...an Author feels as if he were dismissing some portion of himself into the shadowy world, when a crowd of the creatures of his brain are going from him for ever…

—Charles Dickens, Preface, David CopperfieldI am happy to announce that my newest novel, Major Arcana, is now available in print and ebook editions from Amazon. Readers who prefer books now have the opportunity to read what some are calling a “major” novel.

I have also added a pdf of the book version to the post “Four Complete Novels for Paid Subscribers.” The archive of the serial will remain available on here.1

I will send a free pdf of the book to anyone who pledges to review it in a public forum. I will mail (or have Amazon ship) a free review copy of the print edition to any editor or writer who would like to review it in a prominent publication. Interested parties can contact me at johnppistelli@gmail.com or DM me here on Substack.

Now, for those who have traveled with me on this journey for over a year, a few afterthoughts on this, the biggest and boldest novel I’ve ever written. Consider it a Postface to go with the Preface.

About the prices: I kept the print edition as cheap as I could, but Amazon has a price floor based on the physical size of the book. The Kindle edition is priced competitively relative to ebooks from mainstream publishers.

I know it’s a long book. But it was written not only by someone who wrote a doctoral dissertation on those high modernists Joyce and Woolf, but also by someone whose earliest adolescent models of the serious novel were the popular and populist Johns Steinbeck and Irving. In other words, I know how to keep a big book in lively motion without sacrificing intellectual, ethical, or even formal complexity. You’ll read it in a week, I promise.

