A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week, as pictured above, I acquired galleys of Major Arcana, my new and forthcoming novel, which will be released in April 0f 2025 by Belt Publishing. You can pre-order this beautiful object here. The distinguished novelist and screenwriter Bruce Wagner was speaking of the text, not the book, when he wrote that “to read it is to hold the heart of the world in one’s hands,” but why not hold a fine volume as well? (Major Arcana will also be released in a Kindle edition as well if you’d rather hold a device. And if you can’t wait until next spring to hold it in any form, paid subscribers to this Substack can also access the original serial of the novel, complete with my audio rendition.) A new five-star review of Major Arcana was also published this week to Goodreads. I gratefully quote from it here:

I don’t have any connection with the author, a friend of mine just talked it up so much that I picked it up, and I was really glad!

The book is compulsively readable. It starts with a shocking event and then traces back many threads of how that event came to be. I think it's a testament to the quality of the writing overall that, although I didn’t ultimately find the full explanation that convincing, it didn’t bother me that much. There are many great characters in the book and, as I often find with self-published books, it was very hard for me to predict what was going to happen, which makes it more exciting. (I was definitely surprised with, if not the details of the ending, the tone.) A lot of implicit and explicit discussion about the value of art and ideas, and the struggle to lead an authentic life.

While there are things that I think could have been done better, I can’t think of a book I’ve read this year that I want to discuss with other people more!

Speaking of flawed and great—of greatly flawed—American novels that provoke discussion, I posted this week “In Nomine Diaboli,” the third in a three-episode sequence on Moby-Dick for The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. If you’d like to discover the infernal secrets of this most revolutionary of American writer’s most celebrated and most “wicked” of books, please offer a paid subscription. Thanks to my current paid subscribers! For my future paid subscribers, you have a burgeoning archive of discourse awaiting you: 19 weeks on British literature from Blake to Beckett, eight weeks on James Joyce (with a focus on Ulysses), and four weeks on Eliot’s Middlemarch, as well as our ongoing American literature survey, which continues in the next two weeks with episodes on those greatest of American poets, Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson.

For this week, I post with additions and footnotes the best of my recent Tumblr Q&As. Please enjoy!

Queuein’ A: On Sentimentality, Juvenescene, Media, Comics, Genius, and Underrated Books

Someone wondered if I regretted publicizing on Substack my “super-secret Tumblr” where anons ask me questions, but I don’t even link to it! People find it anyway, which is fine. Some anons are asking more and more intrusively personal questions; I never answer those.1 To them I say this: if you want to know about my economic and erotic situation, what I once referred to as the “Marx” and the “Freud” of a person’s life, the best thing you can do is make me famous so you can read the details in the unauthorized biography. In the meantime, I must, like the aforementioned Chappell Roan, retain my privacy and my dignity.

Anyway, I answered a lot of questions this week and consequently have not an original literary thought left in my head for this Sunday post.2 For those who don’t know about my super-secret Tumblr, then, and so these thoughts don’t disappear into the void of a defunct website like tears in the rain, I offer a digest of some recent Q&As that might interest my increasing company of Substack readers.3 I will format it as if it were an interview conducted by a scatter-brained inquirer.

Question: What do you think is the proper role of sentiment in a novel? Have you ever read a book you deemed to be of high literary merit that also made you tear up?

Answer: I wouldn’t be inclined to make rules about such things. In the culture of serious literature that developed after the modernists discredited sentimentalism, overt emotional appeals tend to be less effective—to me, anyway—but this is probably changing for what’s left of the literati with the YA-ification and anime-ification of everything. Presuming for a moment the modernist standard, however, Dickens’s overt rhetorical appeal to our tears—or that of other 18th- and 19th-century novelists—is just too forceful not to feel almost funny or grotesque. Dickens’s most moving scenes for me, the ones that inspire tears, are not the author’s theatrical exhortations to the reader upon the death of a symbolically suffering character like Blackpool in Hard Times or Jo in Bleak House but rather the more understated moments, like Joe writing “wot larx” in Great Expectations or the drowned Steerforth seeming to rest his head on his arm as he’d done in life in David Copperfield. So in answer to your last question, yes, of course, many times; I almost think it would strange not to, in the presence of Lear’s outraged suffering or Bloom’s fragile dignity or Ivan and Alyosha’s quarrel about God, etc. Usually not, however, when the author’s appeal to sentiment is most obtrusive and therefore obviously manipulative. But this goes for every other reaction too, from laughter to awe to fear.

