A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I posted “A Hideous and Intolerable Allegory,” part two of a three-part series on Moby-Dick in The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers to this Substack. This episode may be of special interest to aspiring writers as we used the occasion of Melville’s self-described “botch” of a novel to ask how much aesthetic and philosophical unity a novel or any other work of art actually requires. We will wrap up Moby-Dick next week and then move on to the “father” and “mother” of American (perhaps of modern) poetry, Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson. Thanks to my paid subscribers, and to those who aren’t yet paid subscribers, you have a burgeoning archive of discourse—19 weeks on British literature from Blake to Beckett, eight weeks on James Joyce (with a focus on Ulysses), and four weeks on Eliot’s Middlemarch, in addition to our ongoing American literature survey1—awaiting you. Please subscribe today!

The official release of my new and forthcoming novel Major Arcana is also bearing down upon you like an angry leviathan. It comes out from the distinguished Belt Publishing on April 22, 2025 and can be pre-ordered here. Pre-orders will testify to the strength of independent literature—a bold and free literature that is intensely imaginative about the present—in our otherwise timid time. Substack’s (and the New York Times’s) own Ross Barkan has called it “perhaps the elusive great American novel for the 21st century,” while the legendary novelist and screenwriter Bruce Wagner has said that “to read it is to hold the heart of the world in one’s hands.” (If you can’t wait until next spring to “hold” it, paid subscribers to this Substack can also access the original serial of the novel, complete with my audio rendition.) Thanks to all who have read and reviewed the novel so far, and thanks to all who have pre-ordered!

For today: Eliot Weinberger, Tu Fu, Fredric Jameson, Katherine Dee, and the role of the public persona qua poet in political discourse. Please enjoy!

Live Like a Wren: The Poet and the Persona as a Work of Art

A few weeks ago—recalling friend-of-the-blog Alice Gribbin’s Manifesto! podcast appearance earlier this year2—I impulse-bought Eliot Weinberger’s The Life of Tu Fu in a bookstore. After friend-of-the-blog BP alerted Substack Notes of the depressing news that Weinberger was writing dime-a-dozen spittle-flecked political polemics in the London Review of Books this week, I actually read The Life of Tu Fu last night.

I’m not a Weinberger expert. I knew him mainly as the editor of Borges’s Selected Non-Fictions, one of the 20th century’s most indispensable collections of “nonfiction,” especially because the Argentine mage exposes the inherent fictionality of this very category.

But, as someone whose politics were forged in the years between the fiery catastrophe of September 2001 and the watery catastrophe of September 2005, I also knew Weinberger as the author of “What I Heard About Iraq.” This is a classic of what we might call documentary argument, a prose-poem collage of extraordinary restraint and understatement, allowing the obscene to speak for itself via its lucid and unruffled exposure:

I heard the vice president say: ‘By any standard of even the most dazzling charges in military history, the Germans in the Ardennes in the spring of 1940 or Patton’s romp in July of 1944, the present race to Baghdad is unprecedented in its speed and daring and in the lightness of casualties.’

I heard Colonel David Hackworth say: ‘Hey diddle diddle, it’s straight up the middle!’

I heard the Pentagon spokesman say that 95 per cent of the Iraqi casualties were ‘military-age males’.

I heard an official from the Red Crescent say: ‘On one stretch of highway alone, there were more than fifty civilian cars, each with four or five people incinerated inside, that sat in the sun for ten or fifteen days before they were buried nearby by volunteers. That is what there will be for their relatives to come and find. War is bad, but its remnants are worse.’

I heard the director of a hospital in Baghdad say: ‘The whole hospital is an emergency room. The nature of the injuries is so severe – one body without a head, someone else with their abdomen ripped open.’

To this composition, powerful in its very reticence, we might compare Weinberger’s most recent “essay”—the term hardly applies, since it’s not a searching attempt but a drubbing homily—with its conviction that its certainties are apodictic:

The Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, when Biden was still in the race, had been his triumph. He had – it is astonishing – completely purged the party. Almost no Republican who was prominent fifteen years ago showed up, nor did his own former vice president or most of the former members of his cabinet. Instead they had aged wrestlers, obscure rockers, Z-list actors, a star of the ‘adult’ website OnlyFans and the Twitterati faction of Congress addressing the flocks of red-crested warblers in their MAGA caps. Dizzying for those of us who grew up in the Cold War, this was a Republican Party that was now the enemy of the FBI, the CIA, Nato, the Department of Education and Walt Disney, and was the ally of Russia.

