A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

I’m focused on writing fiction at the moment, starting the New Year slow as far as criticism is concerned. I have, to be honest, even begun to doubt the mission. Does a world that barely reads at all benefit from another critical essay? Mine are widely read, more widely than those of establishment critics, and I’m certainly grateful for that, but at what point does discourse about art, especially when it’s so caught in the tangle of politics, begin to eclipse art—become an excuse not to make art?

In a 2015 profile, Kazuo Ishiguro explained his relative absence from political debate, unlike such controversial contemporaries as Martin Amis. He had been asked at the beginning of his career to write an opinion piece about the atomic bomb’s relation to literature, so he dutifully came up with a thesis about the exploitation of the event for gravitas’s sake of by writers with no relation to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The profile continues:

It sounds pretty plausible and, indeed, he thinks it was pretty well written. “But this was something I hadn’t been going around fuming about, or even thinking about until I got asked.” He laughs. “But if you read that piece now, you’d think I had; a guy who was born in Nagasaki who felt the whole nuclear thing had been exploited by people just trying to lend spurious weight and seriousness to their otherwise rather banal piece of fiction.”

After that experience – quite the reverse of what happened when he wrote fiction – he realised that “if I keep doing this, I won’t know who the hell I am. I’ll just be a sum total of these positions that I’ve taken up to fulfil commissions.” Instead, he decided that he’d be better off spending the time working out what really interests him – and has spent the following 30 years doing precisely that.

Ishiguro’s stated political opinions are exquisitely banal, not an inch before or behind progressive bien-pensance. The worldview suggested by his novels—a kind of stoic and sometimes even cheerful nihilistic quiescence—is quite different.

I don’t have that kind of discipline—I like controversy and the idea of the writer as a character in public drama—but, still, isn’t he right? And as the urgency seems to drain from the culture war,1 smuggling otherwise unsayable social and political commentary into literary criticism loses its thrill, though I had a lot of fun doing it in the last decade in pieces on everything from Sense and Sensibility to Myra Breckinridge. If the metropolitan avant-garde turns to literal race science, then warning the academic avant-garde to place a little less stress on the racial component of artistic composition comes to sound merely sensible rather than, as it sounded from 2012 to 2022, dangerously reactionary.

The future of literary criticism, of literary discussion, if not simply its present, might be the oral tradition: YouTube and podcasts, recreations in the wilderness of a classroom that either no longer exists or has no wilderness within it.

For our weekly newsletter below, I offer two brief pieces from the Grand Hotel Abyss Tumblr, one pasted in verbatim and one more than doubled in length. I’ve been more active over there lately since readers have been using Tumblr’s “Ask” function to solicit my views on a number of subjects—you can do it too—and the first of these little essays was written in answer to just such a question.

Palpable Design: Science Fiction vs. the Novel

An Anonymous reader of my Tumblr asks the following question:

You seem apprehensive about science fiction, generally, with some exceptions (Herbert, Le Guin, Kavan) Care to speak a bit more about what the genre does and doesn’t do for you?

I replied: I think I mostly gave good reviews to everything in the genre I’ve written about, but you’re right that something in me hesitates.

I grew up with the genre. Influences still linger from my childhood: Heinlein sparked my interest in the literature of ideas, Bradbury turned me toward aesthetic prose, and Ellison modeled the writer as pugnacious public force. (Asimov and Clarke didn’t interest me then, just as Kim Stanley Robinson doesn’t interest me now. I’ve never cared about actual science, except maybe for the very idea of theoretical physics, which, sans the math, just returns us to speculative philosophy anyway.) I discovered Dick, Delany, Le Guin, Gibson, Ballard, and Butler later, mostly in college; I even interviewed China Miéville once—circa Iron Council—but didn’t keep up with his career after that. I love Tom Disch’s acerbic and more-than-apprehensive history of the genre, The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of, a real essay in the old liberalism equally dismissive of Heinlein’s Kiplingesque militarism and Le Guin’s Rousseauist pacifism. He would, had he lived, have made a good anti-woke pundit. I still haven’t read his fiction.

While science fiction and fantasy both get dumped in the “genre” bin with romance and detective novels, they are infinitely freer genres, since the conceit of imagined futures, imagined worlds, imagined technologies, or imagined aliens makes no plot demands in the way that romance and detective novels require certain story structures, however subverted. In that way, science fiction isn’t a genre at all but a mode (related to satire and utopia) requiring that other genres be grafted on to create a novel proper, whether noir (Neuromancer), historical romance (Dune), boys’ adventure (Starship Troopers), slave narrative (Kindred), imperial romance (The Left Hand of Darkness), etc. You can do (almost) anything in science fiction.

Yet “related to satire and utopia” is the catch: the source of my hesitation. There is something irreducibly ideological in the genre, “ideological” not in the Marxist sense of “hidden structuring assumptions that uphold vested interests” but in the liberal sense of “willful and reductive systematic reasoning.” Why would anyone imagine a future, a world, a technology, an alien, if not to make a point? Science fiction by its nature has “a palpable design upon us.” Some writers can use this to advantage, as in Solaris, a genuinely searching essay, but the risk of didacticism is sky high.