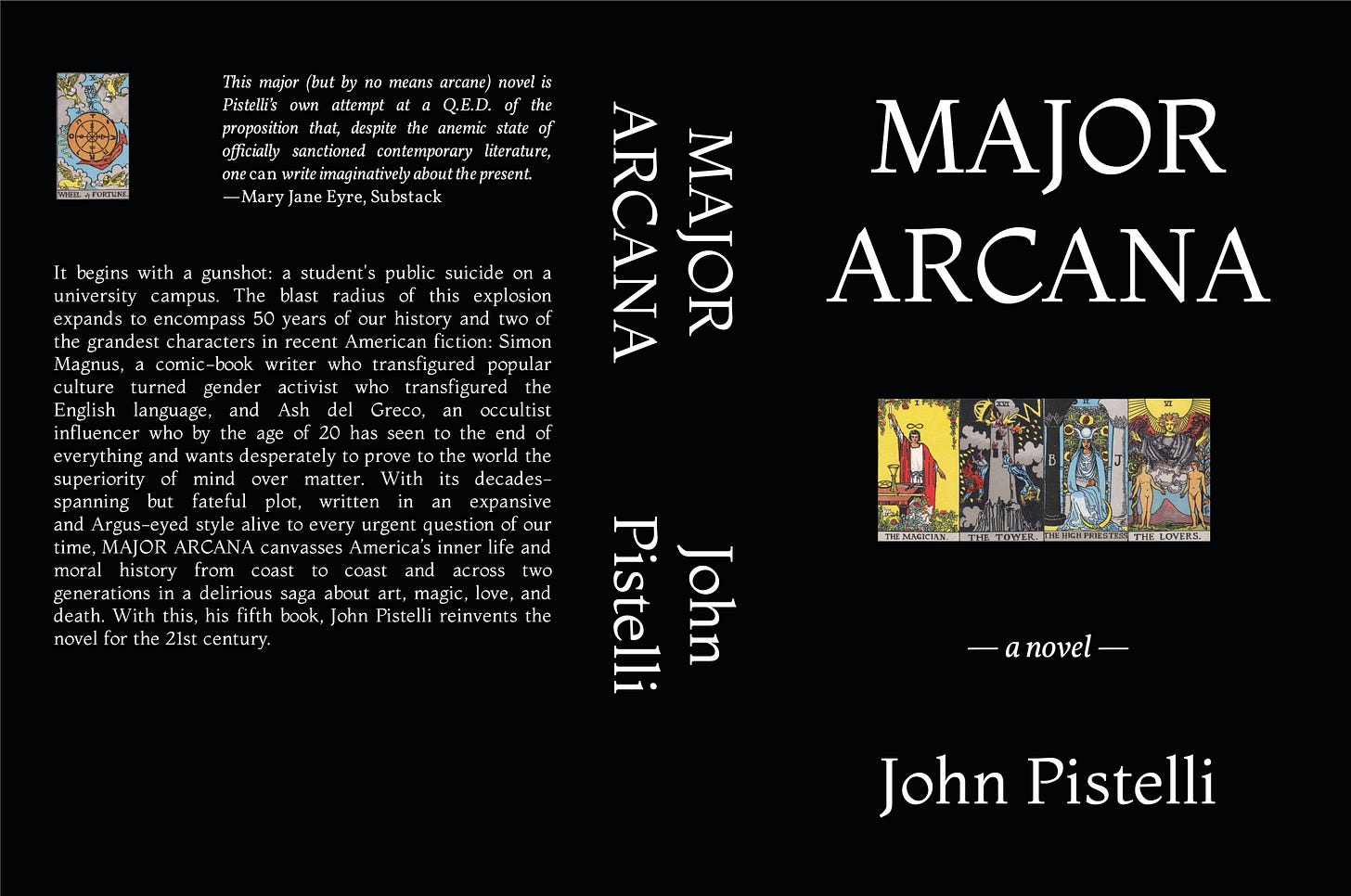

The best and worst thing about independent publishing is that you have to make your own cover. I do use the templates Amazon makes available; once you find your way around their system, you can do with those templates pretty much whatever you want. Part of me wanted to create a design that evoked the postmodern multimedia surrealism of the Dave McKean Sandman covers in tribute to the ’90s comics that inspired the novel.2 This is beyond my own graphical capabilities, however, and I decided that simplicity would be best anyway: a big black book, like an old Bible, with a free Tarot spread for the reader on the front. The four Tarot cards I chose loosely correspond to the narrative’s four parts between Chapters 0 and ∞. I am indebted for the visuals to the great Pamela Colman Smith—a debt repaid in the text itself with my protagonist Simon Magnus’s sincere tribute to the Tarot artist.3

I put the Wheel of Fortune on the back cover in place of the author photo for good luck: a little sigil magic for my chaos magicians. The blurb comes from Mary Jane Eyre’s review, still the best introduction to the novel, better than my Preface. The back-cover copy may seem bold in its claims. But if you’re in the independent-publishing game, you have to get used to singing your own praises. There’s no real difference between writing about how great your book is and having a marketing department do it for you: either way, you think your book is great, or else you wouldn’t invite the public. There’s no point, then, in hiding your light under a bushel.

You’ll notice I didn’t provide much about the novel’s plot on the back cover. Personally, my eyes glaze over whenever I encounter an extensive summary on the jacket, back cover, or online description of a novel: a bewildering flurry of names, dates, and events that are meaningless outside their context in the work of art itself. Too much information—just tell me what the book is like! I also want to resist the BookTokified demand for ever more preliminary information and labeling on novels, which resembles the general vogue (and sometimes institutional demand) for social self-labeling that Major Arcana frankly wages a furious polemic against. A serious novel is a leap of faith, for writer and reader, just as a person is. No amount of preliminary categorizing can save you from a true encounter.

“Comic book” and “gender” appear on the back cover, but I decided to advertise the novel neither as picking up where The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay leaves off (though it does) nor as intervening in our gender war (though it does that too). I thought the former would be misleading, and the latter sensationalistic. Plus, the eras of the superhero4 and of youth gender radicalism5 appear both to be winding down, which makes Major Arcana less an intervention in a live debate—always a precarious position for a novel to be in, as if a novel were no better than a newspaper editorial—than a monument to the vanishing present, designed for permanence, or for as much permanence as art can manage on this earth.

I confess that I under-emphasized in both the Preface and the back-cover copy how magical this novel’s magical realism gets. But “magical realism” is a somewhat tarnished label, suggestive of bad corporate multicultural fiction, of world music CDs in ’90s coffee shops or the lesser selections of Oprah’s Book Club, whereas I am after a higher vision than that. Besides, it’s called Major Arcana and has Tarot cards on the cover—you were expecting Zola or Franzen?

I try to impose upon myself a unique linguistic constraint in each of my novels. I don’t remember what they were in The Class of 2000 or The Quarantine of St. Sebastian House, though. I know that Portraits and Ashes doesn’t use any m-dashes; the prose flows rather than breaking and fragmenting. In Major Arcana, no sentence begins with a coordinating conjunction. I’m not sure what that means, but it feels right. The grammarian-nuns back in Catholic school told us we must never begin a sentence with a coordinating conjunction, so maybe I obeyed that single dubious rule in the superstitious hope that it would guard me against divine sanction for all the novel’s religiously proscribed occult traffic. We can only hope!

Our revels now are ended. I’ve never written a book with more pleasure, and, as the master manifestors would say, I intend that you’ll read it with equal pleasure. Thanks again to all my readers! And, as the controversial Alice Walker once wrote at the head of one of her own novels, thanks to everybody in this book for coming.

