Weekly Readings #101 (01/08/24-01/14/24)

in a Starbucks in Atlantis

A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I published “The Interrogation,” the final chapter of Part Three of Major Arcana, my serialized novel for paid subscribers. For the reverberations of its climactic revelation, and even the reverberations of Part Two’s climactic revelation, you will want to read Part Four, which begins on Wednesday. There we rejoin the story of Ellen Chandler more than two decades after we left it. Please subscribe today!

I also reposted my 2015 essay on Northrop Frye’s epochal Anatomy of Criticism, which I surrounded in the form of a generous preface and copious footnotes, with my thoughts on Frye and his work from the vantage of 2024. This is all in preface to the first meeting-episode of The Invisible College, my year-long casual course on modern British and American literature for paid subscribers. School is in session on Friday with a discussion of William Blake.

For this week, I reply to my critics, continue thinking about Blake and his critics (Frye again but also Paglia), and finally string together some loose thoughts posted over the last several years on my Tumblr about why I’m not a materialist, why I believe in strange archaeology, and what it all means for nature, humanity, and even Major Arcana. Please enjoy!

Theories of Everything: Poetry and Criticism in Deep Time

People ask me things. Then other people get mad when I answer. Someone wrote in wanting to know what I have against anime. I wasn’t even aware I had anything against anime, but the audience, like the psychoanalyst, hears the story you don’t even know you’re telling. So I answered, diplomatically and even humbly—though I am as a rule so sickened by humility—and for my pains I received this rebuke from some anon:

Your inability to engage with art on its own terms and then form aesthetic judgments on it anyway continues to baffle and mystify me.

I never like to get drawn into the online morass of fighting with actual persons, of returning insult for insult, of responding to this in the way one, in one’s heart of hearts, would like to respond to this, with something on the order of, “Kiss my ass, suck my dick, and go fuck yourself!” Instead I will rest my case on Wilde’s rejoinder to Arnold. Arnold said the critic’s goal was “to see the object as in itself it really is.” Wilde replied that “the primary aim of the critic is to see the object as in itself it really is not.”

That’s a provocation, but I would more seriously argue that we don’t want individuals—not critics, not artists, not even the people we know in our lives—not to have boundaries, to be indiscriminately and amorphously open to every kind of experience. They would not be individuals. How then would we love them? We have learned too well the lesson of prejudice taken too far and have forgotten the problem of prejudice not taken at all. I’ve already quoted in these electronic pages a passage from an old professor of mine who must here remain nameless:

Identification as readerly strategy belongs to the New Old Right,1 which is why we don't have to throw out Adorno because he rejects, for example, Jazz: it is only the uncritical desire to seek a Master, thus to be a Slave, that would demand of a great thinker that his taste always be correct.

We wouldn’t want Adorno to have liked jazz, and we wouldn’t want me to like anime. We wouldn’t want a William Blake who did not see fit to pronounce illegibly on the whole of human and universal destiny, and we wouldn’t want a Northrop Frye who did not explicate Blake in the full faith that the poet’s pronouncements were sound. If any author was totally right, we would need only to read that author. We would be deprived of the whole discordant concert of wrongness, which in its strange emergent harmonious totality is the only rightness available to us. “Opposition is true friendship”—remember?

I segue into Blake because I wonder if recent discoveries in archeology haven’t proved some of his more dubious-sounding pronouncements more correct than we thought. I know much less about archeology than I know about anime, but I essay the topic anyway. Trying rather desperately, out of scholarly decorum, to insist that Blake might have been familiar with some dry, forgotten theological text he would like the poet to have been responding to, Frye amusingly describes Blake’s research methods, which are my own:2

Blake, though he was not likely to have read such a book through without some powerful stimulus, may have read the first twenty pages of practically anything, and there is no reason why Butler’s book should be an exception either way to that important principle.3

