A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

While my novel-writing sabbatical from longform criticism continues, I did write a quick summary post of books read in January, quite the omnium gatherum (now that I don’t feel obligated to write 3000 or 4000 expert-sounding words on everything I read, I feel freer to strike out hopefully in odd directions):

My weekly newsletters this year have resembled the blogs of yesteryear, pursuing a definite set of questions and a determined cast of cultural characters through their facets and permutations. Today’s weekly newsletter addresses (not for the first time in the history of this Substack: see here and here) the suddenly omnipresent “gnostic question.” Conservatives and classical liberals like James Lindsay blame “gnosticism” for what is otherwise variously called leftism or wokism.

Meanwhile, people who are more culturally literate, even those who pay no obvious fealty to leftism or wokism, mock the trend. In my continuing manifestation of an appearance on my new favorite podcast, Art of Darkness, I cite its co-host, the novelist Brad Kelly.

As a belletrist, I can’t claim to be a scholar of the matter. I haven’t even read Hans Jonas yet. When I read a few gnostic gospels in college for the legendary Rebecca Denova’s two-semester sequence on the origins of Christianity, I found most of them to be (at least for philistine contemporary audiences) a quasi-unreadable hash of neoplatonic jargon. The exception, of course, is the luminous Gospel of Thomas: “Jesus said, ‘Become passers-by.’” Harold Bloom in The Western Canon (about whom and which more in a moment) compares this in both tone and counsel to Walt Whitman. Bloom saw America for both good and ill as gnosticism’s nation, so it came to him as no surprise to find the national bard sounding like a gnostic gospel.

Still, even as a non-expert, I’ve long been interested in modern and contemporary manifestations of this ancient energy, in both elite and popular culture. To contribute to the discourse, I offer three pieces below. First, to clarify terms and concepts—just what is gnosticism?—I provide a repost of my 2017 review of Elaine Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels, the book that more than any other popularized gnosticism in the late 20th century; my essay also contains perhaps useful allusions to other authors on the subject. Second is a note on gnosis in relation both to radical politics and to the literary canon, with help from Harold Bloom. Finally, a postscript revisiting one pop gnostic from last week’s post, Grant Morrison.

“Like Artists”: Elaine Pagels’s The Gnostic Gospels

In this 1979 classic of popular nonfiction, religious scholar Elaine Pagels explains to a broad audience the theological significance of the trove of early Christian writings discovered at Nag Hammadi in 1945. She also places these documents in their social and political context, largely to explain why the diverse body of thought labeled “gnostic” was so decisively defeated by the ideas and institutions of what would become Christian orthodoxy. Finally, Pagels, while unsurprised by gnosticism’s defeat, suggests the perennial appeal—if only to artists, mystics, and other anti-social types—of the gnostic vision, with its emphasis on individual spiritual experience as against all hierarchies and establishments.

What is gnosticism? While Pagels is at pains to emphasize the diversity of the Nag Hammadi writings (the “gnostic gospels” of her title), some generalizations can be made. Gnosticism tends to posit the creator God of the Hebrew Bible as a mere demiurge, who fashioned this botched reality we inhabit out of malice or stupidity; the true God lies well beyond nature, and is only evidenced by the sparks of divinity lodged in the souls of human beings, like gems scattered amid offal. Because this world is not merely fallen but evil or illusory, then human hierarchies and institutions are religiously irrelevant, and the believer comes to God not by following someone else’s rules but by attaining private knowledge (gnosis) of the God within.

Given gnosticism’s dismissal of nature and the body, gnostics deemphasize the figure of Christ as incarnate God, a God who is also flesh and who died a real death. For gnosticism, Christ is rather a kind of alien emissary modeling the ascended human rather than the descended deity: “Jesus was not a human being at all; instead, he was a spiritual being who adapted himself to human perception,” Pagels explains.

Finally, with hierarchies made irrelevant by the distance of the true God, gnostics understate the gender distinction so important to Christian orthodoxy and instead give a greater place to female spirituality and indeed female divinity. Gnostics have no need of codes and canons:

[L]ike artists, they express their own insight—their own gnosis—by creating new myths, poems, rituals, “dialogues” with Christ, revelations, and accounts of their visions.

The body of thought that would win out over gnosticism stressed, by contrast, an ordered hierarchy:

As God reigns in Heaven as master, lord, commander, judge, and king, so on earth he delegates his rule to members of the church hierarchy, who serve as generals who command an army of subordinates; kings who rules over “the people”; judges who preside in God’s place.