I am not going to write an answering tirade here, but I do want to say that the final sentence of the above passage requires circumspection, not knee-jerk polemics, from those like Weinberger and myself who have long been skeptical (for example) of the CIA. Like the apparently self-justifying slight en passant of a sex worker, the formulation “ally of Russia” is also a Bush- or Cheney-like “with us or against us” over-simplification. This is not an apology for Trump, but rather a reminder that the strongest case against Trump on foreign-policy grounds, as made by leftist and libertarian commenters like Michael Tracey, Caitlin Johnstone, and Thaddeus Russell, is that his foreign policy in practice often was and threatens to remain largely indistinct from that of Dick Cheney, despite the mogul’s sometimes more pacific rhetoric, rhetoric that should be cautiously encouraged and not vulgarly derided in War-on-Terror terms. To say this, however, is necessarily to transcend election-year op-ed writing even in political argument. Shouldn’t a poet be above such cheap rhetoric? A poet of Weinberger’s stature? A poet who can write The Life of Tu Fu?

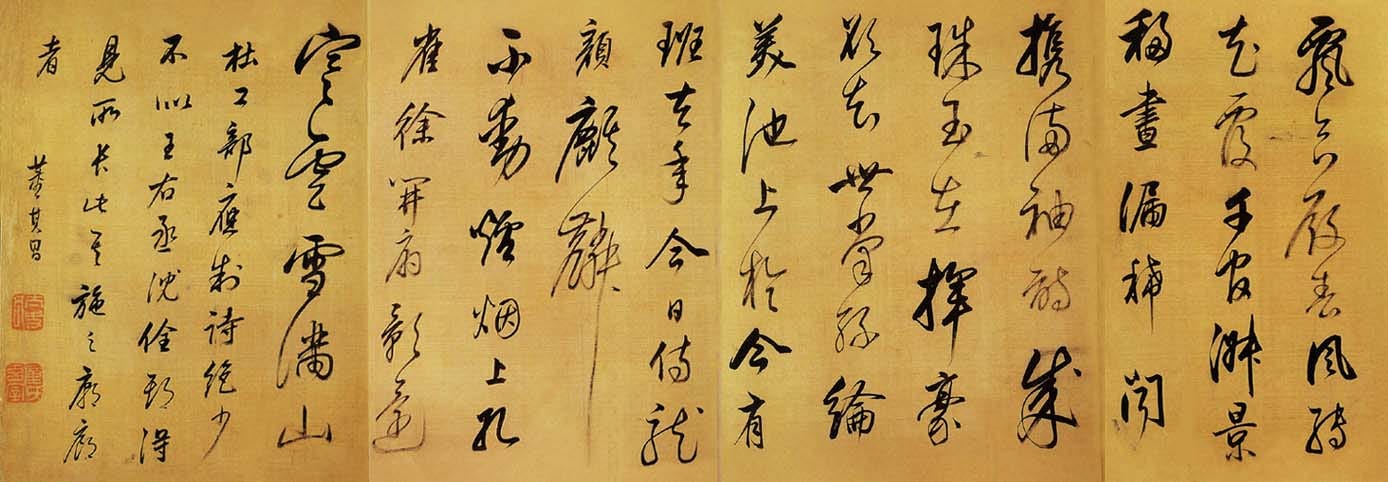

I love The Life of Tu Fu. A long poem comprised of Weinberger’s montage of themes, images, and quotations from the tumultuous life and crystalline work of the Tang Dynasty poet, it’s not my kind of book. Part of me wants to make fun of it for being, like Byung-Chul Han’s texts, vended by the publisher at full-length book price while scarcely (if I had to guess) containing 15,000 words. It’s also not my aesthetic. As a writer and a reader, I like to find the subtlety lurking in overstatement rather than the passion buried in understatement.

