A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

A big week here at Grand Hotel Abyss. First, we saw the book publication of my novel Major Arcana, first serialized for paid subscribers right here on Substack. You can buy the book here. I want to thank everyone who’s purchased the print or Kindle editions already. The serial remains available for paid subscribers; paid subscribers can also download a pdf of the print edition here. Let me repeat that I will send a free pdf to anyone who emails me at johnppistelli@gmail.com or DMs me on Substack in return for a pledge to review it in a public forum. I will mail (or have Amazon ship) a print edition to any editors or writers who would like to review the novel in a prominent publication. If you’ve read the book, please do leave a review somewhere. I tend to receive even dispraise as an observation of my unique attributes, so mixed or bad reviews are welcome,1 provided they’re thoughtful—please just spell my name right!

I didn’t plan it this way—you know what everybody’s favorite Swiss psychiatrist calls it when that happens—but I published the novel the same week I released my lecture on master novelist Charles Dickens and his Hard Times for The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. Dickens was one of Major Arcana’s tutelary spirits—I reread Great Expectations before I started writing the novel for a reason—and my lecture, entitled “In a Circle of Stage Fire,” is accordingly the longest and most intense of The Invisible College episodes so far as I join Dickens’s just war against the reductionists while heading off his threatened rendezvous with fascism. Please subscribe today to support this cultural work!

To let the dust from the above explosions settle, I offer a somewhat casual post for this week. I list three more synchronicities related to the publication of Major Arcana, the release of my Dickens lecture, and cultural and political news. Please enjoy!

Synchronicity #1: Where the Id Was, the Egirl Shall Be; or, The Triumph of the Petite Bourgeoisie

As a longtime observer—since 2019!—of the reactionary avant-garde, I did notice that egirls were added as an investment opportunity to the blockchain this week.2 I didn’t think much of it, however; we’re coming up on two years since my podcast interview with the perceptive Katherine Dee, but I confess I still don’t understand crypto, Urbit, etc. any better than I did then.

It is either one of my biggest flaws or one of my biggest virtues that I am not susceptible to economic thinking. I believe it’s a virtue. Mallarmé said that everything will end up as aesthetics or economics, and maybe he’s right, but it seems to me that economic thinking has deranged and distorted many a literary mind across the whole 20th century and from left to right on the political spectrum, whether we consider Ezra Pound or Fredric Jameson. My Ph.D. advisor, about whom more in a moment, was always recommending Mary Poovey, but Mary Poovey wrote books with titles like Genres of the Credit Economy, a sequence of words that makes my brain short out.

On the other hand, she (my advisor) also recommended Rita Felski’s rumination on the petite bourgeoisie, which turned out to be fruitful for my own thinking, even my sense of belonging by birth to a universal class, for the development of which argument please see the beginning of my essay on the great Australian poet Les Murray. “Their class origins cannot be assimilated into a discourse of progressive identity politics,” writes Felski of us lower-middle-classers, whether we are Murray or Pistelli or Felski herself—and whether, more to the point, we are Keats or Dickens or Joyce.

When I decided as a teenager that I would never work a real job even though I was not born to the class permitted to avoid such remunerative labor, I decided further that I wouldn’t think too much about money and just trust that what I needed would come in time. It’s a faith no less dangerous now than it was then, but it’s served me in good stead so far. Even if I die in the proverbial ditch, I will die in the satisfaction that I never railed against “the Jews” on Italian radio or proposed universal conscription as a plot to make America communist at last. Such is where economic thought leads.

