A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

The Invisible College is my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. Its month-long late-summer session on George Eliot’s Middlemarch heated up this week with an episode (“The Progress of Planetary History”) turning on the question of how to maintain ethics without God, the utopian promise extended by this greatest of English novels. Please offer a paid subscription to pursue the question through Middlemarch’s second half, not to mention 19 episodes on modern British literature from Blake to Beckett, eight episodes on the work of James Joyce, including Ulysses, and the upcoming fall series on American literature from Emerson and Poe through Stevens and Faulkner, including Moby-Dick.

To gamify your participation: I am currently making from paid subscriptions what I’d get for teaching three courses at a community college. Given the scale of this project, however—only one weekly episode so far has dropped below two hours, and that one by three minutes—let’s see, please, if we can get those numbers up to what I’d be making for three courses at a state university. After that, I aim for seven figures!

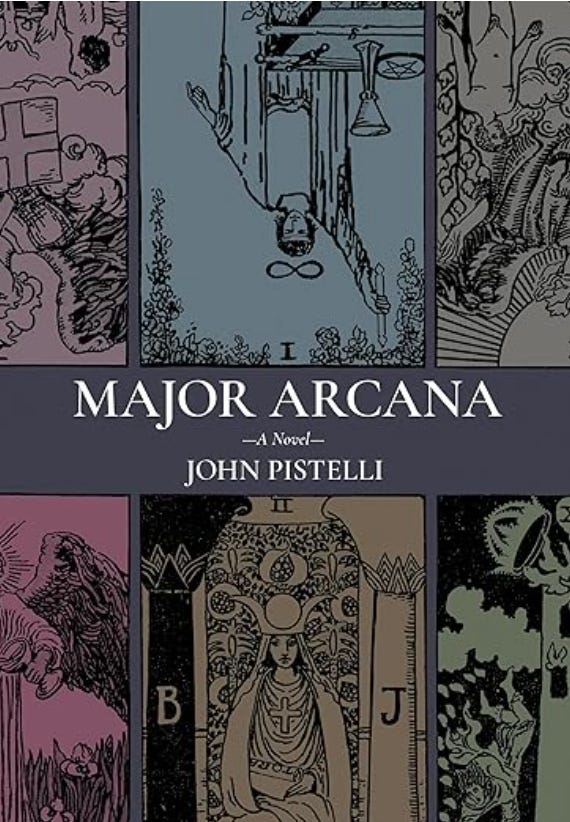

I also remind you that in April of 2025 the beautiful Belt Publishing edition of my new novel, Major Arcana, will be released. You can pre-order what has been called “perhaps the elusive great American novel for the 21st century” here, read comprehensive but spoiler-free reviews here and here, and read an interview with me about the book here. The success of this first Substack-serialized novel to garner a book deal will inspire more publishers to take the kinds of creative risks that Anne Trubek and Belt Publishing have so admirably taken, so pre-orders are appreciated.

Today’s post? On the one hand, I’d like to make each Weekly Reading the perfect jumping-on point for new readers, which I am currently gaining at some automatic or algorithmic regular rate. On the other hand, these Weekly Readings often seem most intense and compelling when I pursue a theme across multiple entries, when I chart for you the rise and fall of my thinking on some subject, just as I used to do when it seemed like almost nobody was in attendance. The latter option seems best for generating the type of particularity that attracts an attentive and appreciative audience; the audience doesn’t come to one just for one to turn oneself into a simulacrum of the average poster on their ostensible behalf. Therefore, back we go, for at least one more week, to the question of literary sociology. Please enjoy!

Dream On: Where Does Literature Come From?

I couldn’t help but notice the coincidental arrival in my inbox of two superficially unrelated and dissimilar Substack posts this week that nevertheless seemed somehow to answer each other: Joyce Carol Oates’s lecture “Inspiration, Obsession, the Artist’s Life” and friend-of-the-blog Julianne Werlin’s “World Literature, 1600.”