As Christianity expanded, its institutions could not sustain the kind of spiritual anarchy gnosticism portended if it was to organize a mass constituency:

Seeking to unify the diverse churches scattered throughout the world into a single network, the bishops eliminated qualitative criteria for church membership. Evaluating each candidate on the basis of spiritual maturity, insight, or personal holiness, as the gnostics did, would require a far more complex administration.

Pagels concludes that “the religious perspectives and methods of gnosticism did not lend themselves to mass religion.”

The above summary hints at who Pagels seems to be asking us to sympathize with: the plucky anarcho-feminist artists against the stodgy authoritarian bishops. This is a more serious book than that, though. For example, Pagels stresses the importance to believers of Christ’s incarnation, especially in the context of Christian persecution: how gravely moving it is to worship a God who was willing to suffer just as you suffer. The gnostic’s quasi-Platonic hologram Christ is, in a sense, much less interesting or original—just another theophany who doesn’t really bleed or weep as we do.

Moreover, gnosticism is a private religion, with each member his or her own church, whereas, Pagels explains, “[r]ejecting such religious elitism, orthodox leaders attempted instead to construct a universal church.” Pagels understands that in religion (as in politics) there is a necessary tension between the individual and the collective, insight and iteration, agency and structure, anarchy and community. She shows the gnostic traces in orthodox thought from the Gospel of John to the dissents of the church fathers—because even the orthodox sometimes feel the need to make a separate peace with our alien cosmos—just as she carefully notes the less appealing qualities of gnosticism’s more chaotic theology.

But gnosticism is appealing for all that. Pagels observes that, while it was extirpated by orthodoxy, it survived throughout the Christian era from medieval heresies (e.g., the Cathars) to Protestant mysticism. She several times mentions psychoanalysis as a modern manifestation of gnosticism: “For gnostics, exploring the psyche became explicitly what it is for many people today implicitly—a religious quest.” Not to mention the Romantic poets and post-Christian philosophers and proto-Existentialist novelists who have been drawn to a sublime of spiritual insight beyond matter and humanity:

William Blake, noting such different portraits of Jesus in the New Testament, sided with the one the gnostics preferred against “the vision of Christ that all men see” […] Nietzsche, who detested what he knew of Christianity, nevertheless wrote: “There was only one Christian, and he died on the cross.” Dostoevsky, in The Brothers Karamazov, attributes to Ivan a vision of the Christ rejected by the church, the Christ who “desired man’s free love, that he should follow Thee freely,” choosing the truth of one’s own conscience over material well-being, social approval, and religious certainty.

Pagels does not mention, because, I assume, it was much less visible in 1979, gnosticism’s massive influence in late-20th-century popular culture, an influence that is probably at least partially attributable to her own book; see a semi-whimsical old Tumblr post of mine for details, and see Victoria Nelson for a more responsible treatment.

Most disappointingly to me, she also does not mention the political interpretation of gnosticism: Eric Voeglin, for instance, believed that modern political movements like Marxism and fascism, with their “ruthless critique of everything existing” (per Marx) and their consequent desire to re-organize all human life according to otherworldly ideas of justice, derive essentially from gnostic thought—a controversial idea updated for the post-Cold-War period and its perhaps now collapsing neoconservative-neoliberal consensus by such thinkers as John Gray and Peter Y. Paik.

Pagels’s focus on gnostic anarchy and individualism may well be an antidote to such attempts to materialize the alien God through the bloody rites of mass politics. Likewise, Herman Melville imagined, in his remarkable short lyric “Fragments of a Lost Gnostic Poem of the Twelfth Century,” that gnosticism enjoins withdrawal from all activity, an ineradicable spiritual impulse despite its worse-than-uselessness to the organization of humanity:

Found a family, build a state,

The pledged event is still the same:

Matter in end will never abate

His ancient brutal claim.Indolence is heaven’s ally here,

And energy the child of hell:

The Good Man pouring from his pitcher clear

But brims the poisoned well.

“Heresy of Heresies”: Heresiarch in Bloom

As quoted above, James Lindsay surmises that Marxism derives from “Hermetic Gnosticism.” While it’s easy to reply to this in the jaded, knowing tones of the now-dated Chapo Trap House ironist—“Jimmy Concepts is having a normal one,” and other such embarrassing sub-Simpsonsisms—as if to say that such speculations are obviously paranoid John Bircher nonsense, I would argue instead that it is perhaps not paranoid enough.

