A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Chance and coincidence sent me to Brecht, again or for the first time. “Brecht” seems to be the name of an artistic concept, so that once you’ve learned about the concept you don’t entirely feel you need to read or see the artist’s own exempla. But when Godard died—Godard, the Brecht of the cinema—I briefly thought I should pay more attention to the German dramatist. And then, on a Sunday walk through a downtown neighborhood that was once a warehouse district and is now a haven for the youthful upper ranks of the professional middle classes, I found, in a Little Free Library gray as a sniper tower in East Berlin, an ancient paperback of Parables for the Theater. It was right next to a crumbling old Moll Flanders Penguin paperback, of all things—as if these had been the first and last readings in some mid-20th-century senior seminar on “The Literature of Capitalism.” I try always to take hints from the universe, so I read Brecht, for the first or last time, and in search of higher understanding I even sought the aid of Benjamin and Adorno. I rendered a mixed verdict, in the end, as Adorno did:

Culture “seeks to do away with classes,” as the man said—and so as an artist I venture to speak or at least to stammer for humanity tout court. But as a reader of Brecht I resume my judgment that Marxism’s world-historical destiny is to operate as capitalism’s loyal opposition and junior partner. Its commission: to exterminate the petite bourgeoisie (e.g., “abolish your kitchen”), with the blood-libel justification that they, or we, and not the upper bourgeoisie, are to blame for fascism. Otherwise, the lower middle class’s ribald independence, hymned as it’s been from Chaucer to Dickens to Joyce, might otherwise prevent the pulverization into calculus of every last thing on this earth. (Mother Courage, though—that one almost brought a tear to my eye. Kattrin!) For a free artistic exploration of the class of my birth, I direct you to the excerpt from my 2021 novel The Class of 2000, posted this week as part of our new Wednesday creative writing feature.

Elsewhere online, if you liked my rumination on Wallace Stevens last week, you owe it to yourself to listen to Jacob Siegel and Phil Klay discuss Stevens and Gerard Manley Hopkins (the great unbeliever, the great believer) on the latest episode of Manifesto! A Podcast.

Below I offer two little essays for your Sunday reading: the first contains further thoughts on A.I. art (and a confession about my own use of it) with reference to Jed Perl’s recent book, Authority and Freedom: A Defense of the Arts; and the second is a contrarian riposte to that hatchet job on Ian McEwan in the New Left Review everyone loved so much on Twitter.

Total Machine: Half Against A.I. Art

Katherine Dee has argued in several places that the left vs. right and woke vs. anti-woke culture wars will soon be succeeded by a related but not identical fight over the role of technology in our culture. No recent book proves this thesis more, however inadvertently, than art critic Jed Perl’s elegant little 2021 manifesto, Authority and Freedom: A Defense of the Arts.

Exemplifying a cultured disinterest in political quarrels, Perl rarely takes direct aim at the forces he wants to defend the arts from. He confines himself in his first and last chapters to general statements like the following, and leaves his concluding discussion of the red rejection of modernism in the 1930s to do the rest of his argumentative work by implication:

I want us to release art from the stranglehold of relevance—from the insistence that works of art, whether classic or contemporary, are validated (or invalidated) by the extent to which they line up with (or fail to line up with) our current social and political concerns.

Yet the rest of the book has little to do with challenging political critics at all. This almost seems like a tacked-on marketer’s justification. The book is really a series of quiet and lovely capsule studies showing how artists earn their creative freedom through an absorption in the authoritative structures and traditions of their chosen forms. For Perl, this apolitical conflict between form and tradition, on the one hand, and individual agency, on the other, is the essence of the artistic process, to which questions of sociopolitical relevance are at best secondary.

Perl heartens and entertains with his wide-ranging exemplary cases: Verdi’s instructions to his librettist to match the verse to the music, Michelangelo’s experimental and delirious architecture, Aretha Franklin’s transformation of gospel song into secular anthem, Anni Albers’s textile art patiently learned from Peruvian weavers, Picasso’s conversion of personal myth into public outcry in Guernica, Auden’s elegy for Yeats in all its public-private ambivalence, Katherine Anne Porter’s praise of Virginia Woolf as consummate artist: “She lived in the naturalness of her vocation.”

No, Perl barely cares enough about the woke to refute them; like Woolf, his true homeland is the arts. But I felt a nagging sense of urgency and relevance as I read through the slim book even so. This book is about something important that’s happening right now, just not radical politics. What could it be? Then I understood. Authority and Freedom tells how a human being—the artist—attains freedom by patiently struggling with and against the transpersonal and inhuman elements of art: the laws of form, the concreteness of material, and the carapace of tradition. It’s about the irreducible human element in art, and so it is also, without Perl’s being even slightly aware of it, the first great polemic not against the politicizing of art but against its mechanizing—against, that is, A.I. art.

