A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I published “Sweet Humanity,” the latest chapter of Major Arcana, my serialized novel for paid subscribers. The novel is now almost entirely complete. I have about 1000 words left to write, and I have Part Four to get into shape on the sentence level, but the narrative is effectively finished, with Simon Magnus, Ash del Greco, and the rest conveyed to their final fates. The serial will conclude, according to my never-very-reliable calculations, on February 28, 2024. In either my final Sunday post of this year or my first of the next, I will announce what weekly amenities paid subscribers can expect following the serial. Thanks to those who have been reading along. A print edition will follow the serialization pretty quickly, but I don’t have a date appointed yet. Please subscribe today!

For today’s post, a topical three-parter. First, some thoughts on a recent article about magic and manifestation in the light of Major Arcana; second, my non-statement statement on the recent controversy about Substack moderation; third, a postscript on doctoral dissertations in the news, with some thoughts about my own decade-old diss. Please enjoy!

From Below: Magic and the Modern

Tara Isabella Burton’s most recent article, “Of Memes and Magick,” provides a timely gloss on the manifestation magic my novel has dramatized.

Burton’s is a useful historical primer showing that the modern itself—modern politics, to include the American founding; modern science, beginning in the Renaissance; and, though she doesn’t mention it as much, modern literature, from The Faerie Queene and The Tempest forward—cannot be dissociated from magic.

From context clues here and elsewhere, I understand Burton to be a Catholic liberal or social democrat, and therefore one who wants to stuff the diffusion of this once-elitist esotericism, a diffusion now encompassing everyone from Trump to TikTok witches, back inside its genie bottle. [Erratum: She’s Episcopalian, for which see the comments to this post.] At least aesthetically, if not in a strictly political sense, I may prefer the potentially salutary chaos of both Trump and the TikTok witches over any attempt to re-assert totalizing orthodoxies, whether Catholic or Marxist,1 which the present disposition of communications technology has frankly obsolesced.2 Their affirmations and vision boards might be crass, tasteless, and sometimes selfish, but a real and possibly (I mistrust this word) progressive spiritual intuition, now made available to the mass of technologized humanity though once reserved only for the elite initiate, waits beneath the manifestor’s tinsel.

I wrote “Trump” above for the sake of shock value, but Obama’s first inaugural was bound and sold as a single volume with Emerson’s “Self-Reliance.” Emerson, steeped in Swedenborg and Neoplatonism, meant by “self-reliance” not the rational self-interest of homo economicus but nothing other than what Crowley meant by “love under will.” Both meant the spiritual discipline of finding one’s true will by aligning it with the divine will, what Emerson himself called the “over-soul” or what Hegel (also a Hermeticist) called “the world-spirit.”

That this practice is a spiritual discipline—an “education of desire,” to borrow Allen Mandelbaum’s phrase for the Purgatorio—tells us that it’s not as crass or selfish as it may appear from the outside, though the gurus, from Hegel and Emerson to Trump and the TikTok witches, do differ among themselves about how selfish it should be.3 Even Crowley, the “wickedest man in the world,” insisted that “pure will [is] unassuaged of purpose, delivered from the lust of result”—hardly a counsel to mindless greed.

Modernity, as a time of world-historical adolescence, did tend to give a revolutionary Satanic coloration to the whole concept of magic, however, from Milton’s sympathy for the devil to Joyce’s rebel-angel non serviam. Emerson wrote, in the same essay bound together with Obama’s address,

On my saying, What have I to do with the sacredness of traditions, if I live wholly from within? my friend suggested,—“But these impulses may be from below, not from above.” I replied, “They do not seem to me to be such; but if I am the Devil’s child, I will live then from the Devil.”

—a Satanic credo echoed in the exclamations of some of our literature’s greatest fictional characters, such as Captain Ahab (“Ego non baptizo te in nomine patris, sed in nomine diaboli”), Huckleberry Finn (“All right, then, I’ll go to hell”), and Sula Peace (“Whatever’s burning in me is mine”).

The mature adept, though, knows with Blake not only that the devil’s party is the party of energy but also that everything possible to be believed is an image of the truth, and so outgrows the teenaged scorn of the great religions and comes to an appreciation of their spiritual truth. Wilde’s deathbed conversion—and still more his tender (self-)portrait as/of the artist Christ in De Profundis—means something, or means something, anyway, to me, though it would not have when I myself was a Satanic adolescent. Something more than chaos and vulgarity may come, too, from our own time of meme magick.