That Marxism derives from Hermetic Gnosticism is a commonplace by now, I would think. I remember reading “Hegel as Hermetic Thinker” online almost 20 years ago. Or consider the following passage, written by an old Marxist professor of mine in a 2014 peer-reviewed book published by Stanford University Press, no less, which argues for the 18th-century Neapolitan scholar Giambattista Vico, the first philosopher to attempt a comprehensive, holistic theory of human society and historical change, as the fount of the Marxist tradition:

If there is any interest in Vico today in either one of those two circles, it is mainly because of [Edward] Said. But a lineage is always greater than a single life, and that principle applies to Vico as well, since by “Vichian” I am referring not to him alone but to a philological, antinomian, globalist outlook that he developed in a particular way in response to the scientific Enlightenment on the periphery of European intellectual life. He wrote and thought within a line of descent beginning well before him—before even Plato, his philosophical parent, to whom he pays homage frequently. Vico absorbed the lessons of Neoplatonism, as well—especially its reliance on Arabic learning, Egyptian sources, and Alexandrian hermeneutics. Vico’s minoritarian intellectual position was, as I have said, modeled on Varro in Roman antiquity but also on medieval scholarly legacies, already implicitly secular, to which, as Martin Bernal has observed, Vico was heir. These in turn championed the legendary Egyptian founder of writing, Hermes Trismegistos (a.k.a. “Thoth,” the etymological root of Greek theos, or “god”), as the founder of nonbiblical or “gentile” philosophy and culture.

Through Vico and Hegel, Marxism derives from Hermeticism and gnosticism, the former named for the possibly fabulous Hermes Trismegistus. More precisely, Marxism inverts Hermeticism and gnosticism, infusing them with an Enlightenment materialism to make the mage’s will and the adept’s gnosis a latent potential of humanity at large to master matter with matter, sans the detour through the astral plane, and thus accomplish the liberation of the gnostic’s alienated divine spark right here on earth, transfiguring the prison into a garden.

This metamorphosis of magic into Marxism is implied and anticipated by Vico’s historical narrative of the shift from poetry—sensual apprehension of the truth, expressed sublimely in metaphor and archetype, akin to the magician’s symbols and correspondences—to philosophy and science—the abstract apprehension of truth, expressed dryly in that logical language of arbitrary but self-consistently systematic signifiers favored by scholars. But this is not an objection; it’s just an observation.

Objecting to gnosticism only makes sense, anyway, from within the frames of normative Judaism, Christianity, or Islam—if you’re sure you can rid even these of heresy, though when, in Catholic school, they would line us up on the communists’ beloved first of May to crown a statue of the Blessed Mother with flowers in the garden of the rectory, I’m not sure anything I would call “normative” was involved.1

To clarify this question, I turn to the most ill-understood book in our long and exhausting culture war: Harold Bloom’s 1994 manifesto and vade mecum, The Western Canon. Following not Marx but the Joyce of Finnegans Wake, Bloom models his book on Vico’s historiography.2 He traces western culture through its Vichian phases from theocracy to aristocracy to democracy—and then to our present chaos, what Vico calls the turbulent ricorso that begins the cycle again.

But Bloom also joins his argument for the Western Canon to his prior controversial case that gnosticism not only survives in modernity but dominates American culture, so much so that gnosticism is (to cite another of his titles) The American Religion. In The Western Canon, Bloom claims that the high liberal literary tradition stemming from Dante—the earliest author Bloom discusses—is itself gnostic. The very tradition that conservatives and classical liberals like Lindsay wish to preserve from the gnostic left is, in other words, always-already infested with the heresy.

Readers tend to remember Bloom as aiming this argument at the academic left, and he very much did. He arraigned the left’s materialism and identity politics for reducing both writers and readers to economic and political categories and thereby dispelling imaginative literature’s imagination-expanding sublimity, its capacity to augment rather than to reduce the self. But this exact same argument cuts against the right as much as the left. The right’s desire to find piety and morality in literature won’t survive an encounter with the most expansive writers any more than will an attempt to find social justice in them.

For Bloom, the proper use of literature is a private one, in line with the gnostic vision: the author’s divine spark whispering to the reader’s. His essay on Dante provides the most scandalous example. Bloom claims that the poet heretically exalts Beatrice as his own private gnosis:3

Dante’s progeny among the writers are his true canonizers, and they are not always an overtly devout medley: Petrarch, Boccaccio, Chaucer, Shelley, Rossetti, Yeats, Joyce, Pound, Eliot, Borges, Stevens, Beckett. About all that dozen possesses in common is Dante, though he becomes twelve different Dantes in his poetic afterlife.