I was rereading Camille Paglia’s chapter on Blake in Sexual Personae, by the way. It begins with an unfair dismissal of Frye, asserts en passant that no critic has connected Blake to the contemporaneous Gothic movement (Frye makes just this connection), and is in general a refreshingly pugnacious, personal, and Wildean declaration that Blake’s poetry both makes no intellectual sense and that the emotional sense it does make diverges radically from what apologists like Frye and Harold Bloom claim on the poet’s behalf. She essentially charges Frye and Bloom with a straight-male-brained Protestant-Jewish autistic fixation on textual meaning, whereas the point of poetry is what it feels like to read it, and this only the Catholic lesbian-but-male-homosexual-identified critic-who-has-read-Freud-properly understands:

I reject criticism’s tidy assessment of Blake’s sex theory, where redeemed imagination opposes and reconciles civilization and nature. Poetry is written and read with emotion, not mind. Emotionally, Blake’s world is out of control. […] Translating him into moral terms, criticism is at odds with how Blake’s poetry feels. Bloom presents Blake as a man of peace who hates war. But Blake’s prophetic poetry is war, violent, terrible. His long poems seethe with hostility, of which his obsession with mother nature is but one example. As I read the accumulated criticism, I keep asking, why is Blake a poet rather than a philosopher, if everything he wrote reduces so neatly to these manifest ideas? Blake scholarship denies there is a latent content. In life as in art, moral flag-waving may conceal a repressed attraction to what is being denounced.

Paglia seems to dislike Blake for his own monstrously evasive dislike of women, gays, and androgynes, more of which below, though she tempers the possible “political correctness” of the accusation (I suspect she agrees with him—I certainly agree with him—that “accusation of sin” is the most Satanic thing there is) with her customary almost novelistic sympathy for what drives men in these matters:

Remarkably, Blake’s crystal cabinet imagines female genitals at a high degree of artifice. There are few parallels. Female genitalia are not beautiful by any aesthetic standard. In fact, as I argued earlier, the idea of beauty is a defensive swerve from the ugliness of sex and nature. Female genitals are literally grotesque. That is, they are of the grotto, earth fissures leading to the chthonian cavern of the womb. Italians have a special feeling for grottos and are constantly building them behind homes or churches.4 It is part of our pagan heritage, our ancestral memory of earth-cult. Female genitals inspire in the observer, depending upon sexual orientation, that stirring in the bowels which is either disgust or lust.

We wouldn’t want an Adorno who liked jazz, and we wouldn’t want a Paglia who didn’t identify with a certain primal male horror of the vulva.

And yet, there may be something to Blake’s archeological and anthropological speculations. Paglia famously accepts the feminist theory—now repopularized among the literati by Tao Lin’s Trip and Leave Society—that humanity at large began in what today’s right-wingers now call the matriarchal “longhouse” and then evolved into organized civilization and glorious artistry through men’s ambitious, projective attempts to escape this crushingly maternalistic constraint. She differs from the feminists only because she thinks this skyward phallic thrust out of the matriarchy was a good thing.

For Blake, however, and I here rely on Frye’s explication, the matriarchy didn’t occur within history but is the frame of history itself. Femininity is nothing less than the external nature in which the world-soul has been imprisoned since the self-division of God, the gnostic Creation-Fall.

For Blake, in theory, masculinity and femininity are equally bad because equally symptoms of the Fall, of the brokenness of the totality that was God. Both masculinity and femininity have to be redeemed in the sacred union of marriage before the soul can progress to its reawakening as the God-self—progress from Beulah to Eden, to put it in Blake’s quasi-private idiom. Blake therefore condemned the phenomenon of androgyny for perpetuating the same fallen blurriness as does chiaroscuro in painting, which he likewise despised.