And yet, as I’ve said, the danger of criticism is becoming imprisoned in one’s own taste, an increasing parody or caricature of oneself. You run the risk of armoring—and thereby immobilizing—yourself in an aesthetic theory that prevents you from appreciating beauty and vitality wherever they arise. The Life of Tu Fu is not my kind of book, except that is a book of moving gravity and mordant levity, a book about the perception of fleeting beauty in a world of war and disaster, about endurance amid the loss of love, the loss of vigor, the loss of the present. It is about the way the simplest of words can evoke the largest of realities. It is the book of all our lives, which means that it is my kind of book, and maybe also yours. I’m glad I bought it, and I’m glad I read it. Early on, Weinberger or Tu Fu laments,

On either side of me, people take strong positions and never agree.

I have a hard time remembering what anyone says.

Why, then, take one’s place on “either side” among these forgettable disputants in these forgettable disputes?3 Why, when you know what really matters, what really strikes deepest?

Soldiers still guard the ruined palace: rats run across the tiles.

A squirrel with folded hands outside his broken nest.

That dandelion in the wind once had roots.

Live like a wren, unnoticed on a high branch, and you’ll stay alive.

It’s been so many years: I imagine her face, looking at me skeptically.

The poet suggests from time to time that the role of art in a world torn from its roots by politics is not to take a political side but to demobilize or simply dissolve world-wasting political passions, to be attentive to experiences other than the political (“You’ll weep for reasons other than the war,” the poet warns), and to model an entirely different and more humane form of order:

I thought of Fu-tzu Chien: when he was administrator of Shanfu, he spent the whole time playing the zither and the city was well-governed.

[…]

I thought of Liu K’un. Surrounded by enemy troops, late at night he climbed a tower and played sad songs on a reed pipe. The soldiers, overcome with homesickness, abandoned their posts and the city was saved.

Here we recognize what I was discussing last week, the view of art as repository of utopian longing smoldering beneath the everyday struggle, an aesthetic emerging from German Romanticism4 in figures like Hegel and Schiller and still alive, if deformed by the threat of totalitarian force, in a Marxist critic like the late Fredric Jameson. In Leo Robson’s appreciation of Jameson as appreciator I linked last week, he quotes the critic as follows:

Art allows us to walk all around these otherwise latent and implicit unconscious attitudes which govern our actions; to see them isolated as in a laboratory experiment for the first time, spread out and drying in the light of day where we are free to evaluate them consciously. This explains why the writer’s personal attitude towards that ideological material is not so important, why it does not ultimately matter whether Balzac was a reactionary, or whether Mailer is a sexist, a dupe of the myths of American business, and so forth. For his essential task as a writer, faced with such ideological values both within and without himself, is, through his own prereflexive lucidity about himself and through the articulations of his fantasy life and the evocative ingenuity of his language, to bring such materials to artistic thematization and thus to make them an object of aesthetic consciousness. After that has been accomplished, his own distance from the ideological object in question is no more privileged than ours, with which we are free to replace it.

This, I believe, is also the insight enacted so beautifully, so lovingly, by The Life of Tu Fu. I also believe that artists as public personae should carry enact this insight in their public performances. As friend-of-the-blog Katherine Dee observes in a characteristically perspicacious new essay, “No, Culture Is Not Stuck,” the online persona is one of the new art forms of our time:

The social media personality is one example of a new form. Personalities like Bronze Age Pervert, Caroline Calloway, Nara Smith, mukbanger Nikocado Avocado, or even Mr. Stuck Culture himself, Paul Skallas, are themselves continuous works of expression — not quite performance art, but something like it. They may also be influencers, or they may not be, but the innovative aspect isn’t that they're promoting a brand or making money from their venture. It’s not about their single tweet, self-published book, or video. The entire avatar, built across various platforms over a period of time, constitutes the art. Their persona must be enjoyed in the moment, as it reveals itself on the platforms; the audience response is part of the piece. The way their audiences start to speak like them, the aesthetics they inspire, and the way they shape headlines — this is all social media born culture.

