A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Major Arcana continues, nearing 80,000 words, serial to come on the vernal equinox. The best description of novel-writing as an experience is Faulkner’s folksy “like trying to nail together a henhouse in a hurricane”—in other words, piecemeal precision work undertaken in an unrelenting bombardment of emotions and ideas. Political trepidation, too. Have I mentioned that Major Arcana will not shy from the complications of gender in our time—gender over the last several generations, in fact—and in a way I fear will leave one half of the audience calling me a filthy degenerate and the other half a dangerous ideological derelict? Not to mention anxiety of expertise: will I teach myself the whole of the Tarot before I finish writing a novel I’ve so recklessly titled Major Arcana? Probably not, but I enjoy pulling a card every morning. I got The Wheel of Fortune today, which I take to mean among other things that you will all be pledging a subscription, so thanks in advance. On the good days, I know am I writing the 21st century’s Doktor Faustus, and to those who would lament that the 21st century’s Doktor Faustus is about a comic-book writer rather than about Schoenberg, I can only reply, “Don’t blame me, babe, blame the 21st century!” On that note, here follows something I really don’t want to write but feel I probably must.

Exiles: Notes Toward the End of the English Major

Let’s talk about it: the New Yorker’s endless article on the death of the English major. I don’t want to talk about it—and the article was so long it made me as illiterate as a Harvard undergraduate, so I may only have skimmed the back half—but since I have sat and even knelt by the deathbed, my testimony may at least be amusing. I’m not sure I can gather my thoughts into a proper essay, though, hence “Notes Toward.”

First, my credentials. Between 2000 and 2004 I earned a B.A. in English literature at the University of Pittsburgh; between 2006 and 2013 I earned a Ph.D. in English literature at the University of Minnesota.1 Between 2007 and 2021, first as a graduate instructor and then as an adjunct professor, I taught the subject, and in fact often taught Textual Analysis, the course intended as an introduction to the major, an inculcation of its methods and procedures.

In the spring of 2021, I was informed on Zoom by an associate professor who had never met me that, irrespective of my performance, my services would be no longer required due to a confluence of factors, from declining enrollments and pandemic-era budget trouble to the problem of observers looking at the then-current adjunct cohort, of which I was a member, and wondering, “Where’s the diversity?” That last phrase is verbatim. She had, I repeat, never met me and knew nothing about me.

What did my students learn about what English majors did when I used to teach Textual Analysis? In common with most other instructors who taught the course in the department, I usually structured the class as a parallel survey, one of the major genres, usually in the order poetry → fiction → drama → film, and the other of modern literary theories keyed to the genres they best served, usually in the order New Criticism → deconstruction → psychoanalysis → Marxism → feminism → race and postcolonial studies → queer theory → cultural studies. My literary exempla were drawn from a mixture of the old and the new high-culture canons—e.g., Shakespeare and Toni Morrison—with a general preference against popular culture as too easy a quarry for this type of investigation.

Two assumptions are concealed in this curriculum, one true, the other false—though both, as assumptions, should be tested:

The true: great works of literature (I will use this phrase without apology until I join the English major in the grave) are great—which is to say able to speak intimately to multiple audiences across space and time—only insofar as they are polysemous, able to answer the needs of every kind of interpreter and interpretive method.

The false: literature falls naturally under the intellectual control of extraliterary academic disciplines, whether philosophy, linguistics, sociology, or psychology, and/or under the extraliterary surveillance of a programmatic revolutionary politics.

I always wrote the course description carefully to signal my allegiance to the first assumption and my dismissal of the second:

This course is an advanced introduction to the content, concerns, and methods of English literary studies. We will read examples of the traditional major forms (poetry, fiction, drama) and watch one film while also surveying literary theory from Plato to the present. Throughout the course, we will pose formal, linguistic, theological, philosophical, ethical, political, psychological, and sociological questions to imaginative writing. In turn, we will be attentive to the limits of these concepts as they confront works of art whose complexity of meaning or intensity of feeling may elude final interpretation. As a writing-intensive course, moreover, this class will ask you to write literary criticism as well as to read it; we will focus on developing arguments, supporting them with evidence, and composing clear and eloquent prose. The word “text” refers to any arrangement of words or other communicative signs, from instruction manuals to political speeches to TV shows. If we privilege literary texts over others—“literary texts” being broadly defined as those that tend to invite more attention to the artful patterning of words/signs than to the message those words/signs communicate—it is because literature has long been considered among the most complex, intelligent, and affecting modes of textuality. Perhaps the ultimate question this course will address is whether or not this is the case; in other words, the histories, theories, and methods we learn here may help us to say why we should read literature at all.