Paglia points out that Blake couldn’t here be any further from the attitude adopted by later Romantics. For them, though they were in effect no less gnostic than Blake, the androgyne was the most utopian sexual persona of all, standing for the self-sufficiency of art contra naturam. (Art is “self-sufficient” because, through what we would now call both its mimetic and its memetic reproduction processes, it generates life out of life without having to pass through the natural media of sex and the sexes.) The androgyne is accordingly the very paradigm of the artist in Coleridge and Wilde, in Woolf and Joyce, even in conservative Eliot with his visionary Tiresias.5

Within the matriarchal frame of mother nature, however, history has been the nightmare of a sacrificial patriarchy, the Druidic male order of priests slaying victims to propitiate mother nature in the earth on behalf of father god in the sky, though neither this mother nor this father really exist except as fragments of the former wholeness that we reify because we don’t understand them as such. Frye explains:

The victory of the sky-god over the Titans means that this universe slowly became more orderly and predictable, and that men, weaker than the Titans but still gigantic, turned to internecine war as history enters the “Moloch” brazen period. The new thundergod of moral law and tyrannical power, whom Blake calls Urizen, was a projection of the death-impulse, and these giants, at the nadir of the Fall, worshiped him in a cult of death consisting largely of human sacrifices. Since then, the belief that somehow it is right to kill men has been the underlying cause of all wars.

This is the period of Druidism, when giants erected huge sacrificial temples like Stonehenge and indulged in hideously murderous orgies. The burning of great numbers of victims in wicker cages went on for centuries and is referred to by Caesar and other Classical writers: Blake, for some reason, speaks of the “Wicker Man of Scandinavia,” where such practices, according to his authority, were unknown. Early explorers found the same custom in Mexico, indicating the world-wide spread of the Druid culture. The main characteristics of Druidism, to be treated in more detail later, were megaliths or temples for human sacrifice, sun worship, serpent worship and tree worship—in Britain, of the oak.

And here we arrive at today’s archeology. Just this week, they found a metropolis in the Amazon. Increasingly, it appears that civilization has been at once universal and global, the typical or at least the aspirational state of humankind as such. There are no savages. Everyone is pretty much like us, every time pretty much like now. Sometimes they failed, and the jungle overgrew their ruins, and they ended up foraging in the forests to be mistaken by explorers as the type and form of “primordial man” when they were actually the type and form of “belated man.” But this could just as easily happen to us, too, and sooner than we think. Grant Morrison somewhere recalls speaking to an Aboriginal Australian, and this Aboriginal said to Morrison of the moon, “Oh, we’ve been up there—plenty of times!” I suspect he was right. How many times have we been to the moon? What counterpart of mine typed his weekly newsletter in a Starbucks in Atlantis 10,000 years ago?

This idea is a welcome disaster for our politics, by the way, since, as Paglia herself explains, the right is based on Hobbes’s state of nature, the left on Rousseau’s, and without either Hobbes’s ignoble savage or Rousseau’s noble savage as the antitype of “civilized man,” neither right nor left make much sense. What if we took the artistic imagination as the primary and central fact of humanity?

With that question, I repost here a trilogy of old Tumblr posts spanning the last two years or so. They chart my own increasing attention to this subject of our ancient lineage. I have characteristically added footnotes.

For and Against Iconoclasm

First is my commentary on an article in Palladium6 titled “Why Civilization Is Older Than We Thought.” I wrote:

This an intriguingly speculative, wide-ranging article, and the accompanying podcast might even be better. In the latter, Samo Burja posits two models of civilization, Steven Pinker vs. Robert E. Howard. For the Pinker model, civilization is an inherently teleological logic and automatic process, getting better all the time from a few basic premises as we hop, skip, and jump our way from Athens to Rome to Florence to London to New York; the Howard model, which is supported by the discovery of scattered, lost civilizations more ancient than the consensus date for the arrival of agriculture 10000 years ago, some buried in the sea, suggests by contrast that civilizations rise and fall all the time because their material and cultural infrastructure and the knowledge to sustain them are extremely fragile. Some are forgotten; what survives of others is arbitrary; Plato, Burja suggests, may have been the equivalent of a blogger (a thought I find comforting rather than disturbing).

Burja emphasizes that we find only what we’re looking for in the past. Ideological frames necessarily distort even empirical findings in archeology, which, given that it’s an expensive science, they also physically control and constrain. Totalizing worldviews from Marxism to Islam seek to suppress inconvenient facts, for example, while modern nations from England to China wish to establish sometimes spurious ancient lineages.

