A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week, I released “Love, Says Bloom,” my latest episode of The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. This one covered chapters 10 through 12 of Joyce’s Ulysses in our summer reading of the Joycean oeuvre. If last week’s episode, immersed in Shakespeare, forced us to confront Joyce’s idea of literature, this one brings us face to face with Joyce’s politics: a utopian cosmopolitics, a fugue state of the nation, that recoils in moral terror at any and all politics of identity. For my new readers, the first Ulysses episode, “Signatures of All Things I Am Here to Read,” is free in its entirety if you’d like to sample the wares. A paid subscription grants you access to what is already a 25-hour archive of episodes on modern British literature from Blake to Beckett. After Ulysses, our summer reading turns in August to George Eliot’s Middlemarch. In the fall: American literature from Romanticism to modernism, from Emerson and Poe to Stevens and Faulkner. 1

While my new novel, Major Arcana, has gone into eclipse as we await its rebirth in a Belt Publishing edition in 2025, a paid subscription will also grant you access to its original serialization, including audio versions of each chapter. You might also please consider my previous publications while you wait. In the vast comments section to last week’s newsletter, a reader inquired about my three other novels (which to read first, what order to read them in, etc.): Portraits and Ashes, The Quarantine of St. Sebastian House, and The Class of 2000. Each of my novels stands alone, so you can read them in any order.2 Aside from that, another reader, David Telfer, was kind enough to provide for the first commeter a very thorough guide to my oeuvre, part of which I quote with gratitude here:

If I had to choose one, I'd say “Portrait and Ashes” is the minor arcana to the major deck of John’s masterpiece. And if I may clumsily extend the analogy further—perhaps to aid in your preparation, given your explicit request, though I confess my knowledge of Tarot is limited—I’d liken them thus: “Portrait” is the suit of cups (divinations of emotion), “Quarantine” the suit of swords (ruminations of the mind), “Class” the suit of coins (cultivations of material), and “MA” the suit of wands (the will of art, the art of the will, and indeed, like all our most ambitious literature, striving in its own imperfect way for the man, the maelstrom, at the centre of our canon, the art of Will).

Whether you choose to read all, or some, or one (or, heaven forbid, none!) of his novels, I hope you discover as much profound delight in, and can instructively quarrel with, his works as I have over the years.

For this week, I posit a literary binary of the kind many of my readers seem to enjoy and resent in equal measure. (Don’t worry, I’m going to resolve it!) We’ve had Tolstoy vs. Dostoevsky and Melville vs. James. Now please gird yourselves for Pound vs. Stevens. It’s a showdown between history and poetry,3 with guest appearances from Joyce and Flaubert and Foucault and the Great Goddess, not to mention my usual scandalous footnotes. Please enjoy!

