A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I published “Against Novels,” chapter three of Part Three of my serialized novel for paid subscribers, Major Arcana. We left Ash del Greco, a teen of the last decade, on the threshold of high school after her first stunned encounter with the revolutionary gnostic superhero comics of Simon Magnus, whom, she now suspects, may be her father. In the next chapter, coming Wednesday, she will meet Ari Alterhaus, and they—“they” together, and eventually “they” singly—will form a cult of two that will change everything in their world. (I will repeat here for new readers what I have already described as Part Three’s guiding question: what would a banned-book YA novel about gender and the internet look like if it were written by a consortium of Dostoevsky, DeLillo, and the heresiarchs of Uqbar?) Please subscribe!

Also, as part of a—what? “roundtable”? “colloquium”? is there a non-annoying word for this?—with Blake Smith, Dan Oppenheimer, and Paul Franz, I’ll be dropping a piece this week about the 30th-anniversary edition of Dave Hickey’s The Invisible Dragon: Essays on Beauty and Other Matters. Blake’s piece, “Dave Hickey, That Queer,” is already up (I haven’t read it yet, but I’m sure it’s good), so please look for mine in the next few days.

Today’s post comes in two parts: the first, a sort of sequel to last week’s entry, pursues further the theme of literature and literary theory’s relationship to revolutionary political violence; the second, reprised from my Tumblr, is a requested list of my favorite essays and essay collections in the genre of literary criticism. (You might want to follow my Tumblr since that’s where readers send in questions, prompting me for everything from my favorite theory of art to my thoughts on Akira Kurosawa to my views on MFA programs. Readers also berate me, insult me, and rant at me, but, while I read it all, I don’t post every example of that type of thing.) As always, here on Substack, the real action is in the footnotes. Please enjoy!

The Heart’s Grown Brutal: Culture, Barbarism, and the Education of Adults

I saw a minor conflict on social media over a post by someone I won’t quote by name—a might-as-well-be-anonymous Ph.D. student with the usual panoply of such a person’s opinions (I’m sure I held them myself in earlier days)—who wrote:

Always weird to me that there are educated adults who have not yet accepted that, as Jameson said, “the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and terror.” I don’t know how to begin a serious conversation about the value and use of literature without that basic assumption.

I’m trying to think my way back into the moment in my life when I thought this truly meant something. I once did. Fredric Jameson1 had the observation from Walter Benjamin, from the last thing Benjamin ever wrote, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” on the eve of the suicide he committed to avoid being subject to genocide.

Benjamin in extremis had, then, earned the insight: an insight turning certain Hegelian and Nietzschean presuppositions—that culture, broadly speaking, is a flower whose roots are nourished by the blood running from history’s slaughter-bench—on their heads, this as Hegel’s and Nietzsche’s putative heirs conducted their reign of terror against several different kinds of people who might be described as Benjamin’s people, to include Benjamin himself.

To historians who wish to relive an era, Fustel de Coulanges recommends that they blot out everything they know about the later course of history. There is no better way of characterising the method with which historical materialism has broken. It is a process of empathy whose origin is the indolence of the heart, acedia, which despairs of grasping and holding the genuine historical image as it flares up briefly. Among medieval theologians it was regarded as the root cause of sadness. Flaubert, who was familiar with it, wrote: ‘Peu de gens devineront combien il a fallu être triste pour ressusciter Carthage.’ [‘Few will be able to guess how sad one had to be in order to resuscitate Carthage.’] The nature of this sadness stands out more clearly if one asks with whom the adherents of historicism actually empathize. The answer is inevitable: with the victor. And all rulers are the heirs of those who conquered before them. Hence, empathy with the victor invariably benefits the rulers. Historical materialists know what that means. Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which the present rulers step over those who are lying prostrate. According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along in the procession. They are called cultural treasures, and a historical materialist views them with cautious detachment. For without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.

