A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I posted “Such Strange Lives Are Led in America” to The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. This episode concerns The Bostonians, Henry James’s 1886 masterpiece of the ever-present American culture war: a novel about the rivalry between a Southern reactionary straight man with a Northern radical lesbian for the affections of a preternaturally gifted ingénue and magician’s beautiful daughter. Everything that characterizes the “now,” from Carlyle-inspired neoreactionary belletrists to occult revivalists to a political left fractured on lines of class and sexuality, also characterizes The Bostonians. The renunciation of partisan action in the name of an expansive aesthetic consciousness, James implies, is all that will save such a fractiously imperiled national union. We may not agree with this belatedly Romantic advice—it was as belated in 1886 as it is now, which is why James had to guise it in ironical literary realism—but we should at least weight it in the balance with the more fashionable calls on right, left, and center both to action and to faction. Please offer a paid subscription so you can hear the whole episode; you will also be able to access the burgeoning archive of episodes on modern British literature from Blake to Beckett, the works of James Joyce with a focus on Ulysses, George Eliot’s Middlemarch, and American literature beginning with Emerson. Thanks to my current paid subscribers for making this project possible!

(I also announce here that I’m adjusting the schedule for the next few weeks of The Invisible College. We will rejoin poetry with Robert Frost next week, as promised. After that, though, I’m moving Hemingway and Fitzgerald forward and Pound back. I want more time to research the recondite Pound, and I’d also like to juxtapose him directly with Stevens following my Substack post from this summer. So the Frost episode on 11/08, Hemingway on 11/15, Fitzgerald on 11/29, and Pound on 12/06.)

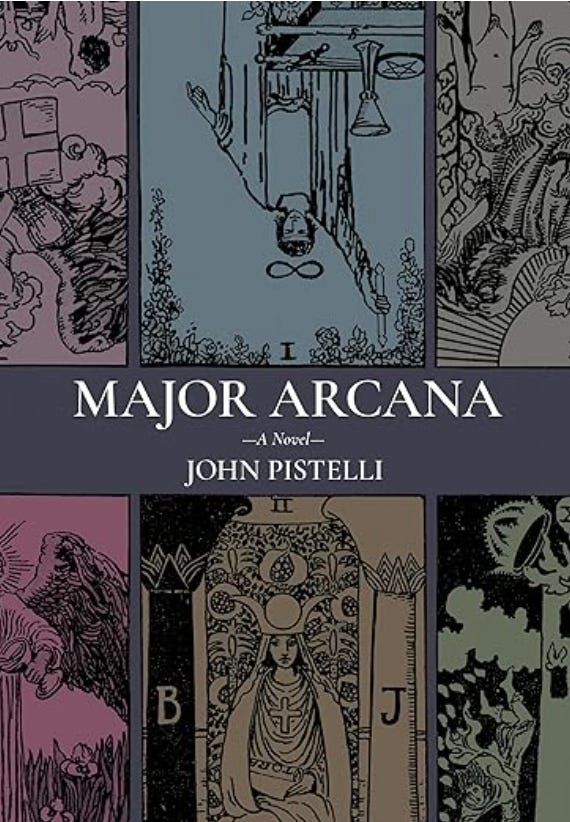

I also gently remind you that Major Arcana, my own novel of American culture war and occult revival, is forthcoming in a beautiful paperback edition from Belt Publishing that will be released in April 2022. You can pre-order it here, get it from NetGalley here, and access the original Substack serial (including my audio rendition) as a paid subscriber here.

For today, a recapitulation of themes long prominent in this Substack raised to a volume I hope is loud enough to be heard over the agitations of the coming week. Nothing I haven’t said before—we writers of weekly newsletters do repeat ourselves—but nothing new readers couldn’t stand to hear for the first time, and nothing long-time readers couldn’t stand to hear again either. (When you people start taking this advice, I’ll stop dispensing it!) Thanks for reading, and please enjoy!