In for a Penny, in for a Pound: The Modern Writer and/as the Total Subject

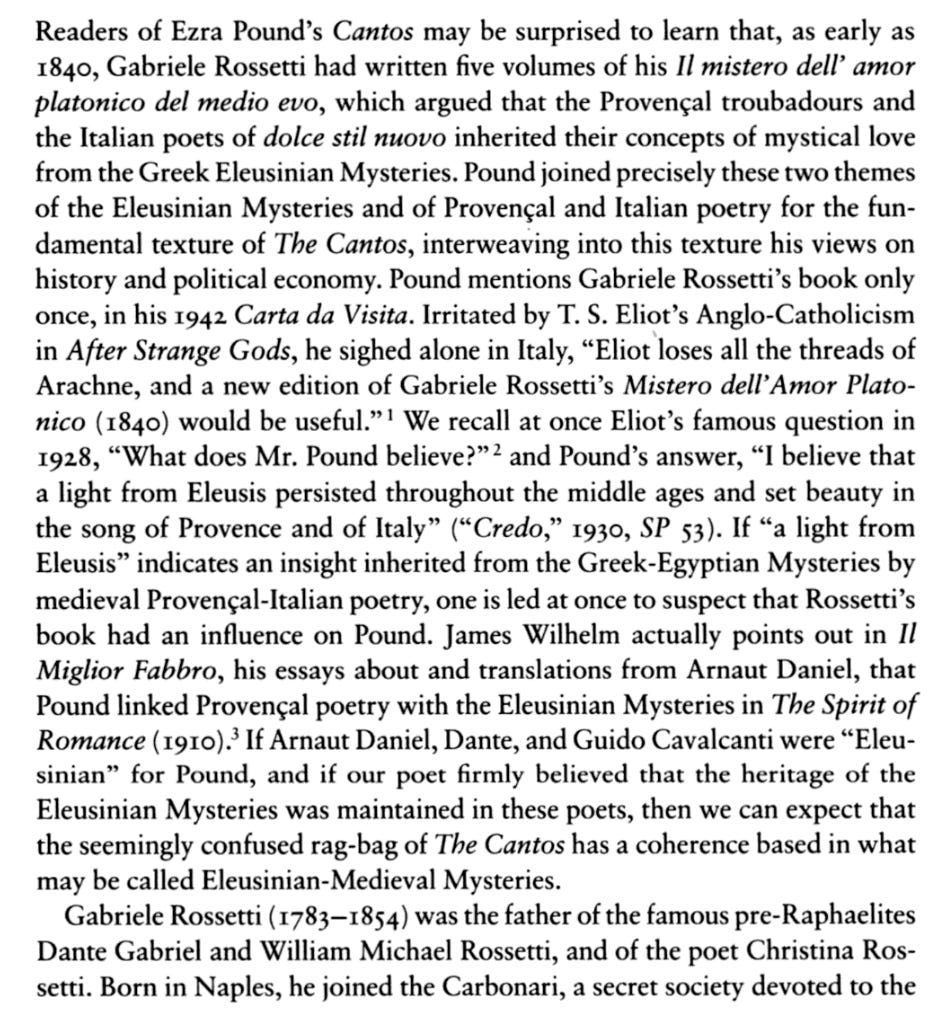

After my footnote from last week on Ezra Pound and the Eleusinian Mysteries, I could not in my endless pursuit of coincidence and synchronicity help but notice that the notorious Michael Crumplar announced he was also reading a book on the same subject, Ezra Pound and the Mysteries of Love: A Plan for The Cantos by Akiko Miyake (Google Books screenshot below). Like Leon Surette’s Birth of Modernism, the book I cited, Miyake’s treatment of the subject apparently hinges on Gabriele Rossetti’s 19th-century conspiracy theory of the canon; I touched on this rather psychedelic topic in “The Mind Has Mountains,” a non-paywalled Invisible College episode on Christina Rossetti and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

Then Alice Gribbin posted “The Serious Artist,” a sequel to the Manifesto! podcast appearance that occasioned my last week’s footnote in the first place. Alice creates a Poundian collage or montage of the poet’s words and her own to create a new manifesto denouncing the aesthetic slackness of our time, a poetic gambit somewhat amusingly misunderstood down in her comments section by a certain Herr Grund:

A fatal tolerance of mediocrity has many causes, among them the employment of a majority of artists in the apparent role of educating the next generation in their form. These artist-teachers, in seeking only to nurture within their protégés the speck of the relative good, forgive the blindingly pervasive bad. Their generosity of instruction dims their judgment, numbs them to the derivative, so that they themselves, unsuspecting, produce art that cannot be other than complacent. The teaching poet’s audience is shrunk down to the schoolroom, the poem to an object for supervised discussion among fee-paying youths.

But, though Alice can be seen in my own comments section of last week cautioning me against literary critics, I also read the Marjorie Perloff essay she recommended on her pod appearance, “Pound/Stevens: Whose Era?” In this 1982 essay, the late Perloff stages an epochal confrontation over the meaning of modernism between the devotees of Pound (Hugh Kenner, Guy Davenport, herself) and those of Wallace Stevens (Harold Bloom, Helen Vendler, Frank Kermode).