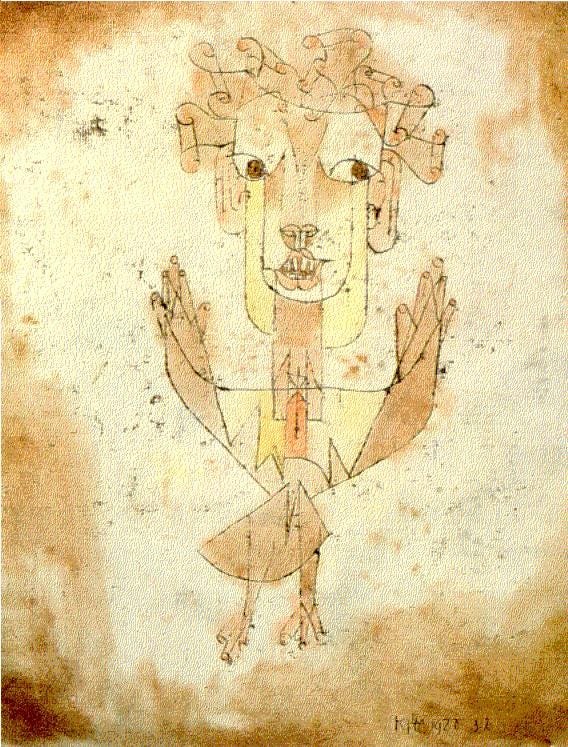

The problem is that the first version of the insight, the insight “standing on its feet,” as it were, does entail a piece of wisdom we might act on, while the transvalued version does not quite: create beauty even in the face of the worst, because the worst is inevitable, is in the very nature of things. And who knows? In the long run, the beauty might outrun the terror, perhaps in the last instance, even if you won’t be there to see it. The fate of Benjamin’s own text illustrates the cultural process the text itself decries: rescued by Hannah Arendt, it has been canonized as a lyric of its century, less a set of theses than, no less than Celan’s,2 a kind of death fugue. The more beautiful the iconoclastic testament, the likelier it is to become an icon. What kind of cultural treasure is this denunciation of treasures, exactly?

The point has not been pressed enough in cultural criticism, for the second version of the insight—not that culture redeems barbarism, but that barbarism condemns culture3—would only mean anything if you, you yourself, the addressee of this discourse, the artist or the lover of art, could do anything about the barbarism, anything, that is, that wouldn’t look like more barbarism. (This impossibility is why Adorno said it was obscene to write poetry after Auschwitz. Benjamin would have told him it was obscene before, too.) Benjamin’s dying testament, for all its unnerving power, doesn’t quite pass this test; we know now the impossibility of its hope-against-hope that The Revolution might be the clock-stopping moment when transcendence penetrates immanence—the timeless time when, as a contemporary of Benjamin’s (a Christian rather than a Jew, a reactionary rather than a revolutionary: so widespread is this hope) put it, “the fire and the rose are one.”

As poetry, it’s sublime, incomparable, but as a set of practical recommendations to the political actor, its Year-Zero politics would be those of Pol Pot, a curious idolatry of this-worldly terror vainly calling itself Messianic. Such an error has subtended many a crusade, many a massacre, in the name of many a god.

A historical materialist cannot do without the notion of a present which is not a transition, but in which time stands still and has come to a stop. For this notion defines the present in which he himself is writing history. Historicism gives the ‘eternal’ image of the past; historical materialism supplies a unique experience with the past. The historical materialist leaves it to others to be drained by the whore called ‘Once upon a time’ in historicism’s bordello. He remains in control of his powers, man enough to blast open the continuum of history.

What happens when this ideal of manhood-as-apocalyptic-virility, mandated by universal justice, is distributed to everyone else? I asked this question in a short story called “White Girl.” If you actually take literally the politics promoted by radicals—if you really believe both that every instance and every outcome of human hierarchy are inherently unjust, and, in corollary, that hierarchy per se is an immanently remediable condition among human beings, then you are obligated to take revolutionary action.

