A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I released “Words Failed Her” to The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. It’s one of the better (and longer!) recent episodes, a deep consideration of what makes Madame Bovary and the aesthetics of Flaubert so great and so troubling, so beautiful and so fraught an example to us all. (There’s even an intemperate aside, like the “incendiary footnotes” of these weekly posts, in the middle of the episode.) Please offer a paid subscription today to hear the whole thing, and to access the now 56-episode archive on topics spanning from Homer to Joyce and beyond.

My own novel Major Arcana arrives in almost exactly one month: it will be released on April 22. You can pre-order it here in print, ebook, and audio book formats (though the audio book will be released in two months, on May 20). There will also be a local release event here in Pittsburgh; it will be held at 7PM on April 17 at Riverstone Books in Squirrel Hill. The event is free: please register here! I should also have a New York date in May to announce soon.

For this week, what the hell, I’ll bite. Since Naomi gently chided me for demurring from the last round of men-in-fiction discourse, since I have nothing else to write about this week, and since I should also try to drum up a bit of controversy to sell my book, I’ll wade in, even if only to repeat myself (welcome, new subscribers!) and to end with another ad for my book. Please enjoy, if that is indeed the word!

Sit Down, Stand Up: Un-Vanishing the Novel

This week saw yet another flare-up of the “disappearing literary men” discourse, though more substantive and persuasive than usual, since the Compact article in question, Jacob Savage’s “The Vanishing White Male Writer,” both restricts its sociological evidence to literary fiction and focuses its aesthetic evaluation on the inadequacy of white male responses to the white male’s relative exclusion, from mainstream “woke” self-flagellation à la Ben Lerner to indie “based” bad-boy posturing à la Delicious Tacos.1 One is tempted to locate oneself in Savage’s chastening survey:

All those attacks on the “litbro,” the mockery of male literary ambition—exemplified by the sudden cultural banishment of David Foster Wallace—have had a powerfully chilling effect. Unwilling to portray themselves as victims (cringe, politically wrong), or as aggressors (toxic masculinity), unable to assume the authentic voices of others (appropriation), younger white men are no longer capable of describing the world around them. Instead they write genre, they write suffocatingly tight auto-fiction, they write fantastic and utterly terrible period pieces—anything to avoid grappling directly with the complicated nature of their own experience in contemporary America.

The chilling effect on literary ambition itself, which became coded circa 2015 in a vulgar Jezebel.com-type feminist variation on the postwar moral hypochondria, as a rape-and-genocide like design on the holy vulnerability of passive experience—this was real. It was even a real moral intuition, one you could make real art out of, as something like the novels of Henry James may prove, but in this form, as the discourse of a cadre of would-be professionals themselves ambitious but concealing their ambition beneath a mawkish rhetoric of “justice,” it was a secretly self-regarding and self-empowering form of adolescent moral lyricism.2

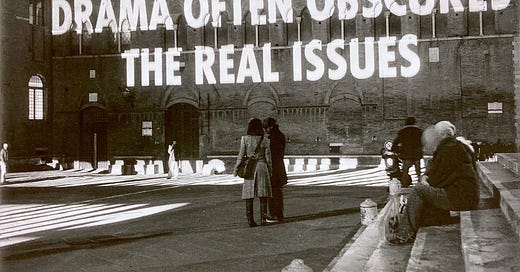

For proof both of the vulgarity and secret self-regard, and I mention it only because it’s a good example of something I discussed a few weeks ago, I was amused to see Wesley Yang and his (coarse, crude) readers dig these up. They don’t mention it, but the photos were taken at the first and only AWP I ever attended, 10 years ago next month in Minneapolis, around the time, in case you’re wondering, I decided to start self-publishing.

The above slogan remains the most telling one: the strange passive aggression3 of the message, a threat phrased as a guilt trip with its weird “concession” that only the white man has moral agency or any agency tout court, that it all comes down to his willingness to “sit down” even under the threat of—what? “Abolish” in this academo-social-justice sense, though it’s supposed to sound like it has something to do with slavery, is a much-degraded 10th-generation copy of Hegelian philosophy’s inscrutable Aufhebung, so it’s hard to say what a threat to “abolish” someone is actually a threat to do. And as it happens, the white man did not sit down—and a lot of non-white men even stood up. “My life is not an apology, but a life,” as America’s original litbro lectured the Romantic laity back in the 1840s. So here we find ourselves.