I made a few cosmetic changes between the serial and the book, but nothing substantial. If you’ve read the serial, you’ve read Major Arcana. Professional reviewers—as well as future academic researchers sifting through the ruins of our civilization—are encouraged, however, to cite the print edition.

Dave McKean would be the inspiration for Major Arcana’s Duncan McGinnis if only he (McKean) were half-Jewish and descended from a Holocaust survivor. Nevertheless, I was inspired to make my McKean-like character a half-Jewish descendant of a Holocaust survivor not only because it adds to my novel’s thematic architecture, but also because of the influences and motifs in McKean’s own work, especially his graphic novel, still one of my all-time favorites, Cages.

And for any lawyers out there, I made sure to use public domain images from the Rider-Waite deck—scans of cards dating from 1909, as found on Wikipedia—for my cover image.

I refer to the recent Marvel movie flops and Disney’s subsequent cancellation of some forthcoming superhero projects. Major Arcana is not about lighthearted and quippy Marvel-style superheroes, however—I’ve hated those since my age was in the single digits—but about the Dark Age of superheroes associated with the DC Comics of the 1980s and ’90s, particularly those authored by writers of the so-called British Invasion like Alan Moore and Grant Morrison. Still, I decided early in the project not to make Major Arcana’s Dark Age comic-book writer Simon Magnus a working-class Briton, but rather a New England blue-blood. I went to the root of the American Gothic imagination in our Puritan heritage, our trespass into the New World’s “moral wilderness,” and I further linked my own novel back to the tradition of American romance inaugurated by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Moore and Morrison remain influences on all my work, however. Attentive readers will notice that for Simon Magnus I borrowed Moore’s bitterness and regret over his past work, his formalist genius, and his drive to aggress against the reader, while from Morrison I took the excitable visionary rhetoric, the explicitly gnostic spiritual ambitions, and the metamorphic personal identity (including gender identity).

For this information, I draw on survey data recently shared on X. There are fewer Ash del Grecos and Ari Alterhauses among those in their teens and early 20s today, perhaps by half, than there were five years ago, when those characters’ high-school years are set. In addition to what I said about the novel’s gender politics in the Preface, I will repost here a text that appeared as a footnote in an old Weekly Readings. This is the closest I am willing to come to a disclaimer for those on all sides of the gender wars who may be dissatisfied with my approach, based as my approach nevertheless is on several different varieties of personal experience and observation:

All of the concessions made in Major Arcana to the sensitivity reader in my head take the form of little scenes meant to clarify that this ontological androgyny of the artist is the novel’s theme, not transgender identity. The confusion of these two subjects is one of the social, political, and even medical defects of our era, and on “both sides.” It’s why, for example, as a number of bemused centrist commentators have pointed out, there are plenty of high-profile transgender conservatives but no nonbinary conservatives, since “nonbinary” signals a political commitment facilely equated with metropolitan artistic identity as much as it does anything else—though I would argue that the political and the aesthetical-metaphysical are being fatally conflated in this case, too, and that everybody would be better off if they paid almost no attention to politics, democracy being, for all practical purposes, presently inexistent anyway. Hence I occasionally bring normie transgender characters onstage to say to Simon Magnus and Ash del Greco, in effect, “You’re not trans—you’re crazy,” “crazy” here meaning, in normie terms, an artist. One may of course be trans and an artist, i.e., crazy, just as one may be cis and be an artist, but the problem of the artist aspect of the soul’s essential androgyny remains and cannot be dispelled simply by adherence in every other area of life besides art to masculine or feminine, whether cis or trans. My sole concession to the otherwise fascistic #ownvoices mentality is that the trans artist’s specific negotiation of this complex subject is almost certainly best left to trans artists themselves to explore. As far as Simon Magnus and especially Ash del Greco go, however, they in their particular craziness essentially are #ownvoices characters. As Jack Kirby strangely and wonderfully once said of Galactus, I’ve known them for a long time.

Excited to get my hands on the print edition! I started out with the serialization and loved it, but then lost track sometime in the fall and never caught up so I’m excited to finish in print! I’m surprised by the page count as well, this really is your epic.

Looking forward to buying and receiving the physical copy! Our poor coffee table will have to give up even more of the little book-less surface it still has left. My reading in 2023 was full of slight novels, but in 2024 I'm already reading Middlemarch, with Major Arcana to come. This may be the year to reread Ulysses, given the other thick-spined company.