A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Welcome to the new readers I’ve gained since my appearance this week on Substack Reads, and thanks to Sam Kahn for featuring me there!

A new five-star review of my novel Major Arcana has recently been posted to Goodreads. It says simply, “Just breathtaking! Let it introduce you to some of the most memorable characters you’ll ever encounter.” You too can have your breath taken away in print here, on Kindle here, or in two separate electronic formats—serial with audio posts and pdf—if you are a paid subscriber to this Substack. For more on the novel, see my conversation with Ross Barkan and this spoiler-free but comprehensive review by Mary Jane Eyre. Please contact me at johnppistelli@gmail.com or DM on Substack to inquire about review copies. I will give a free pdf to literally anyone who wants to write a review anywhere; I will send a print copy to anyone who wants to write a review in a prominent publication.

Meanwhile, our spring survey of modern British literature in the Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers, is drawing to its close. This week I posted “Find the Mortal World Enough,” an episode about the life and work of W. H. Auden. His moral sobriety probably keeps him below Yeats and Eliot in the ranking of the great modern poets, but still, we could use our fair share of it today, about which more in a moment.1 Next week, find out if I can learn to love Samuel Beckett in time for an episode on Waiting for Godot. After Beckett’s post- and anti-Joycean non-event comes the event you’ve all been waiting for: a summer luxuriation in Joyce, 20th-century literature’s fabulous artificer himself. If you’re not a paid subscriber yet, you will surely want to be before we embark upon our two-months’ reading of Ulysses.

For today, a B-side of my Auden episode: some quotes about art, politics, and religion from an unknown little book of his that speaks directly to our present moment, with interpolated comments of my own. And don’t miss the footnotes, where I weigh in on a number of trending political controversies and give a (disappointed) review of the trendy new horror film I Saw the TV Glow. Please enjoy!

The Artist vs. the Politician: Auden on “The Prolific and the Devourer”

In my Auden episode of The Invisible College, I mentioned that I’d recently discovered a little book by the poet in the library, The Prolific and the Devourer. It’s a posthumously published work of meditative prose Auden wrote for himself around 1940 as he was making the famous transition from his 1930s leftism to the chastened Christian moderation that would characterize his later life. The second section of the book accordingly develops Auden’s view that Jesus Christ was the greatest of philosophers and reformers, a Freud of antiquity doctoring to neurotic humankind: dispelling hysteria, enlarging sympathy, and making true progress possible by reconciling us to the love we first learned of, however imperfectly, in the nursery.

