A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I announced this Substack’s new venture in 2024, The Invisible College, a series of literature courses for paid subscribers. The syllabus can be found in the post. I want to thank everyone who has subscribed so far and would like to encourage more to subscribe today. It’s not as if the official institutions are getting any less corrupt—see today’s post below—so you might as well support their current supplementers and future supplanters today. The first lecture, on William Blake, will be released on the 19th of January. I will probably make that one free as an enticement. If you’d like to join us but can’t afford it, email me and I’ll comp you a subscription.

I also published “The Sermon,” the latest chapter of Major Arcana, my serialized novel for paid subscribers, in which Ash del Greco offers dueling theories of Jacob Morrow’s suicide to her YouTube audience in a riven homily about the nature and value of life. This Wednesday comes the delirious and cliff-hanging final chapter of Part Three. The serial continues through February—please subscribe today!

If you missed last week’s Weekly Readings due to holiday festivities or travels, please revisit it today for its review of 2023 and its statement of goals and intentions for 2024, including some important advertisements for myself. In short, I don’t want to write literary criticism this year unless I’m paid in cash or at least exposure under someone else’s marquee. If you want to see criticism from me in 2024, please encourage your friendly neighborhood editor to solicit me.

For today’s post, the first Weekly Reading of the New Year, I look through several different lenses at the current crisis of the universities. Please enjoy!

Poet-Prophet: Against Identity, Against Institutions

A reader writes in to ask, “Lol what’s your take on Chris Ruffo [sic—“Ruffo” sounds like the name of a cartoon dog] claiming anti-Italian discrimination on Twitter?”

In fairness to Rufo, American liberals have been in a state of projective hysteria since the grotesque Trump breached their citadel in 2016, so their endless accusations that so-and-so is a stooge of Russia, China, Israel, etc. can’t but partake of racist scapegoating. I remind you that Richard Spencer and Charles Johnson, stalwarts of the 2016-era alt-right, are now vocal Biden supporters and Democrats, with Richard Hanania not far behind, a shift in alliances that has not required them to alter their racial views very substantially. True reactionaries know the party of power when they see it. (The latter is not, by the way, an endorsement of the party contesting power, which is bad in its own way, as I will soon mention.)

Anyway, I would prefer to answer this question indirectly—or to answer its subtext rather than its text. My very polite audience often seems to inquire in a roundabout way why my tastes, interests, and allegiances can seem so difficult to deduce from the obvious facts of my identity. For the most part, you will have to scrutinize the entirety of my life’s work with exceeding care if you really want to know, but sometimes I give a cogently brief response. Almost exactly a year ago, I answered the queer question, so let me now answer the Italian question.

Instead of producing a new text, however, I will instead use the time-honored academic technique of self-plagiarism and repost something I wrote on Tumblr over two years ago, which most of you, I trust, have not read. It begins as a response to an inquiry on Twitter by the now-controversial editor Park MacDougald about why certain political constituencies—I think he meant the dirtbag left—seem so obsessed with Italian jokes. Then my piece becomes a more wide-ranging reflection on Italian-American identity and literature, such as they are, or rather, why they are impossible. I enclose the repost in gray dividing lines, after which a commentary on Rufo continues.

Well, speaking from my lived experience—no, wait, sorry, I don’t believe in that shit; I speak from passion and intellect, as should you. Anyway, the question is answered several times in the thread: a multi-ethnic and multi-racial society without ethnic and racial humor to relieve tension (“He laughed to free his mind from his mind’s bondage” [James Joyce]) is such a disastrous prescription it could only have been dreamed up by academics, bureaucrats, and corporate managers. Such postmodern padroni don’t ride the public bus—there’s a lived experience!—so they don’t know how this works in everyday life for people who aren’t boxed up in cubicles, and consequently they inflict on the rest of us illiberal, inhumane theories like the “microagression” (as if life consisted of anything else for anybody: “We came here to be insulted” [Philip Roth]). Such concepts are unethical because unlivable, as proved by the discharge of indestructible energy elsewhere, in this case onto the swarthy and greasy person of the wop, the dago—in short, myself and, albeit honorarily, Donald Trump. We’ve earned our punishment, the (critical race) theory goes, because even the people on the public bus understand how, at the border of whiteness (“Garibaldi didn’t unite Italy, he divided Africa” [apocryphal]; “Your hair’s kinkier than mine, Pino” [Spike Lee]), we hypercorrected. As I’ve written:

Please bear in mind, in the matter of identity politics, that DeLillo is the only great American novelist to share my and my family’s ethno-religious and class background. But neither he nor I make heavy weather out of it. It’s nothing, in the literary world, to be proud of. We were the first of the white ethnics to make the break with the left, and we made it more thoroughly than anyone else. As I detailed in my piece on White Noise, as Bill Clinton was the first black president and Barack Obama the first gay president, Donald Trump is the first Italian-American president.

As I said to an Irish-American the other day, however, is it Italian-Americans’ fault if we belong to what once was a minority group but which the political left never got around to creating a redemptive positive identity for? Did we have any choice except to opt for what is tendentiously called assimilationism (a postcolonial scholar once looked me up and down and said to me, “You know, you dark whites will never really assimilate”) but which might better be called universalism? Hence the name of the book: not American Catholica or, still worse, American Italiana, but, and without qualification, Americana. David Bell says, “I wanted to become an artist, as I believed them to be, an individual willing to deal in the complexities of truth.” Amen.

There are only two great Italian-American writers: DeLillo and Paglia. No special pleading for minor beatniks and dreary proletarian novelists, please. Marianna De Marco Torgovnick has made a heroic effort on behalf of The Godfather, but I like her essay better than the book, which—lived experience!—I first read when I was 10. Gay Talese says we’re a visual people and better at movies; I reject this kind of thinking, for my fancied ancestral non-ancestor, the fascist priest Ermenegildo Pistelli, author of Le pistole d'Omero, a paronomasiac play on our shared surname equating letters and guns—I am also descended from stone-cold killers—was a philologist.

Both DeLillo and Paglia identify somewhat more with Catholicism than Italianness per se—which I understand, as someone who doesn’t identify with Italianness at all. A parochial schoolboy in almost the first suburb beyond the city, I was raised less in an Italian milieu, despite the language being spoken around me in my grandmother’s house, than in a multi-ethnic world of immigrants’ children or grandchildren, including Irish, Polish, Lithuanian, German, Vietnamese and other ethnicities in addition to Italian, a world whose two religions were Catholicism and America. Cosmopolites, DeLillo and Paglia rejected identity politics, wrote big universal books, and, when they got to the great world of culture, tended to affiliate with “Jewish utopianism,” itself perfectly congruent with the religion of America.

Have I followed this path? Reader, I saw no other. Ethnic particularism, self-minoritization, is a dead end, also a betrayal of the very people who, in living memory, worked very hard to get us here—out of the village and into the universe (“We must believe that the universe is our birthright” [Jorge Luis Borges]; most Pistellis, I note, are Argentine).

To the woke humorists slinging spicy-meatball quips because they can’t say in public the lines they repeat in private about every other racial and ethnic and sexual minority—and it’s admittedly a rich field, considering only how the major personae of the pandemic are Italian: Cuomo, DeSantis, Fauci—I say: I can take a particularist joke, but can you take the universalist truth?

But the occasion for discussing Ruffo at all today—seriously, a webcomic about Ruffo the right-wing dog could be a hit: imagine his humorous tussles with his feline adversary, Herbert Meowcuse—is the escalation of his war on elite academe.

Following his successful coup against the president of Harvard, he and his newfound allies, among them disaffected rich ex-liberals, promise to raze the Ivy League with AI-powered plagiarism detection. The response by his targets has been so contemptible—I mean this both ways: contemptuous in themselves and inspiring contempt in others—that it’s difficult not to take a bit of pleasure in whatever comeuppance the conservatives are able to deal out.

