A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

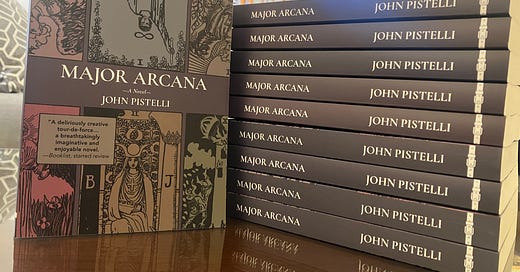

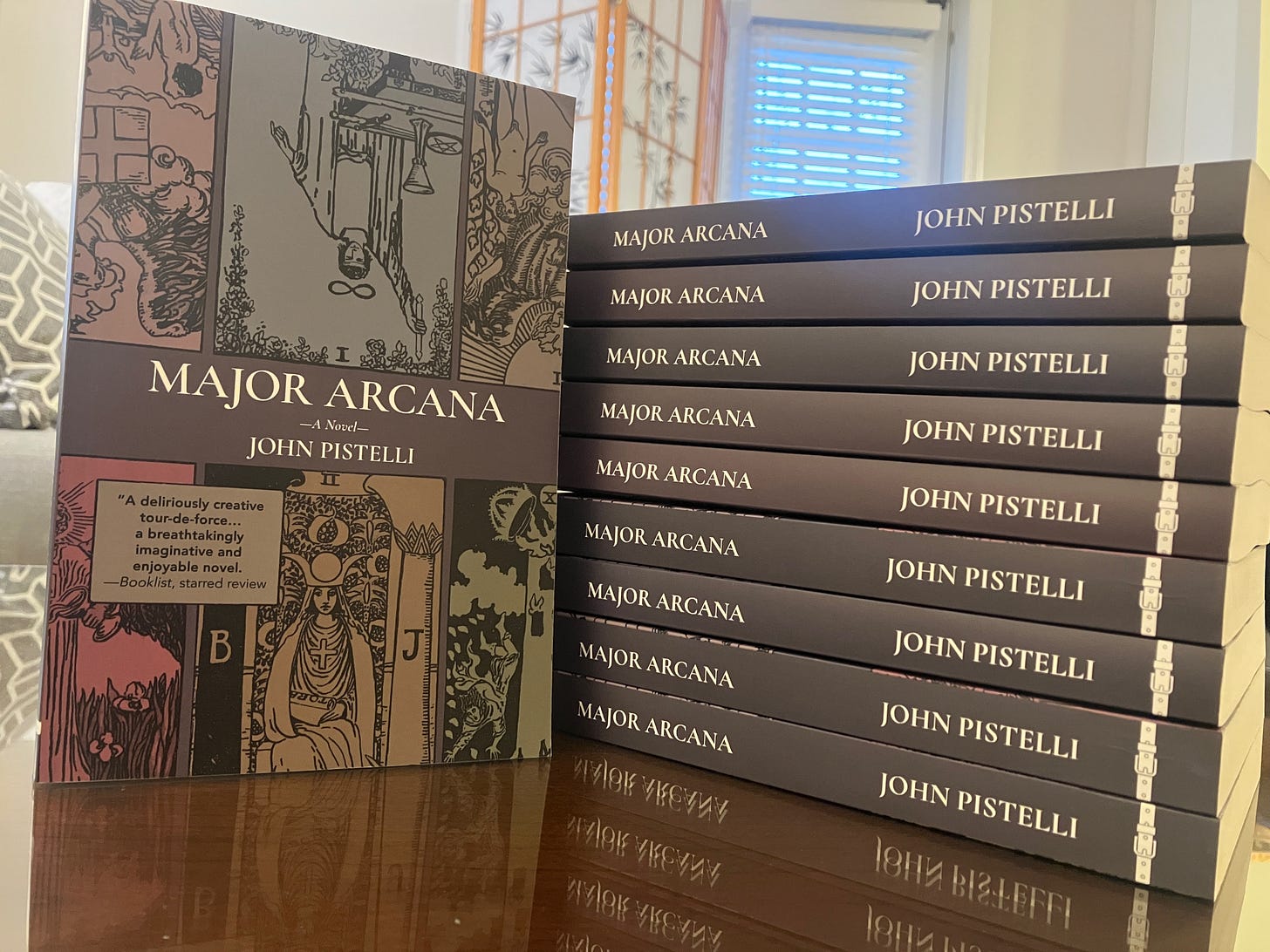

Welcome to this week’s many new subscribers, whether you’ve found your way to Grand Hotel Abyss from my centenary essay on the Keatsian beauty of The Great Gatsby in The Metropolitan Review, my vision of the past and future of the university for The Republic of Letters, or Henry Oliver’s kind words here, pursuant to Naomi Kanakia’s here, about my forthcoming novel Major Arcana. Major Arcana will be released on April 22 and can be preordered here in print and ebook formats; you can also preorder the audiobook, which will arrive on May 22. I will be appearing at Riverstone Books in Pittsburgh’s storied Squirrel Hill neighborhood for the novel’s release event next week—on April 17 at 7PM.1 The event is free: please register here! I will announce details about a New York appearance in early May as soon as all the details are finalized. Thanks to everyone who has preordered or reviewed the novel! Henry Oliver writes,

His new book Major Arcana is a strange, compelling novel. It is original and bizarre. You will be absorbed by it and challenged to think.2 Oh, and he’s a white man. Major Arcana is out in a couple of weeks. If you are truly worried about male novelists, pre-order it, read it, pass it to people you meet, write a review.3

My other major project also continues: The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers.4 This week I released “Instead of Dialectics, There Was Life,” the second of a two-episode sequence on Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment for our spring series on western world literature in translation. Previous series, which paid subscribers can access in the archive, focused on modern British and American literature, the works of James Joyce (especially Ulysses), George Eliot’s Middlemarch, and ancient Greek literature and philosophy. There are upcoming episodes on Tolstoy, Chekhov, Ibsen, Proust, Rilke, Kafka, and Borges in spring and upcoming series on Shakespeare and Milton in the summer and on the modern American novel in the fall.

For today—if you’re new here, the Weekly Readings are totally free and contain, after a self-promoting preamble, a somewhat cursory main text with copious and often incendiary footnotes—a response to a question about how writers might age gracefully. Please enjoy!