[…]

Vico rather splendidly overstated his case when averred of Dante that “had he been ignorant of Latin and Scholastic philosophy, he would been even greater as a poet, and perhaps the Tuscan tongue would have served to make Homer's equal.” Nevertheless, Vico’s judgment is refreshing when one wanders in the dark wood of the theological allegorists, where the salient characteristic of the Comedy becomes Dante's supposedly Augustinian conversion from poetry to belief, a belief that subsumes and subordinates the imagination. Neither Augustine nor Aquinas saw poetry as anything except childish play, to be set aside with other childish things. What would they have made of the Comedy’s Beatrice? Curtius shrewdly observes that Dante's conversion is to Beatrice, not to Augustine, and Beatrice sends Virgil to Dante to be his guide, rather than sending Augustine.

[…]

Though dead, white, male, and European, he is the most alive of all the personalities on the page, contrasting in this with his only superior, Shakespeare, whose personality always evades us, even in the sonnets. Shakespeare is everyone and no one; Dante is Dante. Presence in language is no illusion, all Parisian dogma to the contrary. Dante has stamped himself upon every line in the Comedy. His major character is Dante the Pilgrim, and after that Beatrice, no longer the girl of the New Life, but a crucial figure in the celestial hierarchy. What is missing in Dante is the ascension of Beatrice; one can wonder why, in his daring, he did not also illuminate the mystery of her election. Perhaps it was because all of the precedents he had were not only heretical, but belonged to the heresy of heresies, Gnosticism. From Simon Magus onward, heresiarchs have elevated their closest female followers to the heavenly hierarchies…

Bloom’s charge against his proto-“woke” leftist enemies, upon whom he memorably hung the Nietzschean label “the school of resentment,” was that they, in their reductive materialism, are the true conservatives. They attempt to dispel with their mean-spirited euhemerism the spiritual force of individualism churning beneath ancient religious orthodoxies and set free in the greatest modern writers. Literature, not Marxism, is the only true revolution, says Bloom—is the revolution Marxism pretends to be. The suffocating cultural discipline favored by the left, in contrast, with its rigid rules and orthodoxies, its multiplying constraints upon the individual, isn’t gnostic enough—isn’t woke enough.4

The problem with Marxism on this view is neither its mystic source nor its vision of universal emancipation, then, but its corruption of these into a soulless materialism that leads by logic—precisely by logic—to a permanent immurement in what Philip K. Dick called “the Black Iron Prison.” Materialism, we might say, is not only stupid but the paradigm of stupidity, as in the memento the wretched Brecht kept on his writing desk: a toy donkey with a sign around its neck that read, “Even I must understand it.”

Polemicists like Lindsay, who still repose their faith in a Newtonian or Darwinian science, the implications even of modern physics having passed them by, can’t begin to understand any of this because they have no feel for the aesthetic. They are literally being driven as crazy as the narrator of a Lovecraft story by studying the humanities for the first time in middle age, without the protective cultivation of affective response an earlier exposure would have given them. For there is a problem with gnosis, as Bloom himself acknowledges:

If we read the Western Canon in order to form our social, political, or personal moral values, I firmly believe we will become monsters of selfishness and exploitation.

I happen not to believe this—here, Bloom should have heeded his beloved Shelley in “A Defence of Poetry”—but it does follow from the gnostic perspective. So self-absorbed is the gnostic, even if the “self” concerned is a shard of God lodged 1000 feet below even the psyche or consciousness, that the gnostic forgets what the orthodox and, yes, even the poets sometimes remind us. Beatrice wasn’t just a private gnosis, but a living, breathing woman. I quote Whitman: “a kelson of the creation is love.”

