A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

My novel Major Arcana slouches toward Substack to be born. I am a chapter away from having the first half finished and polished. The serial begins here next Monday, the 20th of March, the vernal equinox. A preface will appear before then to advertise its plot, promote its aesthetic, and contextualize its politics. The novel will be for paid subscribers only, so please pledge your subscription today.

For today, a wholly uncontroversial piece about why literature cannot really co-exist with the psychological or psychotherapeutic mentality—less according to me than according to Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Kafka, Woolf, Plath, Williams, Pynchon, Kane, Ishiguro, McCarthy, and more.

“Never Again Psychology!”: Why Writers Would Rather [X] Than Go to Therapy

I’ve sat for a while on an essay gathering together observations I’ve made over the years on major modern writers’ objections to the discipline of psychology in all its avatars, from its status as a theoretical science to its clinical practices as both talk therapy and pharmacology.1 When writing about this topic, like others touching on identity politics, one is supposed to plaster one’s discourse with disclaimers (“I am not an expert,” “I am not judging anyone”) that are necessarily belied by one’s choosing to essay on the topic at all. If I didn’t prefer my own insight to “expertise,” if I didn’t intend at least some measure of “you must change your life,” then why on earth would I bother?

I despise this false humility. I find its sentimentalism more coercive, because more insidious, than any pronouncement ex cathedra could ever be, not to mention its bizarre hint, whether true or false, that the writer entirely lacks conviction and therefore should have remained silent. I prefer the brutal frankness admitted by authors of the older generation, like Didion in “Why I Write”—

In many ways, writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind. It’s an aggressive, even a hostile act.

—or Vidal in his essay on Mailer—

What matters finally is not the world’s judgment of oneself but one’s own judgment of the world. Any writer who lacks this final arrogance will not survive very long in America.

The writer should admit the inherent arrogance and presumption of the act—and then trust the equally inherent finitude of language to open a space of irony in which the reader may answer rather than simply acquiesce. I am as an essayist tempted toward categorical statement, and I rarely resist this temptation; my ambivalences, hesitancies, and contradictions tend to be marked not in the sentence nor in any given essay but in the chamber of resonance and discordance that would be formed by reading several of my essays in sequence.2