This feckless elite is so swollen with pride and empty of achievement that one doesn’t wish to defend them, especially if one—in this case, I mean me—has ever been the object of their unearned sense of superiority.1

Rufo has also released “A Manifesto for the Counterrevolution” this week, however. Its avowed goal is to capture the university from its present stewards, who have directed it toward their political purposes, and redirect it toward new political purposes. And not just the university either, as Rufo also promises to “reorient the state toward rightful ends.” Rufo is a right-Gramscian, an illiberal for whom liberalism’s dream of neutral institutions is a cover for the liberal class’s will-to-power, with the corollary that harnessing the same institutions for a conservative will-to-power is perfectly legitimate turnabout. Presumably, he would have found an ally in the fascist priest Ermenegildo Pistelli. Revolution and counterrevolution, then: nothing but spinning our wheels.

Something like this insight led a critic whom I have jokingly designated a foe of this blog to post “a plague on both their houses” about Rufo and his enemies. I deliberately began the New Year on Tumblr by reposting this curse to amplify and agree with it. I hoped to signal a year in which the literary guild as a whole would drop its noxious 2010s delusion about serving as allies and activists on the right side of history, instead understand its place as imaginative beacon for an asymptotic utopia by nature unrealizable as an earthly politics, and band together against the liberal class and the conservative class with their shared desire to instrumentalize art and education. Our critic, however, who appears to be more and more ideologically cross-pressured, deleted his post, and so I deleted mine. The dream, however, persists.

One way to realize this dream is to stigmatize those who view art solely as the product of society, of social forces, of social positions or social identities. Such a view grants authority over art not to artists but to prevailing social forces—and ultimately to the state, whether under left, right, or centrist control.

For example: during Rufo’s first attack on President Gay, an academic strangely stepped up to support Gay by accusing a prominent literary critic and theorist of plagiarism, on the theory that, if this white man went unpunished, only racism and sexism could explain the punishment of Gay. Whether or not the accused academic did steal his ideas, I couldn’t help but note that profound irony that his own theory holds as an article of faith that literary works are not the work of the individual. At an earlier moment in the expert class’s convergence upon an empowering “progressive” anti-humanist agenda, the unnamed scholar hastened this very convergence with his influential contention that the works of Shakespeare were written by, and I quote, “social energy.” Such energy, goes the implication, requires for its proper direction and maintenance not the errant inventiveness of men from Stratford but rather the credentialed expertise of men from Harvard. Too bad he couldn’t have (allegedly!) stolen a better idea. Then again, not being private property, how can such ideas be stolen?2

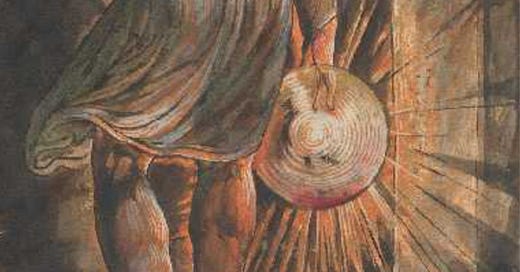

I’ve been reading Northrop Frye’s Fearful Symmetry: A Study of William Blake for the past week to prepare for my own course offering on the great poet.3 Blake believed great art to come from the inspired individual, the poet-prophet, speaking with the voice of God.4 It was not, therefore, the product of individual intention. Every individual has intentions, but not every individual produces great art even when intending to do so, and no individual produces great art all the time, though some manage to produce it sometime. The individual is not the sole source of art, then, but Blake still understood that artists require an absolute freedom from social and governmental control, both to achieve prophecy in the first place, without public interference, and to have their prophecies heeded by institutions they ought to lead rather than to follow. Here is Frye glossing Milton’s Areopagitica in Blake’s spirit:

The greatness of Areopagitica is that it speaks for liberty, not tolerance: it is not the plea of a nervous intellectual who hopes that a brutal majority will at least leave him alone, but a demand for the release of creative power and a vision of an imaginative culture in which the genius is not an intellectual so much as a prophet and seer. The release of creative genius is the only social problem that matters, for such a release is not the granting of extra privileges to a small class, but the unbinding of a Titan in man who will soon begin to tear down the sun and moon and enter Paradise. The creative impulse in man is God in man; the work of art, or the good book, is an image of God, and to kill it is to put out the perceiving eye of God.