On the other hand, running back into the arms of David Foster Wallace and that model of the novel is likely not a solution either. I recently heard a right-wing YouTuber lament: “Modernity is divided between the autistic masculine and the hysterical feminine.” DFW and his anti-litbro critics perhaps embody these poles. The tragedy of 20th-century letters, our tragic legacy in this century, is that Ulysses is so staggeringly and breathtakingly great, that it is the achievement of a once-every-few-centuries talent, that it is probably, as Joyce Carol Oates once proposed, “the single greatest work of art in our tradition.” And yet, in all its flagrant cleverness and inorganicism and resentment, it is a dangerous model for the novelist or any artist. Faulkner and Woolf showed how the Joycean achievement could brought back within the Shakespearean remit of the novel—Shakespeare was the first novelist, Ulysses a critique of Shakespeare—but writing something long and illegible is not really a worthwhile goal in itself unless you are James Joyce, especially if you forget to hang it on a generally appreciated myth. One almost wishes Ulysses were a folly on the level of The Cantos or The Making of Americans, modernism’s great beached whales, books I’ve read enough of to know I don’t need to read the rest and neither do you. Finnegans Wake, after all, is also such a beached whale, though I’m sure I’ll read every “word” in it one of these days.4

When I wrote about this cursed topic before, I suggested that intellectual men had decamped from fiction to nonfiction, though even there you may be stigmatized as a “theory-bro,” and observed that realistic fiction had lost its cachet before the ideological turn of the 2010s, that the ideological turn was as much a cynical move of the money men and the powers that be to turn over to historically disempowered demographics an increasingly irrelevant industry because it was becoming irrelevant.

If we are serious in our belief that the realistic literary novel5 is an invaluable form of “sensuous thought” (Nabokov’s phrase) reflecting on and transfiguring the human experience, then we will have to invent a new version of this novel, one fully alive to the changes and challenges of the present, including the revision of gender roles accomplished by new technologies and new economies, at once the universalization and obsolescence of the autistic-masculine and hysterical-feminine, as attractive as these may be, with their comfortingly muffled wood-and-leather ring of the museal, tobacco-stained Freudian clinic, to sensibilities drawn to the old novel as to an old city.6

But we always reinvent old forms by summoning up prior models thought superannuated—it’s called juvenescence—as Pound and Eliot and Joyce “made it new” by leaping over the Romantics and realists back to the medievals, even though the Romantics had made the same medievalizing leap, in their case over the Enlightenment and its neoclassicism, itself a leap over the medieval and back to the antique. Who knows what antediluvian precursor ultra-modern Homer was transfiguring for his intransigent present day? And Harold Bloom, as we all know, and despite his reputation for masculinist rear-guardism, used to theorize that the deepest stratum of the Hebrew Bible was the work of a female modernist, Kafka’s sister, an ironic sophisticate of Solomon’s court deranging ancient folklore into high literature. There is no strategic advancement without tactical retreat.7

With all of the above (including my Joycean loyalties) in mind, I just ignored all of Savage’s strictures and, in Major Arcana, wrote a good old universalist panorama, serialized like Dickens, both crowd-pleasing and indifferent to any labels anyone might attach. (You don’t please a crowd by pleading with it, reasoning with it, or even looking at it. You just put on a show.) Major Arcana stars victimized women and aggressive men, and victimized men and aggressive women; at times the same men and women are at once victims and aggressors, because that’s what really happens in life, because life is not a comforting moral fable or an activistic political platform, and art must pay attention to this above all. Major Arcana avoids the gratuitously and tediously autobiographical, except for (appropriation alert!) something we might call my portrait of the artist as a nonbinary Zoomer girl, which need not necessarily concern you. Finally, Major Arcana is a (magical) realist metatext on the impulse to write or not to write “genre,” on the compromise and ambition and shame in which “genre” may involve the serious artist. Probably, you should read it, before we all, those of us still able to read, whether men or women or whatever, vanish.

I am too slow and impatient a reader to write these savage—or Savage—survey-of-the-literary-scene articles, though. For example, I’ve never finished a Ben Lerner novel, though I started all of them, and usually also flipped through the end, too. I did read his slim treatise The Hatred of Poetry, a popularizing digest of avant-garde presumptions about the need for an apophatic poetic, a poetic of poetry’s failure, i.e., the usual loathing of life and humanity exhibited by the 21st-century political left, or what Bruce Wagner recently labeled “ideological suicidal ideation,” an aping of Beckett’s hysterical-feminine defensive posture against the Joycean autistic-masculine plenitude, for politics is always a footnote to art, and none of us is capable of originality, and all radicalism is just a worn-out Parisian hand-me-down. The vanguardists, the progressives, especially never change; nothing is more stable and conservative, nothing more predictable and boring, than the avant-garde. I think of écriture féministe Carole Maso in an earlier moment of culture- and gender-war radicalism, the womanifesto for that Lispectorish experimental fiction of hers I could never get along with:

Wish: that straight white males reconsider the impulse to cover the entire world with their words, fill up every page, every surface, everywhere.

Thousand-page novels, tens and tens of vollmanns—I mean volumes.