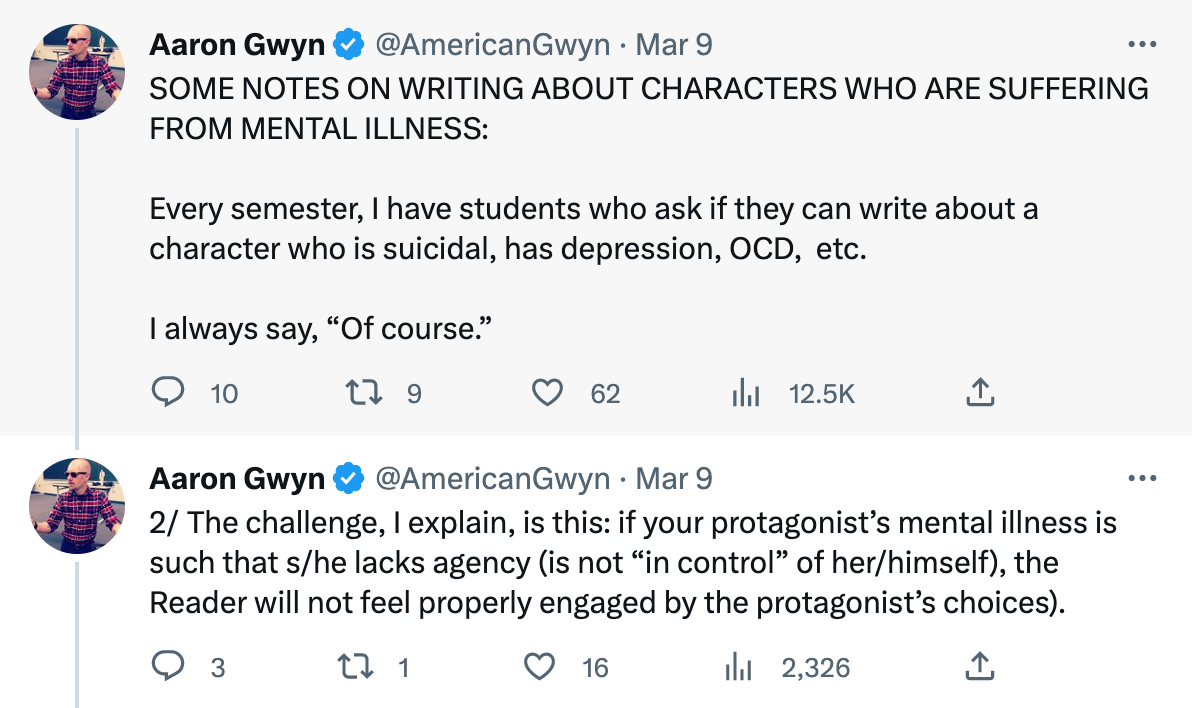

A few clashing Twitter threads and then a recent LitHub essay makes me revisit the essay against psychology this week; most of it, with revisions, is posted below. First, the increasingly and enviably ubiquitous writer Aaron Gwyn shares in a thread his advice to students about writing characters with mental illness.

This is admirably well-intentioned, and it’s probably the best possible advice for writers in an institutional setting, but all the same it reveals the contradictions in the way we think about the very category of “mental illness.”3 If one retains one’s full complement of agency, then in what sense other than the sheerly hypochondriacal can one be said to be ill? Yet if illness revokes one’s agency entirely, then narrative literature becomes the Zolaesque record of organic degeneration. The latter is a plausible aesthetic choice—it worked for Zola—but I note that Gwyn’s beloved Faulkner and McCarthy usually only flirt with this possibility before finally swerving (yes, even McCarthy, at least most of the time) into a Christian humanism sacralizing moral choice in the teeth of all exterior determinations. I conceive my own characters without any reference whatsoever to clinical categories, which tend to age about as well as styles of dress.