This is the view I would like to see prevail in America. In comparison to this idealism, in matters little which band of “priests in black gowns” propose to control art through the institutions. It mattered more, however, back when the left side of the sociopolitical field considered itself the heir to Blake rather than the heir to Gramsci.5 Maybe this, too, can be restored to us in the New Year.

Twice in graduate school at the University of Minnesota, my professors paused in their seminars to explain to us, their students at the University of Minnesota, why they themselves were forced to teach in so inadequate a school as the University of Minnesota—a state school; one vomits—given their own Ivy League pedigrees (Columbia and Yale, if you’re wondering). The one said it was because he was a white expert in non-white literatures in a time when hiring lines for specialists in non-white literatures were tacitly reserved for non-white scholars. This at least had the virtue of bold honesty, however unpleasant. The other said it was because he was too smart. “Who will check his work?” he quoted a member of the hiring committee that rejected him from an elite school. What inspired the committee member’s helpless prostration before his awesome intellect? His observation that Auerbach’s Mimesis ends with “The Brown Stocking” to symbolically cover Odysseus’s injured leg of the famous first chapter, “Odysseus’ Scar,” thus circling the book back in on itself with the adventure of western representation ending as it began in frozen clarity, whether Homer’s representation of exteriors or Woolf’s of the inner life. A fine observation, to be sure, but too good for the Ivies? I guess I wouldn’t know, would I?

I am in fact puzzled by the zeal my colleagues often show in hunting down plagiarism by students given their own theoretical commitments.

Isn’t it a bit absurd for academics in the field of literary studies, which has spent several generations now not only arguing against but positively stigmatizing the idea that individual creativity could be the source of textual production, to get so uptight when their budding author-functions spontaneously concur with Barthes that “a text is made of multiple writings”? Now I doggedly suspect that individual creativity, at least as it channels the oversoul, might really be the font of good writing and good art, and I suspect, moreover, that the other way of thinking (i.e., Barthes/Foucault), which sounded so emancipatory in its time, actually heralded new forms of control. A wise Marxist once contended, on a now-defunct website, that such avant-garde artworks as Duchamp’s Fountain and Cage’s 4’33’’ were models for corporate proprietorship, enclosing and capitalizing other people’s material labor (in Duchamp’s case) or other people’s very being and presence (in Cage’s) as the corporate monopolies would come to enclose and capitalize more and more of our common life—as, for instance, the papers students submit to their instructors for grading, now processed and analyzed by for-profit companies that license surveillance software to schools.

(The paragraph above is self-plagiarized, with a few emendations, from another old Tumblr post of mine. As Harold Bloom says somewhere, plagiarism is a legal category, not an aesthetic one—and no one except perhaps Žižek has self-plagiarized as much as Bloom has, those two being less author-functions than author-factories. You can search my dissertation, though, even with AI; I believe it is entirely free of that crime, even in the voguish interchapter on “affect theory,” which I thought was kind of stupid even at the time. There, I didn’t really feel like explaining Spinoza’s enervating theory of the emotions, so I supplied a fully credited almost page-long block quotation from a secondary source—a gauche practice, no doubt, but a licit one. Spinoza with his geometric style and his detached monism depresses my will to live and is thus evil on the terms of his own theory. Here’s a lecture from an old commie prof of mine unfavorably contrasting Spinoza with Vico. Except that this commie thinks Vico’s tradition legitimately issues in Lenin rather than in Joyce, I tend to agree. So much for my “scholarship.” Now my fiction is full of unattributed quotations, but those are allusions, not plagiarisms, and I intend for you to recognize them.)

What I really want to do is type the whole book into here and comment on it line by line. It’s an extraordinary work of criticism; I can’t recommend it more highly. You don’t even have to read Blake’s prophetic books first, as Frye’s study serves as much as an introduction as an an explication after the fact (Milton and Jerusalem are basically unreadable without such a guide). I will reserve most of my comments on Fearful Symmetry, however, for my forthcoming lecture on Blake.