According to Perloff, the Poundians favor a Cantos-style collage or montage “poem including history,” an objective and formalist spatial arrangement of temporally disparate cultures, over the solitary-voiced Romantic lyric of the soul in conversation with itself or its interior paramour as one finds it in Stevens. Pound’s poetry is objective, historical, and political; Stevens’s is subjective, experiential, and personal. For the Poundians, the Stevensians are solipsists trapped in a narcissistic circuit of self-flattering emotion; for the Stevensians, the Poundians are a company of totalizing esotericists with delusions of both personal objectivity and political grandeur.

Though I have been affably accused of dealing in culturally binary critical thinking myself, I find Perloff’s an unfortunate divide. Do we really need to make an absolute choice between these two modes of poetry? Can we not have both a poetry of history and a poetry of self? Some poetry more focused on the means of expression and some more focused on what is expressed? With a gun to my head, I would choose Stevens over Pound, precisely because I trust Stevens more than I trust Pound not to put a gun to my head. But also because Pound’s own practice betrays him as a Stevensian in the end, as we may witness from a sample exegesis of Perloff’s:

The first step in dealing with that surface is, of course, to track down Pound’s endlessly teasing allusions. Why does “Taishan” appear in line 2 of Canto LXXXI? Because the high peak seen from his prison cell at Pisa reminds the poet of the sacred mountain of China, the home of the Great Emperor. And where does the Mount Taishan motif reappear? Some sixty lines later, when “Benin” (the friendly Black soldier whose face reminds Pound of a Benin bronze) supplies him with a “table ex packing box,” a gift “light as the branch of Kuanon.” Kuanon is the daughter of the Emperor, the Chinese goddess of mercy.

If these allusions are present in the poem because Pound was “reminded” of them, then we are in the Stevensian realm of subjectivity after all, not on the crystalline terrace of an objective and timeless history where Confucius treats John Adams to tea as they discuss good governance and draining the Pontine swamp.4

But still, as the astrologers would insist of my ascendant Libra, I posit stark binaries only so I may challenge myself to make peace between them in would-be ingenious syntheses. I am re-immersed in Joyce at the moment, so I largely thank Perloff for giving me a new language in which to express what Joyce was doing: using Poundian means for Stevensian ends. Joyce arrays a dazzling collage or montage of blinding facts all in service to the total exposition not of history (history is a nightmare from which he is trying to awaken) but of his infinite consciousness, which is also ours. (And I think it’s fair to count Joyce among the poets.)

While I’m citing the dreaded critics, I quote from a scholarly essay attempting to redefine the whole of modernism along what Perloff would call Stevensian lines, Jerome McGann’s “‘The Grand Heretics of Modern Fiction’: Laura Riding, John Cowper Powys, and the Subjective Correlative” (Modernism/Modernity 13: 2, April 2006):5

Powys and Jung thus read Joyce black where Eliot reads him white. For them, the order that Ulysses sets in play is not Eliot’s formal or structural order, it is rhetorical. When Powys and Jung read Joyce they emphasize the book’s subjectivity, reading the writing as a kind of monodrama. In this respect the precursors of Ulysses would be Byron’s Manfred, almost any of Poe’s stories, Tennyson’s Maud. The writing is a play being staged by Joyce in which (or so that) readers can discover their parts. The analogue with Brecht seems clear. The novelty of Ulysses is how it exposes the work of fiction not as a text or a document but as a field of discourse where readers are assumed to be present: the reader being a “hero” of the writing, as Bakhtin would say. An adequate response to the book is thus emblematized in Jung’s “Monologue” or Powys’s nakedly personal reading. In this view, Eliot’s reading would itself be seen as completely idiosyncratic, the rhetorical performance of a neo-classicist trying to keep his feet and point of balance, like Dr. Johnson in another, equally volatile age.

