As promised, I will occasionally post brief reviews of new and forthcoming books sent to me in exchange for an honest response. The book reviewed below will be released on May 31. Please enjoy!

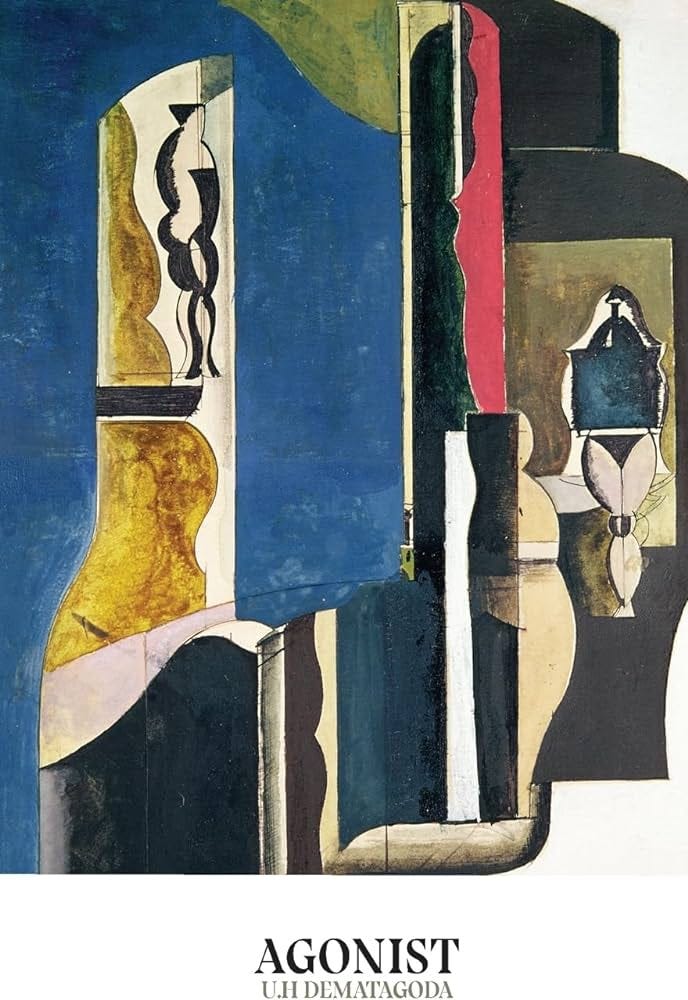

U.H. Dematagoda, Agonist (Hyperidean Press, 2024)

An old cartoon, riffing on a sentimental injunction bizarrely misattributed to Plato, once read: “Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle—on the internet.” This battle—or, as Plato might actually have said, this agon—is the one to which the title of U.H. Dematagoda’s new novel alludes.

Dematagoda is a Scottish scholar of literary modernism who has previously written on Nabokov, Wyndham Lewis (one of whose paintings adorns Agonist’s cover), and “the ideological aesthetic.”1 Agonist is no academic performance, however. Its one-page prelude begins:

It flows underground. Or rather it trickles. And on the surface something lays rotten, snapped off from the golden bough and fallen down through the sacred canopy, now nothing more than a gaping hole a pustulating cunt (a motherless cunt) from which will eventually issue forth nothing but its own analogous reproduction not even silence not even respite.

The golden bough gains pious Aeneas admission to the underworld to see his father’s shade in Virgil, but the underworld in question here, reproducing itself out of itself like a metastatically artificial birth canal, is the infinitude of online discourse, a horrible parody of the mother’s womb where we float in our permanent infancy. Agonist’s seven subsequent sections proceed to dramatize this festering imposthume and consequent arrested development in the language of our time. There is no narrative and no narrator, just a canny reproduction of the timeline, organized poet-wise by rhythm and motif.

Picking up on the prelude’s faux-vaginal imagery of the internet as feminine artifice, the first section is called “Hetarae” (Greek for “courtesans”), and the voices we hear are those of egirls, whose refrain—each section has a refrain—is “…but by hot girls,” e.g., “Abstract painting, but by hot girls,” “The fight for restorative justice, but by hot girls,” etc. These courtesans vending images of their intellectual and erotic appeal in the attention economy give way to a succession of equally dire male voices in the following sections.

The second and third sections are “Nullity” and “Hypertrophy,” in which different styles of right-wing anons do combat in their rudest rhetoric, rhetoric too rude to be quoted here or to be published by any these days but a daring small press like Agonist’s Hyperidean. The section title of “Nullity” is self-explanatory, the ironic (or is it?) refrain, “I’m gay!,” while “Hypertrophy” may refer to the Bronze Age Pervert fandom of body-builders’ exaggerated musculature, or “fizeek,” as they quarrel over race science and the correct interpretation of European culture (refrain: “I’m a Fascist!”).