Speaking of polemics against A.I. art, Walter Kirn wrote a usefully pugnacious one just this weekend, for Bari Weiss’s Common Sense, an argument in Perl’s spirit:

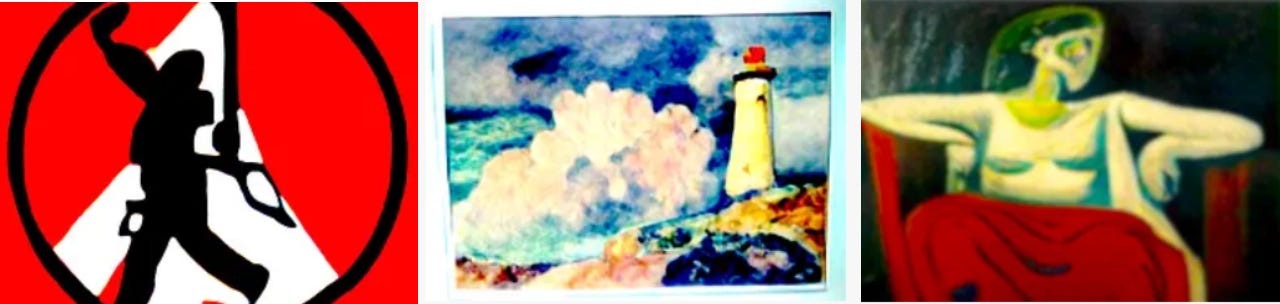

Which would be a good time for me to confess something: I created the header images for the last three “Weekly Readings” posts using the DALL-E mini. (Not this week’s, though; that’s a photo I took of some graffiti in the neighborhood.) Here they are lined up in order:

The second and third aren’t so good. I asked for pictures of “to the lighthouse” and “antigone,” selected my favorites among the presented options, and tweaked the coloring a little; but all I got was second-rate Impressionism and second-rate Picasso, the kind of thing you’d find in a waiting room. Despite my own role in the process, it never quite amounted to great art, which may or may not be my fault. As Perl might say and as Kirn does say, the robot can only regurgitate what humans have already made. It lacks the shaping force of true artistic agency, what Blake describes here:

If it were not for the Poetic or Prophetic Character the Philosophic & Experimental would soon be at the ratio of all things, and stand still, unable to do other than repeat the same dull round over again.

Yet I confess to a fondness for the first A.I. image I created. I requested a picture of “anti fascism” and did little more than bring up the colors. Like the best A.I. art, it’s nightmare fodder: almost but not quite a legible sigil, properly scarlet and black like every extremist standard, the flag of a regime just glimpsed as it marches by in a dystopian dream. Dreams, too, only recombine the detritus of day, though I never scant them as sources of sign and portent. The portent here—A.I. art is most convincing when asked to generate a totalitarian banner—suggests that defending art against politics and defending it against mechanics might be the same fight in the end.

Critical Capital: Half Against Marxist Criticism

[This is an expanded version of some polemical jottings originally posted to Tumblr.]

On social media this week, everybody was in ecstasies over Ryan Ruby’s “The Pundit”, an artistic and political demolition job on the new Ian McEwan novel, so I thought I might offer a corrective objection or two. Please bear in mind that I have not read this novel, and that I do not in general admire the novels of Ian McEwan—I’ve read four and a half—even slightly. I hate to mention this document again, but my doctoral dissertation literally opens with a left-wing critique of McEwan, in this case his post-9/11 day-in-the-life novel Saturday. I’d phrase my academic criticism differently if I wrote it today, but the main point—that McEwan cynically stacks the narrative deck in favor of Bush’s and Blair’s war and of technocratic imperialism at large—still stands. Yet Ruby’s censure of McEwan has more in common with technocratic imperialism than we might think at first.

Doesn’t the review’s most popular passage, Ruby’s rhetorical catalogue of prose missteps in the novel, for all that its “zinger” quality seems unanswerable, overvalue expert correctness at the expense of the intangibles on which novels have always thrived even when composed by the linguistically inartful?

Everything in Lessons, whose story concludes within a year and a half of its publication date, gives the impression of having been written in extreme haste. Its prose, for example, is pocked with first-order clichés (‘trying to escape his own demons’), second-order clichés (‘a demon he hoped to slay’), dull metaphors (‘Time, which had been an unbounded sphere in which he moved freely in all directions, became overnight a narrow one-way track down which he travelled’), mixed metaphors (‘ten on the pain spectrum’), limp similes (‘Some love affairs comfortably and sweetly rot. Slowly, like fruit in a fridge’), oxymorons (‘a settled, expansive mood’), pleonasms (‘the photograph which would posthumously survive her’), catachresis (‘domestic violence – generally code for men hitting women and children’), jejune diction (‘the creepy shifting shadows’, ‘the magical or silly element’, ‘shivery’, ‘mushy’), trivializing double entendres (‘Lucky too that so far no child was left behind’), pomposities (‘They rose in his thoughts as a black hammerhead cloud of international disorder’), flagrant abuse of self-reflexive questions (‘Would Roland have had her courage?’, ‘What held him back?…Courage. An old-fashioned concept. Did he have it?’, ‘In the face of it would he, Roland, have risen to Sophie and Hans’s courage?’) and barely-concealed cribbings from more talented stylists like Nabokov (‘parenting, its double helix of love and labour’, ‘seven paces up her short garden path, his signature taps at the door – crotchet, triplet, crochet, crochet’).