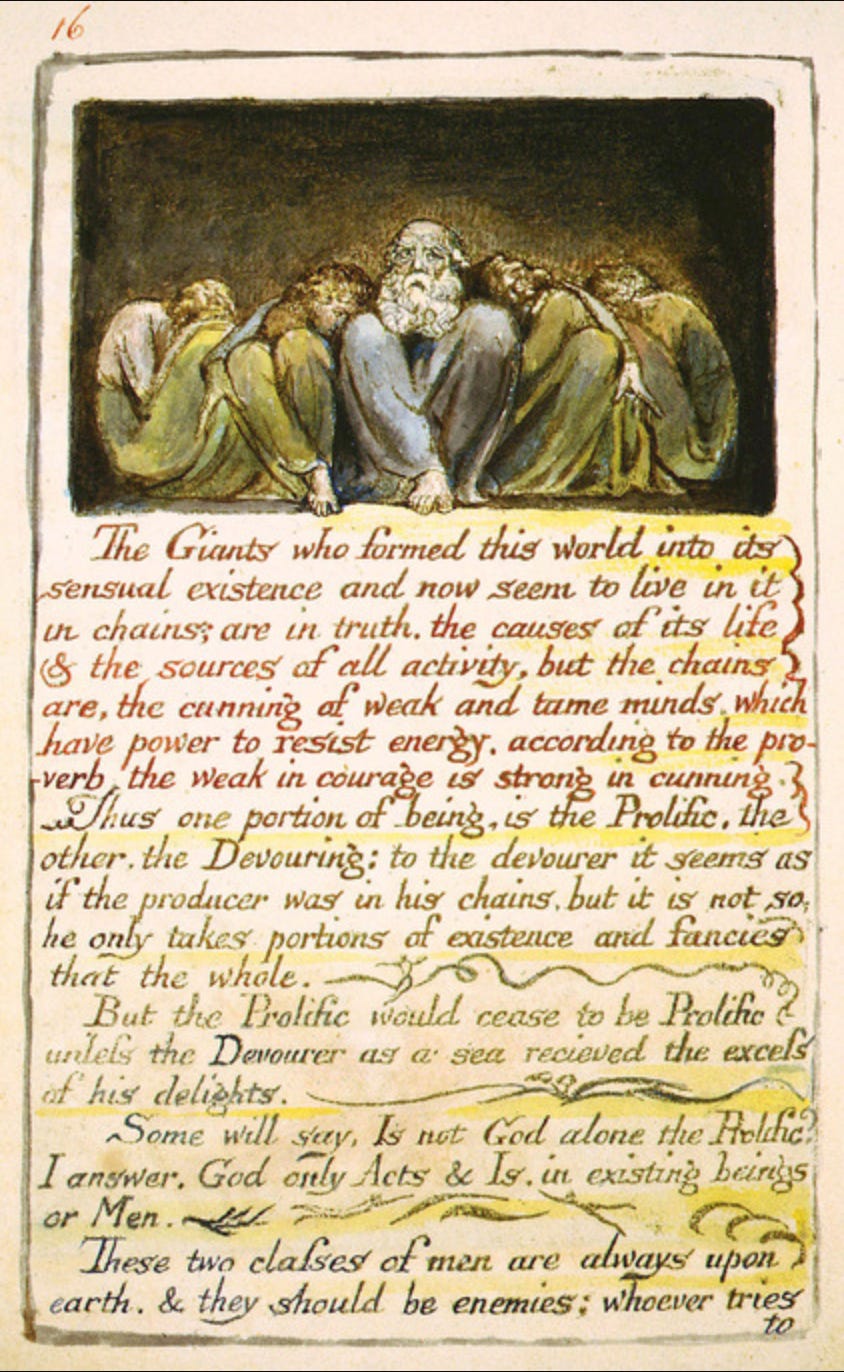

The book’s first section, however, is a collection of aphorisms and meditations I found extremely resonant for our own literary period.2 Since this is an obscure book, I would like to quote some of Auden’s thoughts below with glosses of my own. The title phrase is from The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, for which see my free Blake episode. Blake writes:

The Giants who formed this world into its sensual existence and now seem to live in it in chains are in truth the causes of its life and the sources of all activity, but the chains are the cunning of weak and tame minds, which have power to resist energy, according to the proverb, “The weak in courage is strong in cunning.”

Thus one portion of being is the Prolific, the other the Devouring. To the devourer it seems as if the producer was in his chains; but it is not so, he only takes portions of existence, and fancies that the whole.

But the Prolific would cease to be prolific unless the Devourer as a sea received the excess of his delights.

Some will say, “Is not God alone the Prolific?” I answer: “God only acts and is in existing beings or men.”

These two classes of men are always upon earth, and they should be enemies: whoever tries to reconcile them seeks to destroy existence.

Auden provides his own interpretation of Blake’s opposition:

The Prolific and the Devourer: the Artist and the Politician. Let them realise that they are enemies, i.e., that each has a vision of the world which must remain incomprehensible to the other. But let them also realise that they are both necessary and complementary, and further, that there are good and bad politicians, good and bad artists, and that the good must learn to recognise and to respect the good.

Auden explains that the politician seeks “salvation” through “the manipulation of other men,” whereas the artist seeks it through “the manipulation of his own phantasies.” They will necessarily interfere with each other’s ambitions, then, insofar as politicians at their maximal worst will want to control the “phantasies” of the populace, while artists at their maximal worst will want to inflict their own “phantasies” on everyone.

