica Zurn / Hans Belmer dots. love this novel. Russo's poetry is also kickass.