A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week, Ross Barkan of Political Currents published a conversation with me about my new novel, Major Arcana. We discussed the novel’s inspiration, the state of contemporary fiction and publishing, and some of the topics raised in the novel, such as the influence of comics on culture, magic and occultism, gender identity, and suicide. Immodesty compels me to quote Ross’s generous introduction at length:

Major Arcana arrived to me with no hype, no fanfare. I was a regular reader of Pistelli’s Substack but knew nothing of his prior work, the novels he had already published. I opened the novel, which clocked in at more than 700 pages, and began to read.

What I found, perhaps, is the elusive great American novel for the twenty-first century. Pistelli is sweeping and satiric, tender and deliciously strange; a fine melding of Don DeLillo, Alan Moore, and the great-noticers of the human condition who came barreling through the nineteenth century. Major Arcana is a tremendous and serious book. It will linger with me for a long time and my belief is that it will eventually find many new readers. It is better than almost any fiction being produced today.

If you would like to read this “great American novel”—remember, I didn’t say it: Ross Barkan said it!—it’s available in print here and in various electronic formats available to paid subscribers of this Substack. I will send a free pdf to anyone who pledges to write a review in a public forum; just contact me at johnppistelli@gmail.com or DM me on here. I will mail (or have Amazon ship) a print copy to any editor or writer who wants to review it in a prominent publication.

I also released this week for paid subscribers my latest episode of The Invisible College, “In an Age of Surfaces,” an account of the life and work of Oscar Wilde with a reading of The Importance of Being Earnest as that life and that work’s fraught and tragic apogee. Next Friday: Joseph Conrad and The Secret Agent, a novel that, with its hapless political radicals and false flag terrorist attacks and Russian imperialist aggression, hasn’t aged a day since 1907.

For today, two short pieces: one about book reviewing in the light of this week’s literary querelle, including my ambivalent call for review copies, and one about academic freedom in the light of a recent controversy about professorial advocacy for terrorism, including my rueful memoir of once having collaborated with the advocate. Please enjoy!

Sharpening the Hatchet: On Book Reviewing

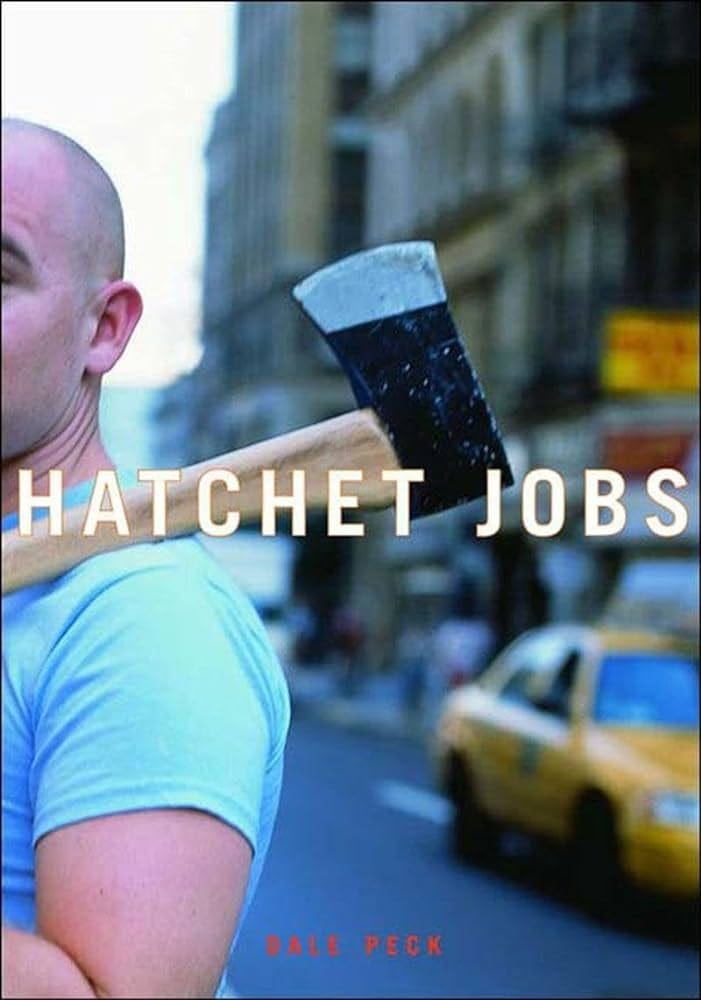

The literary controversy of the week was about a bad book review, a nicely done hatchet job in Bookforum by Ann Manov. As I said elsewhere, I came of literary age in the heyday of James Wood, Dale Peck, Christopher Hitchens, Lee Siegel, and others, a time when even Gore Vidal remained active, and so I love a brutally bad review if it’s well-written and informed. As Susan Sontag said of Dale Peck’s extreme way with the hatchet, “The forest needs him.”1 On the other hand, when it comes to writers reviewing writers, I also think of the proverb: “When the axe came into the forest, the trees said, ‘The handle is one of us.’”