He also ruminates on the role of iconoclasm in destroying evidence—and of destroying civilization in the first place. Ironically, pervasive iconoclasm stemming both from Athens (the aforementioned Plato) and Jerusalem (the First Commandment) might account for western dynamism, even as iconoclasm declares war on civilization at large, as all the book-burning, church-bulldozing, and statue-toppling from the Library of Alexandria forward would suggest. Having been reared just before this century that symbolically began with the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, I fear the iconoclastic impulse, as I’ve said here before; I like libraries and museums; I want to preserve the works of humanity, not destroy them in the name of a bodiless ideal, be it reason, God, or justice. But I admit in theory that the dross has to be burned off from time to time—that the prohibition on idolatry encodes a real insight—no matter how much I want to keep myself and my works from the flames. (See my prose poem or flash fiction from 2015 appropriately titled “Iconoclasm.”)

While this whole topic of ancient civilization is beyond my expertise, I did touch on it in my recent piece on the Iliad, for which I also read Adam Nicolson’s Why Homer Matters. (Fun fact for the Woolf-pilled: Nicolson is the grandson of Vita Sackville-West.) Despite the title, which suggests some Western-Canon-style argument for the value of the classics, Why Homer Matters is more an investigation into the civilizational origins of the Homeric epics than anything else; Nicholson hypothesizes that the epics embody and preserve the divided consciousness of an originally nomadic people—the Greeks in his view went south to the Mediterranean from the Eurasian steppe—who became a settled agricultural and urban order, hence the Iliad’s central conflict between the warrior band and the city.

Against Cultural Materialism

Second, and in sequel to the first, is my commentary on a Spectator article titled “Is an Unknown, Extraordinarily Ancient Civilisation Buried Under Eastern Turkey?” I wrote:

The answer appears to be yes. As we saw last year, with the discovery of these sites over the last few decades, it appears the experts’ picture of human history has changed in ways that haven’t yet filtered out into pop culture.

First, civilization is much older than we thought and may pre-date the rise of organized agriculture—may in fact be religiously inspired rather than religion’s having been the ideological excrescence of human settlement. Cult, cultus, culture: this is where we start; this is who we are. And this, to my mind, deals a welcome blow to the dull and depressing fetish of cultural materialism, i.e., explaining our ideas by our circumstances, as if we were just the playthings of the environment and our hapless attempts to accommodate ourselves to it, rather than imaginative agents renovating the world in the name of metaphysics and aesthetics.

If the religious origin of civilization is cheering, however, this new deep history is also brutal and unsentimental: we can’t blame agriculture for hierarchy and patriarchy anymore, since it appears there was no peace-loving egalitarian goddess cult in the womb of time, but only sacrifice on the altar of the phallus all the way down. I wonder: might agriculture itself have been the matriarchal innovation? “Come away from the great stone chambers of your penile death cult and settle down on the farm, man—pray on the hearth to mother earth for the harvest.” An unwarranted speculation, I’m sure.

I don’t mean to disparage the expertise of archeologists and related investigators; it’s just that my own life in academe as a student of modern literature was spent observing fierce feuds over the meaning of texts written within the last 100 years in our own language by people who were the contemporaries of our parents and grandparents. So the significance of objects 13000 years old from a barely-understood alien civilization is probably a permanent mystery, especially when you consider the wit and irony, as well as sincerity and solemnity, with which we as a species like to deck our imaginative productions, even in worship.

I re-watched the great film Altered States (1980) last night, that doomed confrontation between director Ken Russell and writer Paddy Chayefsky over a hallucinatory parable about a scientist dangerously seeking human origins. Pauline Kael, insulting the film, actually described what’s pleasurable about it: “Russell, with his show-biz-Catholic glitz mysticism, and Chayefsky, with his show-biz-Jewish ponderousness.” The movie’s moral—one thing, I think, Catholics and Jews can agree on, in defiance of our modern gnostics—is that there’s no great truth to be found in the primordial, but merely the baleful chaos out of which we were lucky enough to climb to build the works of intelligence and love.