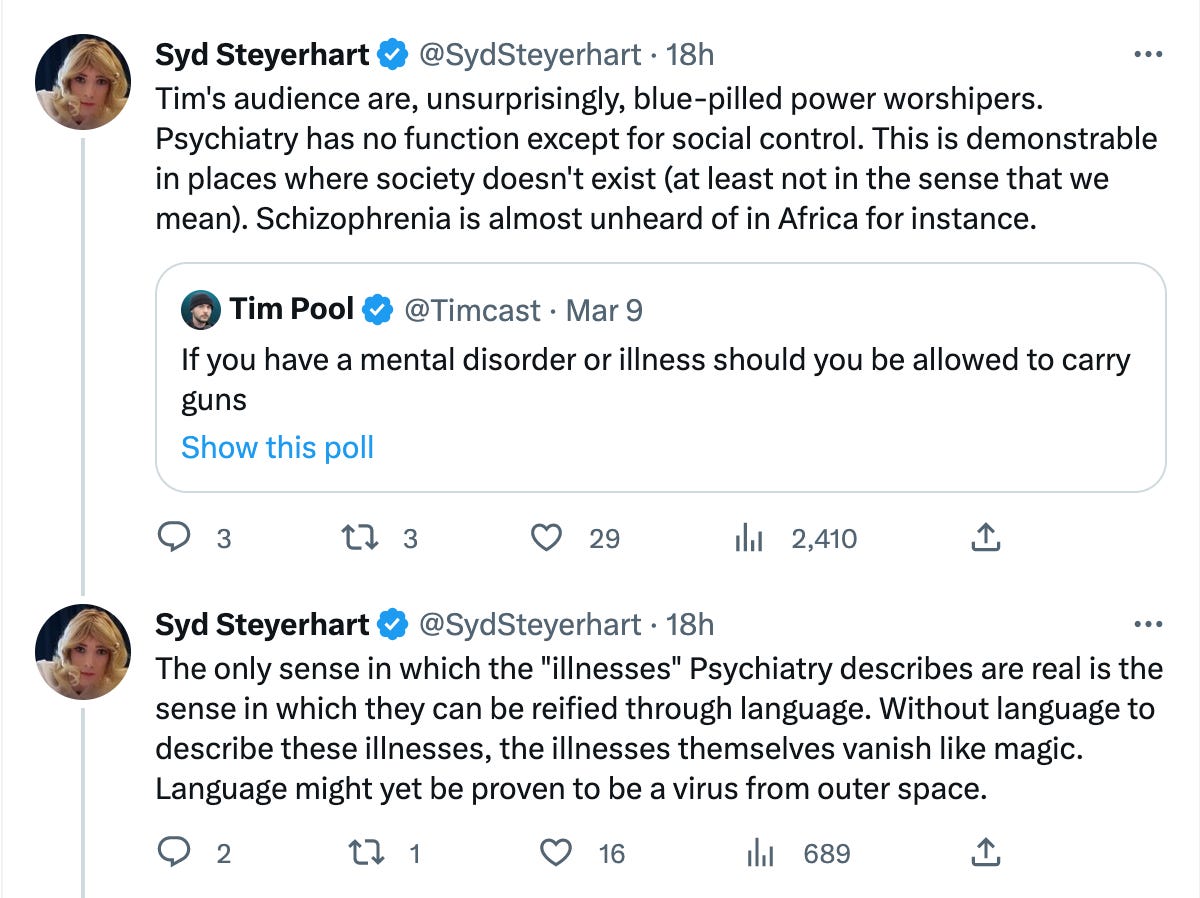

On the other side of the ledger, the Twitter personality or persona Syd Steyerhart—a nihilistic and vaguely neoreactionary trans woman literarily devoted to Thomas Ligotti and the aforementioned Cormac McCarthy—makes the case against psychology at its most absolute, in a beguiling conflation of Tumblr-2012 talking points with the Burroughsian anarcho-fascism those talking points were perhaps always destined to wed:

I draw my title—“Never Again Psychology!”—from Kafka: it appears, albeit crossed out, in his Zürau Aphorisms. Its relevance to his fiction is almost self-explanatory. His stories are fables without morals, parables without counsel, allegories with no key. They are aggadah without halakah, as Walter Benjamin put it in terms of Jewish tradition: the legends without the rabbinic body of legitimating, legislating, and explanatory comment. Why does the hunger artist starve or Josephine sing or the creature obsess over his burrow? Why do the authorities try Josef K.? Why does K. remain in the village? If we understood their childhoods, their “traumas,” even their brain chemistry, would we have an answer that mattered?

In an essay on the merit of psychotherapy for writers, Veronica Esposito suggests its chief merit is in freeing us from having to be Kafka:

To put it into literary terms, it’s a little like I switched the genre of my life—from say the claustrophobic modernism of a Franz Kafka to the truth-seeking comedy of a Lorrie Moore.

Going from Franz Kafka to Lorrie Moore is a pretty stunning change, and I think it shows the depth of what therapy can achieve. At its deepest, therapy seeks to make foundational change in who a person is.

Esposito implicitly suggests we should wish Kafka to have been otherwise—not just better treated or better behaved, but fundamentally different. (What a thing to imply about the 20th century’s single most distinctive literary sensibility.) And while it’s fun to make “men would rather do [X] than go to therapy” jokes, the final sentence of the quoted passage, in all seriousness, horrifies me. I would do almost anything to stay out of the clutches of a person or institution aspiring to that, an almost classically 20th-century totalitarian impulse to sweep away the populace and build in its place the “New Man.” It is the opposite of how I understand (have come to understand through literature) what it is I am here to be and to do in the world.

Born with certain capacities and shaped in early life by certain forces beyond my control, I made even before I was really old enough consciously to make certain commitments. None of this is fair from our delimited vantage, but it is the way it is. To renege on the commitments of my nature would be to commit that dishonor to which, proverbially, death is preferable. This nature may be enlarged, adumbrated, variously interpreted, and immeasurably improved—deliberately put to its highest possible use. In this sense, I believe consciousness to be infinite: there is no limit to the John Pistelli I can be. I think this is what Nietzsche meant by “becoming who you are.” But to be otherwise than John Pistelli? No: character is fate. Foundational change, besides being undesirable, is probably also impossible. Whatever “therapy” Esposito means to indicate, even Freud the enlightened conservative and Jung the mystic traditionalist would probably disclaim this totalizing desire.4

Kafka, anyway, was hardly alone among major modern writers in mistrusting the psychological sciences and their clinical excrescence. Dostoevsky hated psychology because, like sociology, it strips us of our Christian free will as moral agents. We will not be able to plead before the Throne of Judgment that we committed evil acts because mommy didn’t love us enough. As Gary Saul Morson comments:

“They call me a psychologist; this is not true,” Dostoevsky wrote. “I am merely a realist in the higher sense, that is, I portray all the depths of the human soul.” Dostoevsky denied being a psychologist because he, unlike practitioners of this science, acknowledged that people are truly agents, who make real choices for which they can properly be held responsible. No matter how thoroughly one describes the psychological or sociological forces that act on a person, there is always something left over—some “surplus of humanness,” as the philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin paraphrased Dostoevsky’s idea. We cherish that surplus, “the man in man” as Dostoevsky called it, and will defend it at all costs.