The whole affair made me reflect on my years maintaining a literary blog consisting of “book reviews” originally published to Goodreads. Mostly these were essays on the classics that I came eventually to think of as introductions best suited to undergraduates. (I came to think of them this way because I came to realize that undergraduates were the people reading them. My own students would quote my essays at me, sometimes because I was very neutral and non-partisan in the classroom, as teachers ought to be, whereas I was more cutting and polemical in the reviews.) That wasn’t my intention when I set out almost 10 years ago, though; my intention was to be part of the “literary conversation,” which meant reviewing contemporary work. I wanted to be part of the literary conversation on the theory that this would attract people to my novels. Despite the twists and turns my intellectual and literary life has taken, I wanted to be a novelist, not a critic. I found, however, that “the literary conversation” was pretty impenetrable for a blog written by someone outside the metropole, and that my good and bad reviews made next to no impact.

I think I acquitted myself well in the circumstances of the last decade’s political extremism and instability. When works celebrated for their political “urgency” or whatever were actually compromised by politics I found half-baked or dishonest, I didn’t hesitate to say so, even at the risk of giving offense, as in my review of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer or my review of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen. On the other hand, a novel with bien-pensant politics can be a truly great novel all the same, as I showed in my review of Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive. If a contemporary novel deserved to be noticed as a likely classic, an all-time success, I was glad to join in the noticing, for which see my review of Anna Burns’s Milkman. I even plucked something both small-press and bien-pensant out of almost total obscurity, because I chanced upon it in a library, and because it was amazing—see my review of Jayinee Basu’s The City of Folding Faces—even though its author seems to have given up writing for Marxist psychiatry. If a hatchet job had to be written, I wrote one, especially when it came to nonfiction I feared might have a bad influence: see my review of Benjamin Moser’s moralizing Sontag biography and my review of Benjamin Bratton’s brazenly totalitarian pandemic manifesto.2

If these reviews made any dent in critical consciousness, though, I didn’t see any evidence of it. It was a pretty popular blog, but no one would send me review copies, except publicists who emailed me on behalf of clients who in their retirement had written and self-published their memoirs and the like (I rarely read memoirs). Who knows, maybe I was even blacklisted for saying The Sympathizer was no Invisible Man! You’d think people would want serious critical attention rather than just a fawning positive review amounting to a press release—I could write three or four articles myself on the ideological and aesthetic flaws in Major Arcana!—but perhaps that’s not the way the world works. I decided that all this reviewing was a thankless task, and that I would give reviewing up (unless paid to do it by a prominent publication, as when I reviewed Joseph Epstein—a hatchet job!—for RealClearBooks last year) in favor of this weekly newsletter and podcasting about the classics.

I was persuaded, however, by the aforementioned Ross Barkan’s argument that we in this independent literary space ought to be reviewing books, especially small-press and independently published books. Accordingly, when someone on Substack contacted me and asked if I’d like a review copy of his forthcoming novel, I said yes. (It helped that I was already familiar with his writing from podcast appearances and occasional essays, including, ironically, this one.) I was also happy to be offered a review copy of the Invisible Dragon reissue last year and had great fun reviewing it.

I hesitate to open the floodgates here, because I don’t want to be deluged by endless publicists promoting books I obviously don’t want to read, My Year at Horse Camp or whatever. But if you have a book you think I might appreciate—familiarity with my tastes and interests would help; I am mostly interested in serious fiction and literary criticism-scholarship-biography, though poetry, comics, and miscellaneous nonfiction of a philosophical, political, art-historical, or theoretical nature are also welcome—and you’re willing to send me a print copy, then you can feel free to contact me at the email address in my bio or DM me on here.

I never liked the logrolling and back-slapping attitude of the “literary community,” though, so don’t expect a supine posture and bland, murmured praise. If I can write three or four negative reviews of my own novel, and I can, what do you think I can do to yours? With all those caveats in place, you may take your chances.

(And to any editors out there, let me state again my availability to write reviews for your publication.)

Long Bloody Sunday: On Freedom of Speech and “The Revolution”

I’ve told parts of this story before elsewhere, but, for the benefit of new readers, let me tell it again, inspired in part by current events and in part by my just having reread Conrad’s The Secret Agent, a novel I don’t think I understood when I first read it over 20 years ago.

