A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Reviewing the latest book by scholar John Guillory in The New Yorker, Merve Emre offers a history of modern literary criticism, from its 18th-century beginning in textual emendation through its 19th-century height as cultural prophecy to its 20th-century institutionalization as a body of expert knowledge modeled on the natural sciences.

Emre herself is a transitional figure, something like the last of the tenured (i.e., expert) critics, but one with a foot in appreciative literary journalism, popular nonfiction, and their social-media extension of the critical persona. Under the latter penumbra she is free, as the secular professional-expert is not, to say, for example, “Reading Jon Fosse’s Septology is the closest I have come to feeling the presence of God here on earth.”1

Backed by Guillory, Emre concludes by conceding that academia, however beset from hostile outside forces, has in itself failed the mission of criticism. It has encouraged its dwindling corps of professionals to have an inflated sense of their own importance even as they manifestly seethe with resentment about their actual social inutility.

Guillory suggests restoring aesthetic judgment to academic criticism, where the practice is largely banned as “unscientific” and therefore has to be smuggled in by the back door of political polemic—a practice universalized in the last decade, so that younger people of all ideological stripes delude themselves that they have made an aesthetic judgment when they pronounce X racist or Y woke or what have you. Emre urges readers to look elsewhere for the vital force of criticism, from little magazines like The Point to Amazon and Goodreads to podcasts and adult-education programs to the non-English-speaking world.2

No argument here—an argument here would be a performative contradiction. As my sabbatical from criticism continues, however, I renew my question from last week about how much of it we really need. Do I just miss the naïveté of childhood, when art that affected me inspired me to make art of my own? Or is there something to be learned from the child who ran from comic book to crayon? Harold Bloom, who followed Wilde in elevating criticism to the same plane as art, once wrote:

A poem is spark and act, or else we need not read it a second time. Criticism is spark and act, or else we need not read it at all.

“The Critic as Artist” passes this severe test, as its title boldly asserts. Bloom at his best does too, his best being neither the delirious theorizing of the ’60s and ’70s nor the dotage of the last two decades, but the popular aesthetic rhapsodies of the 20th century’s end centered on The Western Canon. How much else does?

For this week’s newsletter, I slightly cheat on my sabbatical—slightly cheat on my soon-to-be-serialized novel3—with a full sequel to the musings on Balzac from two weeks ago. Yes, I published the first of them on Tumblr recently and gave you the link last week, but according to my stats only two among the hundreds of my Substack readers clicked the link, so I’m putting it here too. The internet is almost unbelievably silo’d these days—Tumblr people read Tumblr, Substack people read Substack, Goodreads people read Goodreads, Twitter people read Twitter, etc.—so I refuse to be shy about posting everything everywhere. I write for no one and everyone.

“The Stunned Air Shudders”: Art and Magic Revisited

Speaking of, well, everything I’ve been speaking of lately—I am in a clanging and clamoring echo chamber of synchronicity, trying to hang on to this bit of dark wisdom from Coetzee’s novel about Dostoevsky: “he knows too that as long as he tries by cunning to distinguish things that are things from things that are signs he will not be saved”—I was less than halfway through the Art of Darkness podcast’s five-plus-hour episode on Aleister Crowley when one of the hosts declaimed a text I had no idea even existed. The magus, it turns out, once wrote a sonnet commemorating Rodin’s Monument to Balzac:

Giant, with iron secrecies ennighted,

Cloaked, Balzac stands and sees. Immense disdain,

Egyptian silence, mastery of pain,

Gargantuan laughter, shake or still the ignited

Statue of the Master, vivid. Far, affrighted,

The stunned air shudders on the skin. In vain

The Master of La Comédie Humaine

Shadows the deep-set eyes, genius lighted.Epithalamia, birth songs, epitaphs,

Are written in the mystery of his lips.

Sad wisdom, scornful shame, grand agony

In the coffin folds of the cloak, scarred mountains, lie,

And pity hides i’ th’ heart. Grim knowledge grips

The essential manhood. Balzac stands, and laughs.

