A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

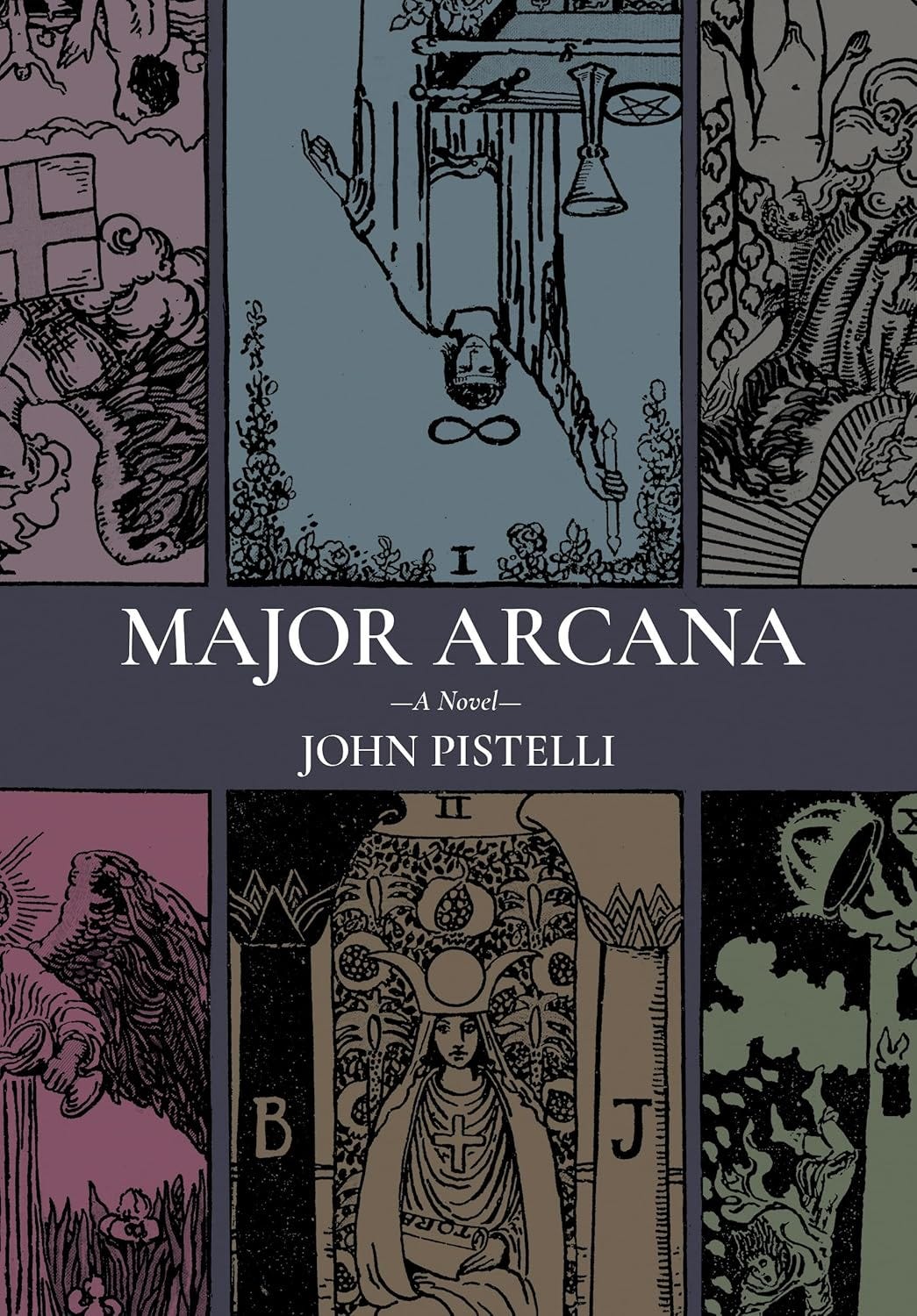

Above is the cover of the forthcoming Belt Publishing edition of my new novel, Major Arcana. Scheduled for release on April 22, 2025—the day before Shakespeare’s birthday—it can and should be pre-ordered here. Pre-orders, as you may know, are the coin of the realm in publishing; pre-orders of Major Arcana will therefore encourage all publishers by example to be as adventurous as Belt has been.

For my new readers wondering what Major Arcana is all about, please see a comprehensive spoiler-free review by Mary Jane Eyre here (“Pistelli’s own attempt at a Q.E.D. of the proposition that…one can write imaginatively about the present”) and a brief review by and long conversation with Ross Barkan here (“perhaps the elusive great American novel for the 21st century”). The first edition, independently published, garnered three additional Goodreads reviews in its brief shelf life, all positive, which can be read here.

