A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week’s episode of The Invisible College , my series of literature courses for paid subscribers, is full-length and free to all: “Down the Strange Lanes of Hell,” an extravagant exploration of the controversial life and work of D. H. Lawrence. This was a fun one—I leaned in to the life here, as I don’t always do, guided by Frances Wilson’s seduced and seducing recent biography Burning Man—as we followed Lawrence from his quasi-incestuous childhood in a redbrick English mining town all the way around the world to his desert apotheosis in and around Mabel Dodge Luhan’s artist colony in Taos, New Mexico.1 If you’re curious about The Invisible College, please listen to this full episode—and then please offer a paid subscription so you can enjoy the rest. Next week: Virginia Woolf has her vision in To the Lighthouse.

My new novel Major Arcana remains available, and thanks to all of you who have purchased and are continuing to purchase it. I avoided the recent “nobody buys books” controversy, but if the average book sells only 50 copies—that was one of the shocking statistics being bandied around—I am above average. For an introduction to the novel, please see my conversation with Ross Barkan.2 You can get Major Arcana in print here, on Kindle here, or in two separate electronic formats—serial; pdf—if you are a paid subscriber to this Substack. Please contact me at johnppistelli@gmail.com or DM on here to inquire about review copies: I will give free pdfs to literally anyone who wants to write a review anywhere and will send print copies to anyone who wants to write a review in a prominent publication.

For today, I answer two reader queries: one about my favorite fascist writers (!) and one about which edition of Ulysses you should buy/read, either in general or in preparation for the the forthcoming Invisible College summer session. And don’t forget to check the footnotes for capsule film reviews, social-media controversies,3 and more. Please enjoy!

Fash Course: A Syllabus of Fascist Writers

I assume it’s because of the time spent in The Invisible College on Yeats and Lawrence, not to mention a whole ideological line of anti-moderns we’ve been tracing from Ruskin and Carlyle forward, that someone wrote in to my Tumblr and asked, “Who are your favourite fascist writers?”

Considering that “u” in “favourite,” our inquirer may want a reading list for the coming backlash against Trudeau up north. I assume it’s not because I myself seem fascistic. Someone even called me a “leftie” cultural commentator this week, after several years of people saying I was on the right. (I didn’t leave the right, the right left me!) In truth, I think the proverbial Overton Window has simply been blown to pieces in the last few months, and we’re still trying to see what ground we’re standing on beneath the shattered glass and toppled masonry.

“Fascism” is a famously hard word to define, combining incompatible elements, often little better than an epithet. As I’ve asked rhetorically before, how can Marinetti and Heidegger both be fascists, the one careering in his crashed car into the future, the other wandering the forest-paths back into the past? Umberto Eco’s “fascism is syncretic” is an inadequate explanation; all ideologies are syncretic.

Back when Joe Biden was denouncing fascism against an ironically lurid scarlet-and-black backdrop, I took the trouble to read Mussolini’s fascist manifesto. This is a curiously under-read document. Why do we spend so much time arguing about what “fascism” is when there’s a fascist manifesto to read? Then I read it and discovered why reading it is positively discouraged: if you do read this document, you will find that it is sheer folly to try to separate out fascism from modern governance tout court. Mussolini’s testament is an under-read document because anyone who reads it will either be tempted to become a fascist—or to recognize that they already are a fascist—or else to become an anarchist.4

To count as my “favorite fascist writer,” a writer has to be aware on some level, not necessarily conscious, that the fascist-anarchist spectrum cuts across the left-right spectrum, and also has to be in his or her best moments more than halfway over to anarchism.

With that disturbing preamble out of the way, my favorite fascist writers are the ones I’m focusing on in the Invisible College—Yeats, Lawrence, Pound—and for reasons that have been or will be explained in the relevant episodes.

With writers in their capacity as writers, I use “fascist” loosely and intuitively: I wouldn’t count Eliot, for example, though he probably did sympathize with some fascist ideas or parties, and the same with Chesterton. I leave it to the political scientists, but I don’t think you can be a real fascist if you’re a real Christian. A real fascist worships the old and the new gods: not the Christ of the middle millennia, but Dionysus and Wotan of the earlier ones and the radio broadcast and the image-board meme of the coming ones.

