A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I primarily want to remind you of The Invisible College’s imminent return on Friday with an episode on Homer’s Odyssey. (The Invisible College is my series of literature courses—i.e., it’s a podcast—for paid subscribers; the introduction to the whole project and the 2024 schedule is here, the introduction to the 2025 schedule here.) If you offer a paid subscription now, you probably won’t have time to listen before Friday to the entire 2024 archive, including episodes on major poets (Blake, Keats, Whitman, Dickinson, Yeats, Stevens, and more) and great novels (Pride and Prejudice, Moby-Dick, Middlemarch, Ulysses, To the Lighthouse, and more) of the English language from Romanticism to modernism, but it will give you plenty of audio for the whole winter. This year, we expand our remit to include ancient Greek, modern European, and English Renaissance1 literature in winter, spring, and summer before returning to the 19th and 20th centuries for a survey of the American novel in the fall, encompassing everyone from Homer to Shakespeare to Toni Morrison. Thanks to all my current and future paid subscribers!

My novel, Major Arcana, is also coming out in a little over three months, on April 22, the day after Shakespeare’s birthday. This epic of an American Faust tells the story of an occultist comic-book writer of the late 20th century whose cultural and familial influence reaches into the present day and proves transformative—of language, gender, the body, the soul, and the very meaning of life, love, and death—for several generations. Publishing runs on pre-orders, so if you’d like to encourage more writers and more presses to take a chance on strange, ambitious novels,2 you can pre-order Major Arcana here. If you can’t wait, a paid subscription purchases you access to the original Substack serial, including my audio rendition of each chapter.

For today, I repost from my super-secret Tumblr, with added links and footnotes, some recent discourse on criticism across the arts and the pleasures and dangers of a supra-criticism. Please enjoy!

Supra-Criticism: Totalizing the Arts

A reader recently wrote in to my super-secret Tumblr to inquire as follows:

do you have recs for critics who can write equally well about multiple domains of art? films and literature, music and photography, games and painting—that sort of thing. I was reading some old lrbs (i let them pile up unread for years and now am getting rid of them) and found multiple issues with exhibition/gallery reviews by established literati, usually novelists and poets. they were well-written “at the sentence level” but very superficial otherwise. pleasant enough to read but said nothing that stuck with you. i can understand why that’s the case, but it made me wonder which writers/critics actually could span the arts3

I replied: I’ve basically given up the legacy publications, because you can’t get three paragraphs into something before the writer has dropped some thought-terminating cliche (“late capitalism,” “anthropocene,” “patriarchy”)4 that either stands between the critic and the work or is (even worse!) actually the substance of the work. So, in short, not really. Of the older guard, I used to like Lawrence Weschler, a bit wide-eyed in the New Sincere style of the era in which he flourished, but pretty interesting in his way, and Daniel Mendelsohn, very tasteful, able to bring his genuine classicist’s erudition to bear on contemporary film, TV, pop fiction, even as he also writes well about the classics themselves. Jed Perl’s last book, encompassing Anni Albers and Aretha Franklin and Virginia Woolf and many more, was really good. The late Clive James, Cultural Amnesia. On the countercultural side, Howard Hampton (see his collection Born in Flames) is a worthy heir to that style of earlier 20th-century wide-ranging rebel criticism he cites ranging from Benjamin all the way to Kael.5

To invoke Benjamin, however, is to be reminded that the canonical critics who easily ranged across the arts in the 19th and 20th centuries (Hegel, Nietzsche; Ruskin, Pater; Adorno, Barthes; Sontag, Jameson) became something more than art critics—rose in fact to become critics of the culture at large, or of the very idea of culture, supra-critics of the code sub-writing every instance of an artwork, figures able to challenge the authority of artists themselves as exegetes and redeemers of reality itself.6 And critics today attempt to conjure this authority with their cheap and easy citations of phrases that long ago lost their meaning and force, such as “late capitalism,” but the erudition backing the currency of the supra-critic’s discourse seems largely to have been debased, along with the culture itself.

Or so I say in my own culture-critic mode; but perhaps the pursuit of this Hegelian absolute consciousness was always a mistake—perhaps it is better just to make art than to try to become its master in surveilling it totally—and so who cares if New Yorker writers or YouTube video essayists are not exactly Hegel or Sontag?