Question: Do you feel somber at so many people retreating into juvenile-at-best “media,” or do you see it no different than when a pig eats its plow—just the nature of things for which no muscle should grimace as if it heard a grimace shake joke after the astroturfed marketing long has dried up?

Answer: The poet Les Murray said there are only two centuries: the 19th and the 20th. I assume he meant that those are the only two centuries when the dream of progress—specifically of lifting up the masses to heights of culture and cultivation previously only occupied by the cream of the aristocracy—was so real to people that it seemed reasonable to demarcate time in such narrow slices as decades and centuries, rather than (e.g.) centuries-spanning dynasties. Progress so conceived seems to be an outdated concept that no longer commands any allegiance. (Politically, the right never really believed in it, while the left appears to have given it up in favor of managed decline, the humane regulation of a peasantry by a brahmin class.) We are reverting back to a world of stratified tastes and warring houses, of coteries and courts; the very agents who used to be tasked with uplifting the masses now claim that their pedagogical abdication is progress itself, emitting excuses they seem not to recognize as essentially eugenic. In these circumstances, it seems pointless to lament. As I have already said somewhere, by the standards of what used to be considered erudition, my not knowing Latin and Greek—and my remaining too lazy to learn them—means that I with my plebeian blood might as well masturbate all day to video games as read modern literatures in vernacular languages, almost exclusively my own in fact. So no, I can’t summon much judgment against other people’s tastes.

Question: bruh you were way too soft on Katherine Dee’s last piece man u and Sam both like bruh I thought u we’re all highbrow (Okay but really, how badly do you regret mentioning your Tumblr on Substack?)

Answer: I’ve never—or, if not “never,” then I haven’t recently—positioned myself as defending the highbrow or high culture per se.4 KD’s last words when she appeared on my pod over two years ago were, “Read Joyce.” (Directed against Angelicism01, as I recall, and where is Angelicism01 now?) The mentality that went into the writing of Ulysses—a detached fascination with new media—is closer to the attitude that informs her work than is a defense of high culture on largely social or political grounds. I’m more optimistic than she is—or maybe I care more than she does—about the survival of longstanding artistic forms, but those old forms will only survive if they incorporate what is vital in the new forms. The Eliot who wrote The Waste Land with jazz rhythms and cinematic montages and music-hall raucousness in mind would absolutely be scrolling TikTok right now, or whatever comes after TikTok, as would the Woolf who put the skywriting plane at the beginning of Mrs. Dalloway. To say nothing of Pynchon or DeLillo! Remember, the watchword around here is “juvenescence.”

(Also, I don’t know what some people have against Katherine—that she’s a journalist, not a philosopher? that she’s a centrist, not a radical or reactionary?—but I’ve always found her work illuminating, sensitive, thoughtful, and prescient. Her recent essay, “Adam Lanza Fan Art,” marks a new height of maturity and gravity in her work.)

Question: Do you wish there were more comics with the same “literary value” as the greatest and most sophisticated books? Or would the talent be wasted on these silly little picture books?

Answer: I have reluctantly concluded that comics belongs more to the visual arts than to literature. The attempt on the part of ambitious writers to make it a high literary form eventually failed, leading those writers to leave comics for novels, and for the “literary” graphic novel itself to dwindle into YA propaganda, a mere prop in the “banned book” wars.

(Elif Batuman ingeniously grasped the relevant cultural logic years ago: the secret interrelation of American comics’s two most characteristic genres, the superhero saga and the misery memoir, how they suture individual time to historical time, and therefore inevitably serve together the ends of progressive propagandists for the right side of history, as indicated by her application of Lukács’s theory of the historical novel. And then she never wrote about comics again—except, in anticipation of the discussion of “black holes” at the end of this post, to extol the filth of Pigpen.)

I am now more interested in comics, to whatever extent I am still interested in comics, that explore the medium’s potential as a visual form than those that try to recapitulate the effects of the novel in the absence of the novel’s verbal density.

(Note, for example, how often Alan Moore, the best comic-book writer qua writer, “cheats” by turning his comics into pure prose, in the literal prose passages of Watchmen or Providence, or in the long and intricate narrative captions of Swamp Thing or soliloquies of From Hell. Only in the latter work, and perhaps in the also prosy Lost Girls, did he collaborate with an artist as concerned to make an innovative statement in the history of visual art as Moore was to take his place in literary history.)