Dematagoda then turns his attention to the political left. “Il se croit” (i.e., “He believes that he is…”) is where the woke left-libs gather in their self-congratulation to shout “Democracy!” and “Socialism!” and “NATO!” But the subsequent “Contact” is the richest and most novelistic of all the sections—perhaps, I impertinently surmise, because it’s the one where Dematagoda describes his own class and milieu.2 “Contact” is about the downwardly mobile radical intellectual left, though here we get more than the other sections’ artfully recreated Twitter chatter. Agonist almost approaches conventional human interest in a long epistolary exchange between mismatched lovers (a smug young intellectual woman distorted by ideology and a cruelly remote intellectual male she both attempts to seduce and to repulse) and a ranting monologue in Scottish slang by a cynical immigrant’s son attempting to rise in the world:

...wake up late and write the occasional song...write a novel...write poetry...balls deep in the daughters of the bourgeoisie...that’s real democracy!...those are my principles!... the ‘do’ nothing mode...what else am I gonna do?...no jobs out there for a renaissance man these days!...nothing for it... how else you gonnae have hopes of keeping this up!...nothing for it...just got tae stay in uni somehow...become an intellectual...start reading The Guardian...start agreeing with other middle class cunts...that’s how you get ahead...start speaking even more like a fucking poof...so much so that cunts start tae thinking yer English...surrounded yerself wi other try-hard cunts that want to be intellectuals too...soft cunts...delusional cunts: fast-track to being respected type of cunts!... (ellipses in original)

None of the “contact” promised by the section title materializes, but only a dystopian picture of relations between the genders, between the classes, between us and our century.

Finally, “In Order Not to Sleep,” reminding me a bit of DeLillo’s underrated Cosmopolis, drops us into the insomniac and loveless life of a German businessman in London. The codes underwriting the social-media timeline of the earlier sections—and gradually Agonist does seem to move offline, to recreate IRL dialogues and experiences—are based nowhere else but in a real world more or more reduced to loveless flows of capital. A one-page epilogue, “Spirit of Our Depths,” recapitulates the prologue’s imagery of the watery deep.

What to make of this startling, abrasive performance, this new Waste Land of shitposts? Modernism’s strategy was to lift the degraded present into myth and symbol, a Yeatsian artifice of eternity. This is performed in Agonist by its persistent idiom of classical/global language and legend resembling modernist practice: the Chinese character for “void” appears on the title page, beneath the subtitle “Accumulations from the Void,” though Dematagoda is not in the Poundian habit of breaking into Chinese frequently; the section divisions are marked by sigil-like images of rose, mountain, cross, and more; and the letter “O” in various linguistic and diacritical permutations—Ô, Ø, Ö, Õ, Ò, O—presumably a graphical signifier for the prologue’s “gaping hole,” and maybe also a sonic echo of the agonist’s sighing or crying, also appears between sections. This aestheticizing of the void is a way of affirming a life we could not obviously have avoided living anyway. One must make a virtue of necessity; it’s called having a tragic worldview. For all their “panorama of anarchy and futility,” Eliot’s macaronic London and Joyce’s polytropic Dublin, rather like Dante’s lively Inferno and poignant Purgatorio vis-à-vis the stasis of his Paradiso, have an ineffable aesthetic appeal—and so, at its best, does Dematagoda’s accumulated digital dystopia, his “Agon, Agon, Agon, Agony.”

Read this way, Agonist does not merely mock the attention-seeking egirls and resentful incels and bathetically ineffectual neoreactionary and neo-Marxist intellectuals of “online,” nor only gawp in horror at the internet’s spawning maw figured as the hellmouth of a monstrously artificial vulva—neither of these, it seems to me, would be worth doing—but rather maps, and in a form more permanent than the TL, the new mythic terrain where we live out our souls’ ever-more-disembodied destinies. If Wyndham Lewis’s credo was, “Long live the vortex!,” Agonist’s credo—or at least its effect—might be, “Long live the void!”

The latter is too theoretically rigorous for me, but I gather the basic idea, one also animating Agonist, is that digital culture renders the aesthetic the primary category of our age, superseding and subsuming ideology. Even ideologies are aesthetic choices now, costumes chosen for the appearances and affects they afford rather than adopted out of conviction or necessity. I’ve also barely read any Wyndham Lewis beyond the BLAST manifesto material. But, being a simple-minded denizen of “online” myself, I enjoyed this video of our present author discussing the more familiar Conrad on walkabout.

When I say “novelistic,” I have in mind Barthes’s phrase for the experimental writerly text in S/Z: An Essay: “the novelistic without the novel.” The arch-deconstructive Barthes of S/Z, disaggregating a Balzac nouvelle into its component ideological codes, would have loved Agonist, a novel made up almost solely of ideological codes. This is not an avant-garde gesture, however, but a strictly mimetic one, since the social-media world Dematagoda represents consists of little but codes and ideologemes.

exactly type of thing I didn't know I was looking for. great review sir, cheers!

I tend to avoid “Internet novels” like the taxman, but after this review, I might make an exception here.