From a recent post on X:

Paglia makes the point that renaming the Renaissance the Early Modern period is a downgrade—a beautifully descriptive name traded for a characterless one. (Also Dark Ages to Middle Ages.) Shows the academic abandonment of broad, expressive strokes for mincing little exceptions

I always forget what I wrote in these Weekly Readings, but recently recalled how, when I first self-published Major Arcana, before it was adopted by the distinguished Belt Publishing, I wrote a long footnote—attached to a rather brash essay on race and ethnicity in the American novel!—imagining all the good and bad reviews it might receive from various literary luminaries. Now that Major Arcana actually is circulating among reviewers, though maybe not all those I named, I thought it might be funny to repost this for my many new subscribers. I wrote:

A good postmodern stunt would be for me to imagine and then to produce excerpts of various prominent critics’ and venues’ reviews of the novel. Luckily for you, I would never do such a thing. I would never imagine, for example, James Wood’s admiration in the New Yorker for the novel’s closely observed realist texture combined with his censure of its magical preoccupation and indeed magical events, as these threaten to undermine fiction’s secular ethical basis of sympathetic imagination, which should be magic enough for us. I wouldn’t dare imagine Christian Lorentzen’s wary approval in the Financial Times of the book’s ambitious scope and DeLillo-esque episodes of gritty paranoia and vertiginous present-day Futurism, nor his rebuke of its culminating Millennial sincerity. Why would I imagine Ryan Ruby in the New Left Review holding up as specimens of failure the novel’s less ambitious sentences on his way to a wholesale indictment of its “neoliberal” conception of a world (or at least an America) where we must save ourselves through magic means or otherwise, since no one else is coming to save us? Or Valerie Stivers in Compact, with her appreciation of the novel’s metaphysical ambition and warm-hearted humanism, even as she balks at its credulity in the face of the occult and its final unwillingness to dismiss the charlatan magician in favor of the authentic priest? Or Andrea Long Chu in New York repudiating every last inch of the novel, from its superannuated realism of form to its obscurantist fantasy of content, from its “centrist” hesitation before the final frontier of gender medicine to its (again!) “neoliberal” skepticism about state and society as redemptive agencies? I wouldn’t dream of the way Parul Sehgal in the New York Times nervously credits the novel’s unfashionable ambition, complexity of plot, and depth of characterization, even as she wonder where it finally does come down on the question of gender it so urgently raises and what implication this has for our polarized political culture in an election year. Why imagine Zero HP Lovecraft in his debut as a Mars Review of Books author appreciating the novel’s several passages of cosmic horror but finally dismissing the whole thing as a sickening woke farrago ridiculously sympathetic to its hysterical heroines and utterly feminized male protagonists? No, I’d imagine no such thing—we all know serious authors never dream of publicity!

Perhaps testing my own abilities in this area, another anon then shortly asked me to review Perverts, the recent reputedly “terrifying” release by Ethel Cain. I replied:

I respect it. I believe I understand what motivated it. The desire to go deeper into the most alien and alienating possibilities of your chosen art’s form; the desire to explore more unsparingly the least social or salubrious sources of your inspiration; the desire to wrong-foot a fandom that thinks it knows you too well; the desire to repulse a popular audience that translates your work into pabulum. Astringency of form and content to abrade the social order in the complacency of its damage: just what Dr. Adorno ordered, except that Adorno wasn’t quite imagining (what I take to be the psycho-sexual theme here, signaled by paratextual recollections of masturbating to Brutalist architecture in Coraopolis, about 15 miles from where I now type) the sublimation of the perverse into an eros de-fixated on the vulnerable corpus of the pervert’s potential victim and cathected onto, well, the sublime. Nearer my God to thee, indeed: “Heaven has forsaken the masturbator / It’s happening to everybody.” Thus masturbate to or at heaven. What does the drone “pull”? Drone music as goon accompaniment, gnostic-tantric plateau of ecstasy, sustained vibration. Thatorchia: torture and death of and by the testicles. Spiritual orchiectomy. The long-attested proximity of sex and death. Étienne = Stephen = the first martyr. (On Tumblr she says it’s some French architect, but let’s go with my interpretation instead; trust the tale, not the teller.) “I will claw my way back to the Great Dark and we will not speak of this place again.” Thus the pervert’s only possible redemption is to return to the light/dark origin outside this imprisoning cosmos from whence he and we fell, if he/we can, extinction only in and only through the victimless orgasm:

Only God knows, only God would believe

That I was an angel, but they made me leave

They made me leave

I respect the aesthetic integrity of the project—what she has, also on Tumblr, defined as an “erotic project.” Poetically, a hymn to the autoerotic reminiscent of a darker Whitman, of a Poe/Whitman collab. Musically, I’m not sure it’s for me. One may learn something about eros in general by observing somebody else’s fetish (“I have always possessed the insatiable need to see what happens inside the room”), but it doesn’t exactly guarantee one’s own pleasure.