Professor Werlin reviews a recent work of scholarship (Ning Ma’s The Age of Silver: The Rise of the Novel East and West [Oxford, 2016]) comparing canonical early modern novels across cultures to arrive at the thesis that modern fiction in all its secularizing and dialogic tendencies is a response to the emergence of global commerce, in this case, the circulation of silver mined in Peru and turned into wealth in markets both East and West.

Werlin explains the methodological upshot of such a study: this type of comparative literature, attentive to comparable contexts, frees scholars from the burden of establishing direct influence if they wish to discuss texts from far-flung locales. Shared conditions, not shared traditions, become the warrant for comparison. It’s a powerful and productive idea. Without having read the book in question, though, I believe I can still say from experience that characterizing the kind of “response” literature makes to economic or social conditions remains a problem of its own.

What is a novel? Is it the accompaniment, the complement, the effect, or the agent of market economies—or any other of its contexts and conditions? In real life, as opposed to theory, it’s all four at once, I’m sure, plus a few more. Where we place the emphasis, however, matters. Werlin expresses in the comments an disinclination to view literature as an epiphenomenon of other forces, a disinclination I share. It’s very difficult, though, even for someone with my biases and (yes!) interests, not to do this.

Where does literature come from? The answer to this question will answer the question of how to secure the authority of literature, since the authority of literature is all that can possibly secure the authority of literary institutions. The problem is most evident with respect to academe, but flows from academe out into publishing, journalism, mass entertainment, secondary and primary education, and more. As I’ve said before, if literature has no intrinsic authority, if it is simply the effect of historical or social or psychological or biological forces, then literature departments are a waste of time and resources, and the study of literature should therefore be folded as a minor sub-field into the relevant disciplines.1 As literature, through English classes down to the grade level, is the foothold of art tout court in common education, then a merely epiphenomenal art can be socially demoted as either mere time-passing entertainment or explicit moral instruction, rather than extolled (in Schillerian terms) as a unique and uniquely generative frame of mind whose purchase on the world is more comprehensive than that of other and more reductive discourses. I don’t especially care anymore what happens to the English department, but its collapse portends or exemplifies (even here: the problem of causality!) a much more general collapse. Joyce Carol Oates writes about what is at stake in the lecture linked above:

I believe that art—in its varied forms—is the highest expression of the human spirit. I believe that we are united in our yearning to transcend the merely finite and ephemeral; to participate in something mysterious and communal called “culture”—and that this yearning is as strong in our species as the yearning to reproduce the species.

The easiest and most intuitive way out of the dilemma is to grant authors the agency robbed them by French Theory, which identified the text as an effectively authorless weave of circulating discourses temporarily collocated, if anywhere, in any given reader’s or readerly community’s experience of textuality. If texts are a response to conditions, then authors as makers of texts are the source of the response and the proper object of study. And if literature comes from authors, then their (even our) intentions return to the fore as the focus of investigation and the locus of authority.

The authorial solution won’t work, however, and for several reasons. First, everyone who is even a moderately experienced reader knows that authors are not in full control of either the meaning or the effect of their work, thus the persuasiveness in the first place of concepts like “The Intentional Fallacy” and “The Death of the Author.” Second, as flawed individuals, authors cannot bear the ethical burden of such scrutiny, and, if they’re made to, literary study will become a referendum on their personalities and activities.2 The price of cashiering history and sociology will be to elevate psychology and biography in their place. Even if we put aesthetes in charge, the resulting error will be the one made on the MFA side of the English department: redefining literature as a craft, like carpentry or cooking.3 I know I am publicly identified with the aesthete position, but here aestheticism can’t help us either, is just another way of artfully dodging the question by referring it to form, when the origin of form is the problem in the first place.