It’s a bad poem overall—as my source for the text reports, Crowley thought himself a better poet than Yeats; compare this to “Lapis Lazuli” and get back to me—though I am not so small-minded as to disrespect the attempt at a Shakespearean coinage with “ennighted,” the otherwise apparently inexistent synonym-antonym of “benighted” (it seems to mean “endowed with obscurity”) and therefore (perhaps) a hapax legomenon. And “the stunned air shudders on the skin” is, I concede, gorgeous.

I illustrated a recent Substack newsletter with Rodin’s nude study of Balzac, which I saw at LACMA in 2012; the newsletter jumped off from Justin Murphy’s salute to ambitious young Balzac to consider later writers—Octavia Butler, Ray Bradbury—who used vaguely magical techniques of manifestation, affirmation, and visualization, the kind now viral on YouTube and TikTok, and descended, of course, from some of Crowley’s occult practices.4

Balzac knew all about it, as he writes in his mystical novel about an androgynous angel, Séraphîta, to which synchronicity also brought me, as I report in the newsletter’s footnote. It’s the most boring novel ever written, alas, scaling Nordic fjords of sententiousness I would not have thought possible. Camille Paglia pays it a lovely and lyrical tribute in Sexual Personae, assimilating it to her category of “androgyne as Apollonian angel,” calling it “the French Epipsychidion,” and noting that it was the favorite Balzac novel of—him again!—Yeats. And Balzac, as Rodin’s hand-eye rightly intuited, was not, like seraphic Shelley, himself an androgyne, but rather one possessed of “essential manhood.”

From Séraphîta, where Balzac writes, where Balzac’s eponymous and sexless seraph prophesies:

“Fruit of the laborious, progressive, continued development of natural properties and faculties vitalized anew by the divine breath of the Word, Prayer has occult activity; it is the final worship—not the material worship of images, nor the spiritual worship of formulas, but the worship of the Divine World. We say no prayers,—prayer forms within us; it is a faculty which acts of itself; it has attained a way of action which lifts it outside of forms; it links the soul to God, with whom we unite as the root of the tree unites with the soil; our veins draw life from the principle of life, and we live by the life of the universe. Prayer bestows external conviction by making us penetrate the Material World through the cohesion of all our faculties with the elementary substances; it bestows internal conviction by developing our essence and mingling it with that of the Spiritual Worlds.”

Which is to say: affirm, visualize, manifest. Or should we heed Coetzee: should we let the everyday rest in and as the everyday, a human comedy, untransfigured because all-transfigured, every inch God’s work?

“A Dead Wall of Paint”: The Artist’s Quest for Perfection

Following my dalliance with Séraphîta, I’ve been reading more of Balzac’s strange short novels. I’ll leave a discussion of The Girl with the Golden Eyes—from its 20-page prologue canvassing the classes of Paris to its bloody concluding tableau of lesbianism, murder, and implied incest—for some other time. But an account of The Unknown Masterpiece may be more urgent. Someone should have sat me down and forced me to read it 20 years ago. Both “modern art is degenerate” right-wingers and “modern art is a CIA psyop” left-wingers should read it without delay—only then will they amend their spiritual shallowness, their politicization of art.

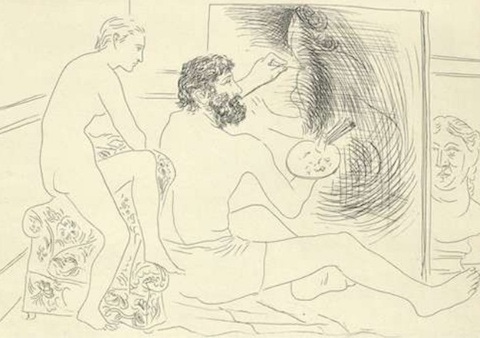

In this novella, Frenhofer, an obsessive master-painter of the 17th century, inadvertently invents modern art when he tries to include all of reality in his portrait of a beautiful woman. As this fictional painter’s real-life disciples Poussin and Porbus learn when they enter his studio and behold his canvas, Frenhofer has thereby annulled the picture as representation and produced instead only the apparent chaos of discordant perspectives and subjective notations anticipating everything from Impressionism to Cubism to Abstract Expressionism.