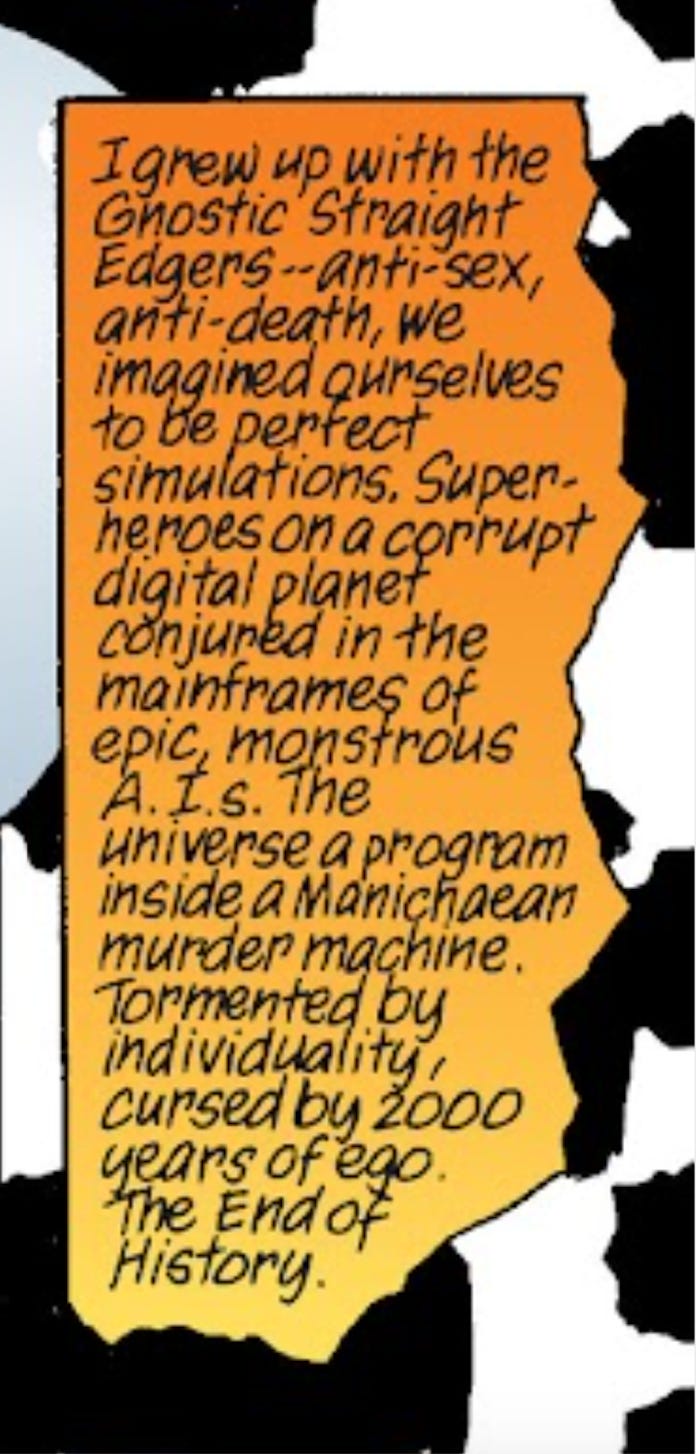

Pop-Culture Postscriptum: Grant Morrison’s “Germ Free Generation”

Last week I discussed the occult influence of comic-book writer Grant Morrison’s pop gnosticism on contemporary culture. In case you doubted me, Morrison was trending all day 48 hours later with the announcement that the new DC superhero movies would be based on some of the chaos magician’s comic books. I dimly remembered—and then had to find on Internet Archive—that Geoff Klock, who published an excellent book in 2002 applying Harold Bloom’s poetics to superhero comics, had written an article in the mid 2000s on Bloomian gnosticism and Morrison’s New X-Men series: “X-Men, Emerson, Gnosticism.”

In New X-Men: Germ Free Generation, Grant Morrison introduces John Sublime, a self-help Guru who preaches to his followers, the U-Men, of a Third Species (not unlike gender theory’s idea of the Third Sex) in which super-powered mutant organs (like X-ray eyes) are transplanted into human bodies: homo sapiens and homo superior (mutants), claims John Sublime, will both be replaced by his third species, homo perfectus. (The U-Men reveal their connection to Gnosticism in their choice to wear a kind of scuba gear: they will not breathe the air of the “fallen world” until their mutant grafts make them perfect.) New X-Men: Riot at Xavier’s connects Post-Humanism with the process of education itself; only in the X-Men are the Post-Humans supe[r]heroes and visionary students and teachers. Quentin Quire, leader of a school protest that gets out of hand, eventually experiences a “secondary mutation” in which he is completely dissolved into light, a scene that suggests Gnostic transcendence, but also current theories identifying the Post-Human with the dissolution of the ego. The Stepford Cuckoos, students at the school, are identical telepathic girls who refer to themselves as the “five-in-one,” suggesting theories that locate the Post-Human in larger social co-operative units. There is a mutant drug “Kick,” for those who look toward chemicals for transcendence from the human.

