Weekly Readings #55 (02/20/23-02/26/23)

through the slow fires of consciousness into a dividual chaos

A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

In a guest essay for the

collective, I reversed the familiar trope of the technological determinism of literature—i.e., writers write the way they write because the media at their disposal made them write that way—and argued instead for the literary determination of technology. I begin with an extended reading of an Arthur C. Clarke short story in light of the Clarkesworld AI controversy, I offer examples of writers who used technology, rather than being used by it, to transform literature, including Twain, Nietzsche, and James, I provide an excursus on Joyce Carol Oates, Bob Dylan, Marshall McLuhan, and the Romantic poets, and I end with Kafka’s TikTok celebrity.This essay is an attempt to defuse AI doomerism in my corner of the discourse. While I too am intensely tempted toward AI doomerism, being not myself the world’s great admirer of ever-encroaching technology, this new panic shares for my taste too many features of climate doomerism, covid doomerism, the War-on-Terror doomerism of yesteryear, and other such “be afraid, be very afraid” warrants for state and corporate overreach. Please bear in mind that I (in my non-expert way) doubt “artificial general intelligence” is even possible. If I’m wrong, if the robots do eat us all, and they very well might, you will at least enjoy the satisfaction of saying, “I told you so.”

I am also still writing Major Arcana, my soon-to-be-serialized novel (please pledge a subscription today). I will begin serializing it before I finish writing it—serialization seems dishonest otherwise—but I at least want to have the first half not only written but also finalized, polished, shining with a high gloss, before I share anything. I destine the premiere, symbolically, for the vernal equinox.

By the time you read this, I’ll have attained 70,000 words. Major Arcana will be longer than my previous novels—you might, please, buy those while you await Major Arcana—almost certainly north of 100,000 words. As readers of Dickens know, writing serially means giving the people their money’s worth. But if Dickens is too much the sentimental populist for you, please remember also the words of no less an ironic modernist than Thomas Mann, from the preface to The Magic Mountain: “only thoroughness can be truly entertaining.”

Speaking of modernism, over on Tumblr, where readers regularly write in with questions using the “Ask” feature, an anon inquired about Finnegans Wake. In two brief pieces below, I will both reproduce my answer and enlarge upon some of its implications for creative writing. As I myself write a novel at top speed, not only unconcerned with but even slightly contemptuous of any precious verbal nicety, I want to defend such a superficially un-Joycean procedure. Finally, in a postscript also touching on Joyce, I very briefly break my political silence to revisit the post-left, specifically the quarrel between the Catholics and the Nietzscheans.

“Swishbarque”: Lots of Fun at Finnegans Wake?

On Tumblr, an anonymous reader asks:

I saw a thread floating around about Joyce’s FW. Can you share any thoughts? I somewhat recall you writing that Flaubert began the process, that culminated in Ulysses, of freezing the sentence in amber, and then FW broke it free. Perhaps the novel has been irrevocably liberated a long the

riverrun. Yes, probably the writer Aaron Gwyn, who’s done two threads now—one, two—and amusingly replied to someone who self-righteously asked how reading Finnegans Wake made one “a better human.”1