The artist, he tells us, crisply asserting a point I have myself made at greater length, stands in relation to the politician as the petite bourgeoisie stands in relation to the state:

Works of art are created by individuals working alone. The relation between artist and public is one to which, in spite of every publisher’s trick, laissez-faire economics really applies, for there is neither compulsion nor competition. In consequence artists, like peasant proprietors, are anarchists who hate the Government for whose interference they have no personal cause to see the necessity.

Given the petite bourgeoisie’s bad reputation as “the class that holds back history” in Marxist theory—I have argued more than once that the lower middle class is Marxism’s actual class enemy, not the grand bourgeoisie, which expert-class leftists both envy and wish to usurp—this is a fact about which left-wing artists would prefer to deny. They deny it via their self-regarding, self-flattering, and deluded identification with the proletariat, or “the oppressed” in general.

On the latter theme, and in words that sound like they could have been written yesterday by the suddenly penitent “woke,” Auden reflects on his generation’s adoption of radical politics in the “Red ’30s”:

Few of the artists who round about 1931 began to take up politics as an exciting new subject to write about had the faintest idea what they were letting themselves in for. They have been carried along on a wave which is travelling too fast to let them think what they are doing or where they are going. But if they are neither to ruin themselves or harm the political causes in which they believe, they must stop and consider their position again. Their follies of the last eight years will provide them with plenty of food for thought.

As Adam Kirsh informs us in his essay “To Hold Reality and Justice in a Single Thought,” Auden argued against both the totalitarian left in politics, to which he and his generation had been drawn in the ’30s, and to the fascist right in the occult poetics of the modernist generation preceding his own in figures like Yeats and Pound. Not only does “poetry make nothing happen,” to cite the famous line in his elegy for Yeats, but it should make nothing happen even on the off-chance that it could:

If the criterion of art were its power to incite to action, Goebbels would be one of the greatest artists of all time.

So much for activist or occultist poetry, each of them with a direct design on the world no less flagrant than that of the totalitarian in politics. Auden summons both the prolific and the devourer, the artist and the politician, to a necessary humility and mutual recognition, neither seeking to devour the other.3

Illustrating the problem with Auden’s sweet reasonableness, however, the more he develops his thought, the further he gets from the spirit of Blake’s myth. While Blake calls for preserving the conflict between the pair—“Opposition is true friendship,” after all—he necessarily privileges the prolific over the devourer on the proto-Nietzschean grounds that the devourer is “weak in courage” but “strong in cunning.”

By contrast, Auden, worshipping Christ, disparages the self-styled anti-Christ Nietzsche as a dimwitted Romantic throughout his version of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.4 His version reads more like their divorce than their marriage, though, a cancellation of the Romanticism that Blake incepted. Auden warns the artist against what threatens in Nietzsche and such Nietzschean disciples as Yeats to become a mere praise of strength and vitality for its own sake, whereas Blake, no less convinced than Auden that he worshiped the true Christ, lauds energy and exuberance as virtues in themselves. Kirsch explains:

Auden’s mistrust of the Big can be seen as his repudiation of the poetics of Modernism. The dictators and philosophers that Pound wrote about in The Cantos were definitely Big; so were the aristocrats and mythical Irish heroes that populate Yeats’s poetry. Modernism, one might say, was an attempt to earn Bigness, to turn reality into something grander and more perfect than it is. For poets after Modernism, starting with Auden, that kind of Bigness is automatically suspect; it has too much in common with the arrogance of totalitarianism, and not enough respect for the claims of the powerless. It is no coincidence that Auden’s understanding of history, and his conception of the poet as something like a witness, was shared by postmodernist poets such as Czeslaw Milosz, Joseph Brodsky, and Seamus Heaney, all of whom write about and against the tyranny that results when people try to impose their vision of justice on reality.

I sympathize with much of what Auden writes in The Prolific and the Devourer and recommend it to my fellows among the prolific in this period of our own retreat from maximal claims about the artist’s political efficacy.

Nevertheless, the moral hypochondria induced by the catastrophes of the midcentury, however understandable it may be, risks devouring not only the artist’s wish to “manipulate other men”—certainly a temptation we should strenuously resist—but also our freedom even to manipulate our own fantasies as we see fit.