In more direct answer to your question, then, I wouldn’t demote comics below “real art” or whatever, but trying to make them into literature increasingly seems to me misguided. As I wrote in my review of the Norton Critical Edition of A Contract with God, considered by some the inaugural graphic novel, and the first graphic novel to take its place in Norton’s canon,

Critics like Gary Groth, founder of The Comics Journal and hanging-judge of comics criticism, whose 1988 dissent on Eisner’s stellar reputation in the field the Norton volume reprints, complain of Eisner’s simplicity and melodrama. They aren’t wrong, but this too strictly mis-applies literary standards and undervalues the integrity and authority of his images. It’s true that Eisner makes no philosophical innovation with his parabolic crossing of the The Book of Job with Silas Marner; the story just re-states the ancient problem of theodicy. But the power is in the statement itself. If A Contract with God can’t compare to the intellectual sophistication of a Saul Bellow, Eisner’s dense line work and dynamic compositions, his use of image as text and text as image, offer a visual correlate to Bellow’s verbal richness. It’s only aesthetically illegitimate if you don’t take the visual seriously enough.

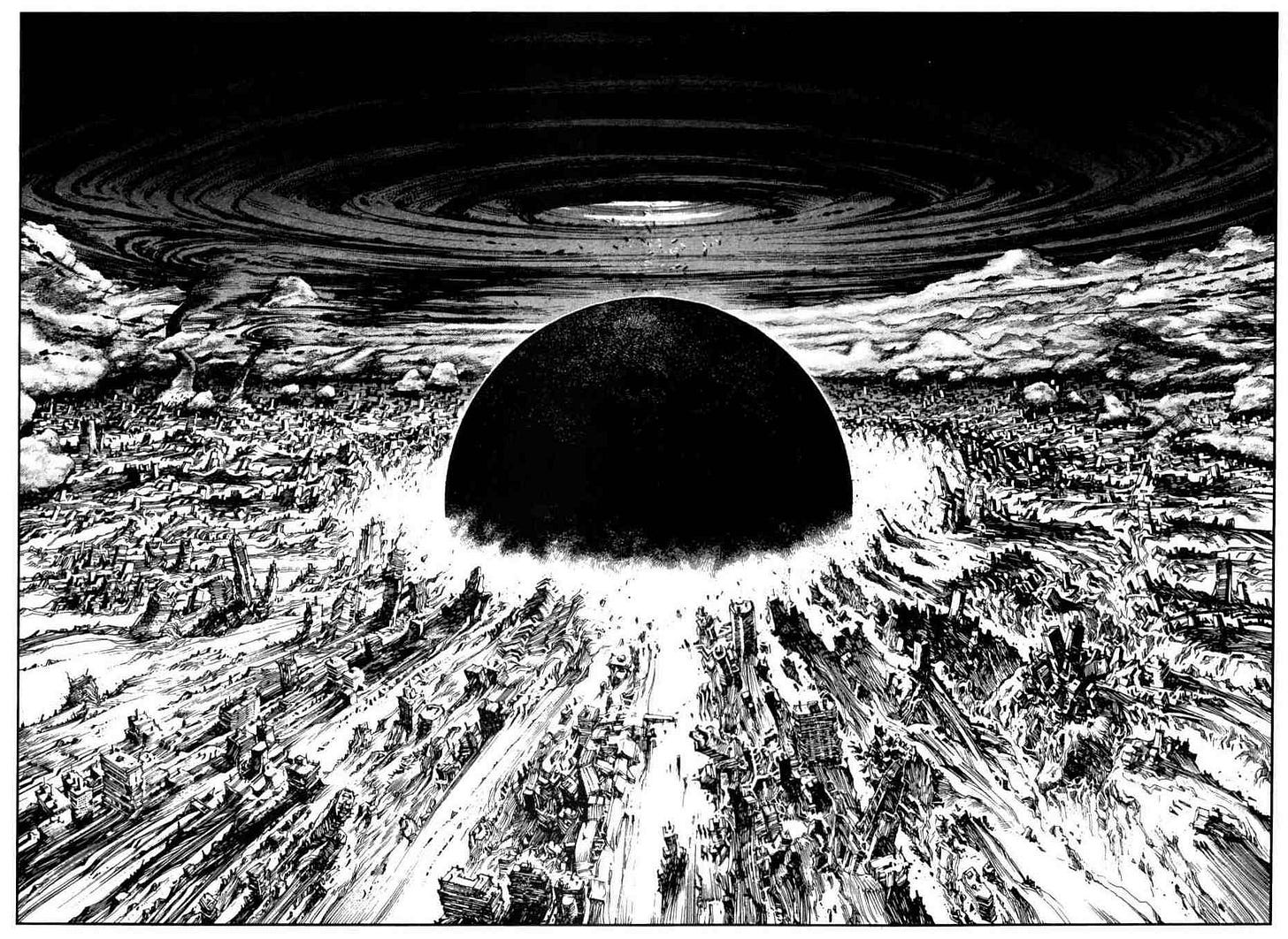

My review of the semi-illiterate visual extravaganza Akira also pertains here:

So mighty is Otomo’s storytelling craft that it paradoxically consumes attention even as it commands it, which neither Miller nor Moore, neither Jodorowsky nor Peeters, would be willing to do. In other words, you are never tempted to linger, but only to speed on. It is only a very slight exaggeration to say that one of Akira‘s six 400-page chapters can be read in the same time that it takes to read one of the 32-page chapters of Watchmen: about an hour. This reflects Otomo’s absolute mastery of layout and composition; he never puts an obstacle athwart the onrush of your eye across his collapsing cityscapes. Language does not get much in the way either: vast swaths of pages, all violent action, go by with no more demanding words than onomatopoeiac sound effects, grunts and profanities from the characters, and the heroes and villains crying one another’s names. […] Such anti-literacy—very much against the Anglo-American “spirit of 1986,” which saw comics strive for and often attain the density of the 20th-century novel—bears upon Akira’s theme of energy washing away all hierarchies.

(These remarks are partly inspired by the recent Weird Studies podcast episode on Charles Burns’s Black Hole; there the hosts construe comics as a hybrid form of archeo-print-culture, a printing of the manuscript, and an unfolding of the spiritual-material potentialities of ink, Burns’s book’s secret eponym. Otomo’s lovingly rendered Neo-Tokyo apocalypse is another such “black hole” from which the image stream proceeds, of course, as is Eisner’s famous rain of ink out of the whirlwind sky upon his Job-like characters.)

Question: Have you ever read a book that was virtually unknown even in literary circles, yet great?

Answer: I notice that great-but-unknown books are getting memed more and more into popularity or at least cult status by social media. There’s Mating, of course, which I find unreadable. But when did I Who Have Never Known Men become the it-girl/hot-girl book of the decade? Or Come Closer everybody’s hip Halloween read? As one heard the band in a small club before it started selling out arenas, I read these two now-trendy novels years before BookTok did, for whatever it may be worth. I remember enjoying the latter, but not the former.

I unimaginatively read too many already famous and canonical books for this exercise, but I will put it in a word—though it may have missed its moment now that we’re so post-woke—for The Fortunate Fall, a 1996 cyberpunk hallucination, a lesbian love story by a trans writer who never wrote another novel, a political thriller about genocide and environmentalism and online news and internet swarms and Slavo-dystopianism and Afro-futurism and brain implants, a prose-poem spiked with Shakespeare, Milton, Melville, Stein, and Nabokov, and an all-around under-rated book. I read it when I was 14 in 1996, plucked from the new book shelf at the public library, and never forgot it. In some ways, it is only intelligible now. I see it was republished literally two months ago, so here is everybody’s chance to turn it into the new accessory.

(Also science fiction, also gathered at random from the new shelf at the public library, also prose-poetic and cyberpunk-adjacent, also unknown, but much more recent, is The City of Folding Faces, which I wrote about here.)

Question: Have you ever entertained the notion that you’re a genius? Did you find that sort of self mythology empowering or crippling for your art?

Answer: Only in the form of a joke. You can’t take yourself too seriously! Also, if you make things, you need to worry more about what you make than about who you are. Many a soi-disant genius was immobilized by self-mythology into not making anything at all. (This trap can take many forms from Romanticism’s excessive focus on the artist as a special type of person—the more balanced Romantic idea is that the artist lives out a heightened, representative version of every person’s creative capacity—to the identity politics of today where artists are supposedly their race or gender incarnate.) I do enjoy that Namwali Serpell quote I once posted on here comparing Vladimir Nabokov and Toni Morrison for their seemingly indomitable, aristocratic confidence. I’m like that too, about my work anyway. If it were only Nabokov, we could attribute it to a privileged upbringing—his was more privileged than mine, mine more privileged than Morrison’s—but such self-assurance probably results less from broad social conditions than from more narrow familial and/or educational ones. I suspect the three of us were just praised a lot as children. That can lead to unearned arrogance—again, the self-styled artist who makes no art—the bad outcome that parents and teachers who are chary with praise reasonably fear; but it can also lead to the self-assurance necessary to create things. I don’t know how it explains the taste we three—Volodya, Chloe, and I—share for melodrama, however, a taste generally counted against the novelist, however ironized it may be, by those who appoint themselves the critical arbiters of genius.