Even those of us who don’t share Dostoevsky’s faith may heed his warning that psychology will serve modern power by reducing us to stimulus-and-response machines of whose treatment as disposable objects there may be no rational moral objection.

It is a short step from Dostoevsky’s critique in the 1870s to Thomas Pynchon’s in the 1970s: the villain in Gravity’s Rainbow is Pavlov, for obvious Dostoevskean reasons. We shouldn’t forget Dr. Hilarius either, the Nazi psychoanalyst in The Crying of Lot 49, whose methods, which include both talk therapy and the prescription of hallucinogenic drugs, threaten human freedom no less than Pavlov’s more obviously totalitarian conditioning. Hilarius devoted himself to psychotherapy’s melioristic delusions, he confesses, to atone for his use of the science to torture prisoners in Buchenwald:

“And part of me must have really wanted to believe—like a child hearing, in perfect safety, a tale of horror—that the unconscious would be like any other room, once the light was let in. That the dark shapes would resolve only into toy horses and Biedermeyer furniture. That therapy could tame it after all, bring it into society with no fear of its someday reverting. I wanted to believe, despite everything my life had been. Can you imagine?”

Nabokov, who hated Dostoevsky and who educated Pynchon, more simply viewed the psychologist as a threat to the writer’s own imaginative freedom:

Mr. Nabokov, would you tell us why it is that you detest Dr. Freud?

I think he’s crude, I think he’s medieval, and I don’t want an elderly gentleman from Vienna with an umbrella inflicting his dreams upon me. I don’t have the dreams that he discusses in his books. I don't see umbrellas in my dreams. Or balloons.

I think that the creative artist is an exile in his study, in his bedroom, in the circle of his lamplight. He’s quite alone there; he’s the lone wolf. As soon as he’s together with somebody else he shares his secret, he shares his mystery, he shares his God with somebody else.

If this is too solipsistic, however, Nabokov’s fiction presents a more pointed social and political critique: in Lolita, for example, where psychology’s post-Freudian focus on child sexuality mirrors Humbert’s own predation, hence the novel’s infamous pun: “as the psychotherapist, as well as the rapist, will tell you…” The Nabokovian satire here wittingly or unwittingly recalls Freud’s abandonment of the so-called “seduction hypothesis”—i.e., his transition from finding the etiology of neurosis in real early-life abuse to blaming childhood fantasy instead.

Virginia Woolf, one in a long line of female writers ill-served by psychology from Charlotte Perkins Gilman to Sarah Kane, and herself the victim of the child sexual abuse Freud would not hold responsible for mental illness, fulminated in an essay against “Freudian Fiction” (which reduces its characters, she complains, to “cases”):

A patient who has never heard a canary sing without falling down in a fit can now walk through an avenue of cages without a twinge of emotion since he has faced the fact that his mother kissed him in the cradle. The triumphs of science are beautifully positive.

Like her beloved Dostoevsky before her, Woolf, who hallucinated the birds singing in Greek, would rather tolerate real evil and real suffering, even her own, than have them medicated away into an anodyne and false happiness in what her younger contemporary Aldous Huxley satirized as Brave New World.

In Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, Septimus Warren Smith, the novel’s co-protagonist and visionary artist, his mind shattered by the Great War, jumps out a window to his death rather than find himself subject to the psychology of Dr. Bradshaw. As Woolf’s narrator explains in a passage of angry and almost Dickensian exposition out of place in the otherwise involuted modernist novel, Bradshaw stands for the virtues of “Proportion” and “Conversion,” values the British Empire inflicts at gunpoint on the world at large:

But Proportion has a sister, less smiling, more formidable, a Goddess even now engaged—in the heat and sands of India, the mud and swamp of Africa, the purlieus of London, wherever in short the climate or the devil tempts men to fall from the true belief which is her own—is even now engaged in dashing down shrines, smashing idols, and setting up in their place her own stern countenance. Conversion is her name and she feasts on the wills of the weakly, loving to impress, to impose, adoring her own features stamped on the face of the populace.

When the novel’s other and titular protagonist meets Bradshaw, she understands why Smith killed himself rather than succumbing to the physician.

Sylvia Plath equated the male antagonists of her two most famous poems—her father in “Daddy” and the psychologist “Herr Doktor” in “Lady Lazarus”—to the Nazis and herself as daughter-patient therefore to the Nazis’ Jewish victims. As in Tennessee Williams’s life and work—both his sister’s lobotomy and Blanche’s climactic straitjacketing in A Streetcar Named Desire—psychology here represents male domination at its stiffest and straightest, a rigid phallocracy determined to expunge from human experience whatever affronts its drive toward norm and regulation, toward Proportion and Conversion.