Auden’s exemplary maturity5 is just what he said poetry should be in his essay “Writing” from The Dyer’s Hand: disenchanting and disintoxicating. But in trying to disenchant the artist with politics, Auden may also have the effect of disenchanting us with art itself, leading to the self-proclaimed hatred of art that animates (or un-animates) Beckett’s miserablist minimalism in that same brutalized generation.

The ambition to create a major work of art is not the same as the ambition to create the total state. That the activist artist of the 1930s or the 2010s maliciously or ignorantly confused these goals is no excuse for the non-activist artist to accede in the very same confusion for the apparent purpose of contesting it.

Poets should be extremists. Moderation in politics comes much more naturally to novelists, whose very form requires them to create a delicate balance of contending worldviews, as Zadie Smith and Honor Levy have demonstrated in recent weeks. But then Wystan, who knew everything, well knew this too:

The Novelist Encased in talent like a uniform, The rank of every poet is well known; They can amaze us like a thunderstorm, Or die so young, or live for years alone. They can dash forward like hussars: but he Must struggle out of his boyish gift and learn How to be plain and awkward, how to be One after whom none think it worth to turn. For, to achieve his lightest wish, he must Become the whole of boredom, subject to Vulgar complaints like love, among the Just Be just, among the Filthy filthy too, And in his own weak person, if he can, Must suffer dully all the wrongs of Man.

For those interested in Ross Barkan’s piece on men in contemporary literature and my rejoinder from last week, let me also recommend journalist James Pogue’s appearance on the New Write podcast. Pogue first brought the “New Right” itself to our attention in his controversial Vanity Fair article two years ago (and more about these reactionaries in the next two footnotes). On the pod, he makes an optimistic argument about the return of literary values now that the politicized years are in retreat—exemplified, as it happens, by the strenuous mainstreaming of Honor Levy, who’d appeared as a fringe tradcath figure in his initial New Right article. This optimism allows him to concede, despite the podcast’s overall conservative coloration, that those years also made some necessary redresses and corrections, especially with respect to the status of women in New York publishing.

Given Auden’s experience in the 1930s, it seems as if radicalism resurges in roughly 30- to 40-year cycles. We had the Civil War in the 1860s, the 1890s with their anarchists and New Women, the aforementioned Red ’30s, the militant ’60s, the politically correct ’90s, and the woke 2010s. (This can probably be traced back before the 1860s too, but, as a student of what they call the “late modern,” I leave that to historians of earlier periods.) On this theory, we can look forward to getting cancelled again, should we live so long, in about 2050.

Auden sagely explains that artists should be “apolitical,” wanting to be left alone by the state, not “anti-political,” wishing to contest state power and impose their own ideology directly. In overly political eras, he allows that artists will have to become anti-political just to preserve their basic freedoms. But once their liberties have been recovered, they should ideally lapse back into quiescence. This seems correct to me. It’s also the most illuminating way to understand the current dissensions and purity spirals now occurring on that so-called “New Right” or “dissident right” referred to in footnote #2 above.

The most notable of those associated with such dissidents, those in the orbit of the Red Scare and Perfume Nationalist podcasts, turn out, as I intimated years ago, to have been artists (or would-be artists anyway) who briefly became anti-political to get the regnant powers to leave them alone, to stop policing their speech or even (in the pandemic era) their very movement. Now that the political pressures of the last decade seem to be abating, they find themselves in conflict with the genuinely anti-political figures they’d allied themselves with. These anti-politicians wish right-wing doctrine to be enforced wherever dissidents gather.

Illustrating the sometimes psychotic horror of contamination to which political and anti-political people of all ideological stripes seem so endemically prone, and to which apolitical artists almost never are and certainly can’t afford to be, the main issue in play is the presence in these spaces of a single individual. Ironically, this individual’s transgression of what are after all only modern bourgeois gender norms, which so irritates her far-right critics, she herself defines in entirely traditionalist terms. She refers to herself as a eunuch and a castrato and has moreover never asked to be called “she” (she only is called “she,” so as far as I can tell, not because she requested to be but because she seems like a “she,” which is exactly how the gender of pronouns used to work before about 2012). (I realize this is obscure if you’re not following the drama, but usually when I allude to such things in brief someone writes a long and detailed exposé about a week later.)