Massacre of the Masters: Literary Reputation and the Question of Self-Parody

Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre.

—Philip Roth, EverymanSomeone recently wrote in to ask me the following, after Thomas Pynchon’s new novel was announced, with perhaps the subtext that I, too, along with some others on this platform, was recently if gently accused of a certain “lowcowification”:

With many Pynchon heads like Logo feeling so lukewarm about the new book, it made me think—is becoming “corny” or not hip anymore a fate that no one can escape? Does it cast a shadow of any works or even thoughts one could do, because they all might be just be as empty as a grandpa screaming at the tv about how we should nuke that or other geopolitical foe?

There’s a real life-cycle to the artistic reputation. Major writers initially seem beguiling, mysterious, and unexpected when they first comes on the scene; then they take their sensibility and their materials to the utmost in a few superior works; then their motifs and tricks and anecdotes and biographical lore become familiar and then over-familiar, “there he goes again,” etc., and then, usually when we’re all sick of them, they die. Often writers’ reputations are at a low ebb just before and just after their deaths. It takes a new generation to come around and pick them back up. Your contemporaries are rivals, sycophants, fellow travelers, or members of the opposing party: their judgment is not enough to make a permanent reputation. Your immediate successors are even less trustworthy, since they are almost obligated to strike you down at the crossroads to make space for themselves. Only the third generation following you really begin to make the canon.

Look at the things major critics of her generation or the one just following (Wood, Bloom, Amis) wrote about Iris Murdoch, “another inscrutable over-populate plot, more Simone Weil ethics, there she goes again,” circa 2000 vs. now, when she’s regarded, especially here on Substack, as obviously one of the great geniuses of the 20th century.5 Everybody was sick of Sontag, too. Somebody said she belonged to literary history rather than literature, and now here she is, a permanent fixture.6 Even “problematic men” get their due, though, as with Updike. First, it was “good riddance to that priapic Protestant,” but now he receives appreciation from critics we might expect to be hostile, like Patricia Lockwood.