The experimental dramatist Sarah Kane, who, like Woolf and Plath, killed herself after unsuccessful treatment, wrote in her final play, 4.48 Psychosis, that psychiatry in its late 20th century pharmacological phase, by cauterizing the wellspring of her despair, would also dry up the source of her art:

Please. Don’t switch off my mind by attempting to straighten me out. Listen and understand, and when you feel contempt don’t express it, at least not verbally, at least not to me. […] There’s not a drug on earth can make life meaningful. […] I won’t be able to think. I won’t be able to work.

Psychology can’t help Kane because its rationality can do nothing to alleviate the even-more-rational rationality of despair, as if talking about omnipresent suffering and unavoidable death or using drugs to numb one’s awareness of them could do anything fundamental to ameliorate their threat. All these treatments will do is annul the artistic expression of despair—one of the only acts that makes despair bearable.

Cormac McCarthy’s most recent novel, Stella Maris, also dramatizes a woman who eventually commits suicide in colloquy with a psychiatrist, and the result is the same as in Kane’s life and work. The religious title of McCarthy’s novel and the Biblical allusions in Kane’s play suggest that only a leap of faith, not an endless and basically narcissistic circular conversation about one’s feelings or experiences, can save the individual from the horror of existence.5

The 20th-century psychologists who failed Woolf, Plath, and Kane, and who lobotomized Rose Williams, were all male. In our own century, however, psychology has gone from preying on female patients to being female professionals’ own domain, as the broad middle classes are increasingly subject to majority-female regulatory bodies and therefore to specifically feminine modes of domination, the type Wollstonecraft deplored as the weapons of the weak in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: no longer the forthrightly brutal jackboot and straitjacket, but spurious and manipulative appeals to compassion and consensus, behind which, of course, lurk the same old threats of what Woolf called Proportion and Conversion.

Not coincidentally, the signal literary dystopia of the 21st century is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go: the story of an organ farm for clones disguised as a progressive boarding school run by enlightened liberal women and devoted to the therapeutic development of the doomed pupils’ ability to express themselves. Ishiguro so effectively conceals a disturbing satire inside a page-turner that his vast readership of enlightened liberal women seem not to recognize themselves and their cultural ethos as the satire’s target; but Ishiguro, who cites Dostoevsky as one of his major influences, indicts a society awash in a mawkish therapeutic jargon that legitimizes rather than ameliorating oppression: as long as we all “feel seen,” the powerful may as well strip us for parts.

Whether the steely patriarchal imperialism of the early 20th century arraigned by Woolf or the sentimental matriarchal managerialism of the early 21st identified by Ishiguro, psychology, according to our major writers, is just tyranny misspelled.

Why, then, did Kafka cross out his aphorism? The very act of canceling an exclamatory demand—as if one had momentarily lost one’s head and then thought better of one’s outburst—is itself almost comically neurotic. Michael Cisco comments:

So why cancel this one? The only way is the way forward, which would entail taking psychology to its end, causing it to evolve into something new, at which point the old psychology would drop away. Or one could create an alternative, but it would still have to involve the issues and problems of psychology in order to function as an alternative. Simply banishing psychology is not only impossible, as what’s done can’t be wished away, but it would also mean an attempt to go backwards, which is always impossible in Kafka.

In other words, we probably aren’t, at least for now and at least in the aggregate, headed back to the church or the synagogue or the shaman, so secular replacements for their function, including the function of pastoral care, will likely prove durable. What would “taking psychology to its end” look like?

Speaking for myself, it will look like an accomplished and depthless (in both senses) work of literature. While therapy pragmatically would never work on me because I would very simply never disclose to a single stranger in a professional setting the final secrets of my being, I will tell an indeterminate and potentially unlimited number of strangers these secrets in the form of my fiction. As Gertrude Stein said, I write for myself and for strangers.

I confess, however, that if the institutional aspiration of therapy really is the “foundational alteration” of the individual, then I feel for it something more than a personal wariness—something closer to a political antipathy, of the kind that makes me wonder if such a “profession” shouldn’t be publicly regarded in the light of a predatory cultus or a criminal gang.