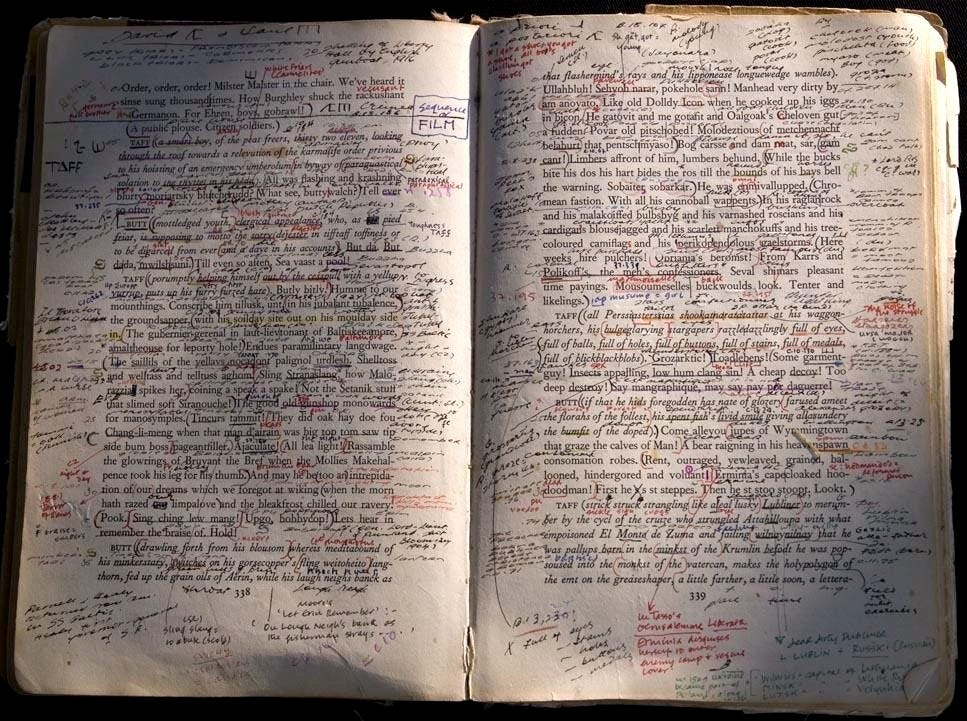

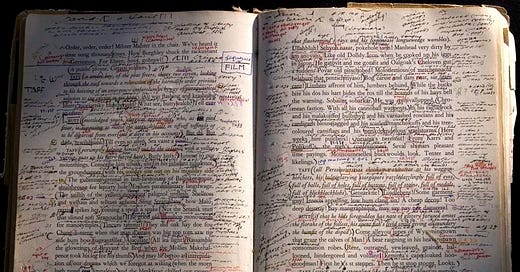

I can’t be much help, however. I’ve certainly read some of FW over the years. In Colin MacCabe’s Joyce seminar back in the year 2001 we read the Shem and Shaun part and the conclusion with Anna Livia Plurabelle; in graduate school I was in an FW reading group for a few months where we did the first 100 pages or so. But I’ve never read the whole thing, whatever “reading” here means.

I didn’t enjoy the reading group, through no fault of theirs, because they quite correctly leaned in to the aspect of the book—maybe the only real aspect the book has in the end—that calls for a cross-word puzzler’s head full of verbal trivia. This tends not to be the level on which I enjoy literature.

MacCabe, on the other hand, persuaded me of book’s weight with his psychoanalytic classroom gloss on lines like

If you spun your yarns to him on the swishbarque waves I was spelling my yearns to her over cottage cake.

A cursory Google turns up MacCabe’s interpretation here:

As Anna thinks back over her past life, she remembers how much her husband (the ubiquitous figure who is indicated by the letters HCE) wanted a daughter, hoping for a female in the family who would believe his stories, who would give to him the respect that he feels is his due. But the father is inevitably disappointed for the mother teaches her daughter that beneath the stories and the identities lies the world of letters and desire. While the father tells the son stories, the mother teaches the daughter the alphabet: “If you spun your yarns to him on the swishbarque waves I was spelling my yearns to her over cottage cake” (FW, 620). The father’s yarns (stories) are displaced by the mother’s yearns (desires); telling gives way to spelling. It is this struggle between meaning and sound, between story and language, between male and female that Finnegans Wake enacts, introducing the reader to a world in which his or her own language can suddenly reveal new desires beneath old meanings as the material of language forms and reforms.

Is this enough to make me proceed through the verbal thicket? I can’t shake the feeling that Joyce here demands too many public rights for a purely private fixation. Updike, introducing Nabokov’s Lectures on Literature:

For Nabokov, the world—art’s raw material—is itself an artistic creation, so insubstantial and illusionistic that he seems to imply a masterpiece can be spun from thin air, by pure act of the artist’s imperial will. Yet works like Madame Bovary and Ulysses glow with the heat of resistance that the will to manipulate meets in banal, heavily actual subjects. Acquaintance, abhorrence, and the helpless love we give our own bodies and fates join in these transmuted scenes of Dublin and Rouen; away from them, in works like Salammbô and Finnegans Wake, Joyce and Flaubert yield to their dreaming, dandyish selves and are swallowed by their hobbies.

This may also by true of VN’s Ada, which I never finished. We each draw the line in a different place. I’m sure I’m only denying myself an advanced form of pleasure. This is, after all, what I’d tell people who with a truculent and phony populism would spurn the incomparable joys of Ulysses.