The skull-piled phallic death chamber—if that’s what it is—is an imperfect example, we might say, still more than half chaos, not yet illuminated by the insight of proper religion and art, which is that you don’t actually have to kill anything for the chaos-calming ritual to work, but a wrong step in the right direction nevertheless. If it started earlier than we thought, and possibly from imaginative promptings alone, so much the better.

Why I Am Not a Materialist

Third and most recent is my answer to a reader’s question about why I am not a materialist. I wrote:

We live inside of ideas concretized as sculpted landscapes, physical structures, technologies and tools, and language itself. In spite of Marx, the working class keeps voting on the basis of culture; in spite of Darwin, we still choose strange-looking lovers.7 Even Marx allowed that human beings, unlike bees and beavers, build freely and in accordance with beauty rather than necessity. Even Freud granted that most of human sexuality is, strictly speaking, perverse, not focused on the reproductive organs and their function but on all manner of fetishes, literally from head to toe. Scientists can’t seem to prove that the brain is the locus of consciousness, nor do they seem to know what consciousness even is. The quantum physicists, if I understand them, posit a reality defined at the subatomic level by the observer. The archaeologists keep pushing the advent of civilization further and further back into the past, with deterministic models (e.g., civilization requires agricultural settlement) increasingly challenged and cult and cultus appearing to be the driver. Every third or fourth person has seen a ghost. What material interest of yours is served by your desire to know why I’m not a materialist? Almost everything in human life is beautifully gratuitous, irreducible to need and program. That there is something rather than nothing remains both a miracle and a mystery.

Don’t get hung up on the political imprecation, as he was writing in the thick of neoconservatism, back in the mid-1990s. Almost a generation later, the scene has changed. The New New Left is the Old New Right, in the sense that the Trump-era #resistance has been more or less neoconservative in outlook and even in personnel, while the New New Right is the Old New Left, irrationalist and Nietzschean. They call it “the mystic Right”:

As a footnote to this footnote: this will take a generation to work itself out, but what an anti-climax for the New Right or “mystic Right,” to end that list with any version of “Auto-Lit.” In retrospect, the literary monuments of the New Left, a “mystic Left” that also reposed its faith in the Age of Aquarius, turned out to be the mature novels of Pynchon and Morrison. These grand fantasies are as far from auto-anything as you can get, with Pynchon totally withholding his life from the public and with Morrison sometimes expressing a mild contempt for the autobiographical impulse in fiction. She refused to write a memoir because, she said, her life was boring; I suspect she was being diplomatic—her life was pretty interesting—and really meant the form was boring. Joyce, a mystic leftist in his own time, to counter-balance the mystic-rightism of Yeats, is a grand exception here, but he so totally transfigured his own life in its recreation into art that he manages to evade the distinction. He wrote supreme fiction, much as any fantasist, not just his Casanova diaries. Joyce aside, though, and ignoring the porous left-right distinction as well, I really think writers should try to make up crazy stories. You wouldn’t have your “Dune Armor” if Pynchon and Morrison’s politically ambiguous contemporary Frank Herbert, a visionary inspiration to New Left and New Right alike, hadn’t made up a crazy story. Hence, in response to this viral Xost—