The portrait has a single remnant of realism: the sitter’s perfectly painted bare foot peeping from the painting’s corner, representing the literal ground from which the painting launched itself into the ideal, the heaven of art.5

They looked round for the picture of which he had spoken, and could not discover it.

“Look here!” said the old man. His hair was disordered, his face aglow with a more than human exaltation, his eyes glittered, he breathed hard like a young lover frenzied by love.

“Aha!” he cried, “you did not expect to see such perfection! You are looking for a picture, and you see a woman before you. There is such depth in that canvas, the atmosphere is so true that you can not distinguish it from the air that surrounds us. Where is art? Art has vanished, it is invisible! It is the form of a living girl that you see before you. Have I not caught the very hues of life, the spirit of the living line that defines the figure? Is there not the effect produced there like that which all natural objects present in the atmosphere about them, or fishes in the water? Do you see how the figure stands out against the background? Does it not seem to you that you pass your hand along the back? But then for seven years I studied and watched how the daylight blends with the objects on which it falls. And the hair, the light pours over it like a flood, does it not?... Ah! she breathed, I am sure that she breathed! Her breast—ah, see! Who would not fall on his knees before her? Her pulses throb. She will rise to her feet. Wait!”

“Do you see anything?” Poussin asked of Porbus.

“No... do you?”

“I see nothing.”

The two painters left the old man to his ecstasy, and tried to ascertain whether the light that fell full upon the canvas had in some way neutralized all the effect for them. They moved to the right and left of the picture; they came in front, bending down and standing upright by turns.

“Yes, yes, it is really canvas,” said Frenhofer, who mistook the nature of this minute investigation.

“Look! the canvas is on a stretcher, here is the easel; indeed, here are my colors, my brushes,” and he took up a brush and held it out to them, all unsuspicious of their thought.

“The old lansquenet is laughing at us,” said Poussin, coming once more toward the supposed picture. “I can see nothing there but confused masses of color and a multitude of fantastical lines that go to make a dead wall of paint.”

“We are mistaken, look!” said Porbus.

In a corner of the canvas, as they came nearer, they distinguished a bare foot emerging from the chaos of color, half-tints and vague shadows that made up a dim, formless fog. Its living delicate beauty held them spellbound. This fragment that had escaped an incomprehensible, slow, and gradual destruction seemed to them like the Parian marble torso of some Venus emerging from the ashes of a ruined town.

“There is a woman beneath,” exclaimed Porbus, calling Poussin’s attention to the coats of paint with which the old artist had overlaid and concealed his work in the quest of perfection.

Both artists turned involuntarily to Frenhofer. They began to have some understanding, vague though it was, of the ecstasy in which he lived.

“He believes it in all good faith,” said Porbus.

I was inspired to write at least a bit about The Unknown Masterpiece by a Tweet from art critic Jerry Saltz and its angry rejoinder by a new-right type.

According to Balzac, both Tweets are wrong. For artists, making art can’t be natural, can’t be automatic, can’t be an essential and unthinking aspect of their being, as breath is, but is rather a strenuous effort at transcendence, an attempt to breathe in a wholly different or alien atmosphere, an attempt to stand on something other than our feet. And because of this, skill and craft are too wholly this-worldly to suffice; the artist dreams of using them only to cancel them, as every real poet is trying to use language to raze language’s own communicative facade, to disclose what language conceals.

These modern ambitions may be tragic and unrealizable, may be mistaken, may be dangerously utopian, may have something even to do (I take this seriously) with Hitler and Stalin, with imperialism and nuclear war. Maybe we should go back to skill and craft and design, the replication of tradition, the ornamentation of humble lives—to being guildmasters rather than hierophants. Except that Goethe’s God in Faust promises to save all who strive; and Genesis’s God, at least as written by the impious and Kafkaesque poet Bloom hails as the author of The Book of J, seems to like it when we wrestle with him.