I originally intended it as my

essay before deciding it was best not to foul someone else’s nest with a piece so contentious. Instead, in “Extraordinary Machine,” I wrote about writers and technology.I probably learned how to do this from Susan Sontag, who probably learned it from the God of the Hebrew Bible: nothing to command deference, or at least attention, like a litany of clashing commandments and inexplicable reversals. See my praise for Sontag’s majesty in my negative review of Sontag: Her Life and Work, where biographer Benjamin Moser, overtly defending pop psychology as a literary hermeneutic, posthumously and extra-clinically diagnoses an author he seems to find despicable with a Cluster B personality disorder—a typical use of psychological diagnosis at once to conceal and to evade moral judgment.

The archaic-romantic “madness” is a preferable term to anything more recent or expert-derived, by the way, because of the deep-fathomed connotations still clinging to it—the dignity even in the pit of degradation, for instance, of Lear. “Mental illness,” by contrast, reeks of the odorless clinic, still more of the laboratory, where the psycho-scientists julienne mouse brains and fail to replicate their experiments, because they have not grasped that consciousness is immeasurable, wily, and finally unable to be directly observed, let alone explained.

Leaving aside their clinical legatees and legacies, such as they exist, are Freud and Jung themselves enemies to literature or examples of it? Freud could be as alarmingly reductive a literary critic as he was charmingly complex an essayist. For example, he reduces the most complex of texts as he reduces the most baffling of dreams to mere wish-fulfillment in his essay “Creative Writers and Day-Dreaming”:

We are perfectly aware that very many imaginative writings are far removed from the model of the naive day-dream; and yet I cannot suppress the suspicion that even the most extreme deviations from that model could be linked with it through an uninterrupted series of transitional cases.

Freud nevertheless survives in our time almost solely as a writer: a modernist canvasser of the inner life and remaker of ancient myths in new guises, no less than Yeats, Joyce, or Eliot, and hailed by Harold Bloom, not unpersuasively, as the 20th-century Montaigne.

In “On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry,” Jung upbraids his mentor Freud for critical reductionism. Jung remarks particularly on Freud’s confusion of symptoms with symbols; he mocks Freud’s critical method for flattening profound images of truth like the Platonic allegory of the cave into shallow evidence that “even a mind like Plato’s was still struck on a primitive level of infantile sexuality.” Jung finds the source of art—or at least of great art—not in the artist’s personal history and sexual pathology but rather in the artist’s openness to whatever primordial images of the collective unconscious are most required to heal the illness of the artist’s age:

That is the secret of great art, and of its effect upon us. The creative process, so far as we are able to follow it at all, consists in the unconscious activation of an archetypal image, and in elaborating and shaping this image into the finished work. By giving it shape, the artist translates it into the language of the present, and so makes it possible for us to find our way back to the deepest springs of life. Therein lies the social significance of art: it is constantly at work educating the spirit of the age, conjuring up the forms in which the age is most lacking. The unsatisfied yearning of the artist reaches back to the primordial image in the unconscious which is best fitted to compensate the inadequacy and one-sidedness of the present.

While we might hesitate at the essential conservatism of this vision—it still binds the artist to the past, in this case the past of humanity at large—and at the Star-Wars-portending conviction that archetypes deserve to overwhelm thematic complexity in a way quite foreign to actual ancient literature—where in the Iliad or in the Book of Job do we find the supposedly time-honored battle between good and evil?—Jung still restores to the artist the world-making power confiscated by psychological reductionism.

In sum, we are probably justified in agreeing with Bloom that, as a prose-artist in the traditions of wisdom- and essay-writing, Freud far surpasses Jung; but we might equally accede to Deleuze’s judgment that Jung is more profound a psychologist than Freud, since Jung tips us like bagged goldfish out of the suffocatingly cloistered tropes of the family romance and into the world-ocean of the archetypes. See YouTuber Angie Speaks’s provocative recent video, “Carl Jung Solves the Culture War.”

The play’s the thing. Psychoanalysis in its Freudian variant is famously little more than an elaborate annotation of Hamlet’s tortured soliloquies, but none of this self-expression, none of this rooting around in the infant’s frustrated sexual desires, none of these “words, words, words,” helps the princeling one bit, much as it may entertain us. There is no cure in talking. At the end of the play, Hamlet stops trying to talk his way to action and understands instead that one must act thoughtlessly and, as it were, on faith:

[W]e defy augury: there’s a special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ’tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come: the readiness is all: since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

The Biblical allusions here reinforce Kane’s and McCarthy’s own religious references. Perhaps only a god can save us.