You can’t write a novel in the Jamesian sense—a shaped record of inner sensibility encountering outer experience in the present—within science fiction, because it asks for the totality of your views on nature and society up front without letting them emerge slowly from the artistic process itself and therefore surprise you as much as the reader. I have tried to write science fiction as an adult, and every time, I bog down in exposition, losing myself in the composition of a political treatise before I can meet a character or see a sight. My own lack of capacity should be blamed first, but not solely. So if I ever seem to think science fiction per se falls short of art, that would be the reason.

Live Forever: Writers Making Affirmations

The controversial renegade para-academic Justin Murphy derives several lessons for artists and thinkers from André Maurois’s Balzac biography, significantly titled Prometheus. I would like to focus on one. As Murphy elaborated on Twitter, the following passage from Maurois—

He was the only one to imagine a great future for himself. In the eyes of his teachers and peers, he remained an ordinary student, remarkable only for his appetite for printed paper and a presumption that nothing seemed to justify.

—inspired him to say,

Allow yourself delusions of grandeur, if they motivate you.

Who cares? If you fail, whatever, at least you dared to be great.

Balzac thought he was destined as early as grade school, and it propelled him.

Good advice. Balzac, the realist beloved of the Marxist materialist, was himself a mystic, a Swedenborgean. Accumulating knowledge “quickly and recklessly,” another anti-rule Murphy finds in Balzac’s biography, I found this article, summarizing the occult worldview of Balzac’s under-read novel, Séraphîta:2

As one character muses, the word may forever try to constrain nature, but nature always exceeds the word; however, at the same time, words are capable of “carrying [nature] up to a third, a ninth, or a twenty-seventh power … obtain[ing] magical results by condensing the processes of nature.” Language strives ever onward to capture the world—and thus will always proliferate names—but in so doing, it potentiates and intensifies the world by means of “a mysterious optic which increases, or diminishes, or exalts creation.” Names are “acting upon [us] at times like the torpedo which electrifies or paralyzes the fisherman, at other times like a dose of phosphorous which stimulates life and accelerates its propulsion.”

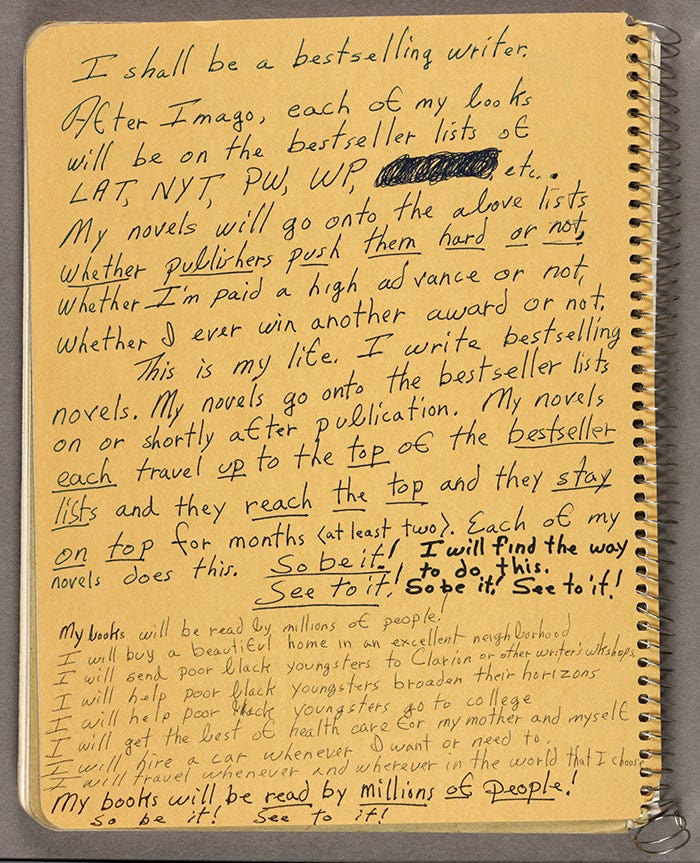

To take a more recent example, and to atone for my disparagement of science fiction above, secular critics have been admirably decorous about discovering in Octavia Butler’s archive that she was a manifester, a visualizer, a veritable law-of-assumptioner, writing affirmations—just as TikTok witches and YouTube Neville Goddard coaches advise—alongside the plans for her novels in her notebooks. E. Alex Jung, writing in Vulture, summarizes her practice:

The possibility that you could control the circumstances of your life with your mind held a strong appeal for Butler. She believed in its real-world application, too. She had begun taking self-hypnosis classes back in high school and devoured self-help books like The Magic of Thinking Big and 10 Days to a Great New Life. She particularly loved Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich, a book of motivational practices cribbed from the French psychologist Émile Coué’s concept of optimistic auto-suggestion, which originated the mantra “In every day, in every way, I am getting better and better.” She would learn to manifest.