Anti-Petition: Free Speech, Free Silence

One of the sorrows of the present—or perhaps of the modern—is how many petitions writers, artists, and intellectuals are always signing. They affix their signatures, they retract their signatures, they find another petition to sign, and so on, ad infinitum and ad nauseam. I ask these authors: isn’t there something you could be writing besides your own name over and over again, as if you were a four-year-old learning to form letters?

I used to sign petitions but no more. The very habit is corrupting. It encourages us to think of our role as something other than it is. The socially redemptive effect of artistic work, if it has one, must be, as George Eliot wrote in a (somewhat) different context, “incalculably diffusive,” my emphasis, and both words are important, rather than directly effectual. I don’t care what the petition is for, I’m not signing it. I won’t even sign your petition against kicking kittens.

I proposed “the modern” above as a source of the problem, in this case literary and intellectual modernity. It’s always tempting to blame the French: over three Gallic centuries, we could say that Voltaire solidifies, Zola codifies, and Sartre ossifies the model of the activist critical intellectual, always at the ready to intervene in any and all public affairs on behalf of universal reason in its long war against superstition, barbarism, and backwardness of every sort: Ecrasez l’infâme!

We often forget that postmodernism, so-called, could easily be understood not as a form of extreme leftism but rather as a moderate or conservative reaction against the Sartrean intellectual’s radical presumption, given universal reason’s 20th-century issuance in death camp, gulag, and A-bomb; Lyotard and Foucault, to name only two, were fairly explicit about this motive for their own work.

But this quarrel was held earlier, and in English, too, its recurrence in many places and periods itself apparently a feature of the modern. I mentioned last week that I’m currently reading The Last Man by Mary Shelley. In that strange, flawed, vast, boring, horrifying, prescient, somber, and beautiful novel of 1826, Shelley continues the loving quarrel with Romantic radicalism she broached in the more famous Frankenstein—all the more poignant given that she wrote the novel after the deaths both of Percy and of Byron, and she places them, lightly disguised, in her futuristic romance, as the characters Adrian and Raymond, respectively.

Imagining a Greece still under the Ottoman yoke in her invented late 21st century, Shelley’s narrator explains why the aristocratic rebel Raymond, the novel’s Byron stand-in, wants to liberate the cradle of western reason from its “Oriental” subjection:

He wished to repay the kindness of the Athenians, to keep alive the splendid associations connected with his name, and to eradicate from Europe a power which, while every other nation advanced in civilization, stood still, a monument of antique barbarism

As I’ve discussed here before in recent months, we were given Edward Said to read when we were young, so we can immediately think of several political objections to this kind of rhetoric. But Shelley’s Percy stand-in, the beautiful soul Adrian, who in this fiction joins Raymond in fighting for Greece and thus witnesses the war, as Percy in fact did not, movingly expresses a more basic human objection:

“It is well,” said Adrian, “to prate of war in these pleasant shades, and with much ill-spent oil make a show of joy, because many thousand of our fellow-creatures leave with pain this sweet air and natal earth. I shall not be suspected of being averse to the Greek cause; I know and feel its necessity; it is beyond every other a good cause. I have defended it with my sword, and was willing that my spirit should be breathed out in its defence; freedom is of more worth than life, and the Greeks do well to defend their privilege unto death. But let us not deceive ourselves. The Turks are men; each fibre, each limb is as feeling as our own, and every spasm, be it mental or bodily, is as truly felt in a Turk’s heart or brain, as in a Greek’s. The last action at which I was present was the taking of ——. The Turks resisted to the last, the garrison perished on the ramparts, and we entered by assault. Every breathing creature within the walls was massacred. Think you, amidst the shrieks of violated innocence and helpless infancy, I did not feel in every nerve the cry of a fellow being? They were men and women, the sufferers, before they were Mahometans, and when they rise turbanless from the grave, in what except their good or evil actions will they be the better or worse than we?”

It is a very English and a very feminine and a very middle-class gesture, you will say along with friend-of-the-blog Nancy Armstrong, meant as a private balm offered by ladies and artists to treat and to complement the brutal jostle for power and pelf of public man, the aforementioned and inartistic homo economicus. Our ladies and artists refuse to ground the basis of universal human freedom in the universality of human reason, searching instead for the basis of universal human peace in the universality of human feeling. As I tried to show in a certain document I’ll be discussing below, however, this intuition can also be found at the root of the aesthetic as such, and of aestheticism, of the idea that art should and must be apolitical: that writers must not sign petitions.