I might number Nietzsche, controversially, both among fascists and among favorites. I’d maybe also include Borges. Mussolini said, following Neetch and also (hold onto your hats, libs) his beloved Pragmatist William James, that fascism meant the imposition of will on reality: our Argentine master’s constant theme, sometimes in sorrow and sometimes in celebration. (“Whatever works,” says James. What if fascism works? James, however, was beautifully and movingly an anarchist.) For that matter, there’s our own Philip K. Dick, who quoted Mussolini’s line about the will, and who ended up wearing the label without apology in the period when he was attempting to shop Fred Jameson to the FBI.

Who else? There are good and humanly useful ideas in Heidegger about art and technology alongside the Germanic mystagogy, but as a writer he’s too abstract and philosophical for me. Marinetti’s Futurist manifestoes, his “words in freedom” are unwholesomely stimulating if you don’t take their praise of war and destruction too seriously; I’ve never read his novels, however. I also have to confess I’ve never read Céline at all, a glaring omission, considering he is always the anti-fascist writer’s favorite fascist, even the Jewish writer’s favorite anti-Semite (cf. the appreciations of Leon Trotsky and Philip Roth; the latter issued the following provocation, presumably against those who all but called him a Nazi on account of Goodbye, Columbus: “Céline was my Proust”). I’ve only read a bit of Wyndham Lewis—the big pink facsimile of the Vorticist-era BLAST they published a little while ago—and didn’t think much of it, but I’m about to read more since I’ve pledged to review a new small-press novel with an obvious Lewis influence.

Who else? Among female fascists, I have a hard time with Gertrude Stein, if she counts as a fascist, and she probably does. In the lesbian modernist quasi-fascist milieu, I much prefer Djuna Barnes’s Nightwood, as my longtime readers will already know, and if you’ve never read my nine-year-old essay on Nightwood, it might illuminate this dark question of politics and aesthetics that is the fascist-anarchist spectrum and its relation to literary modernism further.

(What about the most prominent female fascist in all the arts? Back in college, I skipped Western Civ 2 the day the professor screened Triumph of the Will. I wish I could say there was some anti-fascist principle involved, but it was just a nice early-spring afternoon and I didn’t feel like going to class. Ever since then, I’ve taken Sontag’s word for it.)5

Was Mina Loy, whose beautifully opaque Songs to Joannes provides Major Arcana with its epigraph, a fascist? Her “Feminist Manifesto” worryingly speaks of a woman’s “race-responsibility, in producing children in adequate proportion to the unfit or degenerate members of her sex.” But her “Aphorisms on Futurism” give me one of my favorite anarchist mottoes:

LOVE of others is the appreciation of oneself.

MAY your egotism be so gigantic that you comprise mankind in your self-sympathy.

I do comprise mankind in my self-sympathy, or at least I try, and for that reason I would not call for their domination or extermination, not even for the sake of the Yeatsian artifice of eternity or for the Lawrentian life-principle to which I am otherwise, in my ambitions for myself and for mankind, undeniably drawn.

Heterotextuality: Which Edition of Ulysses Should You Read?

With the Invisible College’s summer reading of Ulysses in view, another anonymous inquirer wrote in to ask:

Does it matter which version of Ulysses I read for the course? Could you briefly summarise the differences? (I am tempted to add, like Conrad, “spare me the details”—except I expect them of revealing)

The entire enervating controversy (yes, there’s a controversy!) is summarized in this New York Review of Books article from 1988. Editor Hans Walter Gabler, whose controversial edition I will be rereading this summer, deployed exceptional editorial methods—including an early practice of what we might in retrospect call digital humanities—to amend or restore (or recreate) an exceptional text:

An editor of Ulysses might take, for example, either the 1922 first edition or the 1961 Random House edition as the copytext and compare it with all available manuscript sources and any subsequent editions that Joyce reviewed or corrected. Theoretically, at least, the result would be a version that was closer to Ulysses as Joyce intended it for print. Gabler, however, decided that all previous editions of Ulysses were too corrupt to serve as copytext. He therefore chose not to correct any single version, but to reconstruct Ulysses by tracing and collating the various stages of Joyce’s actual composition.