The alternative, as evidenced by fascist and socialist poet-thinkers, appears to be hatching hateful conspiracy theories about why I’m not rich and they are, whomever they happen to be. I have avoided petit-bourgeois fascism by embracing petit-bourgeois libertarianism. It’s true that he was living on his dead wife’s inheritance, but still, Emerson wasn’t all wrong when he wrote this in his journals:

When men feel & say, “Those men occupy my place,” the revolution is near. But I never feel that any men occupy my place; but that the reason I do not have what I wish, is, that I want the faculty which entitles. All spiritual or real power makes its own place. Revolutions of violence then are scrambles merely. (qtd. here)

What does this have to do with the addition of egirls to the blockchain? As I said, I barely know what those words in that order even mean, but, in my Ozymandias-like surveillance of social media, I couldn’t help but notice that friend-of-the-blog and Mars Review of Books editor Noah Kumin interpreted the event as what else but the triumph of the petite bourgeoisie:3

Synchronicity #2: Love Lies Queering; or, The Gayest Thing Ever

On the eve of Major Arcana’s publication as a book, I observed on Tumblr that two phenomena the novel depicts at length—the pop-culture hegemony of the superhero and the spread among youth of nonbinary or genderqueer identities—appear to be on the wane. The novel by its conclusion suggests that such wanings are in the course of things; all novels, no matter how ruthlessly contemporary, become historical novels in the end. To these observations on Tumblr, I added the following note:

This (i.e., the aforementioned nonbinarism) was sometimes discussed by the gender-critical contingent under the rubric of “the disappearing lesbian.” The lesbian, however, has rather dramatically re-appeared, as for instance in the new semi-arthouse neo-exploitation noir film Love Lies Bleeding, which evidences nary of trace of transgender ideation even amid all its sweatily pharma-enhanced and eventually Brobdingnagian sapphism. The film’s star, Kristen Stewart, recently expressed her desire to do “the gayest thing ever.” Considering friend-of-the-blog Blake Smith’s wise thesis on the distinction between “gay” and “queer,” however, the film was certainly as gay as it gets, but, even despite its giantess-porn climax, still somewhat less queer than the repro-heterosexual perversities of those last two Twilight films and their protracted passion-play spectacle of Bella/Stewart’s dangerous deflowering and lethal gravidity.

Shortly thereafter followed Blake’s polemic (co-authored with Taeho Kim) against the swallowing-up of gay male identity by queer theory. I mention it because this distinction will become relevant to the historicization of sexuality we are approaching in The Invisible College as we near the fin de siècle and its high and low modernist sequelae. For one thing, as queer theory’s own den mother Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick observed in Epistemology of the Closet, late-19th-century culture witnesses the beautiful boy succeeding domestic woman as the locus of literary sentimentality.

But the distinction between “gay” and “queer” may also be in development at the very same cultural moment, before “gay” itself is truly consolidated as an identity or culture. It’s possible that “queer” just is modernism proper. I will put it in terms of the authors we’re about to read: on the one hand, we might say that Wilde and Auden are gay, while Joyce and Lawrence are straight; on the other hand, we might just as well insist that Wilde and Joyce are queer, while Lawrence and Auden are not. I’ll develop the distinction as we go, but it has something to do with how much you believe that something called “nature” either exists or is worthy of respect by the artist. With allowances for each writer’s complexity, we might say that Wilde and Joyce would replace nature with art, while Lawrence and Auden caution against this for various reasons of their own.

The presence of E. M. Forster in the conversation, with his male lovers’ climactic flight to the greensward in Maurice, would make the distinction still clearer, for which see my essay on Forster’s novel.4 Lawrence, however, probably read Maurice in manuscript and modeled the phallic and naturalistic hetero-utopianism of Lady Chatterley’s Lover upon it, with Walt Whitman and Edward Carpenter in the background as further gay influences. Heterosexuality might well be posterior to homosexuality,5 while queerness, whether we like it or not, seeks to undo this very binary via inorganic agents like Wilde’s promiscuous aestheticism and Joyce’s pansexual textualism.

With Blake’s caution against my taste for binaries ringing in my ear, however, I note that Joyce’s encyclopedic fleshliness in Ulysses and Lawrence’s gnostic contempt for the merely natural in Women in Love complicate my neat division, as does Wilde’s incipient and Auden’s accomplished Christian faith—not to mention the paganism and mysticism Forster nervously celebrates from “The Story of a Panic” to A Passage to India.