Major Arcana was first serialized on Substack, and is in fact the first Substack-serialized novel to garner a book deal. Paid subscribers can still access this version, with my accompanying audio rendition of the text.1

The ongoing project for paid subscribers here at Grand Hotel Abyss, however, is The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. So far I have created 27 lectures of two hours or more on modern British literature from Blake to Beckett and on the works of James Joyce. This week we took a well-earned summer vacation after what is simultaneously the most disturbing and the most psychedelic reading of Ulysses anyone has ever encountered.2 We will spend the month of August further relaxing our nerves with that epic of moderation, George Eliot’s Middlemarch, before turning in the fall to the derangements of classic American literature from “Self-Reliance” through The Sound and the Fury.3 The first episode on Middlemarch, scheduled for release on Friday, will be free to all.

For today, I continue my summer vacation by pulling something up out of my archive for its resonances in the present day. In the present day, the aforementioned Ross Barkan wrote a polemic called “The War on Genius,” with which I agree. I mostly tried to ignore the subsequent social-media controversy, though the whole question of genius follows from a prior discussion of a potential “New Romanticism.” I recently remembered that I wrote a brief essay 11 years ago that will be of historical interest to Invisible College listeners and that ends with an explicit call for such a New Romanticism.4 I repost it below with the usual added footnotes, though you really should skip them this week. Please enjoy!

Peregrinations of Beauty: Modernist Fiction as Romantic Poetry

[Originally published to johnpistelli.com on September 13, 2013.]

A literary-historical question: Did the modernist revolution in literature have opposite consequences for fiction and poetry when it comes to beauty?

The modernist poet-theorists, after all, derogated both ornament and emotion. Pound redefined beauty in medieval and neoclassical terms as “fitness to purpose” and eulogized rough, edgy Browning among the Victorians, whereas melodious Tennyson was the favorite Victorian whipping-boy of the modernists. Eliot and Pound had harsh words for Shakespeare (Pound preferred Chaucer; Eliot pronounced Hamlet an artistic failure), along with Milton, the Romantics, and their 19th-century successors (the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetes). Pound and Eliot elevated instead colder, more organized, and more conceptual figures from the western tradition: Dante5 and Donne most famously. Forget the messy subjectivism and musical passion of the Romantics (including the proto- and the post-) from Shakespeare to Wilde, they counseled—the modernist watchword in poetry is Classicism.

But the modernist novelists present a different picture. Woolf revered Shakespeare, Shelley, and Pater; Fitzgerald was legendary for his love of Keats; Faulkner read (baggy, subjectivist, proto-Romantic) Don Quixote once a year; Lawrence looked to the American Romantics and Forster to the German; and Nabokov, of course, had Pushkin.

Even the more severe Joyce and Beckett never shook their youthful Shelleyan influence. Joyce’s two least attractive features may derive from Dante—the excessive systematizing and the vindictive obsession with local politics—but he allowed that he would take Shakespeare over Dante to the proverbial desert island. (Even here, though, the renegade Irish Catholic couldn’t resist a Swiftian barb against the capitalist Bard of the empire: “the Englishman is richer,” he mischievously explained of Shakespeare’s superiority to Dante.)

Accordingly, isn’t it the case that fictional prose becomes conspicuously beautiful as its focus moved inward in the 20th century? By “beautiful,” I mean deliberately rhythmic and patterned, full of sound devices like alliteration, consonance, assonance, and various forms of pleasing repetition, as well as marked by holistic imaginative devices like metaphor and simile. Modernist poetry, on the other hand, goes in the opposite direction, toward the austerities pioneered by Imagism or the rigorously anti-affective maneuvers of the avant-garde, which latter continues into the present in such schools as Flarf and conceptual poetry. Are there any passages of 19th-century fictional prose as beloved for their sheer linguistic beauty as the conclusions to “The Dead” or The Great Gatsby or The Unnameable, the “Time Passes” section of To the Lighthouse, the opening of Humbert’s narration in Lolita? This trend continues to the end of the 20th century, in the work of older writers at least: read just the final paragraphs of Don DeLillo’s Underworld and Toni Morrison’s Paradise for prose-poetry comparable to the best of the 1920s.

Earlier fictional prose was not so concerned with beauty; if language-conscious, I would suspect it tended toward the suasive gestures of rhetoric rather than any sort of lyricism, as when Dickens exhorts the reader or George Eliot ventures philosophy. The major exceptions that leap to mind—Melville with his Shakespearean and Miltonic thunder that anticipates Faulkner and his successors; Flaubert with his precise imagery and flowing sentences that inspired writers as varied as Joyce and Cather, Hemingway and Nabokov—were more valued in the 20th century than in their own time.