She said, “That’s what people don’t get. It’s not what you think, it’s not even what you do. It’s who you are in the system. If you are on the oppressive side in the system, then you oppress just by being what you are. Since the system makes you what you are, you can’t be anything else unless the system is destroyed. For the system to be destroyed, what is must be destroyed.”

She didn’t take the last step, but I thought I heard it, in my head, in her voice, though her lips weren’t moving, in her weird language made of all she’d read mixed together: “Therefore, white girl, you oppress by being and must be no more.”4

The girl in the story believes it. It’s not a story without action, after all: this, her climactic murder of her father, is the consequence in narrative craft of the relation between culture and barbarism.

But you don’t believe it. You say you believe it to get ahead in the hierarchies of the institutions controlled by the left. Sometimes you even go so far as to cheer on others who commit the atrocities you are too weak and cowardly to commit yourself, because you believe (or say you believe) such atrocities may in some way, you don’t know in what way, realize the image of utopia you have been sold by the mountebanks of academe and by the votaries of redemptive violence. As Yeats wrote,

We had fed the heart on fantasies, The heart’s grown brutal from the fare, More substance in our enmities Than in our love...

But even then, you don’t believe it. You don’t believe it because it’s not true: you know somewhere inside of you that the arrival or the re-arrival of the Messiah is not for us to accomplish on earth by force of arms. Because it’s not true, the first thing you should do is to treasure whatever of beauty and love you can find or make in this world. The second thing you should do, especially if you are an “educated adult,” is to ignore the priests of a false religion who would, in the name of a justice that is by the very nature of its absoluteness not available here or to us, destroy not only the evil but also the good we’ve been given.

We should criticize Benjamin carefully, even gently, with fear and trembling, with our hearts in our throats, in sympathy with the desperation that brought him to that pass, to those words, to such a severe redaction of the two traditions he prized as he watched his world end. The middle-class radical, however—Jameson, with his lifetime of tenure, for example—the bureaucrat who aestheticizes “blood, torture, death, and terror” in the guise of forbidding aesthetics to the rest of us for our own good: him we may simply dismiss.

Crit List: My Favorite Critical Essays and Collections

A reader on Tumblr requested my “favorite essays/collections of literary criticism.” I posted the answer there earlier this week, but thought I’d also share it here for Substack subscribers.5 (The order, by the way, is roughly chronological. I did this by instinct or impulse. We hate in others what we fear in ourselves: I rail against the historicists, and yet—or because—my mind tends to take the same shape as theirs.)

Some favorite single essays:

Percy Bysshe Shelley, “A Defence of Poetry”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, “The Poet”

Herman Melville, “Hawthorne and His Mosses”

Matthew Arnold, “The Function of Criticism at the Present Time”

Henry James, “The Art of Fiction”

Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny”

Walter Benjamin, “Franz Kafka: On the Tenth Anniversary of His Death”

T. S. Eliot, “Tradition and the Individual Talent”

Viktor Shklovsky, “Art as Technique”

Mikhail Bakhtin, “Epic and Novel”

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, “In Praise of Shadows”

G. Wilson Knight, “The Embassy of Death: An Essay on Hamlet”

Simone Weil, “The Iliad, or, The Poem of Force”

Jorge Luis Borges, “Kafka and His Precursors”

Ralph Ellison, “The World and the Jug”

James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel”

Leslie Fiedler, “The Middle Against Both Ends”

Iris Murdoch, “The Sublime and the Beautiful Revisited”

Flannery O’Connor, “Some Aspects of the Grotesque in Southern Fiction”

Gilles Deleuze, “On the Superiority of Anglo-American Literature”

George Steiner, “A Reading Against Shakespeare”

Derek Walcott, “The Antilles: Fragments of Epic Memory”

Toni Morrison, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature”

Louise Glück, “Education of a Poet”

Camille Paglia, “Junk Bonds and Corporate Raiders: Academe in the Hour of the Wolf”

Michael W. Clune, “Bernhard’s Way”

Some favorite collections:

Samuel Johnson, Selected Essays

Oscar Wilde, Intentions

Virginia Woolf, The Common Reader

D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature

George Orwell, All Art Is Propaganda

Susan Sontag, Against Interpretation

Kenneth Rexroth, Classics Revisited

Guy Davenport, The Geography of the Imagination

Cynthia Ozick, Art and Ardor

V. S. Pritchett, Complete Collected Essays

Gore Vidal, United States

Joyce Carol Oates, The Faith of a Writer

Tom Paulin, Minotaur

J. M. Coetzee, Stranger Shores

Michael Wood, Children of Silence

James Wood, The Broken Estate

Edward Said, Reflections on Exile

Gabriel Josipovici, The Singer on the Shore

Clive James, Cultural Amnesia

William Giraldi, American Audacity

The specific quotation is from Jameson’s Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. The idea is treated with an unendurable theoretical rigor, however, in his pre-Postmodernism methodological summa, The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act. I can’t promise to have understood this recondite volume, but its thesis, to the best of my recollection, goes like this: while literature or culture more broadly has been humanity’s way of reaching toward a utopian horizon, its aspiration has always been compromised by its origin in class society, with such a society’s decidedly non-utopian inequalities. The Marxist critic, then, cannot only honor literature’s utopian impulse but also must recover the brutality literature represses in the “political unconscious” of the title. The point of such a project is to form an intellectual basis for the real utopia that only Marxist revolution is able bring about: the end of class society. Literature must be liquidated in and by Marxism, because Marxism will be and therefore always already was the deep truth of literature’s ineffectual yearning.

Jameson explicitly appropriates and reverses Northrop Frye’s liberal defense of literature’s autonomy from history that I quoted last week, because such a defense, which leaves our utopian aspiration permanently utopian, rules out Marxism’s claim to be the sole science of utopia’s materialization. (Pace Eric Voeglin, perhaps not every left-of-center thinker wants to “immanentize the eschaton,” but Jameson really does.)

More interesting to me, however, is the affect rather than the substance of Jameson’s argument. The Political Unconscious, a compendium of pitilessly long and jargon-choked sentences in the Teutonic style, is ironically remembered for two crisp slogans you could fit on a protest sign: “Always historicize!” and “History is what hurts.” The counsel that, to bring about a better world, we must ascetically dwell in blood, torture, terror, and pain—that every imaginative attempt to transcend blood, torture, terror, and pain must be rebuked as naive humanism from a posture of olympian scientific sophistication—well, I wonder: how could this, when reduced to terms that an undergraduate can comprehend, not produce two whole generations of humanities students who believe in terror as an instrument of revolutionary policy? Always historicize; history is what hurts. The more you make it hurt, then, the more history you will make.

See also my riposte to Jameson’s beautiful and terrifying essay on Ulysses, where I explicitly defend the petit-bourgeois class basis of modern literature as a potential universal humanism, albeit a universal humanism that forestalls Marxism’s apocalyptic sublime. If the petite bourgeoisie is, in Marx and Engels’s words, “try[ing] to roll back the wheel of history,” then it is cognate with “the Jew” in the imagination of the left-wing anti-Semite, who may in this respect be compared to the Christian and the Muslim anti-Semite. (Ironically, this insight was available to Jameson—while we’re charting academic genealogies, the supervisor of his doctoral dissertation was Erich Auerbach, not Northrop Frye—but he chose not to avail himself.) For more on this possibility, see Adam Kirsch and Zohar Atkins. Speaking of Kirsch, it is never a bad time, though it may alas be too late, to reread his essay, “To Hold in a Single Thought Reality and Justice: Yeats, Pound, Auden, and the Modernist Ideal.” I should have included it in my list of favorite critical essays below, though I think it undersells Yeats’s ironies and antinomies on its way to (possibly) overpraising Auden.