Unlike Kat, I believe (or hope) that literature will not so much be surpassed by the online persona as it will be saved by being harnessed to the online persona’s energy, a latent possibility since the early-celebrity days of Rousseau, Goethe, and Byron. That is why I write my online persona into being as surely as I write my novels into being, each augmenting and advertising the other. But this strategy will only work if the author of the online persona remembers that the world-transcending energies of art must operate in the online persona itself and not just in the online persona’s offline artworks. Made of words, we are poems. Our political interventions, therefore, should also be poems. The writer of “What I Heard About Iraq” once understood this; I hope we can all, in the most divisive of American seasons, come to understand it, too.

The four little pines I planted are choked with vines. The fish are not biting and the deer just run off and don’t bother to look back. There’s no path to my cottage, but I’d clear one for you. When melons get ripe in the fall, I think of you in Melon Village. How are the melons this year?

I insert here my regular reminder for newer readers that I also have a YouTube channel featuring 60 pandemic-era lectures prepared for university courses on Multicultural Literature of the U.S. and Contemporary American Literature, all of them free, for anyone who finds The Invisible College’s selections excessively consecrated to old white Dick.

This appearance inspired a Weekly Reading post about the contest in American poetry between Wallace Stevens and Ezra Pound. (Weinberger is basically a Poundian.) An earlier Weekly Reading post concerned a similar dichotomy in American fiction between Melville and James. In each case, I was concerned to resolve the antinomy rather than taking a side: I discovered in Pound a figure as imaginative as Stevens and in James a writer of equal visionary stature to Melville. As a novelist, I observed, I tend to write in a Melvillean style (operatic and symbolic) about Jamesian themes (the subtleties of art and interpersonal relations), and, as an essayist if not as a poet, in a Stevensian style (ironic and rococo) about Poundian themes (the fate of civilization). I raise these matters for the benefit of matriculates in The Invisible College since we can trace these later conflicts back to the primordial one between Emerson with his “self-reliance” and Poe with his “imp of the perverse,” episodes upon which writers are already available in the archive. We are almost finished with Melville and have episodes on James, Pound, and Stevens, among others, upcoming. Were I a political scientist, I might observe that this fault-line in our literature resembles the one still earth-shakingly active in our politics between the party of Jeffersonian populism (Emerson, Melville, Stevens) and that of Hamiltonian elitism (Poe, James, Pound), but the analogy is imperfect, and I don’t know the history well enough.

“But John,” it will be objected, “you sometimes write about politics.” I do, but my aim is to use this peculiar form of theater—much as it may strike out and kill the audience occasionally—as another locus for investigating the complexities of human nature, not as an occasion for moral grandstanding, nor even for policy recommendations, which I mostly don’t have. Insert here, then, another “incendiary footnote” I’ve been mulling for almost a month in response to Sam Kahn’s “The 2024 Election Is a Gender War.” It is, but not the way it’s conventionally discussed, given the way gender has so radically been revised in our time, a time when men and women apparently want to become each other more than ever before in human history. The full footnote would begin with the concluding speculation of a remarkably ambitious and centuries-spanning 1998 essay on literature, pop culture, England, America, gender, and empire by friend-of-the-blog Nancy Armstrong—

When we recall that the cultural logic of the captivity narrative was originally American and remains in important ways an indelibly diasporic logic, however, it becomes all too apparent why this narrative always required an Other in the form of a source of pollution capable of eroding our cultural identity. Even after the culture held captive has become the dominant culture, the captivity narrative represents that culture as a culture on the defense. Compelled by its own logic to expand the domain of capital, this culture defines its distinctive values in precisely other than economic terms and imagines those values as perpetually in danger. For this culture imagines itself in a feminine position under conditions of cultural warfare, in which the purity of its women, the safety of its children, and the sanctity of its basic unit, the household, are up for grabs. This is no less true for England and the United States under conditions of globalization, instantaneous communication, and hi-tech warfare, than it was during the epochs of Richardson, Austen, and Brontë. What is not so clear is what will come next, after the merger of the phallic woman and the post-oedipal man.

