Dave Hickey, The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty and Other Matters

beauty enfranchises desire

This classic 1993 book by art critic Dave Hickey has just been released by Art Issues Press in a 30th-anniversary edition: a (dare I say?) beautiful hardcover, appropriately saurian green with letters in firebreath-red. (For the newcomer, let me gloss the title: the “dragon” is beauty, which Hickey pronounced “the issue of the nineties,” “invisible” due to its neglect in the art world after modernism.) Editor Gary Kornblau—who, in disclosure, sent me a review copy—has added several articles from the whole breadth of Hickey’s career to The Invisible Dragon’s original four essays and has contributed an afterword that is equal parts memoir and critique. For this occasion, , , , and I have agreed to do a Substack colloquium on the book. Dan has written a biography of Hickey—I haven’t read it yet, alas, but Blake reviewed it here—and an introduction to our symposium, while Blake posted his piece, “Dave Hickey, That Queer,” yesterday. The following essay picks up some of the motifs in the latter to run with them in my own direction. (Unlike Dan and Blake, I am encountering Hickey for the first time with this reissue.) My further reflections will probably follow once everyone has contributed. Please enjoy!

Dragon, Lady: Capitalism and/as Woman in Dave Hickey’s Art Criticism

Everyone is female, and everyone… Just kidding. Sort of. I’ll come back to the point shortly; for now, since Blake Smith’s first entry in our symposium and Gary Kornblau’s afterword between them have covered the territory of Dave Hickey’s queerness or “queerness” or queerness, I want to start with a different dimension of Hickey’s argument: his elegy for capitalism and his curse on the bureaucracy that replaced it.

Blake has already quoted Hickey’s account of modern art’s origin in the casual talk of two Renaissance men about why they preferred Raphael to Michelangelo. In “Prom Night in Flatland,” he extends this praise for the jostle of unsystematic exchange to a jocularly cynical account of how Picasso learned to flatter the changing tastes of his buyers—how this, and not some Hegelian journey through mental space to the logical terminus of painting-qua-form, led him to the modernist breakthrough of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. “Les Demoiselles, ce sont moi,” he might have said, the ones selling sex, the other selling art, all taking pleasure in the unregulated and unpredictable circulation of commodities, including the self as commodity:

For nearly seventy years, throughout the adolescence of what we call high modernism, professors, curators, and academicians could only wring their hands and weep at the spectacle of an exploding culture in the sway of painters, dealers, critics, shopkeepers, second sons, Russian epicures, Spanish parvenus, and American expatriates. Jews abounded, as did homosexuals, bisexuals, Bolsheviks, and women in sensible shoes. Vulgar people in manufacture and trade who knew naught but hard money and real estate bought sticky Impressionist landscapes and swooning Pre-Raphaelite bimbos from guys with monocles, who, in their spare time, were shipping the treasures of European civilization across the Atlantic to railroad barons. And most disturbingly, for those who felt they ought to be in control—or that someone should be—beauties proliferated, each finding an audience, each bearing its own little rhetorical load of psycho-political permission.

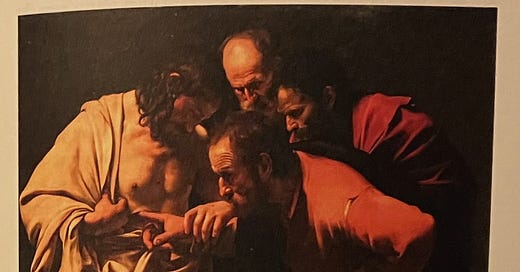

“Permission”—what Hickey elsewhere, and with a greater democratic thrust, calls “enfranchisement”—is a key word. In an American pragmatic (or Pragmatic) spirit, beauty is Hickey’s synonym for the efficacy of the picture: on one level, what draws you to it, even makes you want to buy it, but, on perhaps a higher level, what in the picture makes you recognize your own desires, and not only as your own but also as picturable and therefore shared, publicly thinkable, though they may turn out to be desires you didn’t even know you had until you saw the picture. It’s like Martin Amis’s doleful remark about how you should avoid getting into pornography because you never know what you might discover you enjoy—except here expanded into an ideal of individual and collective freedom to enlarge our sensibilities, and without being hassled by church and state. In the bad old church-and-state days, a painter like Caravaggio had to put his eye for the proto-decadent beauties of sex and death in the service of the Counter-Reformation. But modern markets allow a Picasso (or a Mapplethorpe, about whom more in a moment) to put beauty for its own sake, which is to say for the sake of the desires it enfranchises in the viewer, on public display.