Almost the last controversy I remember observing during the mid-2000s period when I participated in the radical left wing of the then-active literary blogosphere was about Celan’s possible Zionism. The essay making the “charge” is, interestingly, still up after all these years. The author was a British Marxist and anti-Zionist writer (he may still be, but he now shuns publicity). The poem of Celan’s that irritated him, “Denk dir,” was written and published just after the 1967 war. I was unable and remain unable to weigh in; Celan is untranslatable, I don’t read German, and, anyway, I understand the whole point of Celan to be that he didn’t write German exactly, which one must read German better than the Germans to appreciate. Here is the poem as given in the essay, in Michael Hamburger’s translation:

THINK OF IT Think of it: the bog soldier of Massada teaches himself home, most inextinguishably, against every barb in the wire. Think of it: the eyeless with no shape lead you free through the tumult, you grow stronger and stronger. Think of it: your own hand has held this bit of habitable earth, suffered up again into life. Think of it: this came towards me name-awake, hand-awake for ever, from the unburiable.

I don’t read German, but I do know that “home” in the third line is “Heimat” in the original, not a word Celan could use in such a context without even a hint of irony. And even in English, “uburiable” has negative resonances as well as positive: in the context of debates over the ethical limit of statecraft, one thinks only of Polynices. The injunction in the title, wavering between an exhortation to marvel and an invitation to wonder, should really say it all. My point is not to approve or disapprove of Celan’s approval or disapproval of Zionism—as I said, I cannot read Celan at all, I cannot even begin—but to restore our proper appreciation of poetry’s polysemy. Deliberate polysemy in what is meant to be a political slogan is abusive, obscene—e.g., to take a purely random example, “from the river to the sea,” with its exoteric plea for ethnically and religiously pluralist democracy and its just barely deniable esoteric call to extermination—but what is abusive and obscene in a poem is rather deliberate polysemy’s absence. A poem is not a political slogan; it is, as Yeats wrote, a quarrel with ourselves.

I sometimes wonder if the moral sublimity and extremity of Frankfurt School and related aesthetics don’t conceal something more banal: the inability to appreciate any art at all unless it can somehow be understood as verisimilitude. I saw an incredibly trivial example recently, but its very triviality, its distance from Stalin and the Holocaust, may help to emphasize the issue. For some reason, The Atlantic ran a testimonial last month from a critic who finally learned to appreciate Garfield. (I like the idea that this is a solemn duty, that not appreciating Garfield is like not appreciating Guernica. For my part, I’ve always appreciated Garfield.) How did our critic do it? By coming to understand Garfield the characer as, at bottom, a naturalistic depiction of a domestic cat. Now in response to this, we might enumerate all the ways in which Garfield is not a naturalistic depiction of a domestic cat (he’s bipedal, he subsists on lasagna, he’s canonically literate, he has an articulate inner monologue…), but this would be missing the point. The point is that the pleasure of Garfield lies in this cat’s literally outsized personality, not in his resemblance to any real animal. He is an exaggerated depiction-for-children of a charmingly louche and lazy glutton, a cynical sybarite in a workaday world; he’s not a cat, but Falstaff for eight-year-olds. Is it too much to say that needing to find a normal cat in Garfield may just be a lowbrow and apolitical version of how Adorno and Jameson, if not Benjamin, read the works of the western canon? Jonathan Franzen would order us to imagine how many birds Garfield has killed!

And yet Hamilton Nolan, of Gawker renown, if “renown” is the word, defends the idealism of radical youth:

Older people who have lived through more things and read more books often mock this moral clarity as the product of childish, unsophisticated minds. Yet that judgment is itself a product of fear, of weakness, of the very human need to justify ourselves to ourselves. In fact, the moral clarity of youth is priceless treasure. It is the fuel that propels action towards justice. It is untainted idealism, which is a necessary ingredient for any movement that aspires to change the world for the better. The very things that older people find repellent about young people’s political attitudes—the certainty, the self-righteousness, the impatience with any delays—are the same things that we should welcome. They are the things that older people, with all of their knowledge, often lose.