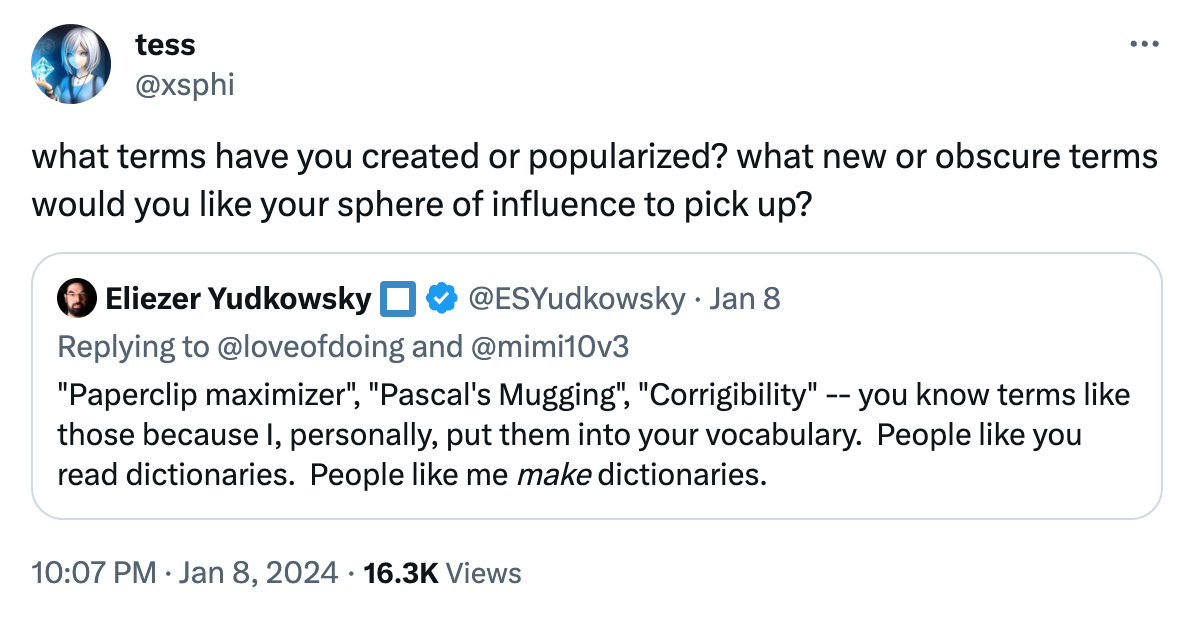

—I would most like to meme “romantic realism” into the discourse as an important counter to “auto-lit,” whether of leftist, rightist, or centrist varieties.

As they are Ash del Greco’s. You can take this whole post, by the way, as an explanatory footnote to Ash del Greco’s perhaps mysterious speech to Jacob Morrow in Major Arcana, Part Three, Chapter 13, “Hollow Lake”:

“We live only for the sake of the imagination. I saw somewhere online, I don’t know where, that they keep digging up cities thousands of years older than their previous earliest estimated dates for the development of civilization. Cities from before agriculture, cities built by nomadic rather than settled peoples. If they had no grain to store, no permanent settlement to stabilize, why did they send towers and temples into the air? Apparently, they built those structures for the purpose of human sacrifice. Those earliest stone towers housed stone gods who held their stone penises in their stone hands to watch as the first builders of cities sent heads rolling in spurts of blood across their stone altars, as mounds of skulls massed against the stone walls.”

When I wrote this, I didn’t know (consciously) of the role stone played—as the solid dead bottom of the Creation-Fall temporarily blocking the resurrection, like the stone before Christ’s tomb—in Blake’s gnostic cosmological symbolism. The entire portrait of Marco Cohen also seems unconsciously borrowed from Paglia’s chapter on Blake.

Blake couldn’t be more distant in attitude from the Enlightenment’s (and perhaps the English language’s) greatest literary critic, Samuel Johnson. Yet there is that famous anecdote about Dr. Johnson, responding to an interlocutor who was shocked the critic had not finished reading some then-fashionable book but had only “looked into it.” “What, have you not read it through?” the man asked, to which the Great Cham replied, “No, Sir; do you read books through?”

Her deliberate overstatements are so funny, and her moralistic critics take them with such stupid literalness. The only time I am ever tempted to claim anti-Italian-American discrimination is when critics don’t even seem to notice that DeLillo and Paglia are hilarious in the two characteristic modes of Italian-American humor: the deadpan parody of received wisdom and the camp-operatic exaggeration of the same, respectively.