The radical activist intellectual, scoffing, will say, “But that’s the most political position of all!” To which I rejoin: “Yes, dummy, we know! You’re the one who doesn’t recognize your own politics when restated in an idiom that has half of chance of actually working instead of killing everybody in sight and making everybody who’s still standing disgusted with the whole idea!”4

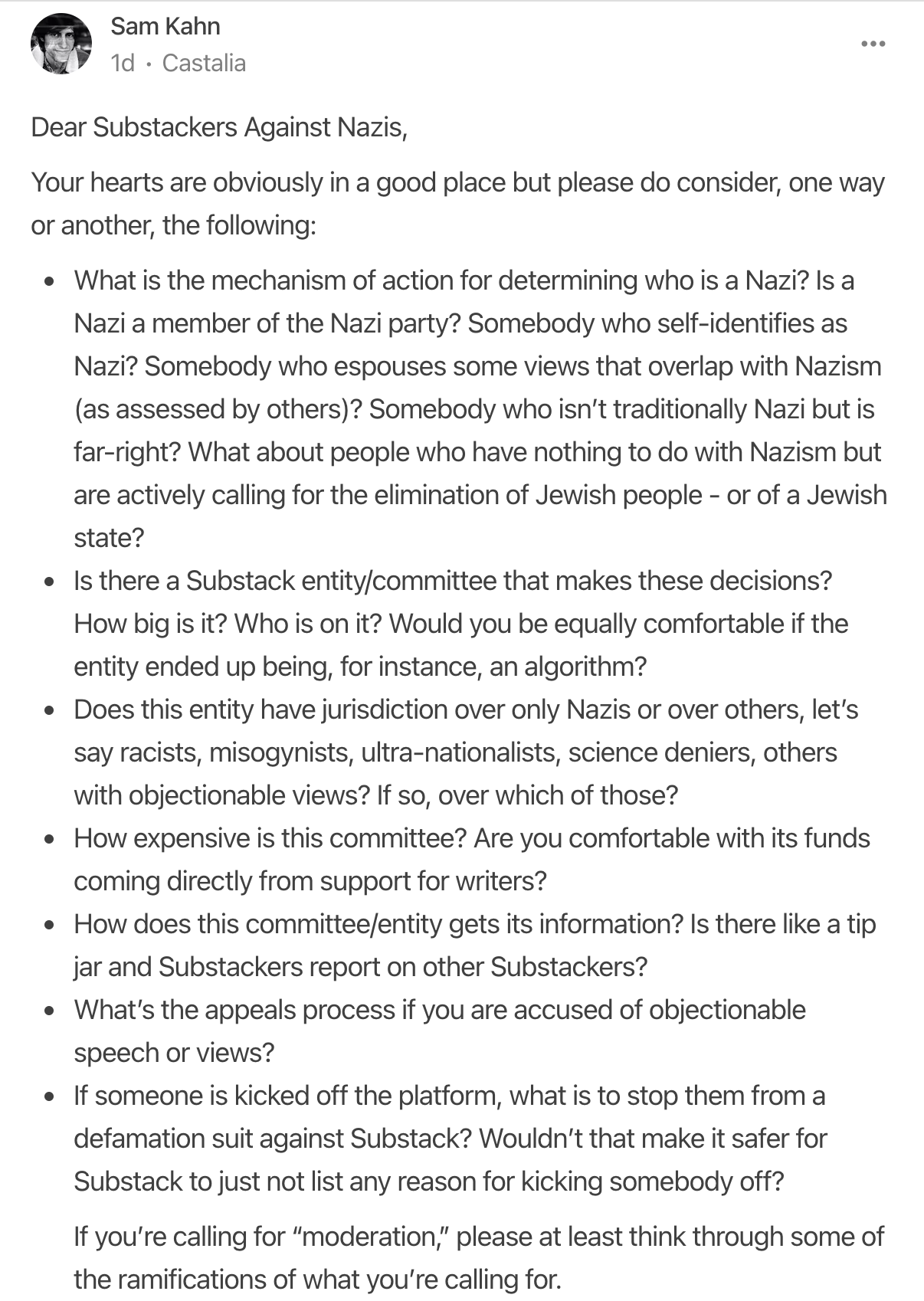

These are old quarrels, however. I meant to address a new quarrel here, namely, the dueling petitions launched this week on Substack itself. One called for the kind of heavy-handed content moderation that has been the bane of other platforms with the usual invocations of “Nazis” and “hate speech” and “misinformation,” while the other called instead for the present laissez-faire policy to continue.