Which I might agree with if radical youth were preaching a doctrine of peace and love that, even if naive, points toward ideals we would indeed be not only foolish but cruel to disparage. This is not what’s happening now, however, not what the children of Jameson are chanting in the streets. They don’t sound like starry-eyed hippies with impossible dreams—I might admire them if they did—but like hard-bitten Machiavellians, cooly demanding the “necessary murder” as they claim we mustn’t set ethical limits to the armed struggle of the oppressed. They aren’t tender youths; they’re old before their time, already shriveled in their souls by compromising what ought to be youth’s lyricism. I think of Bob Dylan’s lines about abandoning his own youthful dream of revolution: “Ah, but I was so much older then / I’m younger than that now.”

As the reference suggests, they are children of an older lineage than Jameson’s though, older even than Marx. I come by the phrase “necessary murder” from Auden by way of Orwell. I’ve done my duty as a critic of Orwell’s occasional over-simplifications in these electronic pages, so let me give him his due yet again, even at the risk of stating the obvious, for having had the poet-revolutionary’s number long ago in “Inside the Whale”:

But notice the phrase ‘necessary murder’ [in Auden’s poem “Spain”]. It could only be written by a person to whom murder is at most a word. Personally I would not speak so lightly of murder. It so happens that I have seen the bodies of numbers of murdered men — I don't mean killed in battle, I mean murdered. Therefore I have some conception of what murder means — the terror, the hatred, the howling relatives, the post-mortems, the blood, the smells. To me, murder is something to be avoided. So it is to any ordinary person. The Hitlers and Stalins find murder necessary, but they don't advertise their callousness, and they don't speak of it as murder; it is ‘liquidation’, ‘elimination’, or some other soothing phrase. Mr Auden's brand of amoralism is only possible, if you are the kind of person who is always somewhere else when the trigger is pulled. So much of left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don't even know that fire is hot.

I will grant that this “brand of amoralism” is not limited to radicals, however, and applies to every armchair warrior of every political persuasion—hence my advice to artists and humanistic intellectuals to decline to advocate political violence in any cause, or at least not to lend their artistic and humanistic authority to such interventions even where the citizen’s duty may require making a stand.

Auden would later recant, of course, mutilating the best of his political poems, “September 1, 1939,” due to the cheap if unforgettable eloquence of some of its sloganeering: “Those to whom evil is done / Do evil in return,” as if this facile arithmetic could explain the infinitude of human perversity disclosed between 1939 and 1945. He even canceled the poem’s most famous line, “We must love one another or die.” This redaction goes too far, however, because we must, and we must also, as his first revision had it, “love one another and die”—just not in the way meant by the metaphysicians of The Revolution.

Many of these essays and collections have been discussed either briefly or at length in the johnpistelli.com archive. Please use the Review Index or the search bar. Given the subtext of today’s and last week’s posts, and because I saw a social media post by a writer anguished over her admiration for both Cynthia Ozick and Edward Said though the former deeply despised the latter (and, I assume, vice versa), I will draw your attention here and here for my own literary understanding of their political conflict and for a sense of why both are on my own list of favorites. I think of the impasse between the golem and the heroine in The Puttermesser Papers: “The politics of Paradise is no longer politics,” the golem tells the heroine, to which she replies, “The politics of Paradise is no longer Paradise.” Everyone named in the above essay, and its author, are torn apart by this contradiction.

I was telling a friend what a relief it is to realize that I don't need to stop believing what I believe simply because the youth don't believe it. He said that's how you become right wing. I said so what?

Maybe it's my duty in the dialectic to be the obstacle that is overcome. Seems absurd to roll over and show your belly simply because someone says you're now the enemy instead of the vanguard

I tend to have a less cynical but maybe grimmer view of that side of the left-much less of it is conscious than we realize, I think. (A lot of this goes for parts of the right as well, although this isn’t relevant to the discussion. It might just be a characteristic of the type of person in question.) I’m not sure I completely agree that Jamison is useless, although of course, I concur with your conclusion that he is as politics. Part of the fire and the rose (which like the fall I understand as something within human cognition and maybe just is what I was glossing as metamodernism recently) is recognizing and understanding the horror baked into the world as tragedy without believing that its very existence annuls all beauty.