Against the Endless Empire: The Poets’ Politics

When did fascism end? When did it begin? Do we live under fascism now? Will we begin living under fascism in three months? In his hopeful contribution to the perennial “is Trump a fascist?” question, friend-of-the-blog Ross Barkan reminds us that Kamala Harris’s ally Dick Cheney is perhaps the American fascist par excellence, never to be outdone:

Trump will never match the breadth and terror of the Bush regime—such a novelistic twist that the Cheneys are behind Kamala Harris now. If American fascism had a face—and even he, grimacing and grunting, couldn’t entirely subdue this country—it was Dick Cheney’s, and it is difficult for the young to understand what he was able to accomplish in a few short years. Vice President Cheney was the architect of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the open-ended invasions that immolated the Middle East. He was the architect of the modern surveillance state and the torture facilities of Guantanamo. Does Trump have another Patriot Act in him? Likely not—he lacks that sinister ambition, and the people around him do not resemble Bush’s neoconservatives, the Rumsfelds and Wolfowitzes who marinated in government for decades before finally getting their chance to wreak havoc in the shadow of the most cataclysmic and surreal terrorist attack in modern history. A month after the September 11th attacks, George W. Bush had an approval rating of 92 percent. That is the kind of world-historical popularity required, at the outset, for fascism—only with such an eruption of good will can American institutions be ground into dust. And Bush got as close as any president would. He didn’t have to deny elections because he won them, beating John Kerry in the Electoral College and popular vote, and he left behind the surveillance machinery that no president, Democrat or Republican, has ever attempted to dismantle. Bush created the Department of Homeland Security. He metastasized the CIA, FBI, and NSA. Once, it was liberals railing against this so-called deep state. Now the right-wing does it, and they may have a point. What hope does their man, Trump, really have against any of the three? What hope against the Pentagon? Even if he were magically gifted with Xi’s pharaonic will, Trump could not overwhelm them.

And yet Ross expresses nostalgia later in the essay for a can-do midcentury America able to build ambitious things. Such nostalgia recalls the libertarian argument that precisely this America was the true fascist state, that FDR was nothing less than the American Mussolini. Leftists and libertarians have completely different definitions of fascism, ones they conveniently apply to each other. Conservatives and liberals have still other definitions of fascism; these, too, mutually apply. Trump has called Harris a fascist. From within the coherent worldview of his movement, she is. But re-assembling for oneself the coherent worldview of others from a departure-point of tactical sympathy and in the interests of holistic understanding—this is a lost art in today’s America.

Fascism, we might speculate, does not currently exist and has not existed since the end of World War II, but is merely the abjected and projective “other” of every contending faction in a the postwar international order, the glue that holds the system together, like the barbarians in Cavafy’s famous poem. We are all fascists all the time; none of us ever are.

I myself am not a young man any more. I distinctly recall furnishing historical proofs on Livejournal of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney’s inarguable fascism in advance of the 2004 election. One can only live through so many of these cycles before one realizes that, as Bruce Wagner likes to say when he’s not saying how good my novel is, it’s all an illusion.

I want to make a slightly different point from that metaphysical one, however. I want to make (again!) an argument about the appropriate political disposition of the artist. Neither the political actor nor the political philosopher can quite agree about fascism, but when do artists think fascism begins and ends? If fascism in its mythic dimension is nothing less than the enslavement of the human being to the brute calculus of organized society, then it has indeed begun everywhere and ended nowhere.

Trump and Cheney are fascists? Compare to what, ask our writers? As I’ve had cause to mention before, two writers as different as Gore Vidal and Thomas Pynchon essentially believed the Nazis won the war, that the American republic declined to a fascist empire sometime around 1947 with the full founding of the deep state. Their contemporary Toni Morrison, however, signals with Beloved’s dedication (“Sixty million and more”) the likeness of the slave trade to the Holocaust, thus dating New World fascism to the middle of the last millennium. In her account, this fascism ends not with abolition or with the false promise of the Civil Rights movement but is perpetuated in the present (Sula: “Things were so much better in 1965. Or so it seemed”) through a de-humanizing and universalized technocracy she seems to find cognate with the rational management of the plantation.1 Melville goes much further than Morrison with the gnostic suggestion (“the old State-secret”) in Moby-Dick that fascism begins with the reign of orthodox monotheism’s God who has dispossessed mankind of our rightful sovereignty. We are, he says, the scattered progeny of a captive king, presumably the Kabbalists’ Adam Kadmon. William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley thought much the same, the latter with recourse to Classical rather than Biblical precedent in the form of Prometheus. Blake, Shelley, and Melville, you will say, were mad heretics, yet all three read cosmic history2 through the telescopic lens of their pious precursor Milton; he taught them in the first place to read the Bible black where the priests read white. Perhaps Catholic Dante can provide us with a more comforting orthodoxy than these deranged Protestants? Not quite. While the poet seems to learn on his journey that human art should humbly and faithfully copy God’s divine handiwork, the poem itself audaciously identifies its own all-encompassing wholeness with the creation and improves upon rational theology with its Troubadour enthronement of the poet’s beloved. For Dante, too, fascism is the cosmos in its resting state, poetry per se the agitated resistance—the recreation of the creation as it should be. Dante seems to condemn Homer’s Odysseus for going too far but actually condemns him for not going far enough. Dante dramatizes what Hegel and Goethe will later theorize as the practice of Romanticism: God requires the devil—in the form, among other forms, of poets writing wicked books—to revise, correct, and improve him, to liberate the human mind made in his image from his fearful curtailment of that image’s own world-making power. Sans such dialectical deviltry, fascism reigns over us as it reigned over the primal chaos and rained down on the cities of the plain. And as for Homer himself, what does he depict—did not Sister Simone teach us to read him this way?—but the rule of fascism as the sovereignty of force over human affairs, redeemed only by sympathetic knowledge and the actions of grace? Philip K. Dick gives us an epigram summing up the whole crypto-gnostic wisdom of our literary tradition in its war against the false god in the name of the true, or rather in god’s war against himself to liberate his mind from his mind’s bondage: “The empire never ended.”