No doubt this kind of exercise can be fun—I’ve probably done it myself—lifting this solecism and that infelicity out of a 500-page novel. But it mistakes what novels are for and how they work. In lyric poems, language reacts upon itself. None but the lords of language—e.g., the aforementioned Hopkins and Stevens—need apply. In novels, though, language supersedes itself; novels must go beyond language if they are to live at all. Even in the case of someone like Joyce: all those verbal miracles would have been for nothing if they hadn’t built up the Blooms. And the verbal miracles prove in the end less necessary to novelistic creation at its best than a solid, burning, spinning core of ideation.

Such fussiness as picking one maybe-catachresis out of a long book is what led Nabokov, that commander of the second rank, to think he was a better novelist than Dostoevsky just because he wrote finer prose. Nabokov carved very beautiful little figurines in jade and lapis lazuli, but Dostoevsky built cathedrals into the sky out of splintering rough-chopped logs.

At the essay’s conclusion, Ruby weds his aesthetics to his politics when he argues that novelists should merit the “privilege” (sic) of their freedom by writing works rigorous and experimental enough to have hypothetically earned the author’s martyrdom at the hands of some Soviet-style state or perhaps a freelance assassin suborned by the rulers of Iran:

On the other hand, we need look no farther than the recent assassination attempt on McEwan’s friend Salman Rushdie – the 1989 fatwa against The Satanic Verses is among the events catalogued in Lessons – to concede that freedom of expression is not as secure as we would like it to be. And we may grant that, as a novelist, McEwan has a legitimate interest in its preservation. But it is precisely qua-novelist that he has a special responsibility to freedom of expression that goes above and beyond that of the pundits who argue in its defence in op-eds or even that of advocacy groups like PEN that raise money and awareness on behalf of writers around the globe who have seen their work banned or who have been imprisoned, attacked, harassed or murdered for publishing it. It is this: to create a work of literature whose aesthetic power justifies the privilege in the first place. Without such power, all we have is yet another commodity – far too disposable a peg on which to hang the values of an entire civilisation. Just as people living behind the Iron Curtain had no shortage of reading material as mediocre as Lessons, the market is currently condemning far better books than it to smaller print runs than a samizdat. A bestselling, Booker Prize-winning Commander of the British Empire, McEwan is not obscure, nor is he powerless, according to the Daily Telegraph. Lessons was written in perfect freedom. What did he need it for?

I wonder what other civil liberties we should come to deserve through expert-vetted good behavior? Whereas, John Stuart Mill contended, free speech necessarily includes the right to be wrong, since no one can possibly know all that’s right in advance of experience.

But in Ruby’s drama of freedom earned through aesthetic worth, of freedom as contingent privilege rather than absolute right, who could possibly know if the artist had succeeded but the critic? The critic’s freedom—indeed, the critic’s privilege—is assumed, is never put into question. With a sleight of hand, the critic’s authority is even placed on the same level as the state’s right to apportion justice, a right to which, Ruby distinctly implies, civil liberties will necessarily be subordinate. And we might remember that Ruby recently charged W. G. Sebald, too, of failing properly to challenge neoliberalism—Sebald, a writer who couldn’t resemble McEwan less. Some aphorism about hammers and nails—not hammers and sickles—comes to mind, as do recent pieces by Anastasia Berg and Clare Coffey on the dubious relevance of dragging capitalism into every question until “capitalism” itself becomes little more than a synonym for what an older tradition would have just called original sin or the fallenness of the world.

If I told you to read The Rebel for an extended commentary on this line of thinking, and one perfectly aware of what’s wrong with capitalism too, Ruby might accuse me of irrelevantly dredging up antediluvian anti-communist rhetoric, so take it instead, please, from a source less easily dismissed with such shibboleths:

We went on to discuss Russian literary policy. I said, referring to Lukács, Gábot and Kurella: “You can’t put on an act with people like this.” Brecht: “You might put on an act but certainly not a whole play. They are, to put it bluntly, enemies of production. Production makes them uncomfortable. You never know where you are with production; production is the unforseeable. You never know what’s going to come out. And they themselves don’t want to produce. They want to play the apparatchik and exercise control over other people. Every one of their criticisms contains a threat.”

—Walter Benjamin, “Conversations with Brecht” (1934)

This response to Ryan Ruby's review of McEwan (who holds less than no interest for me) is -- to employ a criterion it explicitly disclaims, as least for fiction -- pitch-perfect. Bravo.