There are enough reasons for the death of the English major to keep 10 or 20 coroners busy, but I would give priority to the discipline’s inability to grant literature both autonomy and authority. Already in the mid-1980s, Roger Shattuck wrote an essay called “How to Save Literature” (collected in The Innocent Eye: On Modern Literature and the Arts [1984]) and identified the threat as literary theory’s blithe and in fact treacherous welcoming of the social sciences as a conquering army through the gates of the English department.

I will reserve Shattuck’s salvation proposal for a footnote,2 but, if I can return to my own biography, I wrote my dissertation, Modernism's Critique du Coeur: the Novelist as Critic, 1885-1925, as an attempt to solve this problem by positing works of literature themselves as the only literary theory literary studies requires—not least because the so-called social sciences have systematically plundered their insights from imaginative literature and then usually forged them into weapons of political control, whether we consider the anthropologist riding alongside empire’s cavalry to identify the gods for confiscation or the psychologist branding the patient with a presumptuous and meretricious diagnostic label perhaps best left as an unsystemizable surmise of Shakespeare’s.

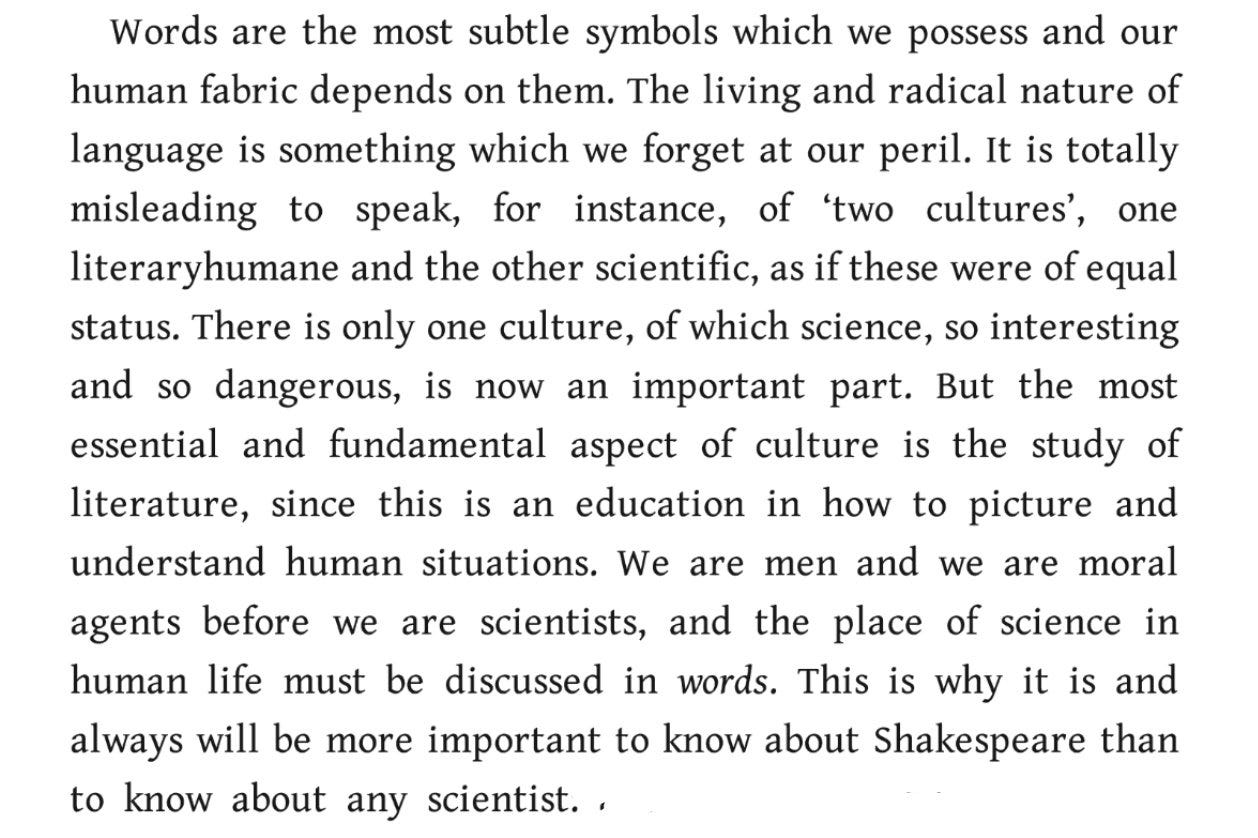

In the discipline of philosophy, I have found, some scholars call themselves “philosophical supremacists.” This Platonic concept means that philosophy holds intellectual priority over every other discipline from poetry to physics. I have met very few “literature supremacists” in literature departments, but I will wear the badge proudly (philosophy, like the social sciences, I regard as little more than poetry’s pale fire, though Plato himself I deem a poet). As I saw on Twitter, I will be in the superb company of Iris Murdoch.