Despite the controversy, the Gabler edition remains favored by academics; it’s the one I was assigned in graduate school, and it has all my notes in its margin. My first reading, however, was of the Vintage paperback based on the 1961 Random House text that incorporated Joyce’s corrections made in the ’20s and ’30s to the error-ridden 1922 edition. (The Modern Library hardcover, still widely available, also uses the 1961 Random House text.) This edition charmingly reprints as preface Judge Woolsey’s ruling that lifted the ban on the novel in 1934, on the grounds that its effect on the reader is “emetic” rather than “aphrodisiac,” and that, in any case,

In respect of the recurrent emergence of the theme of sex in the minds of his characters, it must always be remembered that his locale was Celtic and his season spring.

For my money, the most thematically consequential variant between the two editions is in the wording of the telegram Stephen receives in Paris informing him of his mother’s terminal illness. Joyce meant the telegram to contain a meaningful error, which printers or editors “corrected,” a faux-correction that made its way all the way into the 1961 edition, until Gabler restored the significant mistake, a poignant pun encapsulating the moral state of Dublin in 1904: “Nother dying come home father.” That and, with equal oedipal force, the more famous passage of the Gabler where, in the “Scylla and Charybdis” episode, “love” is revealed to be “the word known to all men” to foreshadow Stephen’s later and otherwise mysterious plea to his mother’s shade, “Tell me the word, mother, if you know now. The word known to all men.”

But I don’t really think it matters if you read the 1961 text or the Gabler. Endemic errancy of language is one theme of the novel and of Joyce’s errant corpus at large—a theme with ethical weight, even (Stephen’s scholastic fixations being symptomatic in the novel of his “general paralysis of the insane,” for example). Despite his protestations, the instability of the text seems to me to be one of Joyce’s hoaxes on his future academic readers. Try to imagine Joyce not satirizing the quarrelsome, quibble-ridden scholars portrayed in the NYRB article!

That said, I’d probably stay away from facsimiles of the 1922 edition, even though everybody’s publishing them now that this particular version is out of copyright. This rule has an exception, however: the Oxford World Classics edition does use the 1922 text but has an impressive scholarly apparatus explaining errors and variants.