To this classically emancipatory vision of social and political modernity—consider only Hickey’s roll call of the emergently enfranchised in the passage above, of whom Jews, homosexuals, and women are the paradigmatic figures—the early years of artistic modernism bore chaotic, cubistic witness. Then, after World War II, someone seized control—in this case, what Hickey labels the publicly-funded “therapeutic institution,” the state-museum-academia network of experts whose imprimatur the artwork now had to receive to be promoted or even shown to the public. Under this new church’s mandate to educate the laity on what our taste ought to be, the gaudy “pre-Raphaelite dragon” of beauty unleashed by the modern market was banished, and in its place arose an ideal of cold late-modernist formalism whose blankness only enfranchised, before an increasingly indifferent public, the institution’s own ongoing ministry.

For the flavor of Hickey’s libertarian incredulity in the face of the art world’s fashionable but belated anti-capitalism, consider this Philip Rothian tirade in escalatingly rhetorical questions, from the essay, “Enter the Dragon”:

If you broached the issue of beauty in the American art world of 1988, you could not incite a conversation about rhetoric—or efficacy—or pleasure—or politics—or even Bellini. You would instead ignite a conversation about the marketplace. That, at the time, was the “signified” of beauty. If I said, “Beauty,” they said, “The corruption of the market,” and I would say, “The corruption of the market?!” After thirty years of frenetic empowerment, during which the venues for contemporary art in the United Stated evolved from a tiny network of private galleries in New York into this vast, transcontinental sprawl of publicly funded, postmodern iceboxes? During which the ranks of “art professionals” swelled from a handful of dilettantes on the East Side of Manhattan into this massive civil service of PhDs and MFAs administering a monolithic system of interlocking patronage (which, in its constituents, resembles nothing so much as that of France in the early nineteenth century)? During which powerful corporate, governmental, cultural, and academic constituencies vied ruthlessly for power and tax-free dollars, each with its own self-perpetuating agenda and none with any vested interest in the subversive potential of visual pleasure? Under these cultural conditions, artists across this nation are obsessing about the market?

This brings us to the essay “Nothing Like the Son,” Hickey’s appreciation of Robert Mapplethorpe’s BDSM photography in the controversial X Portfolio, not to mention Hickey’s greater appreciation for the conservative lawmakers who wanted to ban Mapplethorpe than for the curators and academics who defended him. The defenders abstracted away Mapplethorpe’s content—his chronicle of fist-fucking and cock-fingering and such—to praise the formal achievement of his stark photography, which indeed owed something, as a spread in this book demonstrates, to Caravaggian chiaroscuro. Or worse, they abstracted the pictures into vague principles of free expression or the benefit of art as such, no matter what art, to society. The attackers, by contrast, grasped the photos’ efficacious beauty rather than their inert form or banal status as “art” when they understood such images as legitimating for and maybe even inciting in the viewer novel styles of desire. At least the censor takes the work seriously, Hickey suggests. The curator, by contrast, will curate anything with the same chin-stroking blandeur. Such a principled defense can call itself a defense of freedom, but in robbing the picture of its “right,” so to speak, to alter its audience, or of the audience’s right to be altered by the picture, it is a regression to the church-and-state days of art’s prostration despite its progressive rhetoric.

Though Hickey uses a gay male artist’s battles in the Moral-Majority-era to make this point, however, I want to turn now to his identification of beauty and its enfranchisements with the feminine, again in “Prom Night in Flatland,” subtitled, “On the Gender of Works of Art.” Defending the use of pictorial depth against the “flatland” of the modernist canvas, and mourning as well that all the properties once belonging to figurative painting (people, landscapes, interest, rhetoric) have now moved with some simplification in the process to fields like dance and performance art, Hickey surmises that a fear of the feminine motivates the partisans of the late modernism that then flourished in the therapeutic institution:

It should be clear by now that the structure of my argument is threefold. First, I am suggesting that over the last four-hundred-odd years, the “work of art,” and particularly the painting, has undergone a number of perceptual gender shifts. The demotic of Vasari’s time invested work with attributes traditionally characterized as “feminine”: beauty, harmony, generosity. Modern critical language validates works on the basis of their “masculine” characteristics: strength, singularity, autonomy. Second, I am suggesting that the dynamics of these gender shifts presuppose that the gender of the artist and the beholder are not shifting, which of course they are. Third, I am suggesting that, since the rhetoric of flatness applies primarily to painting, the “death of painting” in the late 1960s and the rise of three-dimensional, photographic, and time-based genres marked nothing more than a growing discomfort with the mythologies of “modern painting,” which in fact have less to do with the paintings themselves than with the critical language used to defend them. These conditions would seem to invite a more radical rethinking of the gender dynamics inherent in our perception of contemporary and historical art than any of us probably have time for.

