A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

First, in case you missed my column this week for Tablet’s Daily Scroll, the link is below. It concerns the long history of skepticism toward the Greek and Roman classics and how the study of these works might be justified anyway. A perennial theme of mine—one that both sides in the culture war should be made to acknowledge more—is that the call to abolish the western canon originates in the western canon. Marble-eyed Plato and great-bearded Tolstoy are woker than the woke. It should give everyone pause.

Things have been quiet on johnpistelli.com, but, having read Lawrence’s The Rainbow back in May, just before my Ulysses reread, I’m preparing an essay on The Rainbow’s celebrated sequel, often called Lawrence’s best novel, Women in Love. I have 80 pages of the book to go, and then the famous movie, and then some essays by luminaries from Joyce Carol Oates to Camille Paglia, and then I will be ready.

It’s too bad I don’t have Lawrence’s epochal Studies in Classic American Literature under review for the Fourth of July weekend, but that one I’ve mainly read in fragments. If you’re feeling patriotic, though, I’ve written essays through the years on a number of perennial candidates for Great American Novel. I’ll put in some links below:

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

William Faulkner, Light in August

Saul Bellow, The Adventures of Augie March

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow

Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon

Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

Over at the Grand Hotel Abyss Tumblr, I replied to two excellent pieces I recommend everyone read.

First is Tomiwa Owolade’s cogent objection to “decolonizing” the curriculum. In my riposte, I made a measured defense of reading Wole Soyinka over Philip Larkin on the grounds that the former, not the latter, is the universal rather than parochial poet; and I relished the absurd, almost unbelievable irony of removing postcolonial bard Seamus Heaney from the canon as a gesture of “decolonization.”

Second, right here on SubStack, novelist Autumn Christian wrote some highly energizing “rules for writing”:

I replied mostly to agree, though I did take issue with “find your voice,” advice I’ve always found misleading. I also ruminated on the flaws that prevent brilliant and talented writers from becoming great.

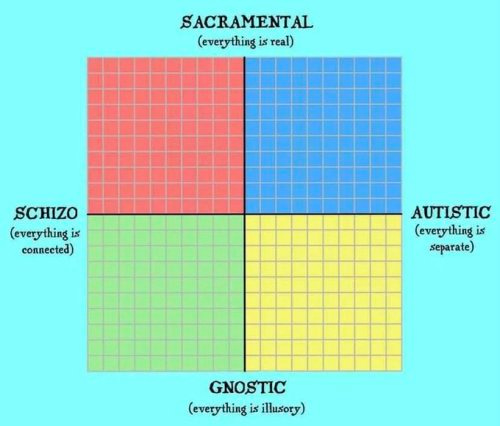

And now, if you need yet more to read for the long weekend, I’m going to take the liberty of reproducing an old Grand Hotel Abyss Tumblr post, one from back in January, right here. I wrote it casually, as a joke or jeu d’esprit, but the more I think about it, the more seriously I take it. The context is this: last summer, Twitter user @carmelittles repurposed the four-quadrant political compass to chart what are essentially theological sensibilities rather than political ones, though arguably the theological always underpins the political.

This meme passed through the internet in waves—I found it about six months after its creation—and was reviralized this weekend when provocatrice Anna Khachiyan posted it to her Instagram stories. I first saw it back in January and immediately thought it might be revelatory to apply to major writers, so I wrote the following:

We must start plotting great writers onto this immediately. Great writers, though, can’t be plotted statically on any chart, as they are torn between contraries, their agonies and travails being precisely what endear them to us. We would need to plot paths through time or to place different works in different places.

To take a recent example: Blake, whose early lyrics, still endeared to nature, are schizo-sacramental, and whose later epics, with their gonzo historiography, are schizo-gnostic. This works politically too, as he goes from support for the French Revolution to an anarcho-spiritual liberation of the mind. Almost the same journey is taken faithfully by Joyce, from his early naturalist fiction (written when he called himself a “socialist artist”) to his late work with its autonomous language (written in an avowed spirit of anarchism). If Blake and Joyce descend through the left quadrants, T.S. Eliot crosses the center, from the autistic-gnosticism of the early lyrics (“I can connect / Nothing with nothing”) to the schizo-sacramental of the late (“the fire and the rose are one”). Eliot’s example doesn’t track his politics as neatly, but if you think of it as going from fascist-sympathizing skepticism and vitalism to sober rational Christian universalism, it does work. In fact, the genius of this chart is that it reveals not politics but metapolitics.

Some individual works occupy multiple positions: Gravity’s Rainbow stretches across the bottom quadrants as Slothrop can’t decide if everything or nothing in this illusory world connects, just as Pynchon’s (and his generation’s) leftism and libertarianism abrade one another. Paradise Lost’s version of the Christian story explicitly narrates a three-part movement: from the status quo ante before man was created and the angels rebelled (schizo-sacramental) to Satan’s revolt and then the Fall of Man, which introduce pain, guilt, shame, and the inner life (autistic-gnostic), to the projected utopian future of Christ’s Kingdom where the world will be destroyed and, in a new heaven and new earth, “God will be all in all” (schizo-gnostic).

Who are some other favorites here at Grand Hotel Abyss? Cynthia Ozick: autistic-sacramental criticism, autistic-gnostic fiction. Toni Morrison: from implicitly autistic-sacramental early work (with its praise of metaphysical blackness) to explicitly schizo-gnostic later work (with its feminist universalism-in-diversity). Iris Murdoch: a three-way quarrel in her head between the Platonic philosopher’s autistic-gnosticism, the realist novelist’s autistic-sacramentalism, and the romancer’s schizo-gnosticism. Don DeLillo: the political paranoid in him is schizo-gnostic, the religious seeker schizo-sacramental. Saul Bellow: the autistic-sacramental prose style of a man longing for schizo-gnostic visions.

Some authors or modes are more easily positioned, I grant. Great realist novelists like Jane Austen and Tolstoy are autistic-sacramental (their characters are distinct and real—that’s what realism is), until you consider their implicit religious perspective, and then we start drifting into gnostic territory. Great fantasists like Kafka and Borges, by contrast, are autistic-gnostic (their characters are potentially deluded questers in a fallen, illusory cosmos), with only intimations of the real or the unified.

Susan Sontag would reprove us for using illness as a metaphor here precisely because she objected, early and late, to all schizo tendencies joining this to that (connections—metaphors—are the target of “Against Interpretation” as of Illness as Metaphor); yet as she moved from formalism in art and radicalism in politics to humanism in art and liberalism in politics over the course of her life, she crossed the line from gnostic to sacramental, both on the autistic side.

It occurs to me that schizo-sacramentalism is the rarest position, and the hardest to hold, either the paradise from which innocents like Milton and Blake and Joyce have fallen or the heaven that experienced men like Eliot and DeLillo can scarcely reach, though in theory it should be the default or orthodox position of any monotheist, sacred and profane. Marxism, for example, is an officially schizo-sacramental doctrine (the dialectical part is schizo, the materialist part sacramental), yet it’s constantly collapsing into gnostic chaos of various sorts. What does this tell us?

Finally, the very fact that I find this deranged parlor game to be a mentally aerating advance in thought can itself be plotted on the chart: evidence of my own schizo-gnostic tendency. Only connect, baby!

Thanks for reading—please stay tuned for more podcast content, please feel free to comment, and please be sure to like and subscribe.

I appreciate the thoughtful response to my post.