In sum, I take the whole discussion to be proof of my opening gambit in founding The Invisible College: our most urgent political and social discourses of today, wherever we fall in our judgment of them, have their prehistory in the modern sequence of Romantic, realist, and modernist literature. This literature, then, should be our study.

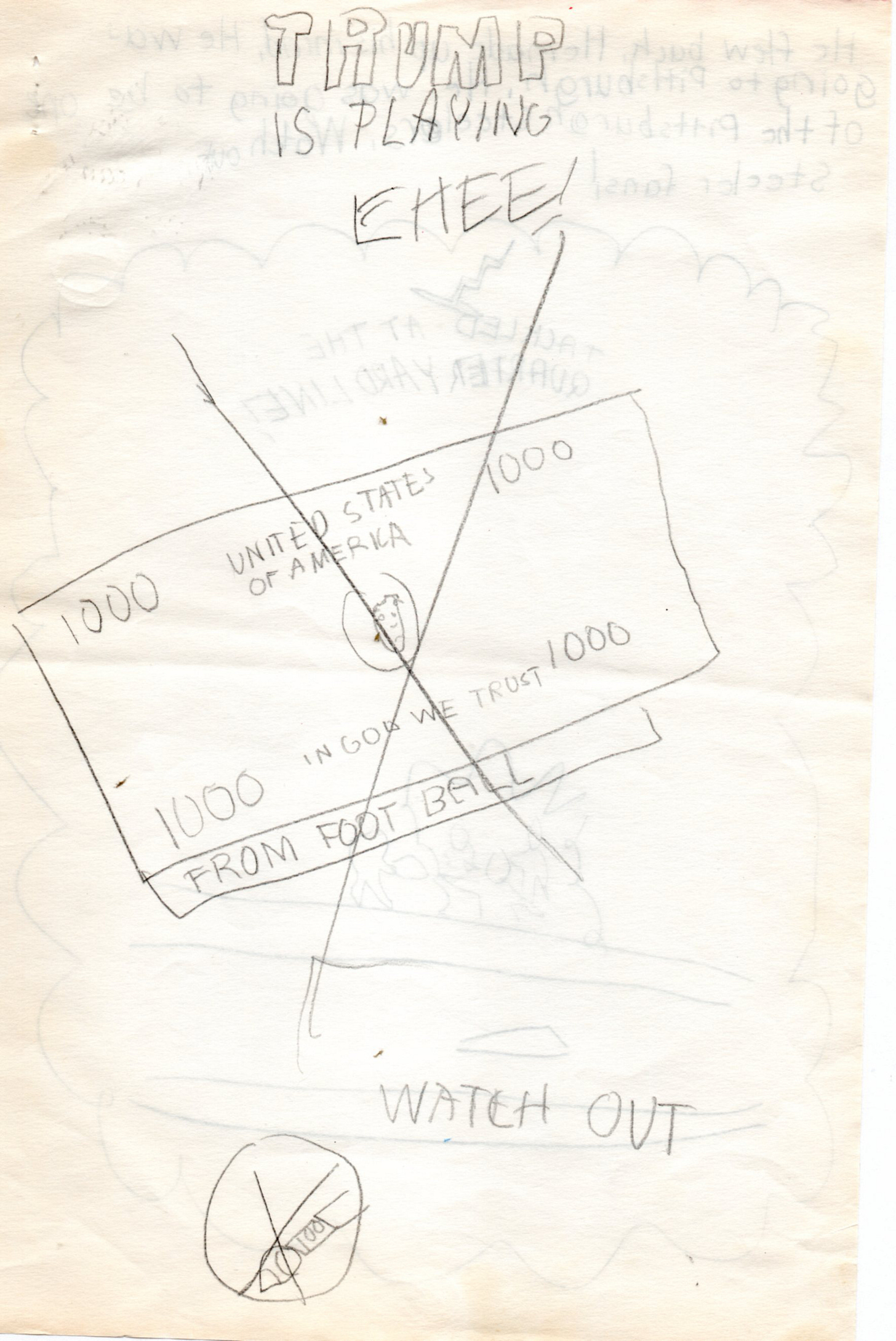

Synchronicity #3: The Lesser Trumps; or Juvenilia as Prophecy

Since that fateful descent down the golden elevator in June of 2015, I have been telling people that I started writing a novel about Donald Trump when I was a child, near the apex of his Reagan-era celebrity. I remembered very little about it, however, only that I’d done it. I’ve often wondered if there was anything vatic about it.

