A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week, in case you missed it, I posted my “June Books” round-up on Friday and “Cosmic Poetics,” a pod conversation with poet Emmalea Russo, on Monday—and, of course, “A Love Supreme” on Wednesday, the latest chapter in both text and audio formats of my serialized novel for paid subscribers, Major Arcana. “A Love Supreme” continues the beautiful and terrible love story of writer Simon Magnus and editor Ellen Chandler as they revolutionize the American comic book at the end of the American century. This coming Wednesday, we will rejoin the aniconic communist artist Marco Cohen for a philosophical dispute with a drawing teacher and a fateful encounter with a classroom model as he moves unwittingly toward his own tragic entanglement in Simon Magnus’s destiny. Please subscribe today!

(By the way, since some of you must be wondering: we are now about a third of the way through Major Arcana. There are 50 chapters, counting the prologue and epilogue. The serial will conclude in March 2024.)

I am currently traveling and writing in haste, so I provide below in lieu of an essay three fragments, two of which (about Dickinson and Paglia/Sontag) appeared on Tumblr this week or last for those of you who don’t follow me over there,1 and the third of which, narcissistically concerning gender politics and juvenilia, is both original and intriguing. I will post in reverse order so you don’t have to wait for the most sensational material—though do, please, kindly stop for Emily. Please enjoy!