As Leopold Bloom thinks of his “joys” in Ulysses, “All are joys,” which I interpret to mean “all are Joyce.” Joyce was preceded in his monodramatism by his beloved Flaubert. I was reading Flaubert’s own monodrama, The Temptation of St. Anthony, this week, the delirious fantasia or phantasmagoria he obsessively researched and wrote all his life while producing his more renowned and abstemious realist masterworks. As the titular saint is beset with a bevy of heresiarchs, gnostics,6 gods, goddesses, monsters, and finally the rudiments of life itself—this matrix of matter is the final goddess, the book’s final secret, like the subterranean Mothers in Goethe’s Faust, to which The Temptation pays generous tribute—Flaubert indulges a taste for every form of occultism and madness.

Flaubert was research-crazy, as I am not, but still, I was glad to see some figures from the Major Arcana research turn up. Major Arcana isn’t a strict mythic-method book, but I’d be lying if I said Simon Magus and Helen of Troy didn’t cross my mind when writing of Simon Magnus and Ellen Chandler, or Diana of Ephesus vis-à-vis Diane del Greco. But as Julianne Werlin sagely observed, Major Arcana is a book about how not to get trapped in books. The Temptation is just the opposite. It is the first book made solely out of books rather than out of experience: the first modernist or postmodernist book, the literary work that ended history, way back in the middle of the 19th century, Flaubert not only our contemporary but still out ahead of us.

Or so everyone’s favorite French immoralist, Michel Foucault, claimed in his celebrated 1967 introduction to the novel, “Fantasia of the Library,” which I quote here in the translation of Donald F. Bouchard and Sherry Simon in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice:

It may appear as merely another new book to be shelved alongside all the others, but it serves, in actuality, to extend the space that existing books can occupy. It recovers other books; it hides and displays them and, in a single moment, it causes them to glitter and disappear. It is not merely the book that Flaubert dreamed of writing for so long; it dreams other books, all other books that dream and that men dream of writing—books that are taken up, fragmented, displaced, combined, lost, set at an unapproachable distance by dreams, but also brought closer to the imaginary and sparkling realization of desires. In writing The Temptation, Flaubert produced the first literary work whose exclusive domain is that of books: following Flaubert, Mallarmé is able to write Le Livre and modern literature is activated—Joyce, Roussel, Kafka, Pound, Borges. The library is on fire.

Whether this is in fact true of Joyce—it seems to me not quite—will be the continuing burden of The Invisible College. Whether it is in fact true of me will have to be decided by my readers. Dr. Werlin sagely diagnosed me as still afflicted with modernism. This may be the painful case, but at least I will be in good company—good literary company, anyway.

But what strikes me further is the similarity among our four grand modern poets—Flaubert, Joyce, Pound, Stevens—beyond their differences. All four—yes, Stevens too—worship the great goddess. Flaubert has his “immensities” and “countries of the ocean,” the amnion of the universe, with which his ironical version of a Paradiso concludes; Pound encodes his Eleusinian Mysteries, his cult of Demeter and Persephone, his marriage at Eleusis; Joyce showcases his Penelope/Molly and her concluding universal affirmation, not to mention his more alluvial Anna Livia Plurabelle riverrunning our total dream; and Stevens—yes, even skeptical Stevens—regales us with his “fat girl, terrestrial, my summer, my night” whose theophany brings Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction to their climax. Thus—even if Herr Grund despises a montage—do figure and gr(o)und become one.

And if all this crooking of the masculine knee to the fancied feminine earthly-divine seems cloying and self-serving on the part of these last sons of high culture, I invite you to read or reread “New Gods Are Crowned in the City,” a little piece I wrote back when I had a quarter the subscribers I do now. It’s about where we and the goddess find ourselves in the present moment, about how far we’ve come, from outer and inner space to the very pinnacle of the law.7

And for new readers who find The Invisible College’s selection of authors excessively white and/or male, I draw your attention to my YouTube channel featuring over 60 free lectures on 20th- and 21st-century American literature originally prepared for diversity-focused courses at the University of Minnesota. There you will find discussions of Langston Hughes, Nella Larsen, Gwendolyn Brooks, James Baldwin, Lucille Clifton, Ishmael Reed, Leslie Marmon Silko, Maxine Hong Kingston, Gloria Anzaldúa, Marilyn Chin, Louise Erdrich, Jhumpa Lahiri, Junot Díaz, and more.