The problem with my solution, however, may lie at the root: maybe any effort to formalize art—as much an affair of inspiration as of craft or cunning, of Plato’s “divine madness,” of Wordsworth’s “emotions recollected,” of Pater’s “hard gemlike flame,” of Joyce’s “epiphanies”—into an academic discipline will end by subjugating that art, exorcising or deconsecrating it, making it only one object among others subject to the academician’s objectifying and controlling secular eye. Maybe we are better in the wilderness.

Speaking of exile: among responses to the New Yorker article online, I single out two. First, Tablet editor Park MacDougald wondered if the death of the English major as announced in the New Yorker had anything to do with the decline of Jewish preponderance in American cultural life as announced where else but in Tablet. Second, playwright Matthew Gasda asserted, “harold bloom & george steiner were right about everything obviously.”

Obviously. Here, then, is Harold Bloom, from “Free and Broken Tablets: The Cultural Prospects of American Jewry,” collected in Agon: Toward a Theory of Revision (1982):

I will state now the gloomier element in my argument, the one that I desperately don’t want to believe. If American Jewry, of the supposedly most educated classes, assimilates totally and all but vanishes in thirty years, that is, except for the normative religious remnant, it will be because the text—all text—is dying in America, vanishing not into nature but into what Emerson grimly termed Necessity. A Jewry can survive without a Jewish language (and I will say something about this later in regard to Alexandrian Jewry and Philo), but not without language, not without an intense, obsessive concern that far transcends what ordinarily we call literacy.

In a Jewish tradition, let me consider the two alternatives. The more likely is that in thirty years America itself will cease to be a text, in the sense that Whitman said that “these States” were in themselves the greatest poem, or that Emerson wished to see each American as an incarnate book transcending nature. American Jewry, except for the normatively religious, will blend away into the quasi-intelligentsia, as in the fading lack of a textual difference between Yale’s more than 1,000 Jewish undergraduates and its more than 3,000 Gentile undergraduates. Though an elite, of sorts, neither “group” could fairly be termed a textual elite any longer. Yet no special education under Jewish religious auspices can affect the students I teach, because they are not open to it, not even in their pre-college years. For many reasons—social, technological, perhaps belatedness itself—it just is becoming harder and harder to read deeply in America.

And here is George Steiner, from “Our Homeland, the Text,” collected in No Passion Spent: Essays 1978-1995 (1996):

It follows, proclaim a number of rabbinic masters, that the supreme commandment to Judaism, supreme precisely in that it comprises and animates all others, is given in Joshua, 1, 8: “The book of the law shall not depart out of thy mouth; but thou shalt meditate therein day and night.” Observe the implicit prohibition or critique of sleep. Hypnos is a Greek god, and enemy to reading.

In post-exilic Judaism, but perhaps earlier, active reading, answer-ability to the text on both the meditative-interpretative and the behavioural levels, is the central motion of personal and national homecoming. The Torah is met at the place of summons and in the time of calling (which is night and day). The dwelling assigned, ascribed to Israel is the House of the Book. Heine’s phrase is exactly right: das aufgeschriebene Vaterland. The ‘land of his fathers’, the patrimoine, is the script. In its doomed immanence, in its attempt to immobilize the text in a substantive, architectural space, the Davidic and Solomonic Temple may have been an erratum, a misreading of the transcendent mobility of the text.

Steiner’s essay is characteristically staggering, from the explication of Hegel at the beginning through the rhapsody on Kafka in the middle to the passage of literally prophetic (and no doubt controversial) anti-Zionism at the conclusion, yet at its heart is one sentence I would like to spray-paint on a wall: “The sole citizenship of the cleric is that of a critical humanism.” In a similarly ecumenical spirit, Bloom concludes:

Yet if there is something undying in the Jewish concern with text, perhaps we might see a saving elitist remnant that in some odd Messianic sense will make “Jews” of all—Gentile or Jewish—who study intensively.

The period from 1945 to 2001 in America may have been an anomaly in human history. This was the period that birthed the English major as we know it, and that led gentile English majors to say things like, “I think I may well be a Jew” (Sylvia Plath), and, “I am the last Jewish intellectual” (Edward Said).