Re: Flaubert and Joyce—I’m too lazy to hunt for it, but I think I actually said that Ulysses breaks the sentence free. Flaubert immobilized prose by turning it into blocks of precision reportage—granted, this is not quite fair to Flaubert—but Joyce loosened it up again by turning it into poetry, “poetry” implying both euphony and polysemy. Pound, quoting a German-to-Latin dictionary in ABC of Reading: “Dichten = condensare.” Finnegans Wake is, I can’t deny it, the logical-teleological next step in the Hegelian process, making every single word a whole world, Blake’s “heaven in a grain of sand.”2

Since I am not actually barred from this promised land, why do I still content myself with what Stephen Dedalus calls, with unsurprising reference not only to a book everybody knows but also to a book nobody does, “A Pisgah Sight of Palestine”? Is it time for me to give the Wake another try?

“Transaccidentated”: In Praise of Rapid Writing

Then, pious Eneas, conformant to the fulminant firman which enjoins on the tremylose terrian that, when the call comes, he shall produce nichthemerically from his unheavenly body a no uncertain quantity of obscene matter not protected by copriright in the United Stars of Ourania or bedeed and bedood and bedang and bedung to him, with this double dye, brought to blood heat, gallic acid on iron ore, through the bowels of his misery, flashly, faithly, nastily, appropriately, this Esuan Menschavik and the first till last alshemist wrote over every square inch of the only foolscap available, his own body, till by its corrosive sublimation one continuous present tense integument slowly unfolded all marryvoising moodmoulded cyclewheeling history (thereby, he said, reflecting from his own individual person life unlivable, transaccidentated through the slow fires of consciousness into a dividual chaos, perilous, potent, common to allflesh, human only, mortal) but with each word that would not pass away the squidself which he had squirtscreened from the crystalline world waned chagreenold and doriangrayer in its dudhud. This exists that isits after having been said we know.

—James Joyce, Finnegans Wake

There ends my casual commentary on Finnegans Wake in reply to my questioner—all the commentary I’m qualified to give on Finnegans Wake at this time or maybe ever—but I would like now to extrapolate from it a more general comment about the writing of fiction. Even before Finnegans Wake, Joyce, again following Flaubert, labored over every word, every sentence. Here’s the famous anecdote from Frank Budgen’s James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, too often quoted incompletely:

I enquired about Ulysses. Was it progressing?

“I have been working hard on it all day,” said Joyce.

“Does that mean that you have written a great deal?” I said.

“Two sentences,” said Joyce.

I looked sideways but Joyce was not smiling. I thought of Flaubert.

“You have been seeking the mot juste?” I said.

“No,” said Joyce. “I have the words already. What I am seeking is the perfect order of words in the sentence. There is an order in every way appropriate. I think I have it.”

“What are the words?” I asked.

“I believe I told you,” said Joyce, “that my book is a modern Odyssey. Every episode in it corresponds to an adventure of Ulysses. I am now writing the Lestrygonians episode, which corresponds to the adventure of Ulysses with the cannibals. My hero is going to lunch. But there is a seduction motive in the Odyssey, the cannibal king’s daughter. Seduction appears in my book as women’s silk petticoats hanging in a shop window. The words through which I express the effect of it on my hungry hero are: ‘Perfume of embraces all him assailed. With hungered flesh obscurely, he mutely craved to adore.’ You can see for yourself in how many different ways they might be arranged.”

You have to quote the whole thing because Budgen provides the result of Joyce’s momentous labor. So was it worth it?

At least for me, these hardly represent the best sentences in Ulysses. The grammatical reversal in the first (object before verb) is showy, gimmicky, calling attention to itself without thematic purpose or in-text motivation. In the second, the adverb “obscurely” might still, for all Joyce’s sweat, be placed anywhere—it is itself obscure—while the ly of “obscurely” and the ly of “mutely” clunk in such closeness to each other. And why “mutely” at all? Were we expecting him to bay hornily at the shop window like a cartoon dog? I concede, though, that “hungered flesh” is good.

At least here, Joyce’s fastidiousness creates more problems than it solves. He overthinks it, which makes me overthink it, and meanwhile, Leopold Bloom hungrily awaits our attention on the pavement.