I resolved early on that each of my novels would stand alone. I never wanted a reader to chance upon a book of mine and then put it down because it’s not the first in some sequence. No sequels, no prequels, no trilogies, etc. I won’t even break this rule—well, not yet anyway—for my occasional fantasy about how a conversation between Alice Nicchio-Strand and Ash del Greco might go.

Speaking of history, I promised Dan Oppenheimer I’d say something here about certain socio-political themes related to the lower middle class and radical politics and my old review of Angela Nagle’s Kill All Normies—a totally failed prophecy of a review; so much for my occult powers!—but I think I will with apologies postpone that rumination given the current instability of American politics. Suffice it to say that if my prophecy of American reconciliation in the 2017 review were ever to come true at the level of capital-P politics, it would come true this year. If I were a gambler, I might bet that the most consequential date so far of this election year was not June 27 (the debate) nor May 31 (Trump’s conviction), but April 22. I will elaborate when the time is ripe. If I forget to do so, or if I forget I made this intimated prediction and it turns out wrong, please don’t hesitate to bring it to my attention and make fun of me—if we’re not incinerated, that is. (The YouTube astrologers all say Trump in 2025 and world war in 2026. After that, we may enjoy the Age of Aquarius and its promise of new heights of human freedom. One even says we’ll all become telepathic, just as we were in the Age of Leo, before the Age of Cancer individuated our Neolithic forebears in their newborn cities. Then I won’t have to write these; I’ll just think them in your general direction.)

One is tempted to make some political imprecation against Pound here, but Stevens seems to have hated black people about as much as Pound hated Jews, so there’s nothing moral to choose from between them. These people aren’t our friends; that’s not what they’re for. I quote Louise Glück, who liked Eliot more than she liked Stevens and never (to my knowledge) even mentioned Pound; she was talking about fictional or indeed mythological characters, but poets for my purposes are fictional characters, indeed mythological ones:

You are allowed to like no one, you know. The characters are not people. They are aspects of a dilemma or conflict.

Nothing moral here to choose from, I said, and I meant it, but politically I am probably more in sympathy with Stevens’s libertarianism than many of you are. A shrunken state can’t help anybody, but ideally it can’t hurt anybody either—it can’t hurt the people the poet hates, for instance. His libertarianism is why Stevens’s racism genuinely matters much less than Pound’s does: it is not an inextricable part of his poetry, because his poetry is not a totalizing political statement about the total political state.

Many connections here to what Sam Kriss has called the John Pistelli-verse. I once discussed this essay with Paul Franz, who is not the first to tell me I must read Powys, which, except for some essays, I have not yet done. Laura Riding was the subject of a Blake Smith Tablet essay, and is also I believe an interest of Mars Review editor Noah Kumin’s, who has in his own pursuit of the Perennial Philosophy further recommended The White Goddess by Robert Graves, Riding’s one-time consort who claimed he stole and vulgarized the goddess idea from her. Riding and Graves, for whatever this may be worth, named modernism in the first place.

(This kind of footnote is something like a Poundian ideogram, with its dizzying connections between disparate elements and its verbal spatialization of a historical sequence. It belongs in the footnote of a Substack post, but I probably wouldn’t commit it to print. Pound is an online poet, Stevens a poet we go to when we weary of the—note the spatialization of the temporal in the very word—timeline.)

Flaubert’s main source for gnosticism was the scholarship of someone named Jacques Matter. You can’t make this shit up!