We can further say that modernist novelists were in a role analogous to the Romantic poets themselves in the history of their respective art forms. That is, as the Romantics rebelled against the Enlightenment period of Newton’s sleep and Voltaire’s mockery by sweeping the overly social, overly satirical, and overly objective out of poetry to clear a space for emotion and metaphysics and lyricism, so too did the modernists confront the “materialism” (as Woolf called it) of late-Victorian and Edwardian naturalists, who, like Enlightenment figures before them, were too narrowly focused on society as such and too naively hopeful about rational solutions. Rather than looking to Dante and Donne to re-animate Classicism with those modernist poets who were revolting precisely against Romanticism, the modernist novelists followed Shakespeare and Keats in combining psychology with lyricism, in setting subjectivity to prose music: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Mrs Dalloway, The Sound and the Fury.

I should avoid any comparison with our own period, but, if you’ll permit me to generalize, it seems to me that we’re in a rationalist and satirical cultural desert, choked by glib sarcasm, ephemeral political commentary, and mindless technocracy.6 Much of our fiction and criticism shows the damage: it’s overly rhetorical, “funny” in a forced way, militantly anti-metaphysical, and boringly sociological. Some kind of neo-Romanticism is in order, and will, I think, arrive in due course. History is not teleological, as both progressivists and declinists like to believe, but cyclical.

The Substack version, the self-published edition, and the Belt edition are substantially the same—no changes of plot, structure, or characterization were made—but each edition is of a successively higher prose polish and concision. Future scholars will no doubt enjoy their task of inferring vast thematic consequences from the minor edits between versions. I’ll even give one up to the sociologist of literature: I took out a short paragraph gently satirizing BookTube for the Belt edition since I figured there was no point in gratuitously insulting what is now a target audience. Score one for Pierre Bourdieu! And yet my vast structure still stands.

A schematic summary can’t reproduce the intensity of the recordings, but here’s a hint: James Joyce is God, Stephen Dedalus is his prophet, Leopold Bloom is his messiah, and Molly Bloom is his submissive creature guised as the goddess of earth. Not only that, but Ulysses is the hidden Bible of the secret theocracy we now live in. See? Disturbing and psychedelic!

Reminder for regular readers and FYI for new ones: I don’t love paywalls and feel I have earned the right to one only due to the almost decade’s worth of free content you can find on my website and my YouTube channel, the latter of which contains over 60 lectures on modern and contemporary American literature with a preponderant emphasis on diversity, thus the old-style canonicity of my selections for The Invisible College. If any of the VCs prowling around Substack in quest of the new culture wants to drop a million or two into my bank account—a big movie/TV option for Major Arcana would also work; I’ll write the script if you want—then I will happily give away everything but the print books. For now, though, I need the money and you need the entertainment, so please offer a paid subscription.

Our most intriguing denouncer of Romanticisms new and old just signed a book deal, too, for a novel that sounds like just the kind of imaginative narrative I advocate and a treatise I’d like to have read before I wrote Major Arcana:

Original footnote: Dante, too large a figure to be captured by these categories, is obviously susceptible to both Classical and Romantic interpretation. In general, the Classicist would emphasize his imagistic objectivity, pattern-making intelligence, and conceptual order, while the Romantic would praise his visionary intensity, his musical terza rima, and the passion of his poetic personae. See Wilde’s The Critic as Artist for a Romantic Dante. (Since writing this, I have become aware of the esoteric interpretation of Dante as gnostic goddess-worshiping Troubadour, which furthers my understanding of the poet as a proto-Romantic figure—and perhaps of the modernist poets’ interest in him as a cryptic revelation of their own latent Romantic tendencies.)

That was 2013. Has this description of the mainstream aged well or poorly? “You’re trying to sell books,” I tell myself. “Just don’t write about politics, for Christ’s sake—you’ll only get in trouble.” Don DeLillo, in a 2007 interview with Die Zeit, even gave us a script:

ZEIT. What is your political orientation?

DD. I am independent. And I would rather not say anything more about it.

ZEIT. Why not?

DD. Well, in the Bronx where I grew up we’d have put it his way: Because it’s none of your fucking business.

ZEIT. For readers of this conversation, we must here add that you are laughing.