Anyway, as I recall, Lerner argues climactically that Claudia Rankine is a better poet than Walt Whitman because the former’s focus on race evades the latter’s universalist arrogance. (Speaking of the professional managerial class’s will-to-power, that’s not all she evades, but never mind.) As our 46th president used to say: come on, man!

The original Red Scare podcast position. I am increasingly under fire for my qualified defense of this controversial text of our time, but I maintain that Anna K., even though I disagree with her about many topics, is about a billion times more truly ethical than her facile critics, because she thinks problems all the way through to their end rather than resting at the first merely moralistic slogan she stumbles across, usually just a propaganda-word of the last regime whose manifest failures brought us to the present pass. Consider her admittedly astringent reflection on the “unhoused,” a topic I think about a lot as a frequent user of public libraries. The old regime both did little to actually help these people—in fact, it just gave them a bare minimum of public services routed through a labyrinthine bureaucracy no one would want to deal with, not even people whose lives were going well—and then self-righteously accused everyone else of “cruelty” and “nihilism” or having a “suburban” sensibility for complaining that urban public space has (yes, I’m sorry, but it’s self-evidently true) been made physically (not emotionally) unsafe by their neglect. I think of this New Yorker article about the Minneapolis Central Library where I spent a lot of time writing and reading when I lived in that city. This library has been turned into a homeless shelter in all but name, one that puts a premium on not “judging” its users, though they may be in a state of fairly grievous disrepair. In my view, this “progressive” policy has ruined two good things. It has ruined true charity, since the city or county or state or nation has done little to assist these people who remain mired in literal filth, has only given them someplace to sleep during the day in uncomfortable chairs in a setting not designed for that purpose; and it has ruined public space and public learning by turning the library into a reeking, violence-prone combination of prison-yard, lazar house, and latrine. (Dark woke: “You don’t want a drug addict with scabies, a knife, and his dick hanging out to be in the children’s section of the public library? What are you, a fag, some kind of pussy or foid? Go back to the suburbs!”) Anna K. is capable of addressing such a quandary, even if in a more brutal style than I would adopt; her critics offer only moralistic blather. Revolutionaries always preferred harsh reactionary writers to sentimental liberal ones (Marx on Balzac, Trostky on Céline, Lukács on Scott) because at least the harsh reactionary can see the problem.

In our hardcore right-wing decade, though, aggressive aggression is back in style, even on the left. To wit, tough-guy literary sociologist Dan Sinykin goes “dark woke” and asserts it’s “pathetic” for white men to be “whining” they can’t be published. As a sometime acolyte of Nietzsche and Paglia, I can actually agree that bitching and moaning about one’s own debility and defeat is rarely “a good look,” but that’s hardly the historical position of the left-wing sociologist, who should at least be alert to nuance. This style of remark—“transphobes are faggots,” “misogynists are pussies,” etc.—seems to be the near-term aesthetic future of the left, as its Luigi-loving militant wing appears on the political level to be gearing up for a campaign of ’70s-style terrorism that’s going to get them all deported to a black hole in El Salvador. Meanwhile, David Rieff is assailed for showing an interest in the Compact article and thereby betraying his mother’s feminist legacy; she of course has no such legacy, was mostly interested in genius-level male writers, and also didn’t care to hear anyone whine about their exclusion—

She was a feminist, but she was often critical of her feminist sisters and of much of the rhetoric of feminism for being naïve, sentimental, and anti-intellectual. And she could be hostile to those who complained about being underrepresented in the arts or banned from the canon, ungently reminding them that the canon (or art, or genius, or talent, or literature) was not an equal opportunity employer.

She was a feminist who found most women wanting. (Sigrid Nunez, Sempre Susan)

—because, like several generations of intensely acculturated Euro-American midcentury intellectuals, including Arendt and Adorno and Steiner, she thought one had a sort of sentimental obligation to evince liberalism or leftism but was mainly concerned with high culture and could on occasion to be brought to a frank concession of its inescapable root in social inequality (unless, as Oscar Wilde hoped, we can get the robots to do the work for everybody). Someone else quips of the middlebrow Gen-X male novelists, in a reflection that the aesthetic rot set in before “wokeness,” “We’re left to read to old masters like Franzen and Chabon.” On the other hand, a tender regard for imaginative literature is not historically the position of the masculinist right either, certainly not in the Anglosphere, where realistic fiction was long the preserve of women and of men (Richardson, Dickens, Hawthorne) speaking to women and speaking as women, as some have also noticed in advocating for a revised right-wing and adventuresome masculinist canon for the novel. But irony in this matter, as in others, as I am always saying, never sleeps:

My earlier footnote citation of Carole Maso notwithstanding, this is not a subtweet of the literally voluminous William T. Vollmann, by the way, subject of this Metropolitan Review blockbuster by Alexander Sorondo. I read some of The Rainbow Stories in the year 2000—to impress a girl (!) who was into WTV—but went no farther in his oeuvre. A stay-at-home type, a preferrer of Hawthorne to Melville, of James to Twain, I’ve never been besotted with the experienced writers who ride the rails and go to war zones. Descending from those fairly recently immersed or embattled in the strenuous life, I tend to assume my ancestors, and some living family members who go in and out of jail, lived those lives for me and that all poverty and calamity are in any case about the same, less rich as artistic subject matter than their opposite. (Of course my true literary subject is the lower middle class: not so much its beauty as its aspiration to beauty.) The Lucky Star, which he’d wanted to call The Lesbian, a better title, sounds like the one I’d most enjoy, but please let me know in the comments.