This observation is why I keep using the term “late modernism” to name Hickey’s foe, even though Hickey himself calls the institution “postmodern.” To my mind, postmodernism happens (among other moments) when the shift in the gender (and race and sexuality) of the presumed artist and beholder becomes recognized, as indicated by the fact that Hickey was writing in and around the period not only of Mapplethorpe but also of Basquiat, Sherman, Kruger, Haring, etc. His polemical target, by contrast, is the modernist teleology, stereotypically white and European, that leads to the presumed death of painting, entombed in a thousand post-Malevich blank canvases.

Hickey mentions, for example, Michael Fried, an art theorist whose most famous essay, “Art and Objecthood” (1967), derides everything in art that might be associated with what he calls the “theatrical” and upholds instead the ideal of a bounded and enclosed form making no histrionic appeal to anyone—precisely the opposite, then, of Hickey’s argument for beauty-as-enfranchisement, for Picasso’s whores advertising their wares beneath the proscenium arch of the frame. Giving away the gender-and-sexuality subtext that Hickey only guessed at, a line from a letter of Fried’s later surfaced, as recorded in his Wikipedia entry:

I keep toying with the idea, crazy as it sounds, of having a section in this sculpture-theater essay on how corrupt sensibility is par excellence faggot sensibility.

And here we rejoin the ongoing discussion of Hickey’s queerness or “queerness” or queerness. I take “faggot” here, considering the theatrical connotation it had for Fried, to be not quite synonymous with “gay” in the same way that “queer” is not. It can even, in its adjacency to the effeminate, or to the actor’s lability of gender, stand opposed to “gay,” with its more exclusive implication. Gore Vidal’s usage, as quoted by Leo Robson, is illustrative:

Vidal told Amis that he had been reading D. H. Lawrence: “Every page I think, Jesus, what a fag. Jesus, what a faggot this guy sounds.”

Lawrence, the apostle of phallic masculinity, the phallocrat of modernism taken down by a million second-wave feminist critics—a faggot? Granted, there’s that naked male-on-male tussle in the drawing room from Women in Love, but Vidal doesn’t mention content. He mentions sound. And how does Lawrence sound? Earnest, impassioned, rhapsodic, sermonic, prophetic—like someone addressing you, like someone crying out to you, like someone trying to convince you, like someone trying to sell you a vision, like someone maybe even trying to enfranchise you with a broader sensation of desire than the one the narrow world has given you already. Lawrence was not a painter—well, he was, just not one remembered for his paintings—but primarily a novelist. The novel arguably began enfranchising its working- and middle-class readers about a century before painting did, if we accept Hickey’s historiography.

Hickey likes to quote Foucault. The novel’s preeminent Foucauldian historiographer, Nancy Armstrong, famously argued in her Desire and Domestic Fiction (1987), published only a few year before The Invisible Dragon, that the modern individual emerged first in novels, novels like Pamela and Moll Flanders and Emma and Jane Eyre, and that this individual, a creature of deep longings suited to the emergent market economy, was, as those novel titles indicate, first and foremost a woman. Even her male authors, even her male readers, wrote and read as women. When capitalism reigned, everyone was female—and everyone loved it. To the extent that Hickey mounts a similar case for the history of painting, this is how we may tie the knot wrapping beauty, capitalism, femininity, and queerness in one package.

A 30th-anniversary edition, though, invites us to wonder how the argument has aged. The bureaucratic and therapeutic institution still stands three decades later, but rhetoric like Michael Fried’s, and the type of artistic practice it defended, no longer rules. In fact, the therapy the therapeutic institution now provides is likelier to be defended by its exponents in terms of femininity and especially queerness—if not literally in terms of therapy—rather than any muscular modernist defense of arduous abstraction; at this point, the latter might almost be refreshing. I have analyzed at length elsewhere—in my review of Benjamin Moser’s Sontag: Her Life and Work—how a certain feminine style of domination commandeered bureaucratic high culture in the 21st century, very much at the expense of female modernist intellectuals like Sontag, as evidenced by Moser’s own mawkish disapproval of Sontag’s imperiously self-enfranchised style.

Would Hickey, then, have us celebrate the less regulated space of “online,” with its autocurated personae theatricalizing themselves in every available way on every available platform from TikTok to OnlyFans to, well, Substack? I suspect, no matter how sexy the photos or witty the memes or cunning the entrepreneurialism, he might mourn the loss of the labor and intelligence exhibited in the painting (or the palpable presence of the performer, as in Hickey’s tributes to Dolly Parton and Richard Pryor): for this, too, was a constituent of beauty.

Linking tHickey’s faggotry to sound, a la Lawrence’s, is the nub of the argument so far in this fascinating (to me, anyway) Substack colloquium.