Does critical humanism finally annul itself by abolishing literacy per se as criticism’s final prey? Confronted by her students’ inability to parse hypotactic sentences, Harvard professor Amanda Claybaugh claims, sounding for all the world like Steve Sailer, “Their capacities are different.” “And what right has anybody to impose anything upon those with different capacities?” the critical humanists finally ask themselves, turning their methods on their methods, the snake swallowing its tail.

Meanwhile, out in the wilds, some of us are doing what we can, however inadequate, to hold it together—last week I was synthesizing Catholicism with Nietzsche in the persons of Wilde and Joyce.3 It occurs to me now that the synthesis of Catholicism with Nietzsche in the persons of Wilde and Joyce amounts to what Steiner, at least, more or less meant by “Jewish”— which would neither have surprised nor bothered Joyce.4

I recently heard a right-winger say on a podcast that novels written by people who pursued graduate education couldn’t possibly be worth reading. I guess we’re supposed to work on a fishing boat or something rather than learning how to write books by reading the best books written. This fetishization of physical labor for physical labor’s sake (similar to orthodox Marxism) is symptomatic of American conservatism’s slide back into suburban troglodytism after the brief opening of the Trump years, an opening misunderstood by everyone, including Trump himself. For my part, I will say frankly and in the demotic to those conservatives: if you think I’m going to waste on a completely worthless 9-to-5 job my forebears’ leap from “the idiocy of rural life” to the opportunity afforded by this chaotic country, you can go fuck yourself. (And if conservatives persist in this psychotic hatred of art, this “get a real job, you faggot” attitude toward their sons with artistic inclinations—an attitude that wholly defined their movement in my youth and was only slightly alleviated by their recently choosing the Wildean aesthete Trump to be their figurehead—they will not only be culturally-revolutioned by the left, but they will deserve to be.) I know I have gotten above what believers in innate “capacities” would regard as my proper station—my family going from the most literal illiteracy to a Ph.D. in literature in three generations—but, as the poet said, “My life is not an apology, but a life.” I am here to read books, I am here to write books, without apology; I won’t be doing much of anything else. This, come to think of it, is also what I would like to tell the associate professor who dismissed me from my adjunct position.

Shattuck proposes the oral recitation of literature in the classroom as a cure for literary studies’ ills, since—here he forthrightly defies the general drift of structuralism, poststructualism, and media theory from Saussure to Barthes and McLuhan—it will make literature as meaning and as affect radiantly present to students. I think this is charming, if a bit fanciful, but it may help Harvard undergraduates find their way through the labyrinth of Hawthorne’s subordinate clauses. What does it matter that even the most elite students can no longer read periodic sentences, sentences that suspend their sense in a balanced structure of subordination, almost 100 years after Hemingway killed such sentences off as a vehicle for serious literature? In the worst-case scenario, it means our future elite will be unable to think the complexly ordered thoughts such sentences model. But then, I can’t read Latin or Greek, and neither (I believe) could Hemingway, so we’ve probably all been—again, excuse the demotic—screwed for a long time.

O my prophetic soul: just after I wrote that, Justin Murphy had Catholic professor Paul Fortunato—a member of Opus Dei, no less—on his podcast to sing Wilde’s praises. Fortunato pairs Wilde with Tolkien, at Joyce’s expense, as equivalent popular evangelists. This is an error, as I once tried to explain on Tumblr: Tolkien may be more popular, but Joyce is far more influential. In the arts, influence is better than popularity.

No one complained last week—I really thought someone would—so I’ll have to do it myself: “Why does it matter to you, Pistelli, to align your literary and philosophical commitments with the faith of your fathers when you don’t practice that faith—and, for that matter, neither does your father?” Call it a metapolitical wager. If this is true, I’d hate to end up on the wrong side of it.

How does this invocation of Christ square with the rumination on Judaism above? In his essay, Steiner argues that Christian supersessionism would have been legitimate had Christianity not been politically incorporated—had Catholicism not aligned itself with empire and Protestantism with nation. Had Christianity contented itself to remain in exile, Steiner claims, it would in effect also have remained Jewish. Poetically defining Christ as the absolute antonym of Caesar gets at a similar thought, I believe. This is to equate both Judaism and Christianity with antinomianism, which is of course insane, but leave it to the poets.

Bravo.

These essays have been brilliant of late. You’re obviously on a sort of roll, which I presume is related to the novelistic writing, so consider me pledged!