After those interpretive labors, I am still not moved to become more of a supra-critic than I already am, much less a music critic. You know what they say: writing about music is like masturbating about architecture. Some do it well, but most can’t do it at all.

It’s a bit of a commonplace now that the discourse is better, or at least more in line with the zeitgeist, on here than in the legacy publications. As the zeitgeist turns increasingly from secular solutions to the mounting challenges of our vertiginous post-post-post-modernity, I note here only two examples from this week of relevant discourse by friends of the blog. First, there’s an essay Mary Jane Eyre, helpfully linking to a number of other recent posts about gnosticism (some from friends of this blog as well as MJE’s and some new to me) and putting them into conversation with Quakerism. (Full disclosure: I’m also down in the comments with a colloquy on Quakerism, Virginia Woolf, and Iris Murdoch.) Then there’s Mars Review of Books editor Noah Kumin with a tantalizing piece on Robert Graves and the perennial religion, which doubles as a taste of his (Noah’s, I mean, not the grave-bound Graves’s) nonfiction book-in-progress, The Mystagogues, a study of five 20th-century writers and their own relation to the secret religion behind all religions. Of his promised quintet, Noah, now spearheading a Graves revival, has already promoted Roberto Calasso and has also introduced me (see here) to Colin Wilson; I look forward to making the acquaintance of Ioan Culianu; Vladimir Nabokov needs no introduction, but just in case he does, I might mention that we’re doing an episode on Pale Fire this year in The Invisible College.

Flames, Hollywood: what to say? One shies from the presumptuous well-wishes of the parasocialite (“I hope my fans in L.A. are doing all right!”), as if evacuees were urgently checking Substack to see if one had offered one’s prayers, or as if one were signing up to comment on every bad thing that ever happens and not just those to which one selfishly feels some personal connection, however tenuous. And yet I do hope you’re doing all right. The “discourse” has been unusually bad, with the (l)it-girls quoting Joan Didion, the theory-boys quoting Mike Davis, and the better-read-than-thou reminding them that Nathanael West is more germane than either. Is this the best use of one’s time in a public emergency? I have been wondering about this since people circulated Auden online (“The unmentionable odour of death / Offends the September night”) after 9/11, perhaps the first instance of the internet’s rush to match the literary work to the unfolding spectacle of disaster. Irretrievable cultural loss, sourced from social media: the library of Gary Indiana, the papers of Schoenberg, the largest Theosophical archive in the world. Though from Ryan Ruby, Thomas Mann’s enemy, one learns the house where Mann wrote Doctor Faustus has been devilishly spared. Tenuous personal connections: I only spent five weeks in L.A.—in strange circumstances detailed here—and came away with two short stories, one chapter of Portraits and Ashes, and seven chapters of Major Arcana. Something about the city, its ineffable mix of dread and beauty, of glamor and terror, cannot fail to impress the literary imagination, presumptuous (again!) as it may be to say in the moment; the best of those short stories ends, like The Day of the Locust, with a premonition of doom. And I can match the literary work with the disaster, because I’ve been commissioned to write something about the L.A. novelist Bruce Wagner, a Dickensian-Joycean laureate for whom the city has been a flâneur’s home since childhood and not a visitor’s dreamscape, and I’ve been reading his books one after the other for the last two months, all of them studded and jeweled with the place-names we’ve become familiar with whether we’ve been to the places or not. I hope Bruce is doing all right, too. A visitor’s perspective from his Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, a passage eventually ironized by the brutal narrative context—you’re always a page away from obscene and apocalyptic calamity in Wagner—but a genuine (I think) sentiment:

He stopped at Erewhon in the Palisades to buy sushi. It felt good to roam. He was like a blessed pilgrim, a spy in the city of God—a city suffused with [her] energy, laugh, smells. He drove down a long residential street that deadended at a bluff. He parked and took a stroll in the soft sun and bright wind. I could get used to this town. The houses looked older, stately, sedate, as if still having their original owners; you could almost see the ghosts of 40s movie stars rambling inside. He stood at a low wooden fence and stared at the magnificent ocean’s red tide. How strange and wondrous this world, how lucky he was!