Needless to say, I support the latter position. Free speech is not a government policy but a culture. Mill dispatched the tired argument that freedom of speech only means protection from government censorship back in the 19th century. He argued in On Liberty that the concept was meaningless if it did not also include protection from public opinion and economic interference:

In respect to all persons but those whose pecuniary circumstances make them independent of the good will of other people, opinion, on this subject, is as efficacious as law; men might as well be imprisoned, as excluded from the means of earning their bread.

Part of a culture of freedom is learning how to deal with speech one loathes in ways more creative, intelligent, and constructive—and therefore more effective—than calling it by imprecise fear-names meant to trigger its bureaucratic suppression.5

The anti-free-speech petition exemplifies this strategic imprecision when it invokes, almost a decade too late, Richard Spencer as its Nazi figurehead. Such a mistake is symptomatic of the problem with trying to regulate speech and (therefore) thought in this way. Spencer has been for years now a supporter of Biden and NATO. He pragmatically judges today’s elite Democratic Party left-liberalism, with its loathing of “dysgenic” Trumpist populism, its “eugenic” commitment to family planning of all sorts, its foreign policy aimed against the “Oriental despotism” of Russia and China, and its increasing hostility to the state of Israel and its so-called “interference” in our own politics, to be more in line with his views than is the nationalism or libertarianism of the American right. Present-day Richard Spencer has far more in common with Rachel Maddow than with Nick Fuentes. (Present-day Spencer himself uses “Nazi” as an epithet!) Actually crafting a policy to suppress Spencer’s speech in 2023 will have to silence plenty of other people, including the many conventional liberals who share his views.

The would-be censors are probably undisturbed by that possibility. In my experience, they believe that “error has no rights,” and they are further convinced (is there any greater arrogance or delusion?) that only their perfectly well-informed and non-hateful ideas should be permitted utterance. But for anybody who might ever say anything that transgresses the very narrow ideological hegemony proposed by those who hold strong ideas about what constitutes “hate” and “misinformation,” the idea can only be terrifying.6

So why shouldn’t I sign the petition for preserving free speech on Substack? Even apolitical Chekhov said the artist should engage in as much politics as protects the writer from politics, and defending free speech surely qualifies. I don’t sign it because I want to preserve the right not to engage, a freedom that can only be grounded in the Romantic counter-Romantic model of human solidarity beneath the political expressed in Adrian/Shelley’s humanist speech as given above in The Last Man, rather than in an Enlightenment-style right to speak truth. I don’t sign because silence may exemplify freedom of speech in its highest form. Substack, however, should absolutely resist these calls for censorship and censoriousness.

Postscriptum: Diss-topia

Doctoral dissertations, strangely, have been in the news recently. First, there was the new right guru’s self-published and yellow-bound diss on ancient poetry and philosophy as a testament to “selective breeding,” which surprisingly cracked Amazon’s top 100 and received reviews by eminent thinkers in high places. Now we hear some allegations—I have not personally examined the evidence; I render no verdict—about the president of Harvard’s dissertation.7

It’s a strange genre, the doctoral dissertation. No one expects them to be excellent. Veteran academics tell their young charges, before they send them out into the jobless wastes, “There are only two kinds of dissertations: finished and unfinished.” As a scorner of the immobilizing Flaubertian perfectionism, this is actually my attitude toward writing books tout court. I don’t think I’ve ever drafted a book, whether my circa-90K-word doctoral dissertation to the circa-160K-word Major Arcana, in over about six months. I work in bursts of inspiration, so this “six months” may be continuous (it was with Portraits and Ashes and Major Arcana) or may be spread out over a couple of years (as with my dissertation and with The Class of 2000), but “slow and steady” was never my way. You lose a bit of precision with this method, I’ll allow, but you gain momentum, both for yourself and for the reader. It’s indecent to repeat praise, but one of my committee members told me that he’d set aside a week to read my completed dissertation at the dutiful rate of a chapter a day, but when he picked it up, he couldn’t stop reading and finished it in a night. My advisor likewise paid it the highest compliment the littérateur ever grants a work of nonfiction: “reads like a novel.”

Even though my dissertation reads like a novel, however, and even though it may be read as a kind of inadvertent rejoinder to BAP’s—elevating the moderns over the ancients, selective memetics over selective genetics—I am probably too lazy to self-publish it in any form other than the one you can already read. Formatting those footnotes was annoying enough the first time; I don’t want to do it again. But I do want to remind older readers and inform newer readers that it is freely available if you’re interested. The university that granted me the degree hosts it here, but I’ll leave it in this post, too, in case they ever change their mind.