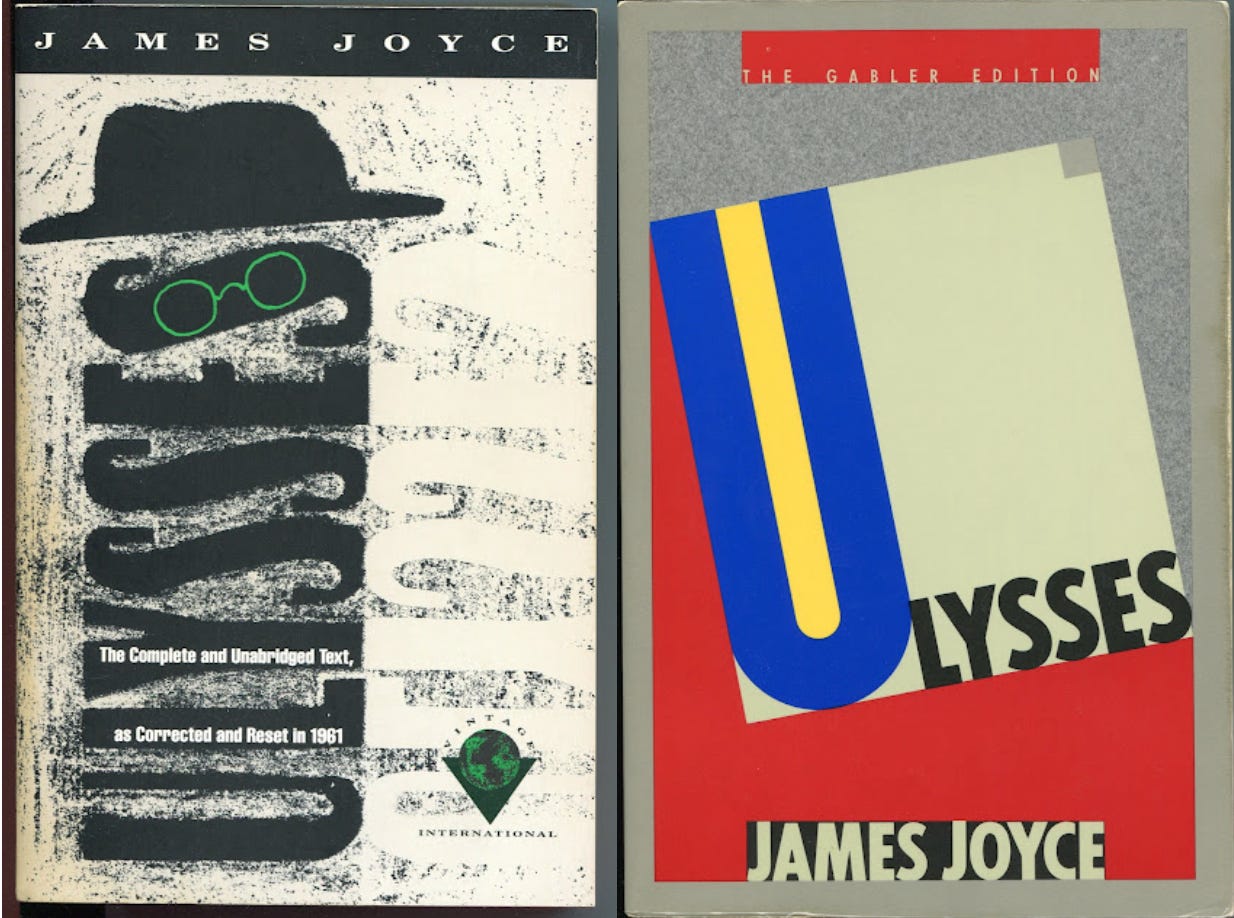

Aesthetically I prefer the ’90s-era Vintage paperback where the title, running vertically in a stencil design down the left side of the front cover, is supposed to signify Bloom’s figure, topped by his hat and Irish-green glasses. This, coupled with an ink-spattered grayish background, to my mind captures in a brilliant visual abstraction the “feel” of “dear dirty Dublin,” especially from the point of view of the book’s many scribblers, printers, admen, and chatterers: men made of words wandering a city made of words. The Gabler edition by contrast sports a vaguely Constructivist cover; as Brian A. Oard once quipped in a post containing both visuals, as pictured above, it “makes me want to build a dam for Lenin.”

With Lawrence as with Yeats, however, friend-of-the-pod Paul Franz is the resident expert and miglior fabbro. See his recent essay, peer-reviewed even, on Rachel Cusk’s engagement with (not to) Lawrence. Now that I have taken the Mabel Dodge Luhan pill, maybe I will read Cusk’s Second Place, after having left Outline unfinished as another wearisome Sebald pastiche, and with an off-putting font to boot, like an instruction manual.

And congratulations to Ross: he called Major Arcana the “elusive great American novel for the 21st century” and now has a great American novel of his own coming out next year.

This footnote is a case in point. In these posts, I often comment on the week’s literary-world social-media controversy. I must abstain this week, however. Just before the controversy kicked off—you can read the irritant here—I successfully manifested for myself a review copy of the book in question and a prominent venue to review it in, so please stay tuned. By “manifested for myself,” I mean I wrote on Substack Notes that somebody should have me review the book in question since I’ve been casually commenting on the author’s work for years now, and an editor read my Note and did just that. As Ray Bradbury teaches, much of what might be called “manifestation” is just asking clearly for what you want. I’m not going to pull the “you’re just, like, jealous” card, but some of the excess affect involved in this week’s lit-world online contretemps undoubtedly involves a bit of envy on this point. The offending author is, as Invisible Collegians will learn this week, no less parentally privileged or cool-kid-connected than was Virginia Woolf. Which by itself doesn’t mean her book is as good as To the Lighthouse—or that it’s not. I’ll let you know.