I move, too quickly, through these examples, and I could multiply them—Euripides, Ovid, Shakespeare, Dickinson, Joyce, Woolf—to demonstrate only that poets’ time is not best spent in telling people how to vote in any given election or to writing elaborations on their (our) pet political theories.3 Our vocation, if we heed our precursors, demands more of us than that, nothing less than a standing challenge to power as such,4 and, if we compare our own positions to those of Homer or of Dante, then there is, if not exactly a right side of history, still some reason for optimism that the brain remains wider than the sky. What better to quote in conclusion, then, than the most rhapsodically optimistic passage ever written by that most incorrigible of optimists, the mind of America, Ralph Waldo Emerson?

The expansive nature of truth comes to our succor, elastic, not to be surrounded. Man helps himself by larger generalizations. The lesson of life is practically to generalize; to believe what the years and the centuries say, against the hours; to resist the usurpation of particulars; to penetrate to their catholic sense. Things seem to say one thing, and say the reverse. The appearance is immoral; the result is moral. Things seem to tend downward, to justify despondency, to promote rogues, to defeat the just; and by knaves as by martyrs the just cause is carried forward. Although knaves win in every political struggle, although society seems to be delivered over from the hands of one set of criminals into the hands of another set of criminals, as fast as the government is changed, and the march of civilization is a train of felonies,—yet, general ends are somehow answered. We see, now, events forced on which seem to retard or retrograde the civility of ages. But the world-spirit is a good swimmer, and storms and waves cannot drown him. He snaps his finger at laws: and so, throughout history, heaven seems to affect low and poor means. Through the years and the centuries, through evil agents, through toys and atoms, a great and beneficent tendency irresistibly streams.

This controversial analysis—the Morrison of Sula seems almost to dislike electric light, as Lawrence before her despised indoor heating—echoes that of some political philosophers. I think of Giorgio Agamben, with his theory that the Nazi concentration camp is the paradigm of all modern governance. The cognoscenti celebrated him when he applied this theory to the War on Terror, execrated him when he applied it to the global response to the pandemic, and yet it was the same theory in both cases, and, in the event, proved more or less correct in both cases. He borrowed his theory somewhat from Hannah Arendt. In The Origins of Totalitarianism, she argued in essence that fascism is always already implied by liberalism’s founding secularity, its Hobbesian reduction of man to rationalizable animal. Events like the Holocaust, the War on Terror, and the pandemic response—events where a totalizing bureaucracy reduces the human being to a number so that some number of human beings can be disposed of—will recur unless we re-establish the agency of the human being as infinite subject of the world rather than its calculable object. A recent, timely, and welcome polemic from the left against political polling is very much in Agamben’s and Arendt’s spirit, even if its writer might object to some of the former’s political interventions of this difficult decade.

Speaking of cosmic history: last week I spent a footnote complaining that astrology is no better able to predict the results of a presidential election than is the pseudo-science of polling. Astrology, I suggested from my entirely amateur position, might better be regarded as a qualitative art of creative interpretation than a quantitative science of rational measurement. Friend-of-the-blog Emmalea Russo accordingly demonstrates this creative art in her own brilliant astrological reading of the election:

To read Trump as either “savior” or “Hitler,” angel or demon, divider or uniter, is to neglect the intriguing and ambiguous energy of Mercury, which, in its alchemical role, divides and unites. But then again, Mercury is famously deranging (cc: Trump Derangement Syndrome) and so it is easier to pedestal or diss him than to study him from a distance.