And sometimes even about other people’s lives, which I usually couldn’t tell you about even if I were willing to, and I’m not. I might just suggest, however, from one conspiracy theorist to another, that it’s pretty unlikely for a niche culture reporter to be operating on secret business under the covert auspices of the federal government. And I say this as someone who would do it for the right price—the right price, in this case, being on the low side. In other words, they’re not offering. See my essay on The Scarlet Letter, please: American culture converts extremes of dissent into the utopia of endless argument, just like our old Italian pap-pap tried to tell us this month in Megalopolis, and considerably at his own expense. No feds needed! I know perfectly well what the CIA did in the midcentury—I’ve written about it here and here—but there are good reasons other than intelligence agency interference for people, especially professionals who rely on a culture of free speech, not to be communists or fascists. Speaking of Megalopolis, friend-of-the-blog Ross Barkan contributed a tentative endorsement this week in Compact. Anna and Dasha, meanwhile, didn’t get my memo that the film reflects their own politics, since they denounced it this week, albeit somewhat affectionately, as the dementia-addled ramblings of a Boomer lib. I find it touching that they don’t recognize their own version of MAGA politics for what it is: a Millennial nostalgia for the bygone consensus at the verge of history, a longing for the mythical return of the True Reagan. (Whereas, as implied in my own Megalopolis essay, I understand this perfectly and ruefully well about my own political unconscious; Reagan is my birthday twin under whose aegis and in the second year of whose administration I was born, my fellow Aquarius-sun world-making visionary, after all.) We will all be Boomers in the end; Boomers, and then bones. On that note, to judge from their Halloween-and-election yard décor, the gentry liberals of a tony urban neighborhood I strolled through in Western Pennsylvania this week seem to be unconsciously grappling with what may (only “may”) be about to happen; either that or they have resorted to an esoteric statement of political commitments they feel unable to express openly.

Symptomatically, the literary discussion this week—which should be the biggest week of the year in the world of literature, when the Nobel is announced—seemed muted, even though the Prize went to a well-known writer. My contribution was and must remain nothing more than link to my review of her most famous book, which, to be candid, I didn’t quite care for.

I do like it when—and this happens with amusing frequency—someone subscribes and then unsubscribes five minutes later. I gather the “incendiary footnotes” are to blame. As Substack becomes more and more the home of the mainstream literati, it grows to conform more and more to their politics. But its original center of political gravity, which made it so controversial for a brief period, was 2020-era dissent, a then-homeless centrism doubly pledged to anti-covid-mandates and anti-trans ideology. My own sensibility is perhaps illegible to both the left-liberal literati and the reactionary centrists, as I attempt to synthesize elements of both their worldviews into something that will be more adequate to the increasingly strange demands of this century. (I know I don’t always succeed. See, for example, Mary Jane Eyre’s one-year-Substack-anniversary post. Nobody asks the hard questions like Mary Jane. By comparison, my conclusions are only convenient elisions.) Both “sides,” I assume, have their own reasons for hating (for example) this type of analysis of the Trump phenomenon. But if we can’t wrestle sympathetically with both the revolution in gender identity and the emergence of a highly stylized populism that have occurred over the last decade—if all we feel is a blank and harassed antipathy in the face of either or both these facts—then we may be exhibiting, if I am not totally mistaken, philistinism in the Wildean sense of the word:

The Philistine element in life is not the failure to understand art. Charming people, such as fishermen, shepherds, ploughboys, peasants and the like, know nothing about art, and are the very salt of the earth. He is the Philistine who upholds and aids the heavy, cumbrous, blind, mechanical forces of society, and who does not recognise dynamic force when he meets it either in a man or a movement.

And this may, if I’m not totally mistaken, cause one to unsubscribe to my Substack!

I enjoy the way this answer contradicts the one immediately above. For why that’s not a problem, you’ll have to listen to my upcoming Whitman episode. I contain multitudes, bruh.

I'm excited to buy this one!

I saw one of the advanced copies at my local bookstore! I naively asked if it was for sale haha worth a shot.