This reputational life-cycle intersects with or is based on the personal life-cycle; one hardens a bit, inevitably, with age, which means one’s art gets stiffer and more brittle in one’s twilight years, the obverse of the process by which it earlier solidified into individuality after early-adult beginnings that we all heterogenous potential. Don DeLillo, for example, had the purest form of that arc from the promising amorphousness of the 1970s novels to the supreme individuation of the 1980s and 1990s novels to the late mannerism of the 21st-century books. I would say, complicating examples aside, that Virginia Woolf, Toni Morrison, and Cormac McCarthy had similar journeys. There are counterexamples, obviously, like Philip Roth (fully accomplish debut, long middle period of exploratory failures, individuation in the late, almost the latest, work) or Kazuo Ishiguro (a steady state of accomplishment from early to late, with one or two failed experiments along the way) or Ralph Ellison (an early individuation so total he never recovered from it).

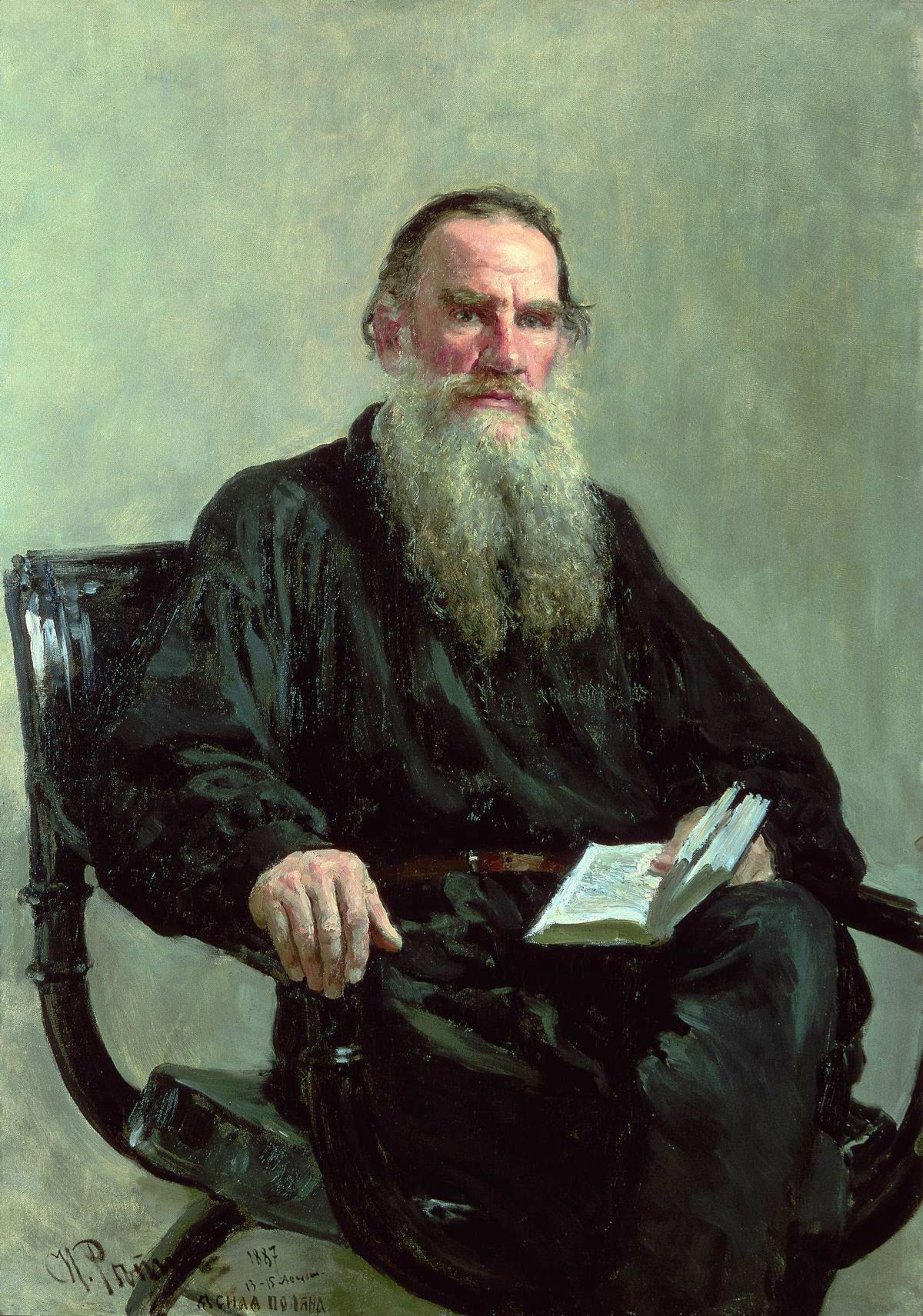

Dostoevsky is both a curious case and the best-case scenario: he just got better and better, with his final work as his supremest masterpiece. This is also true to a point of George Eliot, despite a few false starts between the Mill and Middlemarch, and, of Charles Dickens, and, what renders her relatively early death such a tragedy, of Jane Austen, whose final novel reads at times like Virginia Woolf. Most other people for reasons extrinsic and intrinsic to their art have to flail a bit (Herman Melville, Gustave Flaubert, Leo Tolstoy).7 Some people fall off (William Faulkner, for example). Ernest Hemingway, though by now we’d blame his brain injury, is the paradigm of collapsing into self-parody; but, brain injury aside, the style he started with, while revolutionary, didn’t leave a lot of room to maneuver, let alone to grow. His was a minor version of what Henry James, James Joyce, and Samuel Beckett each majorly “accomplished”: they followed the style they started with into its almost unreachable final extremity, which is not quite self-parody, but is often unreadable. The method of Finnegans Wake is already contained in nuce in the radiant polysemy of those two strange words everyone has to look up in the first paragraph of “The Sisters”—gnomon, simony—but that doesn’t mean we’d rather read Finnegans Wake than Dubliners.