Here are quite a few words from the old city; from the same part of the old city: kindness, generosity, tenderness; understanding, forgiveness; the novel. What if we can’t write novels without kindness? What if we have learned too well the Brechtian lesson about the “terrible temptation to kindness” and don’t even feel the temptation? I’m not going to answer these questions, and I want to resist the nostalgia that seems to be tugging at them, so let me bluntly say that I do not think kindness is the only virtue, or the greatest of virtues. If I have to choose among virtues, I have to say I prefer truthfulness, even if unkind. We need to see too that great unkindnesses were masked and made acceptable by the kindness of nineteenth-century novels.

Even so, kindness is a virtue, and we must miss it if it’s gone. And we do now seem to have a fuller answer to our riddle. When is a novel not a novel? When the streets of the city get too rough for kindness…

—Michael Wood, Children of Silence: On Contemporary Fiction (1998)

Brother Gasda issues some skepticism about the New Romanticism. I largely agree, with a few caveats. I think they were more like us, or us like them, than Matthew allows. Really, they invented us. (But didn’t Shakespeare invent us? Yes, but Romanticism is just Shakespeare systematized.) A lot of Romanticism was cultural commentary, mostly enabled by print: Hazlitt, Carlyle, Ruskin, Emerson, Fuller, and so forth. Emerson didn’t know he lived in the Romantic era; he called it “an age of criticism.” In other words, the Romantic era was an era of mass media and mass critique, just like today, rather than being entirely about the intensities of sex and suicide Matthew evokes. Romanticism invented the aesthetic sugaring of the modern pill, still visible in the “romanticize your life” social media movement. An inadequate solution, but better than nothing: Romanticism begins when the revolution fails, which is why nothing is more Romantic than being a revolutionary when you’re young and a reactionary when you’re old. (They invented that too, as Matthew points out, along with hoping you die before you get old.) And the sex and suicide are still with us. Mary Shelley finding out that any relationship with Percy was just going to be a “situationship” in his eventually inexistent long run—is this, which is happening in every city in America as we speak, sometimes with the genders reversed, worth eulogizing as such? Is Byron’s death “for” Greece really any nobler, except that he put his proverbial money where his mouth was, than the bathetic surrogate nationalisms the deracinated and exsanguinated American intellectual now feels for Ukraine or Palestine? (As elegy for and reliquary of Romanticism, for and of Byron and Shelley, I can’t recommend Mary Shelley’s The Last Man more highly. Why isn’t everybody talking about this book all the time?) To the extent that I ever called for a New Romanticism, I meant it as a call not to complete the critique of industrial society but simply (as stated in the post above) for a less embarrassed and more vital literature, for a renewed faith in the power of individual imagination to allow us to live in this society, as Keats (my favorite Romantic) wrote in a selfish spirit of Mammon-worship to the more moralizing (and therefore predictably less moral) Shelley:

I received a copy of [Shelley’s play] the Cenci, as from yourself, from Hunt. There is only one part of it I am judge of—the poetry and dramatic effect, which by many spirits nowadays is considered the Mammon. A modern work, it is said, must have a purpose, which may be the God. An artist must serve Mammon; he must have “self-concentration”—selfishness, perhaps. You, I am sure, will forgive me for sincerely remarking that you might curb your magnanimity, and be more of an artist, and load every rift of your subject with ore.

Lol "the reason i'm not writing the intros to sontag reissues is bc her son is a chud"... really, that's the ONLY reason?

Yes, do keep us posted about NYC or other northeastern events! I think there’s something of what Freud said about Dostoevsky to someone like Anna K: it’s disappointing somehow ( this disappointment has somehow outlived my own commitment to the sort of leftism she pretended) to see an examining mind come full circle to parochial prejudices (wanting good things for one’s community first is one thing, but there is a particular form of it that feels very connected to the race realism she’s engaged in and the suburban sense that there are barbarians at the gates.) Freud was wrong about Dostoevsky of course, but has Anna K written a Sisters Karamazov or an Underground Woman? Agreed that she needs a project. I have very mixed feelings about the library as community center phenomenon myself, but I think it’s first and foremost downstream of the decline in public literacy.