Anyway, it’s past time to heed Auden’s call to separate art from politics again on both sides, any sides, every side we can find: because artists should not be dealing in “sides” at all.

The dissensions of the dissident right referred to in footnote #3 above also feature a quarrel about whether Nietzsche or Christ shall prevail among reactionaries. (The left has the same inner dialectic but tends not to express it in those terms; as Auden tells us in The Prolific and the Devourer, and very much contra Nietzsche, every true thing Marx said was said just as well by Jesus.) The Catholic Compact editor Sohrab Ahmari went so far as to declare: “There is no peace to be made between Nietzsche and Christ. It’s not possible.”

Personally, politics aside, I don’t see much of a future for Christ or Nietzsche in the oncoming Age of Aquarius unless they wed like Blake’s Heaven and Hell. We’ve been through this already at Grand Hotel Abyss, however. This marriage may be one secret meaning of my novel, Major Arcana, but it’s a not-so-secret meaning, as I told you here, of the works of Wilde and Joyce. I admit I’m shilling both my novel and my online course when I say this—petit-bourgeois to the core!—but that hardly means it’s not true.

In case you’re wondering what they’ve been up to in the world of A24 arthouse horror cinema, your intrepid film analyst went to see Jane Schoenbrun’s lugubriously stylized trans allegory I Saw the TV Glow yesterday. It’s a more literal adaptation of The Beast in the Jungle than was The Beast itself. Schoenbrun in a recent interview even refers to the way

[t]he queer philosopher Eve Sedgwick…[will] talk about, like, a Henry James novel and pick apart the queer themes that are embedded in the work, or inherent to the work, even if only in a way that feels subtle, or only hinted, or glimpsed.

Thus, this film of the unlived life concerns a man whose teenaged obsession in the 1990s with the eponymous young-adult cable-TV horror series The Pink Opaque (a mash-up of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Are You Afraid of the Dark?, as other critics have noted), and with a queer-girl classmate who shares this televisual fixation, does not alas result in his proper consummation with his interior paramour. Instead, he refuses his summons to gender heroism and lives instead into a dull and tortuously respectable cissexual middle age. That’s on the allegorical plane; on the literal plot level, the film, albeit in a derivative haze of Lynchian surrealism, dramatizes his and his lesbian classmate’s brushes with the possibility that they are living the show rather than just watching it—that, in fact, our movie’s hero is one of the TV show’s two heroines menaced by its villain, Mr. Melancholy (a Smashing Pumpkins reference to go with the title’s Cocteau Twins reference).

The trans allegory itself is so obtrusive that I wonder if the film wouldn’t have been more effective had it not simply been brought to the surface rather than left as a would-be subtext hiding in plain sight. Is the subject so unspeakable that it must be semi-entombed in ludicrously suggestive dialogue, obvious pink-and-blue color symbolism, and flagrant allusions to genre history? By the 10th or 15th time the characters uttered the cumbersome phrase “sleepaway camp,” I wanted to yell up at the screen, “I got it already!” None of this is helped by the way the lead performers were instructed, probably for some kind of Brechtian reason, to deliver their dialogue in a glacial and affectless monotone, dialogue itself more wooden than a sequoia forest.

And in fact, to excuse the way I Saw the TV Glow somewhat anachronistically presents gender nonconformity as literally unutterable, the film portrays a late-1990s public-high-school experience as if it were a period of Jamesian repression, which wasn’t my experience at all. As I once briefly documented on here, we were already toying in our art circa 1996 with ideas that wouldn’t be successfully mainstreamed until the 2010s. If the kids in the movie had just turned off Nickelodeon (the film calls it “the Young Adult channel”), which no artsy late-’90s high-school student would have been caught dead watching anyway, and picked up Vertigo Comics instead, they’d have found actual trans characters to identify with, not some strained symbolism to project onto. And then Shakespeare and James and all the rest of it—the historical avant-garde, the Beats, any queer artist or poet you want—were just an allusion away. These figures were all known in my suburban late-’90s public high school, and by a surprisingly wide range of students—pretty much anybody in the art classes I took, for example, especially since Andy Warhol was the hometown hero, buried in those very suburbs, just down the street from where I went to preschool.