Fosse, like all advanced European novelists, seems to think paragraph breaks a mark of petit-bourgeois bad taste. Perhaps this belated scriptio continua made Emre think she was reading the New Testament in the original.

I was supposed to read Guillory’s classic Cultural Capital in graduate school, but I didn’t. The professor who ordered me to read it, a brash young postcolonial theorist with Ph.D. from Chicago fresh in hand, also sternly informed me that in academe making aesthetic judgments is, and I quote the Lady Bracknellish phrasing precisely, “not done.” Finally, he pointed out that Cultural Capital’s cover image—a photograph of a feminist protest where a banner reading “DICKINSON + WOOLF” was flown out a university window above a stone entablature carved with the names of dead white males like Cicero and Virgil—wrapped around the book so that the first four letters in the Belle of Amherst’s surname announced themselves loudly on the spine: DICK.

Among the obstacles to my serializing a novel: my always late discovery of a title. I named both Portraits and Ashes and The Quarantine of St. Sebastian House only after completing the first drafts. The Class of 2000 was different—I knew I would call the book that before I knew the book’s plot. But that title could apply to all my work insofar as my work has any generational element, similar to the way any given Roth book could be called The Human Stain or any Ishiguro titled The Unconsoled. I am trying to name this book as I’m writing it so I can show it to you before I finish, like a proper serial author. If my google search is to be believed, and I do find this hard to credit, no novel—not an unheralded masterpiece of mythic-method modernism nor a dark fantasy paperback from the ’80s—has ever been titled Major Arcana. I am considering it. What do you think?

Murphy has followed his Balzacian rumination with one on painter Francis Bacon, whose “violent focus” he commends. Of Bacon, he asks,

What would have happened to Bacon’s career had he been subscribed to nine podcasts? Had he been posting his work to Instagram, and Facebook, and Twitter? Pressure would have leaked from the pressure cooker and the violence of his work would have dissipated.

But Bacon was too much the hot-house flower—the same kind of 20th-century damage we see in Kafka and Beckett. Balzac’s energetic immersion in the world is the more admirable model; Balzac would have listened to nine podcasts, probably at the same time, while swilling nine cups of coffee. I can’t recommend The Art of Darkness podcast with Kevin Kautzman and Brad Kelly more highly, by the way; I literally haven’t listened to any other pod in 2023. I’m listening to it, in a way, for “research,” or at least as a kind of mood board, filling my head with the scandalous lives of artists, the better to compose my own fictional one in Major Arcana or whatever it’s called. They have episodes on high-canonical monuments (Joyce, Woolf), literary celebrities (Wilde, Nin), countercultural icons (Crowley, Burroughs), genre superstars (Lovecraft, Herbert), neglected experimentalists (Kane, Kavan), and more, along with a roster of guests from clear across the ideological spectrum. They even have a Francis Bacon episode, but I haven’t arrived at it yet.

If I rightly recall a book I prized in my adolescence, The Intimate Sex Lives of Famous People, Balzac was, biographically speaking, a podophile, but it symbolically has to be a foot anyway. As Bataille explains in his essay “The Big Toe,” the foot, in its cloddish abasement, its essential humanness, signifies the erotically appealing debasement of our spiritual aspiration. It is the most human part of the human body. The non-prehensile but nonetheless earthbound big toe emblematizes our tragicomic bipedal equidistance from both angel and ape. Foot fetishism, therefore, is the normative paradigm of human sexuality.

Great! I was also very taken by the Merve Emre piece. Very interesting what you're saying - how bizarre it is that aesthetic judgments are verboten in the academy. Something that definitely bothered me as an undergrad; I think you're right that it's symptomatic of a larger issue.

I've read much of Harold Bloom--so prolific and powerful. Going up against him and to great interest and controversy is Cynthia Ozick in _Art and Ardor_, particularly her essay "Literature as idol: Harold Bloom"—fascinating. I'm wondering if you've read her?

I'm also going to send you a personal message from my personal email: <mltabor@me.com>. New idea coming ...