Is there any way to avoid the fate of self-parody? Of the writers I’ve already named, Woolf and Ishiguro took the severest measures, even at the risk of gimmickry. Woolf chose a different style for almost every novel she wrote, everything from the stream of consciousness for which she’s best known in Mrs. Dalloway to the mock-biography of Orlando to whatever The Waves is. Meanwhile, Ishiguro, who always writes the same story in the same style, chose a different genre for each book. Ishiguro has what is simultaneously the most diverse and the most monotonous oeuvre of any major novelist. It’s always an emotionally repressed protagonist in a socially oppressive setting described in decorously plain prose, but it’s never the same person in the same place twice. He’ll give us painters, butlers, pianists, clones, robots, and knights of the Round Table, everywhere from medieval England to postwar Japan to late-20th-century Central Europe to future America, just to avoid repeating himself at any but the thematic level.

I probably couldn’t go to quite these lengths to escape “the history of styles.” Probably I will trust the changing times to change my work8 without my having to come up with strenuously ingenious conceits. Aging, like everything else, is probably not best accomplished in a state of crippling self-consciousness but rather by taking each day as it comes and making the most of it.

The other day I noticed this extremely disturbing graffito a few blocks from the venue:

This is a terrifying synchronicity not only in relation to Major Arcana’s occult and even parapolitical themes but also to my own occulted connection to our late satanic colonel, a topic first broached in my essay on Foucault’s Pendulum, a riddle I solved once and only once on a paywalled episode of Katherine Dee’s podcast in 2021, the answer being of special interest to devoted Invisible College listeners. Dark forces stalk the land. “Be cool,” as the poet said, or, in another synchronicity, and as another poet said, “Keep cool but care.” I hesitate to post what follows because I suppose it amounts to an accusation, though of what I’m not sure, but I also saw another graffito recently in urban Pittsburgh—

—one suggesting not only that print and bookstores are back, but also that people are spraypainting shitposts onto concrete infrastructure rather than putting them online.

A new review on NetGalley sharply observes of the novel’s themes,

While it might sound reductive, one surprising layer I found beneath its alluring surface—tarot cards, Dark Ages DC comics, and manifestation mysticism—is a kind of meta-narrative about the potential redemptive power of the literary canon in our postmodern world, one increasingly dominated by radical theories and philosophies.