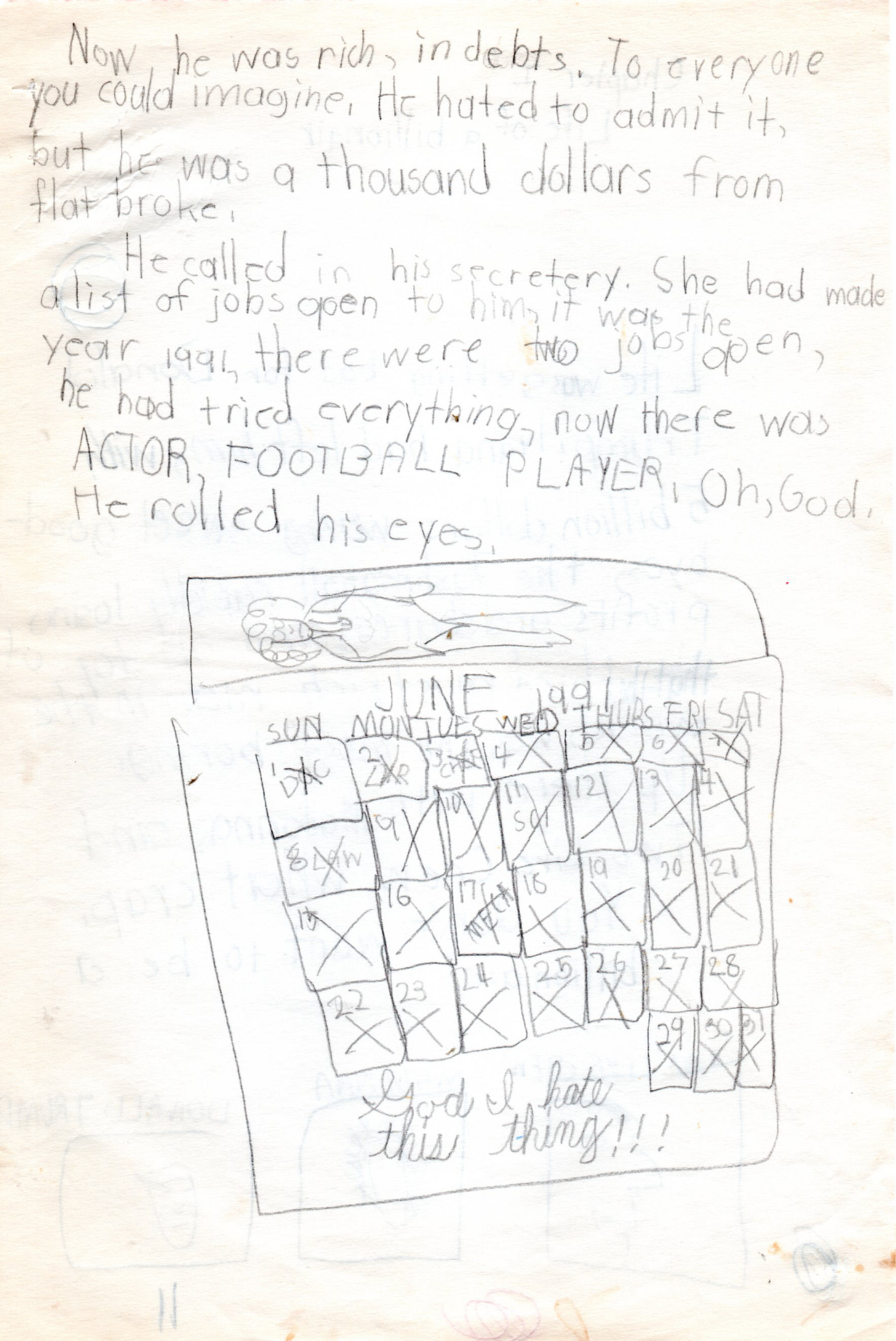

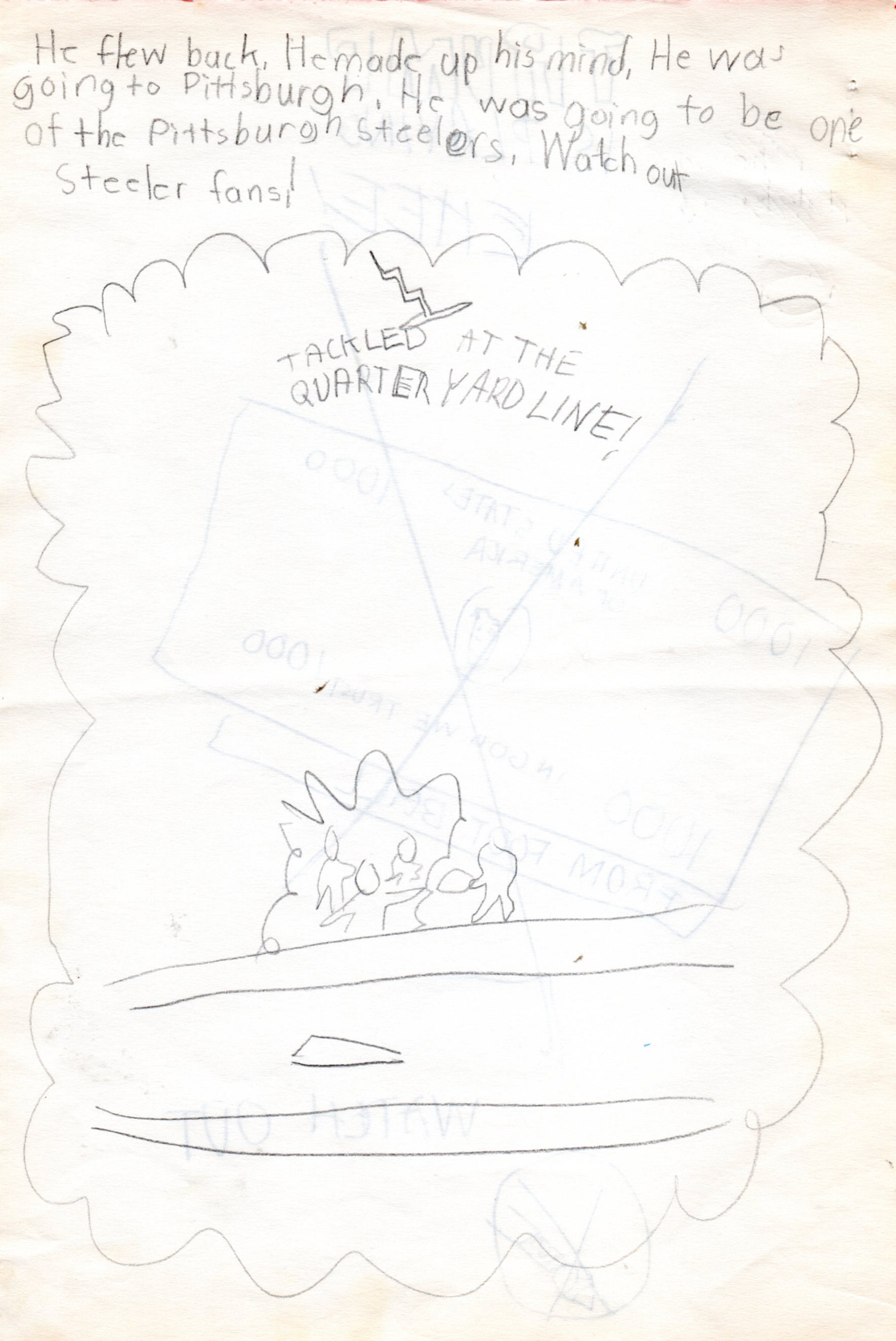

Thanks to my father, the manuscript has been recovered, and I offer it below. (My father suggested I restrict it to paid subscribers, but I thought its widespread dissemination a matter of democratic principle.) Internal evidence—the girlie calendar on page 2—suggests it was produced in June of 1991, exactly 24 years before the fateful candidacy, when I would have been nine years old.