What is really surprising about these recent X-Men books is the way this lush, Post-Human pluralism is allowed to be completely eclipsed by the Phoenix, a creature described in Ultimate X-Men as “an Ultra-dimensional entity that wants access to this reality so it can annihilate [this world] like it annihilated a billion worlds before us. It talks…in Latin and…wants to decreate and unravel everything God has ever made.” In Morrison’s New X-Men, the Phoenix is simply described as burning away everything that isn’t necessary. The Phoenix Force is seen as the highest power—the extreme endpoint of evolution understood in these books. In terms of Gnosticism it might be conceived of as the Gnostic God (a rare figure in pop culture); the language of the leader of the Hellfire Club who attempts to harness it through Jean Grey attests to as much: “We want to replace your God with our own chap, Charles. After twenty billion years in this many-angled prison.” The phrase Hans Jonas uses in the subtitle for his seminal book on Gnosticism, “The Alien God,” is appropriate here. The Phoenix is alien in every sense (including extra-terrestrial): it is eternal, outside space and time, and has no regard for individuals or any part of the created universe. This is the central problem: the Phoenix is a negative endpoint—the dark idea that will eventually be produced by evolution’s violent progress from Human to Post-Human and beyond—not a progressive Post-Human utopia, but something completely alien and inhuman that will destroy us all.

Should we heed this warning that Klock finds in the Morrison of the 2000s—an echo of Bloom’s arrogation of the Western Canon to “selfishness and exploitation”? Or ought we simply celebrate with today’s genderfluid Morrison the dawning of the posthuman as the divine spark’s jailbreak from the ego and all other archons of this prison planet?

The question remains open. We all have moments—though for some the moment is a lifetime—when we do not feel at home on this alien earth. You can drive out gnosticism with a pitchfork, but she will always return.

In Chesterton’s book on Blake, the witty Catholic apologist chides the poet for exhibiting “the energy in the Gnostics who so nearly captured Christianity, and who were persecuted for their pessimism.” Yet Chesterton almost inadvertently catches his beloved “orthodoxy” in the net he spreads for heresy:

Let us, however, attempt to find a short and popular statement of the position of Blake and all such mystics. The plainest way of putting it, I think, is this: this school especially denied the authority of Nature. Some went the extreme length of the mad Manichæans, and declared the material universe evil in itself. Some, like Blake, and most of the poets considered it as a shadow or illusion, a sort of joke of the Almighty. But whatever else Nature was, Nature was not our mother. Blake applies to her the strange words used by Christ to Mary, and says to Mother-Earth in many poems: “What have I to do with thee?”

Those “strange words used by Christ” come from the Christian Bible itself (John 2:4), not some heresiarch’s excluded scroll. And even in canonical gospels less Platonic than John’s, Christ preaches against the natural, the given, the organic—preaches a doctrine James Lindsay would call “grooming”:

If any man come to me and hate not his father and mother, and wife and children, and brethren and sisters, yea, and his own life also, he cannot be my disciple. (Luke 14:26)

Vico is as popular with writers and literary critics as with sociologists and Marxists for his theory that poetry was the primordial human discourse and poets therefore the first founders of all human institutions.

Bloom doesn’t add—but some would—that in doing so Dante converts the crypto-Cathar love religion of the Troubadours, itself derived ultimately from the poetic mysticism of pre-Islamic Arabia, into the modern model of western epic and lyric, where it has since remained, and from which eminence it has shaped our understanding of psychological depth and change. Bloom’s recoil from the admittedly simplistic multiculturalism then in fashion led him to overlook some meaningful connections.

If you absolutely need to hear something like this from someone whose identity and cultural tradition can’t be dismissed as “white” or “European” or “elitist,” then try Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo and “Neo-HooDoo Manifesto.” Bloom places Mumbo Jumbo in his notorious canon but is elsewhere wary and dismissive of Reed, presumably detecting a backbeat of anti-Semitism in the novel’s multicultural critique of monotheism and the Word, just as there is in Myra Breckinridge, Gore Vidal’s nearly contemporaneous queer critique of Judeo-Christian sexual morality. In both The Book of J and The Western Canon, Bloom himself sagely neutralizes the anti-Semitic or at least anti-Judaic potential of a rebellion against the Hebrew Bible’s God by showing this scripture itself to be internally divided and heterogenous, with what he takes to be its oldest strand an ambiguous poetic narrative closer to gnosis than to normativity, thus preempting the gentile rebel against the God of Abraham with a primordial Jewish anarchy and aestheticism—a Kafka as the energetic fount of the tradition rather than its sad last babbling.