As I’ve said and will here repeat, there are also true things contained in Catholicism and in Marxism—the spiritualized sensuality and respect for female divinity in the former, the intellectual methods of dialectics and immanent critique in the latter—but these are best teased apart from the two ideologies’ shared bureaucratic-totalitarian tendency and wedded instead to the otherwise too absolutist and and too masculinist Protestant-gnostic individualism of Emerson, Nietzsche, and Crowley. Again, however, this is all best dramatized in my fiction, not articulated in abstract prose, which I am in any case not qualified to write.

I do note that among the most influential Trump supporters on YouTube is an ex-Satanist and currently practicing occultist who edits magical texts and continues to advocate magic in among his political videos, for which see here. Also an ex-liberal of libertarian bent, he’s always wryly reading out messages from his Christian conservative watchers stating that they’ll pray for his soul, when he’s not fending off their hostility to his pro-choice, pro-gay-marriage, and even (at least relative to his milieu) not especially anti-trans social views—do what thou wilt being, of course, the whole of the law.

If I were the piece’s editor, I might have suggested that Burton show a more detailed awareness of just this distinction among today’s manifestation gurus: those advocating manifestation as technical process (repeating affirmations) for acquiring largely material goods (sex, status, money) vs. those, usually pledged to some spiritual tradition, who stress by contrast the “education of desire” part of the process, the sense that you are here not to gain mere things (those “qlippoth” spoken of by the Kabbalists) but to discover and become who you are, the god within. Such divides often hint at religious, class, and racial divisions that would complicate any cheap political argument here—the “get your mans, get your bag” side, though it codes as “right-wing,” tends to be more working-class and more racially diverse than the liberal yoga-mat matcha-latte “raise your vibration” side.

This is what I meant when I wrote earlier this year, in a post about a lot of things but mainly about 2666, a perhaps otherwise obscure sentence that may be the most important sentence I wrote outside of Major Arcana in 2023: “It’s not just that writers should be permitted to descend from Kafka as well as from Dickens, it’s that Kafka also descends from Dickens.”

I shouldn’t even have to point this out, but calling everybody and everything “Nazi” and “fascist” is an old tactic of left-totalitarianism. “We can’t be bad because we’re anti-fascist!” is the alibi of Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot—the prelude to many a massacre and a book-burning.

Substack grew to prominence, we are apparently now forgetting, as a place for counter-hegemonic speech about the disastrous state and corporate coercions of the pandemic era, from the curtailment of inquiry into the virus’s origin to the banning of democratic discourse about whether or not the most powerful forces in our society ought to have the right to impose upon our bodies, at what was tantamount to gunpoint, the experimental products of the pharmaceutical corporations.

An academic said on X that if all dissertations were scrutinized, many would be found to contain similar levels of (alleged) plagiarism as Gay’s. I wonder. As a scholar, such as I am, I believe I have the opposite problem: hasty reading and tendentious paraphrase rather than any kind of copying. Then again, plagiarism may afflict the more fact-based disciplines more severely. My dissertation, an interpretive and theoretical exercise, promises no original research and contains, I hope, not a single fact. With one of my dissertation’s subjects, Wilde, I look askance on “careless habits of accuracy.” Speaking of Wilde, I suppose I did do a sole piece of original research for my diss, which you can find, if you care, on pages 88-89. I wasn’t the only person ever to look at that particular archival document—it’s even been published in a popular edition—but I believe I brought a question to the text no one had quite asked of it before. So there: I’ve done one scholarly thing in my life!

We ought to start more weeks with three-parter essays as varied as this one, honestly.

It turns out that Burton is Episcopalian (per an interview about modern self-invention with Plough Magazine, if I recall correctly). Since it's a Protestant sister-denomination with Catholicism, where would you put her / her tradition between the Catholic "spiritualized sensuality and respect for female divinity" and the Protestant "too absolutist and and too masculinist Protestant-gnostic individualism"? It's not exactly the Protestant tradition where I worship, but it does have its own beautiful aesthetics and intellectual history on its own.

Here's that interview: https://open.spotify.com/episode/6PdsbXJc7nhamG24u7KGUp?si=5bfa1cb4bf1c4776

Good thoughts. It’s sorta interesting that substack is becoming mainstream and I suppose centrist enough to *have* these debates, considering that for a long time it was perceived as “the site for people who think Covid and racism aren’t real and trans women are men.” It’s still pretty right wing (occasionally I’ll look at a subscriber and think “you follow *me*???” although I should say I’ve yet to see any nazis myself.