But I am forced to observe the following. The identity politics that swallowed mainstream American or Anglophone literature whole after 2013 was the main weapon in the war on genius. I subscribe to the Romantic definition of genius according to which the term refers not to the brilliant artist as a person, as if the artist’s achievement had something to do with a supposedly innate quality like I.Q., but to the world-spirits—or, as Alice Gribbin would put it, the Muses—attendant upon artists who make themselves open to such spiritual influence. According to identity politics, on the other hand, artists make art only out of narrow social experience; their art is only valuable for reflecting this narrow social experience to a histrionically “enlightened” and semi-compassionate bourgeois readership. By definition, any higher conception of art, a conception that elevates both artist and audience above the merely social, is barred. The counterculture reaction against this left-identitarian takeover of the middlebrow didn’t always rise to the challenge—sometimes it merely put an even more contemptible right-identitarianism in its place, as with Red Scare’s Steve Sailer fixation—but I was becoming cautiously optimistic that an emergent New Romanticism really would break the yoke of identity and remind us of art’s power to liberate the imagination from the merely given.

This past week’s rather strained astro-turf campaign on behalf of Kamala Harris’s not especially democratic elevation to potential president, however, was like the scene in the horror movie where the apparently slain Jason or Freddie roars back to life. A week of wall-to-wall 2010s-style poptimism redivivus culminated in the full re-emergence of the true fascist style in American politics: an imperial state managerialism of racial subgroups, part of what Arendt meant by totalitarianism, which ought, almost, to be illegal. The war on genius, which is a war on the very idea of humanity as world-making historical agent, looks like many things, but it also looks like this, stupid as this happens to look:

If Harris were politically savvy, she would improve her still-weak position in the polls by Sister Souljah-ing this ideology in the strongest possible terms, but I fear our current politics are too brittle for its protagonists to accomplish any such maneuver. Maybe I will be pleasantly surprised. One imagines how Obama in his prime would have handled it; I can almost hear him thundering that we’re all Americans first and foremost. Even Trump, no doubt opportunistically, denounced the “extreme right”—he meant Christian cultural conservatives—from his rally stage last weekend. (I’m not asking politicians to forego opportunism. I’m asking them to be opportunistic in deference to humane values.) But then Trump is “woke” too now, to complete a trifecta of Ross Barkan links in this post, and “woke” and identity politics are not quite the same thing, nor is “woke,” at least insofar as it’s synonymous with anti-essentialism, always all bad. As I argued here, an argument hinging on an esoteric interpretation of Dante, Harold Bloom’s much-derided polemics against the intellectual left essentially accuse them of being “not woke enough.” I’m sure you thought my semi-woke apologia for Trump’s heterogeneous persona two weeks ago was a stretch, but look where we are now.

The Democrats in their seemingly now-exclusive pursuit of the mean-girl vote (“You’re um like [twirls hair] sooooo [cracks gum] weird”) are about two days from Donald Trump Is a Fag. Did they all re-watch Heathers to memorialize Shannen Doherty and forget in their grief that she’d played the movie’s villain? It will be interesting to see if this proves effective messaging. I find it off-putting—it makes me want to buy a MAGA hat, to fling some flagrant bizarrerie into the smug face of bourgeois complacence—but then I’ve always been, you guessed it, weird. Why does such a political style have this effect on me? A persistent problem addressed in my work—my critical work, but my creative work even more so—is the problem that all counterculture in the west for the last two centuries, and thus everything that looks like artistic and political progress in the west for the last two centuries, has been conducted against the imago of white middle-class domestic woman. You can point to whatever material realities you like, but imaginatively we have not lived in a patriarchy since the Renaissance; the first story about what it feels like not to live in a patriarchy—it feels like you’re wondrously free and also like you’re going crazy—is Hamlet.

Well and good, you might say if you are on the left and hate whites and the middle class; well and good, you might say if you are on the right and hate women and the middle class. But the fearful symmetry in the statement identifying the feminine with class-and-race domination explains why this burning of the domestic witch poses a problem rather than solving one. When you add the fact that art’s sequestration from public life mirrors women’s equivalent isolation in the domestic sphere, categories still subtly but crushingly operative in and through the very feminism that was supposed to dissolve them, then you have a philosophical conundrum to last a lifetime. In literature, this is a problem of genre before anything else—poetry (representing both revolution and counter-revolution) vs. the novel (representing the settled order of liberal modernity)—as Paul Franz suggests in a recent essay, with usefully cross-gendered exempla, domineering father Milton standing for the domestic-novelistic, rebellious daughter Plath for the revolutionary/reactionary-poetic:

Samuel Johnson, in his Life of Milton, observes that for no author prior to Milton has there been kept a detailed record of his place of living. Johnson proceeds, therefore, over the course of his narration, rather dutifully—which, given his distaste for all that smacks of “enthusiasm,” is also to say rather mischievously—to record the various places where Milton lived. For comment on this, we may turn to a writer who once expressed affront at the very idea of the 18th century. “Poetry, I feel, is a more tyrannical discipline,” Sylvia Plath responded, when asked by an interviewer about the relation between her two genres, “you’ve got to go so far so fast in such a small space that you’ve just got to burn away all the peripherals—and I miss them. I’m a woman, I like my little lares and penates, I like trivia, and I find that in a novel I can get more of life, perhaps not such intense life, but certainly more of life.” Burning away the peripherals, the modern poet, who as like as not begins as a kind of lar, or household god, burns down the childhood home.

Whether my own work moves us any closer to a solution is for my readers to judge. I hope that Major Arcana marks an advance when its narrative leaves domestic woman as the last artist standing and turns the satanic-gnostic daughter-rebel into the novel’s final avatar of maternity. But a political solution will follow from an artistic one and not the other way around. The world must be reimagined before it can be changed. Artists, therefore, and I include myself, are well-advised that mere political commentary is wasted breath, no matter how many “most important elections of our lifetime” go by. (My younger readers may or may not be comforted to learn that any victorious Republican will be called Hitler in the moment and then recalled later even by liberals as a great and distinguished statesman.)

If we’re being honest, most of us, even if we’ve read the Divine Comedy, can’t recall without a quick resort to Wikipedia whether Dante was a Guelph or a Ghibelline, though this meant life or death to our exilic poet. Might this suggest how much it will matter, if anyone is remembered from our era, whether one was a Democrat or a Republican? Everyone in a given epoch looks the same to the eye of the future, anyway, as we know from laughing over bygone fashions in old photographs; we will be remarkable, as C. S. Lewis observed in a related context, only for the assumptions we didn’t even know we shared across our loudly advertised differences.

I think of Emerson the Boston Brahmin railing against the coarse, bigoted populist Andrew Jackson in his journals, like any MSNBC-watcher today foaming against MAGA; our Transcendentalist prophet thought his “self-reliance” was the exact opposite of the coming mobocracy Jackson portended; and yet Emerson has sometimes been set down in cultural history as the laureate in literature and religion of what else but Jacksonian individualism itself. A kindred occult similitude of self-advertising styles between “shitposters” extraordinaire Joyce Carol Oates and the man she will only call “Tr*mp” has been noted in the comments section of this very Substack.

There is no “right side of history,” only a general oblivion from which a few inspired tesserae or tesseracts may be recovered; we hope they will inspire us toward the universal emancipation of the human soul, unconstrained by party, sect, or identity.

There is really nothing more important than contemplations of the historical development of modern literature that do not use the word 'stream-of-consciousness' - thank you for this.

Jane Austen, I think, fits into the schema very well, truly the peak of literary unlyricism. I think, perversely, the hollowing out of irony (which might be the same thing as the hollowing out of 'dialogue' or 'the social') is a key factor here; lyricism always signifies isolation. But really, the whole thing is incredibly mysterious and hard to explain, and this essay of yours is a wonderful starting point.

I remember stumbling upon this essay in my first year of undergrad four years ago and you may be happy to know that I've returned to it often as I've attempted to come to my own thoughts around the persistent influence of Romanticism.

On a different note, despite your division between poetry and the novel in the footnotes, would you say (and apologies if this is the general subtext of the essay) that the modernist novel as described above with its intense Romantic versification of the consciousness extended to a plurality of habits and affects (characters, we might otherwise say) acts as the artistic synthesis of poetry and novel that is a potential solution to the problem of creating a counterculture that doesn't annihilate the angel in the home? For example, Woolf in To The Lighthouse and Mrs. Dalloway is both showing women progressing out of the domestic space while appreciating what these women were and the significance of their former social position, an act which is made possible through the ability of the novel form to allow for a wider range of perspectives through its community of characters (its liberalism, perhaps) combined with the sympathy involved in intensely inhabiting each character's subjectivity (or is the core of the problem that no matter what Mrs. Ramsey does have to die and can only be mourned?). I feel as if I'm more or less repeating Iris Murdoch's injunction, which you previously quoted in the 95th iteration of these weekly posts, that "A novel must be a house fit for free characters to live in" with its useful alignment of the form itself with the domestic space. But then again the whole issue is that the conundrum remains, so either the world hasn't yet caught up (this is where I admit I'm behind on the IC Ulysses lectures so I haven't yet indulged in your reading of the novel as the esoteric blueprint of our time) or we must resume our peregrinations in search of new and beauteous forms.