Circa 2005, I was part of a radical-left group blog called Long Sunday. Naming the blog was a difficult matter. Someone wanted to call it Por Ahora, because Hugo Chávez once said that his initial socialist coup had only failed “por ahora” (i.e., “for now”). Another member vetoed this on the grounds that it sounded too much like Tora Bora, a then-notorious theater of the Afghan War. Someone else asked, striking a rare note of good sense, “Do we really want to name our blog after something the President of Venezuela said?”

I forget how we arrived at Long Sunday. I wasn’t in favor; a friend and I agreed that it sounded like an emo band (e.g., Taking Back Sunday). The name’s source was a somewhat ambiguous line from German playwright Georg Büchner’s radical manifesto The Hessian Courier: “The life of the rich is like a long Sunday.” For our subtitle we also borrowed Büchner’s call to arms: “Peace to the cottages! War on the palaces!” The idea was that we occupied a historical interregnum, but that Monday—The Revolution—would come eventually, with its war upon the palaces.3

It was all very stupid; I shudder to think of what I wrote there when I was 23 and 24. Some of the personnel of this group blog still have a place in contemporary letters or scholarship, however. Nina Power, now of Compact magazine, for example, was a member, and the whole thing orbited the online circle around Mark Fisher, though I in my youthful ardor belonged to the humanist (which in this context meant Stalinist or Third-Worldist) faction opposed to Fisher’s theory’d-up Deleuzean-Landian concept of capital as autonomous alien intelligence.

Another member of our little digital revolutionary cenacle was Jodi Dean. I don’t remember much about what she wrote, except for a blog entry about traveling to the Soviet Union with a student group in the 1980s and feeling uplifted at the sight of the hammer and sickle. “Oh God,” I remember thinking with a bit of second-hand embarrassment even then—being both a somewhat ironical and a somewhat pacifistic person, I was never going to make much of a revolutionary, not to mention that, living up to a bit of an immigrant’s-child stereotype in this respect, I maintain allegiance to only one flag.

Anyway, Dr. Dean, Professor of Political Science at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, has made the news this week. For the Verso blog—how far we’ve come from Long Sunday!—she published an essay arguing in effect that Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7 was an event of the kind around which a universal revolutionary subject might crystallize, thereby re-establishing “Palestine” as the name of the exploited and excluded class of our time whose resistant to the total world order of empire can potentially set us all free.4

The paragliders who flew into Israel on October 7 continue the revolutionary association of liberation and flight. Although imperialist and Zionist forces try to condense the action into a singular figure of Hamas terrorism, insisting against all evidence that with the extermination of Hamas Palestinian resistance will disappear, the will to fight for Palestinian freedom precedes and exceeds it. Hamas wasn’t the subject of the October 7 action; it was an agent hoping that the subject would emerge as an effect of its action, the latest instantiation of the Palestinian revolution.

Here is a typical instance of the intellectual left shopping in the global boutique of our information economy for a revolutionary subject: someone, anyone, to bear the Christ-like burden of suffering in their own person for the ransom of all mankind from our “age of absolute sinfulness.”

There is no persuasion, only conversion. If you are of the faith, then this theology makes sense; if you aren’t, and I’m not, then it doesn’t. Human beings in historical time can’t play this role in a drama of metaphysical emancipation, and when they try, disaster inevitably ensues. Whatever access to eternity we have, we find in art or in nature or in love or in prayer. We don’t find it, and we shouldn’t even look for it, in the conflict of peoples and states. Jesus Christ, the original revolutionary subject, was wise to remind us of the essential boundary between God and Caesar. He also suggested that not repaying Caesar’s violence in kind was a holy act. I interpret this less as a strict injunction to pacifism than as a reminder that taking up the sword on behalf of politics, even if it becomes necessary, will never be God’s work.5

All of the above is to say that I reject Dean’s gospel of violence. I will go further and say that the prevalence of such views in academia and other elite cultural institutions—I don’t mean pro-Palestinian attitudes; I mean theologies of The Revolution—has done damage to intellectual and artistic life in this country.

One doesn’t apply one’s principles à la carte, however. Part of my rejection of The Revolution—the idea of a time when dissension, no longer being necessary, will be at an end—involves my commitment to liberal principles like freedom of speech and academic freedom. I follow Mill in advocating a robust conflict of ideas precisely because this contest functions as a sublimation of what might otherwise be political violence. Didn’t Dean begin as a Habermas scholar? Does not Habermas somewhere speak of “the unforced force of the better argument”? Dean’s argument should be heard—and then it should be explicated and refuted, as I’ve done above. It should not be suppressed. If suppressed, it is likely to appear more persuasive, persuasive with the almost erotic radiance of the forbidden and taboo, than it actually is.