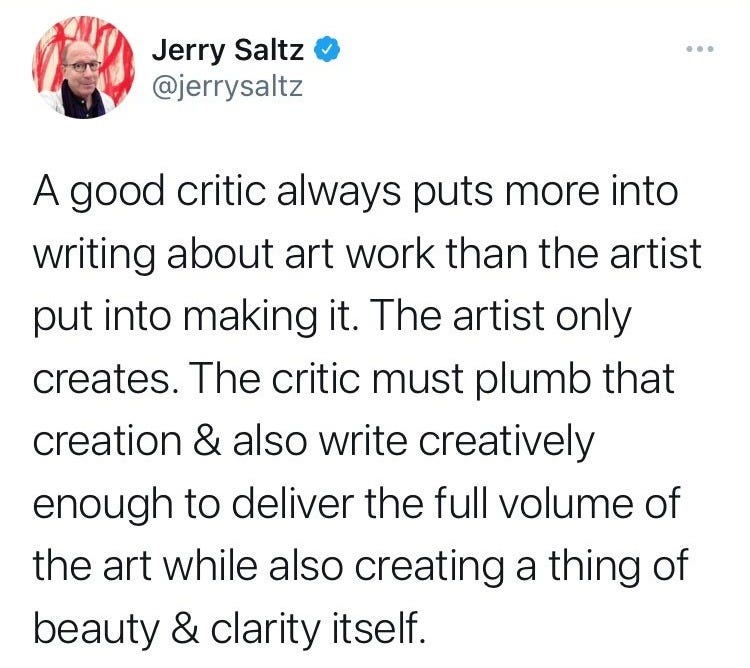

This reminded me of something I wrote years ago on Tumblr, which might be worth resurfacing here. I was responding to a then-viral and then-controversial then-Tweet by the art critic Jerry Saltz elevating criticism over art. (Critical discourse that spans the arts often seeks to put the arts into a hierarchy. Note that the painting I used to decorate this post elevates painting itself over its sister arts: the central figure of painting eclipses architecture and music entirely and is adored by sculpture as she actualizes poetry.) I repost the Tweet and my annotation:

Saltz is a critic of contemporary fine art, a tradition that is heir to Duchamp’s aforementioned relocation of aesthetic interest from eye to mind. This fulfills Hegel’s contention, in his Lectures on Aesthetics, that philosophy will take over from art in the progressive actualization of human consciousness. The post-Duchamp fine artist need only make a gesture, sometimes not a very laborious one—the famous pile of dirt on the floor that the museum cleaning staff almost sweeps up—while the critic tasked with interpreting it must apply a Hegelian intensity of intellect. In that context, Saltz’s controversial Tweet is not only correct but obvious. (In a follow-up Tweet, Saltz usefully recommends Wilde’s “Critic as Artist,” a maximally funny, lyrical, seductive statement of the Hegelian position—much more fun than Hegel!) Given other forms of art, even other forms of visual art, though, it might be absurd. Though even here, we might ask, “puts more” of what? In my own experience, fiction is infinitely harder to write than criticism—I can’t understand these Trollopeses and Oateses, who seem to be serious novelists but just crank them out like an assembly line. The difficulty involved is not an intellectual one, though it’s not exactly an emotional one either. When I’m having trouble writing a novel, the problem is never with writing sentences or even coming up with characters and events, but with what goes where, which is not wholly a logical or syllogistic problem, though it may be that as well, but one of vision and sensibility. This doesn’t go there, and I need something else here, but I don’t know what it is yet—these are the thoughts and feelings that torment the fiction writer and probably every other form of artist, until the real structure comes into view, as when Lily Briscoe completes her canvas by intuitively painting an abstract line down the middle, analogous to the asubjective corridor of time that bisects To the Lighthouse itself. (Dealing in abstraction, Woolf gives us the form of the artist’s problem, which also applies to art that is not abstract.) I don’t doubt that the critic puts more intellect into the extrusion of truth from the artwork. But precisely because we can’t give a name to what the artist puts into the artwork’s organization of truth, or at least a better name than the rather mystical and self-congratulating “vision,” we know it exceeds intellect per se—and we see, too, the limit of Hegel’s claim.

I gotta read those Bruce Wagner books, that's a great passage. Which one do you recommend?

I had to evacuate but it looks like my apartment is going to be okay, though I can't say the same about everything a mile or so north of me. It certainly gives a new perspective on all these things that are discourse topics of the day, to suddenly be in the middle of one.

The footnote of imagined reviews is too good. Here’s hoping some of them actually review it so we can compare