Along these lines, I suggested in the Invisible College’s Dickens episode that the word “fascism” often functions as the scapegoat for the unsavory aspects of the three other modern ideologies, which are considered legitimate, as fascism is not: fascism takes the blame for the conservatives’ traditionalism and communitarianism, for the liberals’ inherently biological (because wholly secular) conception of human life, and for the socialists’ totalizing cult of the state, each of which in its way justifies the disposability of whole populations that supposedly renders fascism alone illegitimate. Mussolini, a Hegelian and ex-Marxist, emphasizes the latter, the cult of the state, so much so that his version of fascism dismisses nationalism, since it is in his view the prerogative of the state to define the contours of the nation. This is no surprise since the politically procedural corollary of nationalism is in fact democracy—the self-governance of the national demos. But this is (to borrow a phrase) an inconvenient truth for all parties.

Speaking of cinema and modernism—this is a bad transition, but please let me have it—now is as good a time as any to say that, after viewing it yesterday, I remain curiously haunted by The Beast, my first Bertrand Bonello film, an adaptation of Henry James’s The Beast in the Jungle by way of Cloud Atlas’s kaleidoscope of past, present, and future lives seeking their fulfillment through time. (For my excessively provocative reading of James’s great novella of the unlived life, see here; for my explanation of why Cloud Atlas has become a veritable genre unto itself in our narrative century, see here.)

The film’s science-fictional conceit is that in the near future, A.I. will, if we humans want to work in the decimated economy, force us to relive our past lives to eliminate the negative affects caused by our accumulated traumas. Consequently, our heroine, played by Léa Seydoux, must re-experience her past encounters with a man who first appears to her as a would-be lover in 1910 Paris and then as a misogynist murderer in 2014 L.A.—a man she meets again in the very 2044 Paris where she is attempting to cleanse herself of his lingering effect on her metempsychotic soul.

Bonello’s human-resources dystopia takes aim both at A.I. itself and at the therapeutic state, effectively identifying both as enemies of the constitutively human, which includes, whether we like it or not, all the affects, positive and negative. (I wrote here about why writers and artists are often—and are often right to be—hostile to psychology and psychotherapy.)

As in Cloud Atlas itself—novel, not movie—the past was much better realized than the future, though Bonello’s Lynchian near-present L.A. is undeniably unsettling, perhaps the most lively of all the film’s temporal settings. Léa Seydoux’s anguished and disoriented triple-timeline performance, half-drama, half-horror, is an undeniable feat, seamlessly combining “scream queen” with “Merchant/Ivory,” while George MacKay acquits himself elegantly as an English gentleman in Belle Époque Paris, creepily as a homicidal incel in 2010s America, and colorlessly as a drone in A.I.-dominated future Paris. If this film has been advertised to you as “co-starring Dasha,” however, please be aware that everyone’s favorite Byelorussian provocatrice is only onscreen for about three minutes.

All in all, I understand Bonello’s glitching, dreaming, gorgeous, anxious meta-cinema, this neo-tragic neo-romance, to warn us against letting anyone else live for us or convince us not to love, whether “anyone else” is a machine or another person or (vide Henry James’s Beast) ourselves. As James wrote elsewhere, “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to.”

Partly (who am I kidding, mostly) in response to the veiled resentment I read online this week—so thin and venomously precious it spun from gossamer—I pre-ordered her book. How dare she have the wily temerity to proudly unleash what is possibly a clumsy but ambitious first collection into the world! (But I must say, the self-flagellating hedge of that all-too-clever title doesn't inspire confidence. I thought she was a blackpilled zoomer, not a "so... I did a thing" smol bean millennial?) From what little I've read, a Woolf she ain't, but Godspeed to any cocksure debut author who ardently lets loose a Ginsbergian howl. Greatly looking forward to your review!

For whatever reason the Ulysses that’s found its way into my hands is primarily the 1961 edition, although I have an earlier, late forties hardcover lying around somewhere. I respect the book but I can’t imagine ever being the sort of person who reads it closely enough to put much thought into the variations-my experience with it is a bit like Borges! The thing about “fascist” literary figures is that seemingly anybody in the early 20th century who wasn’t a Dos Passos style Marxist could be described as such. I’d probably go with Lawrence for the anglosphere and Hamsun (who was I believe an actual hitlerist) for the European world. In the postwar period it’s probably Mishima.