Paul Valéry veritably inaugurated a certain species of modernist fiction when he told André Breton he didn’t want to write a novel because he refused to produce such “informative” sentences as, “The marquise went out at five o’clock.” One sees what he means. These words are meant to call up a chain of associations: clichéd and indifferently written realist novels about the love affairs of the upper class.

But first, as Joyce, who wrote about archetypal characters in archetypal scenarios, would be the first to point out, it’s the treatment, not the subject matter, that counts. Second, if the subject matter fascinates on its own, the language doesn’t have to call attention to itself qua language at every single point. Third, a sentence in a novel doesn’t exist by itself but as a part of a series of sentences modifying and affecting it.

As novelist and Harper’s editor Christopher Beha pointed out in an essay for The Millions over a decade ago, commenting on Valéry’s quip and criticizing its fallout in the writing workshop’s cult of the sentence,

Here is what I’m not saying: I’m not saying that writing ought to be transparent, that language that draws attention to itself is an extravagance. I’m certainly not saying that a novelist must have a “purely informative style.” Nor am I saying that style should be of only secondary concern. In fact, I still more or less think that style is everything. But style, as Proust said, is just a way of looking at the world. It emerges from the effort to express something other than itself. You don’t develop a style by writing sentences that have no purpose other than to be stylish, sentences that seek to be self-contained works of art.3

But let me inflate Beha’s modest and reasonable critique of the modernist mania for le mot juste whose logical terminus is Finnegans Wake into an untenable claim of my own: writing with an almost irresponsible rapidity is, at the very least, underrated.

Fyodor Dostoevsky wrote Crime and Punishment in less than a year, simultaneous with The Gambler, to pay off his debts. Charlotte Brontë wrote Jane Eyre in about the same time frame, after a publisher rejected her first novel but encouraged her to submit something else soon. And don’t those two long books—two of the 19th century novels still read for pure pleasure—feel, for all their length, oneiric and urgent? Isn’t a bit of smoke curling up from those pages? They don’t meet modernist standards of well-wrought prose—see how Nabokov lambastes Dostoevsky in Lectures on Russian Literature, how Woolf condescends to Brontë in A Room of One’s Own—but those books are alive. In the 20th century, Joyce’s contemporary D. H. Lawrence wrote Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, and Women in Love in the time it took Joyce to write Ulysses, and he launched a sexual revolution; Nabokov’s contemporary Philip K. Dick wrote a novel every two weeks on amphetamines and altered the very texture of the culture. In our century, both Roberto Bolaño and Karl Ove Knausgård put themselves immovably on the map of world literature by writing at top speed, Bolaño from deathly necessity, Knausgård from aesthetic desperation. From one end of the last 100 years to the other—from Franz Kafka writing “The Judgment” in one sleepless night to César Aira flying forward with each new novella, to say nothing of Jack Kerouac—some of the best and/or most influential writers wrote as fast as they possibly could. You can’t generate Finnegans Wake that way, but you can share a dream.

Even Woolf herself, despite her skepticism toward what she judged to be the emotional immoderation of Jane Eyre, disputed Flaubert’s fetish for the right word:

Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can’t use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can’t dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it.

Joyce spent “all day” on two sentences. But, when I’m working on a novel, I produce over 1000 words a day, usually in an hour or two. If I don’t write that fast, I can’t tap the unconscious. If I’m fiddling with phonemes and scrambling syntax, if I act as Stevens’s “bawds of euphony,” I will move too slow to outrun the internal censor, to find my way into the dream, to “cry out sharply.” The novel knows things I don’t, but it, whatever it is, gives intermittent access; I must, forgive the fantasy-novel metaphor, get the gold while the dragon sleeps.4

Woolf puts it with scandalous bluntness: writing a novel “has nothing apparently to do with words.” She does say, and I do agree, that you eventually have to “make words to fit” the wave of emotion, the ideas and visions, but these latter come first, and do not first come as words.

Post-Left Postscriptum: “James Overman”

So Joyce signed his letters in his early 20s. Many a truth is told in jest. Nine pregnant months ago, a right-wing anon Tweeted this ambiguous joke:

I reposted it on Tumblr with a joke of my own: I said that Wilde and Joyce had already written the gospels of this synthesis, with Wilde as Baptist to Joyce’s Messiah. To be honest, though, this is more straightforward truth than it is witty amusement. In Wilde and Joyce, we do find the mutual entanglement of Nietzschean anarcho-vitalism with Catholicism’s investment in order and beauty, compassion and charity. To elaborate on this would require a doctoral dissertation—I’m not writing another of those; one was enough—and more theological expertise than I have; but I know it by intuition to be true.