The inciting idea seems to have been Trump’s widely reported financial difficulties. There followed my childish meditation on what such a man might do for money. Never an economic thinker, as we’ve seen, I didn’t then understand the distinction between wealth and cash on hand. As I’ve also never had the slightest conception of traditionally productive labor, professional football and filmmaking were my answers to the rich man’s dilemma. I apparently intended a survey of American popular culture—a great American novel, in fact—but as my youthful interjections of frustration with the project (“God I hate this thing,” “why am talking like that”) intimate, I understood that I did not yet possess the literary force to animate an epic like Major Arcana.

The extraordinary crudity and satirical nastiness of the whole production—even then I must have regarded it as a jeu d’esprit, the work of my left hand, as opposed to the more serious Superman and Batman comics I would have been drawing at the same time—suggests the deep-rooted sensibility, lower-middle-class to the core, my cultivated taste holds at bay. You can thank me for this later.

Is it vatic? You can say that I foresaw the hold Gone with the Wind would come to have on the Trump-attracted imagination, as attested here by Catherine Sulpizio. I leave you to interpret the thematic role played by Stanley Kubrick in the narrative. I will only say that I foresaw Trump’s ambition to compete on the same level as the masters of art, even if I did not see that he would triumph on this level—the first Aesthete-American President—in the cultural absence of such mavens as Kubrick. Please enjoy!

I’ve already heard about one or two typos. Even mainstream corporate fiction is riddled with these mistakes, so I’m sure an independently published work of 700+ pages can’t escape, no matter how carefully edited. Rest assured, I’m keeping a file—“Minor Errata in Major Arcana”—and will update the text eventually. In the meantime, you’ll want to own a first edition whose uncorrected errors will make it all the more valuable in future collector markets. On the value of such errata, I rest my case with the Pynchon of The Crying of Lot 49 for whom such “inverse rarities” unlocked the secrets of America and the universe.

This is not financial advice. I don’t even own any crypto—yet.

Despite the old Marxist slur that the petite bourgeoisie is inherently fascist, Noah’s riposte is not how a fascist would greet the news that egirls (some of them in the orbit of Substack occultists I started reading to research Major Arcana) have been added to the blockchain for investment. A fascist would roar, with old Uncle Ezra, “They have brought whores for Eleusis.” Needless to say, I disavow.

I am no longer an academic, and I never was in my soul, but in academia the shadow of one’s potential succession does fall over one. You may, therefore, take my meditation on the sexuality of this little canon (Wilde, Joyce, Lawrence, Forster, and—well, not so much Auden as Isherwood) as an extension of my Ph.D. advisor’s thinking, thinking of the exact sort Blake means to criticize, or apparently so. Consider this almost decade-old lecture rebuking Isherwood for his “sexual exceptionalism” to see what I mean. Its implicit Laschian left-conservatism saves the performance from mere queer-theory moralizing despite the opening invocations of Butler and of “homonormativity,” however—or at least I think it does. Similarly, a one-sentence summary of her judgment on Forster in her book on gender and modernism might be “Maurice is gay, but Howards End is queer,” with an implicit positive judgment on the former, not the latter, since she treats “queer” and “modernist” as synonyms not only with one another but also with “elitist.” Maurice, meanwhile, she judges “Forster’s most democratizing testament to queer masculinity,” almost the nicest thing she says about any modernist work in a survey of Lukácsian severity. As I am always saying, we do contain multitudes.