Intriguingly, the counterattack in the plagiarism war came when Rufo’s enemies accused Neri Oxman, the wife of one of his allies, of plagiarizing her dissertation. I just learned who Oxman was a few months ago when the YouTube algorithm served me a video in which she explained her views on manifestation to Lex Fridman. (I’ve had to watch lot of manifestation videos to write the Ash del Greco chapters of Major Arcana.) Her design practice of bio-art, subtended by the Shakespearean view that the art itself is nature, is probably too caught up for Blake in nature itself, trapped in what he would call “Beulah” and “female will,” hence why it’s not impolite to wonder if her cachet comes in part from her striking beauty. I myself am closer to Shakespeare and to Oxman, as witness my censure of the Blakean David Lindsay in April Books. Oxman’s views on manifestation are accordingly pragmatic and this-worldly, while even Frye, despite his tone of mordant sobriety, explains Blake so as to make clear that Neville Goddard wasn’t lying when he said he derived his own practice from the visionary poet:

Nearly all of us have felt, at least in childhood, that if we imagine that a thing is so, it therefore either is so or can be made to become so. All of us have to learn that this almost never happens, or happens only in very limited ways; but the visionary, like the child, continues to believe that it always ought to happen. We are so possessed with the idea of the duty of acceptance that we are inclined to forget our mental birthright, and prudent and sensible people encourage us in this. That is why Blake is so full of aphorisms like “If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise.” Such wisdom is based on the fact that imagination creates reality, and as desire is a part of imagination, the world we desire is more real than the world we passively accept.

(As a footnote to this footnote, insert here an extended commentary on two of my favorite endings in American literature: first, the end of Cynthia Ozick’s The Cannibal Galaxy, where a not-quite-redemptive female artist actually named Beulah produces not-quite-redemptive art, and, in counterpoint, the end of Toni Morrison’s Paradise, where a black goddess appears as the apocalypse Blake describes, except that Morrison, too, remains on the level of what Blake and Ozick would reprehend as the bathetically embowered feminine estate. I’m not going to write this commentary, however, at least not now. Major Arcana is probably the best I can do. While Major Arcana encompasses Athens and Jerusalem in its danse macabre of the del Grecos and the Cohens, it admittedly does not quite extend its global ambit to Africa, as Blake and Morrison do, though Ozick did not either until Antiquities, which geographic expansion will have to wait until my next big book, whatever and whenever that may be.)

The materialist version of revolution is always, as far as Blake is concerned, an inevitably tyrannical corruption of the real thing, the replacement of the old regime’s religious obscurantism with nature-worship and dead matter’s reign. One more passage from Frye, since I can’t help myself; please note the similarity between Frye/Blake’s critique of Thomas Paine and Daniel Oppenheimer’s recent critique of Noam Chomsky, himself the heir of the 17th-century rationalism Blake bitterly captions as “single vision and Newton’s sleep”:

He met and liked Tom Paine, and respected his honesty as a thinker. Yet Paine could write in his Age of Reason:

I had some turn, and I believe some talent for poetry; but this I rather repressed than encouraged, as leading too much into the field of imagination.

The attitude to life implied by such a remark can have no permanent revolutionary vigor, for underlying it is the weary materialism which asserts that the deader a thing is the more trustworthy it is; that a rock is a solid reality and that the vital spirit of a living man is a rarefied and diaphanous ghost. It is no accident that Paine should say in the same book that God can be revealed only by mechanics, and that a mill is a microcosm of the universe. A revolution based on such ideas is not an awakening of the spirit of man: if it kills a tyrant, it can only replace him with another, as the French Revolution swung from Bourbon to Bonaparte. And if it abolishes tyrants altogether, it can only do so by establishing a tyranny of custom so powerful that the tyrant will not be necessary, as in the ant-republic. An inadequate mental attitude to liberty can think of it only as a leveling-out.

lol: "Spinoza with his geometric style and his detached monism depresses my will to live and is thus evil on the terms of his own theory. "

Frye's Fearful Symmetry is such a masterpiece one almost weeps thinking of it.

Idk if you'd have seen my essay on Rufo this summer (https://americanaffairsjournal.org/2023/08/the-long-march-of-the-anti-woke-and-its-uncertain-destination/)--not sure there can ever be enough contempt for him! Watching the footage of him speaking at New College is really stomach turning: Heidegger's rectoral address retarded-redux