I bring it up because of the ongoing fragmentation of the dissident or countercultural right. This time they’re fighting online about whether Nietzsche or the Catholic Church should set the tone for reaction—actually, this might be all they ever fight about—with the Nietzscheans complaining that the Catholics are indistinct from Marxists in their resentful communitarianism and the Catholics complaining that the Nietzscheans are too hateful and piratical to sustain a traditionalist community.5

Both sides rightly perceive that Catholicism and Marxism—and, if I may defuse a darkly dangerous subtext by bringing it up to the light of the text, Catholicism and Judaism—have more in common with one another (all three emphasize order, tradition, theology, and community over any one person’s will) than either has with Protestant individualism, of which the anarchic vitalism of Nietzsche, the pastor’s son, is one expression.

But—if we aim at a far horizon, which all real politics and all real aesthetics should—we need both: loftily intricated cathedrals and souls vast and free enough to fill them. If you can’t see that this is what Ulysses ultimately represents, modernity’s syncretic epic and Bible in which “Jewgreek is Greekjew,” then I can’t help you.

Regular Substack readers will know I’ve been manifesting an appearance on Art of Darkness —this is a comic bit; also, I am quite serious—so it’s no wonder my Joyce inquirer begins with reference, however cryptic, to the Wake-themed Twitter threads of frequent Art of Darkness guest and Substack’s own resident Cormackian, Aaron Gwyn, who writes

on here. This is what in the manifestation community they call “birds before land.” Again, I am wholly joking (I am not even slightly joking).Much of what’s said against FW could be said against Pound’s Cantos—of which I’ve read some—and Blake’s Jerusalem—which I’ve read in its entirety, whatever (again!) “reading” here means.

Since I am currently writing a novel about an occultist comic-book writer, I observe here that I couldn’t finish either of the celebrated recent prose novels by occultist comic-book writers—Alan Moore’s Jerusalem and Grant Morrison’s Luda—because someone apparently convinced both Moore and Morrison that a novel is like a comic-book script except that every image in the image sequence has to be described not functionally but in mind-meltingly hyper-stylized language. As a result, both books collapse under the weight of their own often pointless verbiage. Moore’s novel, not coincidentally, is named for Blake’s epic and contains an extended imitation of Finnegans Wake. As far as prose fiction by comic-book writers goes: say what you will about Neil Gaiman’s American Gods—trashy, derivative, shallow, evasive, etc.—at least the thing moves.

Per the observations about literature and media in my Inner Life essay, I note that typing on a laptop makes this rapidity possible, whereas writing by hand or on a typewriter would present more physical impediments. Speech-to-text dictation could conceivably make the process even faster, but I think I’d get quickly tripped up if I tried to talk through my fantasy.

Our foul-mouthed provocatrices discuss this contretemps on the latest episode of Red Scare. As implied in a (paywalled) essay I wrote for Kat Dee’s Substack back in August, I lost interest in this scene around the time Anna and Dasha got invested in the Steve Sailer and Richard Hanania types—in what Anna herself called “racist centrism.” The moral authority of Red Scare—if one can put those words together without bursting into flame—was premised on their critique of managerial neoliberalism, whether in their 2018-2020 pro-Bernie or 2020-2022 pro-Trump phases. To evoke nostalgia for the last managerial ideology but one, however, just because it was run by men rather than women and was openly hostile (rather than quietly patronizing) toward black people, well, that’s just morally bankrupt. Still, Dasha’s Catholic Nietzcheanism may provide a few leads, and the latest episode finds her discussing a book I’ve never heard of, Maude Petrie’s Nietzsche and Christianity, a sympathetic essay on Nietzsche by a female Catholic intellectual, a nun, no less. From this, Dasha concludes that both women and Christians owe it to themselves to brave the edifying gauntlet of Nietzsche’s scorn. I added the book to my Amazon wish list—yes, you can buy books I’ve written for yourself or books others have written for me. If somebody buys it or anything else on the wish list for me, I’ll review it here (turnaround depends on book length, though: if you send me the Norton Critical Tale of Genji, you will have to wait a year).

good piece.

Add East of Eden to your list for review and I'll buy it for you.