“Okay,” you might say, “but who’s going to win the election?” I don’t know. In 2016, I said Trump would win in a since-deleted post on my then-blog that made the rounds on Twitter. In 2020, I said, but only privately, that it would be closer than prevalent polling anticipated. But this time, “both sides” are so insulated in their own private worlds of numerical rhetoric, each predicting its own landslide, that there’s not even any conventional wisdom to agree or contend with. The only conventional wisdom seems to be that “it’s going to be close.” I would like, then, as an incorrigible contrarian, to suggest that it might not actually be that close, that it will decisively break one way or the other, even if I am not quite prepared to say which way. (I offer one meaninglessly anecdotal “data-point”: most of the swing-state pro-choice middle-class suburban white women I know—and I know more than you might think, given the class of my origin—are voting for Trump. They are pro-choice in principle but in practice are more afraid of what further Democratic rule portends for the economy. Their pro-choice principle, for that matter, is not the same as the left-wing intelligentsia’s, or at least I don’t think it is. On the occasion of the Dobbs decision, I overheard one of them say, “They can’t outlaw abortion. Who’s going to pay for all those black babies?” The mind reels. I refer you again for aesthetic remediation of this hideous comment to the novels of Toni Morrison, and for philosophical remediation to Hannah Arendt’s treatise; I warn you again—see here—that the supposed moral high ground of the center left is in fact the ethical bog of Fabian socialism.) Anyway, the coconut contingent now think they’re going to take Iowa and Ohio with the rest of the Rust Belt on a wave of women furious at the end of Roe; MAGA is convinced its multiracial coalition of angry working-class men will sweep the Sun Belt so thoroughly that it won’t even need the Rust Belt, reclaiming Nevada at one end and Virginia at the other. Each has their preferred polls supporting their delirious or delusive optimism. (I think polling, like psychology and sociology, should be banned.) Either outcome would represent a satisfying comeuppance for the contenders in the eye of those of us who appreciate irony in the abstract. What if Trump loses his original white working-class constituency, and thus loses a second election, because of the Faustian pact he made with a religious right he otherwise disdains? And what if Harris, after having merged ideologically with Dick Cheney, after running for George W. Bush’s third term, loses with an electoral map that looks like John Kerry’s? (The latter outcome would be in keeping with the nagging sensation I’ve described several times this year that we are reliving a demented version of the 2004 election.) Other than this reminder that irony never sleeps, and that the unpredictable could always happen, I make no prediction. As for my own preference, it is, to quote Don DeLillo’s reply to the same question, none of your fucking business—and neither side, in any case, accords with my own poet’s politics. Our quadrennial carnival of democracy is not for the faint of heart. Stay safe out there.

That it may demand too much, so much that we will become fascists and totalitarians in our turn, is the wise caution offered by the Camus of The Rebel, for whom our basic human desire to kill God too easily gives way to our desire to replace him and build a church of our own. Thus he condemns the aesthete followers of Nietzsche no less than the activist followers of Hegel for erecting the totalitarian world of the midcentury in which he wrote his chastening prose. It is a warning we should heed. One way to heed it is not to harden our fluid aesthetic dreams and longings into an iron political doctrine. The true artist, Camus seems to say, belongs to the cosmic political left but will for that very reason often have to oppose the mundane political left, since the mundane political left balefully transforms the legitimate yearning of the cosmic political left into only more prison bars for the soul down here on earth. The essence of literature is irony, which the mundane political left prefers to outlaw, for this very reason. Irony reminds us that no accomplished fact, not even any given artwork no matter how brilliant, could ever be commensurate to the totality of truth and thus spurs us ever onward to further and higher truths. That both Hegel and Goethe identify irony with the feminine is, as academics like to say in their footnotes, beyond the scope of the present argument, but it is a persistent object of inquiry in my novels.

FDR, of course, did the most fascistic thing of all - intern the Japanese.

An interesting bunch of thoughts. I think, without quite disagreeing with Pynchon & Vidal (he calls it “communism” rather than “fascism”, but Kojève’s famous line about the equivalency of the midcentury US and USSR hits on something similar) I would perhaps throw my lot in more with James Joyce contra Morrison and Lawrence. Not exactly in favor of empire, but extremely wary of what replaces it, the parochialism, the drive to purify the body of the nation, to remove the elements “poisoning the blood” as it were. That said I agree about the artist’s duty to try to imagine something else, however hopelessly.