All of the concessions made in Major Arcana to the sensitivity reader in my head take the form of little scenes meant to clarify that this ontological androgyny of the artist is the novel’s theme, not transgender identity. The confusion of these two subjects is one of the social, political, and even medical defects of our era, and on “both sides.” It’s why, for example, as a number of bemused centrist commentators have pointed out, there are plenty of high-profile transgender conservatives but no nonbinary conservatives, since “nonbinary” signals a political commitment facilely equated with metropolitan artistic identity as much as it does anything else—though I would argue that the political and the aesthetical-metaphysical are being fatally conflated in this case, too, and that everybody would be better off if they paid almost no attention to politics, democracy being, for all practical purposes, presently inexistent anyway. Hence I occasionally bring normie transgender characters onstage to say to Simon Magnus and Ash del Greco, in effect, “You’re not trans—you’re crazy,” “crazy” here meaning, in normie terms, an artist. One may of course be trans and an artist, i.e., crazy, just as one may be cis and be an artist, but the problem of the artist aspect of the soul’s essential androgyny remains and cannot be dispelled simply by adherence in every other area of life besides art to masculine or feminine, whether cis or trans. My sole concession to the otherwise fascistic #ownvoices mentality is that the trans artist’s specific negotiation of this complex subject is almost certainly best left to trans artists themselves to explore. As far as Simon Magnus and especially Ash del Greco go, however, they in their particular craziness essentially are #ownvoices characters. As Jack Kirby strangely and wonderfully once said of Galactus, I’ve known them for a long time.

Insert here more commentary than I can provide on the increasing role of Palladium in our politics. This organ, which has been called “neoreactionary,” also collaborates with the proverbially “globalist” World Economic Forum, even as its plausibly racist warning of a coming DEI-enabled catastrophic “competence crisis” has been cited by Elon Musk himself.

Frye implies that Blake would have rejected the theory of evolution, and even that his poetic argument would be clearer to us if he’d had Darwin to wage it against. Blake was crazy, after all. But why don’t you take it from Guy Davenport instead? He’s having a richly deserved revival, because his great essay collection, The Geography of the Imagination, is being reissued this month, with Becca Rothfeld rightly saluting the modernist-generalist in the Washington Post. In that book’s magisterial essay on the 19th-century American biologist Louis Agassiz, who also rejected evolution, Davenport likewise reproves Darwin and stands up instead for the more poetic or Blakean consciousness of nature he finds in Agassiz:

For Agassiz, who discovered the Ice Age, time was no strange subject. But in the puzzle of seeming Ur-parents and infinitely varied descendants he was more modern. He belongs to the spirit of Picasso and Tchelitchew, who have meditated on change as infinite variety within a form, theme variations made at the very beginning of creation, simultaneous. The ideas of nature were for Agassiz what an image is for Picasso. Genus and species are perhaps ideal forms from which nature matures all the possibilities. Time need not enter into the discussion. Snake and bird and pteridactyl all came from the same workshop, from the same materia available to the craftsman; they do not need to be seen as made out of each other. An artist fascinated by a structural theme made them all. Darwin placed them in a time-order, and invited scientists to find the serpent halfway in metamorphosis toward being a pteridactyl, the pteridactyl becoming bird. Agassiz stood firm on the unshakable fact that dogs always have puppies; swans, cygnets; snakes, snakes. The Origin of Species was a misnomer. Darwin’s Metamorphoses would have been better, but then Agassiz was a rival poet and fairly soon we may find both on the shelf with Ovid, splendors of imagination.

Interesting thoughts. I always think about the Corpus Hermeticum-assumed for centuries to be the oldest wisdom, now revealed as the syncretic product of the cosmopolitan Alexandrian man in late antiquity-with such ideas The point about Paglia’s horror at the womb and femininity as driver of her sympathy with the crystalline phallic male aesthetic six miles in the sky is a great one and I’ve always thought perhaps the root of her contemporary opposition to the transgender - why would natal males with whom her sympathy resides throw their birthright away OR the androgyny is made too literal, etc. (of course she’s possibly just fucking with us too)