I didn’t mention Neil Gaiman in that post, speaking of cloying and self-serving men, though his Sandman, with its vengeful Triple Goddess, definitely has a place in it. This week, the Kindly Ones at last began their pursuit of our author himself. Grant Morrison always used to say he got the idea of using his comics to get laid by inserting his desired sex object as a character from Gaiman, who would get mobbed by Death-looking goth girls at readings and conventions, but this fact seems to have been lost on Gaiman’s readership until the scandal broke. (The scandal appears to be in some peril, however, with the media tribunes of the accusers themselves ideologically suspect, and with Netflix having possibly sunk too much value into Sandman already.) I taught Sandman a few times in the last couple of years on the occasion of the Netflix series, and I told my students not to be taken in by Gaiman’s bumbling Englishman “I’m just a humble little boy” Hugh Grant routine. “He’s a shark,” I warned them. I meant literarily, but not just literarily. Then we made a study of his ruthless pursuit of a female audience, both in his comics’ text and in their subtext, and we talked about the ways in which this might be a laudable gesture, and the ways in which it might be less salubrious than appears on the surface. I can offer no adjudication of the charges against Gaiman, which seem ambiguous, though what he’s overtly admitted to is damning enough by the standards of his readership, and in line with how I’ve come to understand his persona. Grant Morrison, I might add, accepted his rather forced they/themming shortly after the comparable MeTooing of Warren Ellis, who likewise (allegedly) exploited his youthful female admirers—thus, among other reasons, why I don’t and won’t bother with the they/them in Morrison’s case, not, to be fair, that he ever quite requested it. I repeat: these people are not our friends. That’s not what they’re for. Gaiman’s Sandman and Morrison’s Invisibles remain cultural landmarks—Ellis’s work less so, though Planetary is certainly memorable—and I’d never tell anyone not to read them based on the behavior of their authors, much as Gaiman’s oleaginous moral posturing does put one off. Here in the amoralist halls of Grand Hotel Abyss, in dealing with the reprobate author, whether fan-exploiting comic-book scriptor or fascist-supporting modernist poet, we operate on two principles. (Fun fact before I give the principles: the penultimate issue of Gaiman’s Sandman series was stylistically based on Pound’s Chinese translations.) The first was articulated by Michael Hofmann in a decade-old interview:

Americans are apt to think of books as potential contaminants anyway. “My God, I’m not reading a Fascist here, am I?” A little bit the same with Pound, who was much worse [than Gottfried Benn]. Of course you have it with all of the modernists: Eliot, Lawrence, Virginia Woolf, Joyce. But you have to read them. You have to read worse people than that. You have to read Céline. Worse people than that—I can’t think who at the moment. You can’t be bien-pensant and care about literature.

The second by Simon Leys in an essay in his Hall of Uselessness:

It is not a scandal if novelists of genius prove to be wretched fellows; it is a comforting miracle that wretched fellows prove to be novelists of genius.

Speaking of literary binaries: further reflection on "Major Arcana" leads me to see it as a study in binary oppositions that nevertheless interpenetrate and interact with each other: art vs. life, male vs. female, boundaries vs. freedom, progressive vs. reactionary, virtual vs. real, aesthetic vs. commercial, all of it laid out on the "trinary" of past vs. present vs. future (the boundaries of which threaten to dissolve at certain points in the book).

Well hey: we live in the binary (digital) age, don't we? All those 0s and 1s. I guess what I'm saying is I look forward to re-reading and re-reviewing it when the Belt edition comes out - it will be interesting to see what impressions of it I have then.

I have the giant two volume Kenner/Davenport letters staring at me rn next to a book on Ming China, and the last time I read Harold Bloom I felt like someone was playing a prank on me, so I guess you could say I've chosen a side. To give it its due, that school of modernism at its best gives me this almost psychedelic sense of awareness; I step outside and every leaf on every tree seems charged with beauty and meaning and I feel a sense of awe at being part of this greater consciousness. Because it is situated *in* the world and in history it makes me want to go out into the world and do things, spend time in nature, read as widely as I can, travel, talk to strangers etc.

(Of course, my imaginary interlocutor argues, maybe mapping the interior of the self a la Stevens is the real work and this stuff is all just a temporary high, a flashy manic phase. But what are you gonna do.)