—and go on to explicate how the 2024 contenders, with their rival but increasingly convergent captivity politics as she hurries to the right on immigration and he to the left on abortion, exemplify these archetypes: the phallic woman who promises to shoot intruders dead vs. the post-oedipal and perforce post-phallic man of écriture féminine (some call it “the weave,” weaving being traditionally women’s work). But the point of such a discourse would be to explore reality in all its painful contradictions and beautiful paradoxes and unexpected developments, not to advocate for a political position, especially when the available positions are increasingly narrowing, increasingly unacceptable to those who’d hoped for anything more. In any case, I’m not going to write that essay. As Katherine Dee also instructs, nouvelle vaudeville has succeeded literary discourse, and one viral TikTok is surely worth more than 1000 words:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

I assume Weinberger is hostile to Romanticism, however. One gnomic line in the The Life of Tu Fu, whether or not it was written originally in Chinese in the eighth century or not, strikes me as a direct rebuke of William Blake for his presumptuous imprecision as would-be prophet: “If it is not painted perfectly, a tiger will look like a dog.” I am thinking also of Weinberger’s exceedingly negative review of Gabriel Josipovici’s What Ever Happened to Modernism?, a book I conversely admired. Weinberger writes:

In fact, these supposed hallmarks of the Modernists may be found at almost any moment in history. If his worldview were not so obstinately Eurocentric—even the entire Western Hemisphere has only two exemplars: the faux Englishmen Borges and Eliot—Josipovici would have found China, to name only one, full of his kinds of Modernists. Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, 2,500 years ago, were talking about the inadequacies of mere words, of a language beyond words. Classic novels such as Golden Lotuses (The Plum in the Golden Vase) or The Story of the Stone (The Dream of the Red Chamber) played games of illusion and reality with the reader as complex as any in Cervantes. And the innovations that he finds in Wordsworth and Caspar David Friedrich—placing the observer in the scene of nature, and the realization that “vision is always vision at a particular moment, from a particular place, and that though vision may be the goal it does not subsume life but is only one moment, one experience, within life”—seem applicable to nearly the entirety of Chinese poetry and landscape painting.

[…]

Ultimately, Josipovici’s Modernism is entirely interior, the result of a few ideas and much agony, despair, and self-doubt. He dismisses as “dreadful” and “positivist” histories of Modernism that take into account what was happening physically in the world. But artists and writers are alive in certain places at certain moments, and there is no doubt that, since the mid-nineteenth century, their work has issued from and responded to the enormous changes around them.

It is another case of Pound vs. Stevens. Weinberger reproves Josipovici for his essentially Romantic conception of modernism as a subjective affair of post-Protestant consciousnessness, when for Weinberger modernism must “contain history,” including political and technological history, and also be more multicultural than the supposedly Eurocentric Josipovici supposedly allows. (It seems not to have occurred to Weinberger that the Egyptian-Sephardic-descended Josipovici—the literally Alexandrian Josipovici—might be writing out of an “Orient” of his own, even if it is not identical to Weinberger’s “Orient.”) In any case, writers’ exclusions are worthy of critical examination and explanation and are always revealing, but, unlike Fredric Jameson, I don’t suspiciously take them as “symptoms.” Cosmopolitanism is good in principle, but every single person can’t write with authority or conviction about every single thing. If Cavafy means more to Jospivoci than Tu Fu does, then what of it? If one danger is becoming a caricature of oneself, an equal and opposite danger is becoming nobody in particular.

Always take my advice on art…

Great post. "I like to find the subtlety lurking in overstatement rather than the passion buried in understatement." < I see what you mean here but when the Poundian poem-including-history guys do this I always find it a bit risible. I don't really like Sebald or Labutut for this reason, you're reading about ancient China or cod fishing or whatever and there's a big neon sign in the middle flashing "THE HOLOCAUST" or "HIROSHIMA" -- it yokes the unclassifiable wonder and strangeness of the world back into the limitations of the European 20th century mind. A great strength of Weinberger on the other hand is he gives you the connections and you work out the meaning for yourself.

Also now that the dust has settled and Pound's direct inheritors are drifting out of the public consciousness a lot of his essays have this neat Borgesian quality -- a whole secret history of 20th century literature where we're all talking about Charles Olsen and Louis Zukovsky instead of Plath and Stevens. All these strange and lonely men laboring away on these gigantic, gnomic testaments. A lot of the actual output is too obscure to really be great but I never get tired of reading about them.

If anyone is curious I recommend all of his work but especially the gorgeous and unclassifiable linked essay/prose poem An Elemental Thing and the hard to find but entertainingly venomous early collection Written Reaction.