Such a statement will seem absurd to my conservative or IDW readers, the ones who lose their cool at any mention of “postmodernism” etc., but consider it this way: before the secularization of western culture, the proper fulfillment of one’s erotic duties was limited either to procreative sex or to celibacy. One’s inner and felt sense of desire was irrelevant, especially since such desire emerged from fallen nature. Whether one discharged this fallen desire illicitly, if one did, with a member of one’s own sex or with a member of the opposite sex was less damning than that one had discharged it at all. (Hence, for example, the definition of “sodomy” includes non-procreative acts between men and women.) That one’s inner and felt sense of desire might be both innate and legitimate on terms other than Christian sexual pessimism arguably first becomes visible with the definition of the homosexual and is only thereafter extended—as the norm—to the concept of heterosexuality by the class of psychological experts that succeeds the clergy as would-be masters of our desire. Hate “postmodernism” all you want, but sometimes the hegemonic term really is almost entirely constituted by the subaltern term it attempts not only to abject but also to expel.

DFW or DeLillo in his prime could write a great novel about Trump, although I’m not quite sure how you’d swing it. Re: fascism (of whose or of what kind I’ll leave to you to decide) I’m always thinking that someone should write the American equivalent of the sea of fertility, some abyssal nihilist account of the decay of the national angel through disastrous reincarnations from upwardly mobile citizen-prince in the 20th century to gooning groyper in our time.

always a delight to be discussed--I wouldn't posit gay-queer as a binary... as I have written on Substack in that piece complaining about Benjamin Moser, 'queer' has multiple meanings, one of which names the inherent uncanniness of sexuality per se in the way that it resists both our normative moral frameworks and our attempts to corral its slippery energies into cohering around even what we might take to be an anti-normative oppositional identity. In that sense Lawrence and Forster, for example, could be said to be both queer (exploring what's beyond, forbidden, excessive, chthonic, utopian, etc in sexuality) and trying to unqueer it (as prophets, like Whitman and Carpenter as you astutely say, of a new sexual order, liberated, happy, and so on)... it might be indeed interesting to think more about those tensions in their works and the similarities of the authors with the question of their 'sexual identity' (homo/heterosexuality) suspended (along with questions about, say, gender, feminism, etc, in their work), or at least not given analytic priority, focusing on their metaphysics of 'sex' alone to see more how they're playing the multiple and somewhat contradictory roles inherited from the 19th sex-reformers of both rebels and restorers... (Interestingly Lawrence was a big inspiration for gay writer/activist Larry Kramer who wrote the screenplay for Women in Love--which for me is a dreadful movie that reveals Lawrence to be, most of the time, a sort of drearily moralizing Ken Russell--but mileages will vary!)

As to Auden, well, he's homosexual but not gay in the sense of gay literature--his openly gay verse is scant and hardly circulated, although he was part of a closeted network and promoted other such authors such as a young Ashbery (or as Paul Franz has recommended to me, the brilliant Alan Ansen). Wilde too was a married man with children. They were neither of them gay in the contemporary sense, although of course they inspired much of its sensibility (even as much of it is also constructed in opposition to their elitist, Paterian, Romish, sneering, tinkering, arch Great Uncle Arthur silliness)... Lawrence is perhaps closer, backward from Whitman and forward to Kramer, to the modern gay spirit, if we want to keep turning the labels inside-out.

At any rate, it's not a question of setting 'queer' up against 'gay' or anything else. 'Queer' being what it is, it is not capable of being instantiated in an identity, author, text, tendency, etc, except in a self-negating ironic way (what has happened with institutional and academic queerness). Everyone, as a conditional of being a sexual (that is, psychic) agent is queer; no one, as the bearer of any cohrently avowable position, is queer. It oughn't to be a question--which is to say it often is one--of finding that this or that author is excitingly or disturbingly 'queer' in opposition to something 'normative' or 'homonormative', only of tracing, hopefully with the pleasure of wonder along with the occasional dizzy spells of bewildered horror, how such queer stuff as sexuality grounds and undoes the selves, roles, orders etc we cannot make, maintain, or transmit out of anything else...