Perhaps authors should have no say in the matter—you wouldn’t hire an elephant to teach biology, as Roman Jakobson famously quipped—or perhaps the modern university, with its mandate to advance secular Wissenschaft and inculcate secular Bildung in service to the nation-state, never was going to be safe home for art. That is my only apology for what I am about to tell you, which is what every author knows, and what Plato, Dante, Blake, Shelley, Emerson, Woolf, and Morrison have already told you, quoted ad nauseam in these electronic pages: the best work is channeled. Alan Moore: “It seemed to me that creators should not confuse themselves with whatever light comes through them.” Those names are old favorites, but I heard new favorite around here, Bruce Wagner, say this on some podcast or other: the writer’s main job is to get out of the way.

As Oates has it in the lecture linked above, then, the writer is “inspired.” Oates surveys a number of authors all of whom testify that a spark from somewhere else produced the conflagration of their work. She adduces Emily Dickinson, of course—but that recluse can be dismissed by the inveterate skeptic as merely mad. What about Mary Shelley and Robert Louis Stevenson? Oates records that their horror stories came to them in dreams. “But who can rely on dreams, and who cares about 19th-century thrillers?” I imagine the skeptic rejoining.4 Is it more persuasive to a skeptical audience when Oates gives as exempla not only the despairing Beckett, who said “It all came together between the pen and the hand,” but even the master of craft himself, Hemingway, whose struggle toward “one true sentence” was nothing other than a struggle toward the proper posture of authorial receptivity to inspiration?5 I don’t know; I didn’t need to be persuaded in the first place, because I have experienced what happens in dreams and what happens between the pen and the hand; I am just trying to imagine how someone like Roman Jakobson might see it, since, as Oates also points out, not everyone is regularly inspired. If an elephant could speak, would the biologist understand?

What if the object of literary study, then, were neither author nor context but the source and effect of this inspiration itself?6 Would we be carried too far outside the secularizing remit of the university or of the market? Would we simply find ourselves, once again, in the wilderness?

If literature is the agent of social change, on the other hand, it has an undeniable authority but probably much less authority than more obviously agential texts, such as laws, political discourses, or works of mass culture; therefore, it belongs as minor subfield to rhetoric. Establishing this latter idea was more or less explicitly the goal of the theory set in the late 20th century, as the more manifesto-like passages of Terry Eagleton’s broadly influential Literary Theory indicate. See my essay on Eagleton’s book for an impassioned criticism of this idea. Eagleton’s later refutation of Dawkins-style New Atheism redounds, it should be obvious, on his own corrosive skepticism and materialism in the matter of art. I have neither the space nor the expertise to develop a counterargument here, but surely the Catholic phenomenologists—I have a very dim recollection of reading Jean-Luc Marion in graduate school—would make a relevant riposte to such skepticism and materialism, something to the effect that the inspired artwork is a manifestation of the givenness of God’s abundance in the world.

These two objections are interrelated: for example, what do Alice Munro’s works mean now that we know she was a pedophile’s accomplice? They mean more than they did before, and in a way illicitly thrilling to any dispassionate investigator who is being honest about it, but we hardly want to give her any credit for that fact.

Crafts aren’t even crafts in this connotative sense of practical mastery over a task requiring fine motor control, hence the compliment frequently paid to carpenters and cooks that their best work is made with “love,” or, to anticipate my argument, with “inspiration.”

For me on dreams and literature, please see here. Oates ends with a rumination on the hippocampus as neural analogue to art’s function, i.e., the repository of long-term memory and therefore identity. Nobody really knows anything in this area, but I tend not to be persuaded that consciousness resides in the brain; the best that can be said is that the brain is a receiver for whatever it is that consciousness happens to be. If it were not, where do dreams and inspirations come from in the first place? By instinct, I stand with Homer, Plato, Jung, and most cultures before the rise of psychological science, and believe it comes from outside the self. Freud thought dreams and inspirations came from the inward depths, which is fine if those are an inlet for outward depths. But Freud only raised the issue of the “oceanic feeling” in Civilization and Its Discontents—a phrase he borrowed from a letter of Romaine Rolland’s—to claim he never felt any such thing as a prelude to dismissing it as a psychic recrudescence of our sojourn in the amnion.