while Locus Magazine writer Ian Mond also kindly adds, on Substack Notes,

While there is really no limit to the number of copies of Major Arcana you should order, and while I would not object to your ordering them for any reason within the bounds of law and moral custom, I would probably not, if I were you, order them on the basis of the author’s identity, such as it is. As Naomi points out in her piece linked above, the injunction to “read books by [X] identity group,” besides being an unpleasant moral blackmail, and besides further carrying the unsavory implication that all members of the specified group are interchangeable, also cannot create real, lasting power in the arts, which is based only on an audience attracted to the work without compulsion, and therefore also based only in the end on the quality of the work. Major Arcana would also make a poor mascot for the cause of an identitarian literature, since it persistently questions the idea of identity. The outcry about the real or perceived marginalization of men in literary fiction resembles this century’s other outcries against the marginalization of other groups in that the stake seems to be one’s ability to represent one’s experience authentically. The last thing I want to write or read about is anyone’s “authentic experience,” whatever that is, mine or yours. Major Arcana was written in part as a protest against this reduction of the novel to testimony or the “lived experience” of one’s group. It was written from within a broader and older tradition, a tradition that understands the mission of the novel to encompass as much of contemporary reality and all the people who live in it as the author can manage, including people quite different from the author, or people superficially different but startlingly similar under the surface. In this tradition, nothing could be more common than for male writers to write female protagonists and female writers to write male ones, and so forth across many lines of difference. This is the novel as it was written by Austen, Dickens, Hawthorne, Eliot, James, Wharton, Cather, Joyce, Lawrence, Woolf, Murdoch, Morrison, DeLillo, Ishiguro, and more, a tradition rooted ultimately in Shakespearean drama. Their novels contain many dimensions of experience, some the authors lived, some they observed, and some they only imagined. But, in the end, everything in a novel has to be imagined, even the things the novelist has experienced and observed, because if experience and observation were all it took to write a Middlemarch or a Ulysses, then everybody would write one. There are many wes our Is can form; gender and race are important ones, but hardly the only ones, and also hardly insuperable barriers to an attempt at understanding. I will quote the famous passage from a letter by Keats at almost its full length:

As to the poetical Character itself (I mean that sort of which, if I am any thing, I am a Member; that sort distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which is a thing per se and stands alone) it is not itself—it has no self—it is every thing and nothing—It has no character—it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated—It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity—he is continually in for—and filling some other Body—The Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute—the poet has none; no identity—he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God’s Creatures. If then he has no self, and if I am a Poet, where is the Wonder that I should say I would write no more? Might I not at that very instant have been cogitating on the Characters of Saturn and Ops? It is a wretched thing to confess; but is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature—how can it, when I have no nature? When I am in a room with People if I ever am free from speculating on creations of my own brain, then not myself goes home to myself: but the identity of every one in the room begins so to press upon me that I am in a very little time annihilated—not only among Men; it would be the same in a Nursery of children…

In A Room of One’s Own, Woolf, with reference to gender, makes the same point:

And I went on amateurishly to sketch a plan of the soul so that in each of us two powers preside, one male, one female; and in the man’s brain the man predominates over the woman, and in the woman’s brain the woman predominates over the man. The normal and comfortable state of being is that when the two live in harmony together, spiritually co-operating. If one is a man, still the woman part of his brain must have effect; and a woman also must have intercourse with the man in her. Coleridge perhaps meant this when he said that a great mind is androgynous. It is when this fusion takes place that the mind is fully fertilized and uses all its faculties.

Toni Morrison, from Playing in the Dark, draws a general conclusion in this area:

The writer’s ability to imagine what is not the self, to familiarize the strange, and to mystify the familiar—all this is the test of her or his power.

And in an interview, challenged on his frequent use of narrator-protagonists unlike himself—female, for instance, or white, or younger or older or of a different class or a different profession—Kazuo Ishiguro returns us to the distinction with which Keats began:

If you look at Wordsworth, it’s difficult to get away from the self: the big subject is Wordsworth. But if you’re in the Shakespeare tradition it’s easier to write from the point of view of character, which involves different sexes, different ages and different classes.

Even the most universal-seeming vision will necessarily be incomplete, and must include an acknowledgement of its incompletion, which we call irony, but this is no reason to excuse oneself from the attempt.

I gratefully note the following testimonials from the comments section of my Republic of Letters essay. First, there is Matt:

I’ve been subscribed to John since last January when the project officially started and as someone who is a mere babe in the woods of literature the Invisible College has completely changed my life.

Not only do I feel that I can engage with the foundational works of the Canon on their own terms, but I feel now more than ever how alive these books are. Without a single test, essay, or homework. Not only that, but the replay value for each episode so high. I’ve listened the Ulysses series probably about 5 times over now, each time revealing something new and profound.

I confess I’m quite Evangelical about the invisible college to any of my literary minded and non literary minded friends alike. Highly, highly, recommend.