This lapse in historical verisimilitude, rather than larger aesthetic flaws of the film, is finally what depressed me about I Saw the TV Glow. It almost takes for granted that the deepest layer of contemporary being, gender identity notwithstanding, is constituted by the corporate trash culture we absorbed in our youth. I’m not saying I wasn’t mesmerized by Æon Flux circa 1995, but there was so much more than that, and even that wasn’t for kids. A climactic image implies that if you cut a middle-aged Millennial open today, you’ll find an analog TV screen where our heart should be, still flickering with the children’s shows that make us the people we are (or, worse, should be) to this very day. While I appreciate the intensely media-literate Schoenbrun’s troping on the televisual invagination in Videodrome, I rebel against the idea—and against the poisonous nostalgia.

I Saw the TV Glow almost seems to look back longingly to the conservative suburban late-20th-century world it ostensibly condemns, yearning for the very closet it mourns its hero-heroine for being self-condemned to. A graffito twice-glimpsed in the mise en scène exhorts the audience that “there is still time”—time, that is, to come out of the closet, out of the tomb, to begin living rather than unliving—but the narrative’s overall effect is to lament rather the loss of childhood’s timelessness, when even bad TV felt so real you could disappear into it, and the adult shape you most wanted to take was a glittering opacity you dreamed of but couldn’t understand. I personally experienced this period of my life as a prison—all I wanted was to understand, to just become that free person already—but perhaps not everyone did, or perhaps, disappointed by adult reality, some end up nostalgic for that prison’s rules and regulations, which provided something solid to oppose and, in so doing, paradoxically set free the wandering mind.

Hence the film’s opposition of queerness to all the appurtenances of adulthood, which it relegates to the condemned category of “being a man,” as if a queer life (and/or, by the usual if often dubious metonymic extension that obtains in this area, even just an artistic life) were a matter of remaining a child forever. I wonder—actually, I don’t—what W. H. Auden would have to say about that.

I hear you about the moral hypochondria-it's the central problem I have (though he is still probably the critic/thinker who most impacted me) with Trilling. With him I think the problem is less that he was averse to major statements and more that he seemed uncomfortable with the probing, prophetic, almost gnostic half of America literature, that national voice that says (to borrow something from Bellow, who doesn't quite belong to this vein) "I want, I want!" his dismissal of Sherwood Anderson's Winesberg, Oh being exemplary. I sometimes think he'd have had us remain with the Victorians for the rest of time, and that just doesn't seem viable.

I'm curious about your negative perspective on the film, as I've been hearing mostly unqualified praise from my cinephile friends. The association of childhood with life and adulthood with stultification and regretful loss of potentiality is such a ubiquitous millennial tic that I find it almost hard to condemn any one artist for it, even as it's a pet peeve of mine as well.

"to look back longingly to the conservative suburban late-20th-century world it ostensibly condemns, yearning for the very closet it mourns its hero-heroine for being self-condemned to..." many such cases unfortunately! It's not worth reading but Halberstam's Queer Art of Failure is sort of the crystallization of the "immaturity is queer" thesis of world-refusal...

Looking forward to your Levy review, although hoping you don't join Gasda, Stivers etc in discovering supposed virtues of her prose! This shit all seems about as innovative as some 1970s post-avant-garde Philippe Sollers/Renaud Camus b-sides (guys who also went on back and forth journeys between political insanity to merely annoying literary 'experiment' and were gassed up for some years by the critics in their scenes, who ought to have known better... it's a bit like reading, today, Harold Bloom praising forgettables like Alfred Corn or Alvin Feinman as near-peers of Stevens and Crane)...