(I try not to be unduly judgmental, but he never felt it? Never? Not even when he was first in love? Not even when he read Shakespeare, Goethe, Dostoevsky? Not even—I am being comically literal here, but also perfectly sincere—when he went to America by steamship and therefore crossed the ocean? The actual ocean, perhaps the most mysterious of all the entities we share the earth with, something that makes my stomach drop with awe and terror just to think about, did not inspire the oceanic feeling? If I were to arrogate to myself the psychologist’s power to judge individual and therefore social health, I would question the fitness of such a sensibility to make any judgments in this area.)

See also Gordon White’s latest podcast with Phil Ford and JF Martel of Weird Studies, an extended conversation about “non-human agency” in artistic creation. As Martel in particular notes, the idea of “genius” was originally devised to capture the action of this agency, not to honor the artist as a great man or gifted individual. Thus, contra Dan Sinykin and the several generations of Marxist scholars standing behind him, genius is not only not a liberal or capitalist idea but was rather an idea forged as remediation for the damage capitalist and liberal rationality caused the individual and collective psyche. Writers like Shelley and Emerson deserve more credit for using this idea not to demolish but to supplement and fortify liberal civilization, when it could very easily have gone the other (we might say the German) way.

“German”: here would be the proper place for an essay on the controversial “Hegelian egirls,” were I equipped or inclined to write one. Suffice it to say that, insofar as I understand their jargon, I essentially agree with their goals, except that trying to accomplish their promised sublation of today’s contending ideologies on the ground of political argument itself isn’t going to get anywhere, because people are literally conditioned by all-consuming and abusive media to be, as Hegel would say, “one-sided” in current politics. (One could tell you, for example, that one was literally subject to Tim Walz’s pandemic governance in 2020-22, and therefore that one would not vote for this totalitarian Teuton’s accession to any office whatsoever even if one were held at gunpoint, but you’d only get mad at one and not hear any other word one had to say. One probably wouldn’t even blame you.) In other words, yes, liberalism always and desperately needs to integrate its fascist shadow—Jungian psychology is also dialectical—rather than projecting it outward everywhere onto internally or externally imperialized subjects to be dominated or vanquished, but the locus for this integration can’t be the political itself; otherwise, as Auden said in The Prolific and the Devourer, the only way to fight fascism will be to become a fascist oneself (this has almost been the explicit mission statement of the left for the last decade; it’s a little late to be bellowing about “freedom” now). I wouldn’t parochially insist on art as the sole means of such therapy—religion and spirituality, for example, would be another, as would the encounter with nature, whether scientific or “lay”—but politics alone can’t save us, and politics in itself depends on those other powers that can. On the other hand, the demagogic jump-scare style of political writing designed to further fleece a frightened audience by finding a way to leap out and shout “fascism” at the end of every essay, as if historical semantics were really the issue here—yes, I’m talking about John Ganz, but not only about John Ganz—is worse than useless, is a compounding of the problem. I could criticize comparable right-wing pundits for the same reasons, up to and including J. D. Vance, the other totalitarian VP candidate, but I suspect literary people already know that argument by heart and therefore need more urgently, not to say dialectically, to attend to the other side. Anyway, Hegel’s too hard to read and my essay on Hegel (written in a state of near-panic under lockdown) isn’t worth reading, but my essay on the Hegelian Gillian Rose and my essay on the Hegelian Francis Fukuyama may shed some light, as much light I can shed, on these concerns. Rose, in particular, though not electronic, and a woman rather a girl, is probably the author I’d recommend right now if I knew anything about Hegel and Hegelians:

I bring the charge that reason’s claim remains unrealised from the transcendent ground on which we all wager, suspended in the air.