Second, Harold:

If it means that more smart teachers of literature, like John, create their own Invisible Colleges I’m all for it. John Pistelli’s Invisible College is a treasure! His courses teem with knowledge, insight, provocation, humor, and most important—joy. As a first time Ulysses reader, John’s courses helped me understand and actually enjoy a book I was previously force-marching through. His courses on Moby Dick, a book I know well, brought new depths of analysis and connections which made that beautiful mess of a book all the more pleasurable.

What John has done seems like a natural and healthy way forward. His lectures carry a weight of responsibility—one senses he’s putting his ideas out there for competition and thus he takes the work seriously, and at the same time I sense a level of freedom in his approach that may flow from his knowing this is all his own creation. He’s clearly having fun which makes the courses all the more infectious for the listener.

Don’t miss Mary Jane Eyre’s ongoing philosophical fiction, The Iris Murdoch Book Club, the most recent installment of which dropped this week:

‘What do you think of the little bromanticist movement blossoming on Substack? Gasda, Barkan, Pistelli, Franz, Kumin, Jennings, Smith-Ruiu, et cetera?’

MJE also wrote the first and still most comprehensive review of Major Arcana when the Substack serial concluded.

My most far-reaching statement on gender and modern literature, it occurs to me, is contained in my long hatchet-job review of Benjamin Moser’s Sontag biography. I wrote it seven years ago, in somewhat different ideological circumstances, but I stand by the main point, one inspired by my academic lineage in the work of literary theorists concerned with the neglected and divergent female literary hegemonies first of “domestic woman” (19th century) and then of “exceptional woman” (20th century). I argue in the Sontag piece that in the 21st century we have experienced a stifling bureaucratization of the domestic to which an ethos of exceptionality, for all that it too could be criticized, might be a useful riposte, for authors male, female, and otherwise. In other words, the concept of genius still has its uses—and not only its uses, but a feminine as well as a masculine tradition.

The aforementioned Pynchon might fit in here: stupendous debut followed in a little over a decade by supreme masterpiece, then silence, and then a lot of books I’ve mostly never read, all of which have their partisans, none of which has really attained the status of Gravity’s Rainbow, with the announcement of the new one sounding like a self-parody of a sort, as Anna Krivolapova amusingly pointed out:

(If you can overcome your liberal guilt about marginalized men long enough to buy a recent book written by a woman, it really should be Krivolapova’s extraordinary debut, Incurable Graphomania, which I wrote about here. Ironically, I discovered this particular Anna K. from the circle Matthew Sini adduces in UnHerd—see here—as evidence that “the literary man is not dead,” though he is, like the current president, right-leaning and podcast-inclined.)

Then there’s the question of supernatural inspiration, what Socrates calls “divine frenzy.” I believe in this, to a point. Certainly it feels sometimes, in the best moments, that I am more discovering than inventing, more channeling than expressing. We’re all so prolific that I have only just caught up with Blake Smith’s wise essay from last month on this subject, “The Ugly and Beautiful Gods,” on James Merrill and Gary Snyder in particular, late instances of the Stevens vs. Pound sensibilities in (post)modern poetry. I confess I can’t muster much interest in Snyder, but now that I know from Blake’s essay that the spirits told Merrill essentially the same thing the aliens told Grant Morrison, which is essentially the same thing the mushrooms told Terence McKenna, I feel both abject cosmic fear and a renewed desire to read The Changing Light at Sandover. Anyway, Blake, taking his stand with a rare and ludic text of Snyder’s about Smokey Bear, counsels not spiritual psychosis but that we accept the provisionality of revelation:

The poet/prophet who knows himself to be one is not one. Rather, our whole culture is a continual churning out of which myths long forgotten reemerge—the bear-shaman as avatar of ancient solar Buddha among them. The task of the poet, here, is to undergo the mildest of possessions, seized merely by such opportunities as pass to catch sight of and celebrate the self-renewing of archetypes across the unconscious poetry/prophecy of which our culture, often unbeknownst to us, is composed.

Ishiguro really is that lol

A fun exception to all this late style stuff, where you become more idiosyncratic or your work declines in quality or both, is Thomas Mann's unfinished The Confessions of Felix Krull: Impostor.

Mann decided to follow up Doktor Faustus by turning one of his most farcical early short stories into a novel, and the results are extremely silly, much more similar to Gentlemen Prefer Blondes than you'd expect from Mann.