I will give one more example, again by way of apology, from the domain of science fiction: the genre’s reigning poet, Ray Bradbury. Dana Gioia, more literally a poet, once wrote a persuasive essay with this thesis:

For one astonishingly productive decade—from 1950 to 1960—Ray Bradbury was probably the most influential fiction writer in the English language. Please note that I’m not claiming he was the best writer or that he exerted the most influence on his fellow writers. In strictly literary terms, Bradbury was not remotely the equal of Flannery O’Connor, Graham Greene, Chinua Achebe, John Cheever, or a dozen other of his Anglophonic contemporaries. Bradbury’s enormous impact was felt mostly outside the literary world—on scientists, filmmakers, architects, engineers, journalists, librarians, artists, and entrepreneurs. Above all, his influence was felt on the young, the generation of adolescents who would shape the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Bradbury’s impact is still evident from Disneyland to Cape Canaveral, from Hollywood to Silicon Valley.

I find this claim for Bradbury’s anti-literary effect on his readers ironic, because he affected me in just the opposite way.

It was one of the most memorable reading experiences of my life. When I was a child and adolescent, I used to read on the school bus during the long stretch between when it picked me up and when it picked up anyone I knew. And on one cold morning in the sixth or seventh grade, I read The Martian Chronicles, “‘—And the Moon Be Still as Bright,’” to be specific, a story titled after a line from Byron: that atmospheric tale of imperial nostalgia, where astronauts fecklessly wander the Romantic ruins of a dead Martian city, its inhabitants inadvertently exterminated by the chicken pox an earlier earth expedition carried, until one of the crew members snaps from the shame of it.

The party moved out into the moonlight, silently. They made their way to the outer rim of the dreaming dead city in the light of the racing twin moons. Their shadows, under them, were double shadows. They did not breathe, or seemed not to, perhaps, for several minutes. They were waiting for something to stir in the dead city, some gray form to rise, some ancient, ancestral shape to come galloping across the vacant sea bottom on an ancient, armored steel of impossible lineage, of unbelievable derivation.

And I understood for the first time, at the age of 12 or 13, after years of reading novels and comic books and watching movies for exciting stories, that mood and style finally matter more than plot. Bradbury didn’t make me want to be a scientist; he made me want to be a poet.

I bring it up because Bradbury thought as Balzac did, as Butler did. In a marvelous interview from 1972—I think Walter Kirn linked it on Twitter, but I’ve been watching it every so often as a pick-me-up since at least 2012, despite all the things he says I don’t agree with, which, who cares?—the writer explains his worldview, summed up in the repeated phrase, “Live forever.” The key is this:

So I discovered early on if you wanted anything, you went for it—and you got it. And most people don’t ever go anywhere or want anything, so they never get anything.

The words to object come easily to the critic. But would this have surprised Balzac? I doubt it. Great writers insisted they were great writers; they called upon angels and ministers of grace to help them align material with ideal, as the epic poet invoked the muse. Not all—not Kafka, for example—but plenty. Why, if not to gratify our own timidity, should we wish they had been more modest?

For example, this week’s New York Times op-ed about ditching Red Scare focused on Alex Jones and the vaccine question, and didn’t even mention the girls’ sometimes literal flirtation with Steve Sailer—whereas three years ago the latter would have been a nuclear flashpoint.

Synchronicity: this is the second time I’ve come upon Balzac’s Séraphîta in less than a month, which means I should read it. The first time was when I heard Victoria Nelson, author of the great Secret Life of Puppets, say she was adapting it into an opera on the Weird Studies podcast. So far, I’ve only read the one Balzac book everybody reads (Père Goriot), the one Balzac book acclaimed as his masterpiece and locus classicus of French realism (Lost Illusions, which I wrote about here), and the one Balzac novella (Sarrasine) every student of literary theory is made to read because it was the material (“the pensive text”) Roland Barthes fed into the poststructuralist perpetual-motion machine that is S/Z: An Essay. Prometheus, however, demands still more attention.

My problem with science fiction that has not been Bradbury or Le Guin has been that most of what I've come across (no naming of names) doesn't achieve, as it promises, what I like to call "heightened reality" that all fiction that I'm willing to call "art" achieves. The story needs to tell the underbelly story, the story we never tell anyone and that all great stories deal with.

Here's an example of what I mean:

“Yet, watching Creole's face as they neared the end of the first set, I had the feeling that something had happened, something I hadn't heard. Then they finished, there was scattered applause, and then, without an instant's warning, Creole started into something else, it was almost sardonic, it was Am I Blue? And, as though he commanded, Sonny began to play. Something began to happen. And Creole let out the reins. The dry, low, black man said something awful on the drums, Creole answered, and the drums talked back. Then the horn insisted, sweet and high, slightly detached perhaps, and Creole listened, commenting now and then, dry, and driving, beautiful and calm and old. Then they all came together again, and Sonny was part of the family again. I could tell this from his face. He seemed to have found, right there beneath his fingers, a damn brand-new piano. It seemed that he couldn't get over it. Then, for a while, just being happy with Sonny, they seemed to be agreeing with him that brand-new pianos certainly were a gas.” — “Sonny’s Blues,” James Baldwin