The conventional gender polarity of the examples—Dickinson at the feminine extreme, Hemingway at the masculine—plus the gendered polarity between the receptivity of the authorial mind and the activity of the authorial pen leads us into further questions. One meaning of Woolf’s contention that authors must be androgynous is that they must be both receptive and active, each in the proper moment. Because extremes become their opposites, we recall that Hemingway was girlish in bed while Dickinson in one of her best poems recalls what happened to her “when a boy and barefoot.” See my polemic against the wretched Franco Moretti for the effect of overvaluing the masculine in literary sociology; I didn’t make the point in such explicitly gendered language, but my objection to the obscurity of Susan Howe’s celebrated My Emily Dickinson might hint at the problem with an overvaluation of the feminine. Finally, here and elsewhere, not least in Major Arcana, I understand masculine and feminine to be psychic (even cosmic) forces, never wholly or seamlessly embodied by any given human person, and never lived out by any person except in some easy or uneasy and ever ongoing synthesis.

Listeners to The Invisible College will testify that I don’t focus on such metaphysical concepts either, that I talk as much about social context and the like, even about psychological motivation, as anybody I might seem to be criticizing here. The present speculation is only aspirational. As for the question to which I’ve attached this footnote: literary history offers one example that I can easily think of outside New Age publishing, which is Jorge Luis Borges’s recently translated and marvelously eccentric course on English literature. (He leaps from the Anglo-Saxons to Samuel Johnson, for one thing.) Professor Borges’s college was a lot more invisible than mine is. I wrote about it here:

Borges’s lectures do not look obviously impressive—they consist of biography, context, and redescription of the text under discussion, with little in the way of 20th-century hermeneutics—but taken as a whole, they may amount to an attempt to discredit the very idea of “culture” (in the sense of the organic expression of ethnic identity) in favor of “literature.” What, to Borges, is literature if it is not the spontaneous effusion of blood and soil?

One answer may be “inspiration.” Early on, Borges discusses the earliest English poem, Caedmon’s hymn, a poem dictated to a monk in a vision. He traces this Caedmon theme, then, through the dream that led Coleridge to write “Kubla Khan” and the dream that led Stevenson to write The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Some of the best literature, in other words, descends upon the poet from well above the cultural realm—from some invisible world.

I'm reading the new translation of the Iliad rn and it's interesting how, when the gods send people dreams, the dreams themselves are personified like Ariel from The Tempest ("hearing these words, the dream dashed off at once"). That + this post bring to mind how even the driest and most rational fields stand on irrational pillars, like how the scientific method, the periodic table, and the structure of the atom all have their origins in dreams.

There is something to be said for the study of literature as, not a subfield of history per se, but a sort of communion across or inside history. When you read something like The Iliad ofc there are recognizable expressions of big emotions, fear, grief, rage etc but by the peak of the age of the novel you get the penetrating eye of someone like Tolstoy who can put you in a society that feels very alien in certain ways but then describe a tic, a passing feeling, a little annoyance that's identical to something you felt yesterday (and I'm having a very similar experience with Eliot as well). And that moment of recognition shocks you into realizing that the people living then were as fully human as you are now, which is as important to historical study as the monographs on grain production and whatnot.

"If literature is the agent of social change, on the other hand, it has an undeniable authority but probably much less authority than more obviously agential texts, such as laws, political discourses, or works of mass culture; therefore, it belongs as minor subfield to rhetoric. Establishing this latter idea was more or less explicitly the goal of the theory set in the late 20th century, as the more manifesto-like passages of Terry Eagleton’s broadly influential Literary Theory indicate."

Yeah, this proved to be the worst possible solution for exactly the reasons you say. In trying to treat literature as an agent of social history, it made social history, rather than literature, the primary object of analysis, even for scholars of literature. As soon as people realize that literature has less of a claim to shape the nature of the state than the army or the legal system or tax collection (which is not that hard to do), there's no longer any reason to read it. In more straightforwardly materialist accounts, at least literature remained the object of study, even if such studies couldn't explain its value. So long as its value could be taken as axiomatic, though...