I am sorry to hear that Dr. Dean has apparently been suspended from teaching on the basis of her essay, then, and for whatever it may be worth I condemn this action on the part of her academic superiors. My heart never lifted at the sight of a totalitarian flag—and how better to spend a long Sunday than in an endless and free conversation?

Peck’s bad-boy stance got him in trouble more recently for what can only be described as his negative review of Pete Buttigieg’s very person. Peck’s credo, quoted from his collection Hatchet Jobs at the link, which collection I read in my last year of college, has influenced my own critical practice:

Lots of great books are built around flawed or at any rate contestable social theories, like Remembrance of Things Past, or Mishima’s novels, and let’s not forget our very own William Faulkner. In fact—and this may merely be a product of my own education in deconstruction and identity politics—I take it as a given that the social theories which inform works of fiction should be contested by the reader, precisely because they are made up; ultimately—and this may be just a product of my education in a more classical formalism—a novel’s true merit (or lack thereof) rests on aesthetic considerations.

As for the rest, Hitchens and Vidal died, and Wood mellowed out after publishing a couple of novels and marrying a novelist. On the latter topic, Ann Manov has already given critical fortune her own artistic hostages, as in the short story “The Last Days of Bohemia,” whose brand of realism is not totally to my present taste but which I thought nevertheless exhibited a superb, eloquent intelligence of social and psychological observation.

Moser told Dan Oppenheimer he didn’t read his bad reviews when he appeared on Eminent Americans. Since both Blake Smith and I were on Eminent Americans before him, I have to believe it!

21st-century leftist organs have a weakness for this kind of vague promise. There’s n+1, of course, with its hint that something will be added to the present, even if we’re not sure what. More recently, we have The Drift, a title no doubt meant to convey the drift or gist of an argument, but also suggesting aimless flow, spinning like a leaf on history’s tide. Give Jacobin points for forthrightness, I suppose.

As I showed here, no less an advocate for the Palestinian cause than Edward Said himself also held what he allowed was a “basically metaphorical” view of actual Palestinians, who function for these theorists as abstract allegorical figures in the revolutionary drama they are trying to script. In the same post, I also review my own published anti-Zionist rhetoric of the mid 2000s in light of current events, partly recanting and partly stating my distrust of the current Israeli government’s brutal conduct of the war. In the ideological conflict over Israel right here on Substack between Curtis Yarvin’s supposedly hard-headed realpolitik of warfare and Sam Kriss’s supposedly soft-headed condemnation of nihilistic violence on all sides, I am at one with Kriss.

Like my novel’s hero-villain Simon Magnus, when I use the word “God” I intend it as “a placeholder for the intelligence of the structure.”

Do we need a “magazine” on substack, a la the Mars Review of Books, to legitimize the criticism so that advance copies are obtainable? The American Review of Books? The Substack Review of Books? The Hatchet? If there were an easy way to directly divvy up the revenues amongst authors I’d help pull it together. Zero desire to be a paymaster, but a model where the revenues were split up at the source would be cool.

I quite enjoyed Manov's takedown of Oyler (whose work I've never read, beyond opening and then immediately closing her novel), which seemed well-researched and excitingly spiteful (although she was apparently quite thin-skinned about my own making fun of her last year...), but the Peck comparison is alarming (the girls, including Rothfeld, all seem to want to compare themselves back to the mid-century New York intellectuals, but the last-generational comparison seems more correct)... I've been reading him a bit as I work through a pile of OUT magazines from the 90s-10s (he was a book and movie reviewer for them), and his work is really dreadful--lazy, petulant, pointless, and not aimed in the service of anything in particular, neither a vision of good literature nor of what would be 'good for the gays' (ofc much bad reviewing has that axe-grinding quality, but I do expect a thinking person's reaction to some work of literature to include taking seriously some notion--hopefully sophisticated, complex, supple, and alive--of what literature should be and do, and of a 'for whom?' literature and criticism ought to be)... and what I've read of his own fiction (Martin and John) is just awful, pseudo-experimental crap. He's still remembered for some zingers, but otherwise a literary life that just as well might not have been lived.

That said, unfortunately, takedowns get the most attention... I think you're the only writer to have noticed my positive appreciations of Howard, Riding, etc (of course then again you're also the subject of one!)--nobody knows you when you're nice!