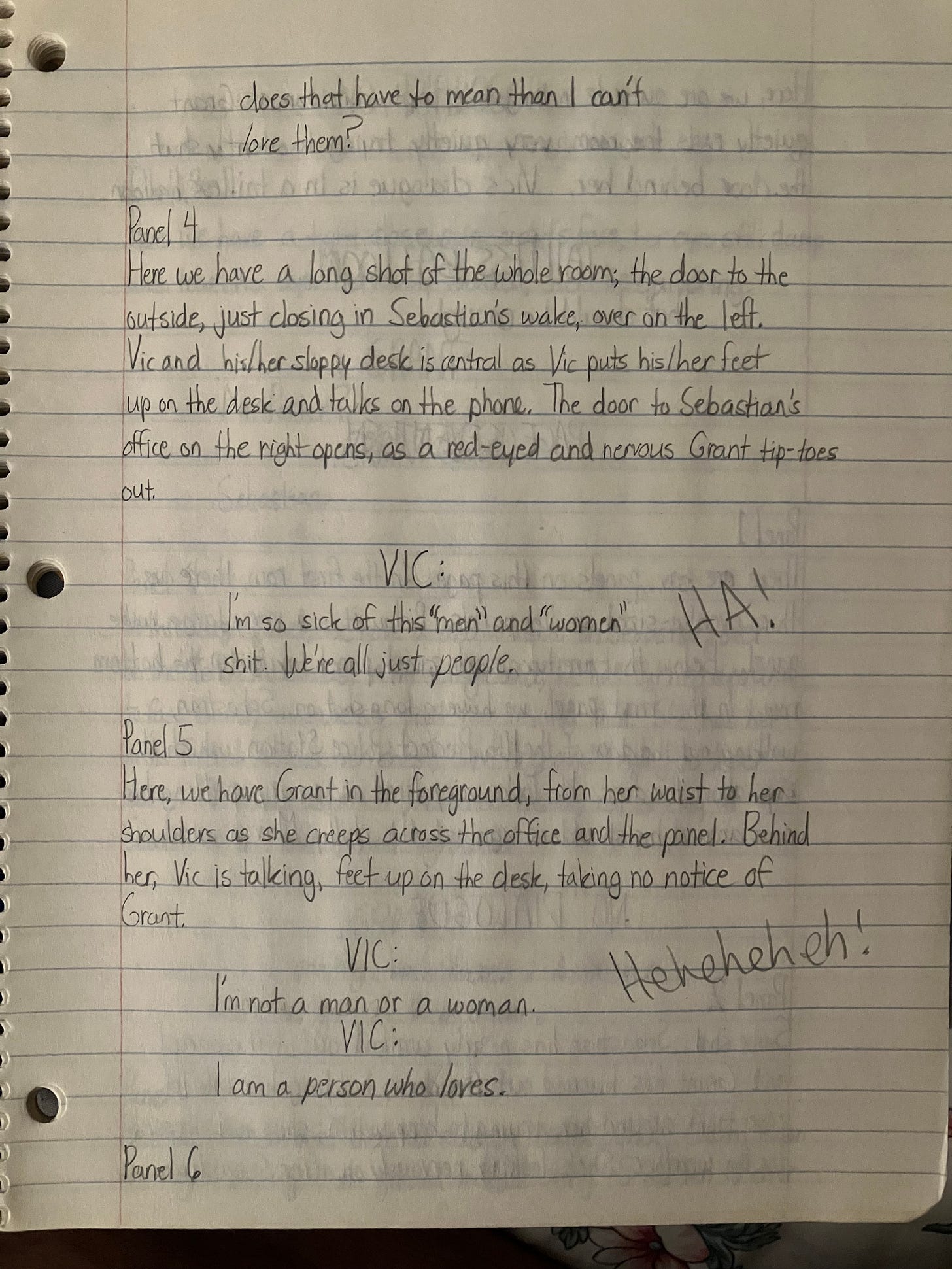

“A Person Who Loves”: From an Old Notebook

En famille for the holiday, I was going through some old papers and found two notebooks I filled in about the spring of 1997 when I was a freshman in high school. They contain a script for a 96-page graphic novel about a serial killer stalking a futuristic pseudo-utopia, even as the stereotypically rumpled male detective in charge of the case is sleeping with the airless polity’s silver-maned female dictator. In the event, though I don’t plan to reread too much of this crap, I believe a robot or android, also the dictator’s lover, committed the crimes (something about the dehumanization of modern life etc.).

My feeble detective story—never a genre that did much for me on the page, not unless incarnated in Chandler’s “slumming angel” prose—was more or less an excuse for a subplot about the city’s gender-radical youth, a group of friends centered on the genderless, charismatic, and even prophetic Vic. Vic, alas, later falls beneath the killer’s blade—I grasp the unpleasant political implication of this gesture now, but I was 14 at the time, so give me a break. (I surely ought to burn the notebooks.)

Vic’s dialogue in the photo above is tolerable only because I mostly swiped those lines from a letter a girl wrote to me about why we couldn’t date. Partly in response to the letter, I wrote the graphic novel for her; you can see her annotations, chortling at my plagiarism, in the margin. We eventually dated. Once she read me the gay sex scene in The Mysteries of Pittsburgh over the phone. I still don’t entirely know what that meant, but it would itself be a good scene in a novel. 1997!

I bring this adolescent ludicrousness forward only as evidence for both the advocates and the adversaries of the politics of the present: they were the politics of the past, too. Moreover, even if you find Major Arcana’s subject matter or my handling thereof untoward, I have at least been thinking about it, even if wrongthinking about it, for a very long time.

Moralist vs. Aesthete: Notes Toward Sontag and Paglia

Proposed in response to the viral recirculation of a video on the Paglia/Sontag feud: what we really need is a book in the style of Craig Seligman’s Sontag and Kael: Opposites Attract Me2 about Sontag and Paglia.3

I thought Deborah Nelson’s Tough Enough—which I liked—should have ended with a Paglia chapter. The fact that it didn’t, and for what I take to be political reasons, suggests why Paglia has the upper hand in my view: she’s not going to be as easily recuperated by the institutions while she’s alive. It’s hard to imagine Paglia earning the admiration of a consummate professional like Merve Emre. Which is ironic, because Sontag proudly never taught and expressed only bitter contempt for academia while she was alive, while Paglia has faithfully taught for pretty much her whole adult life, if at a wary art-school distance from official academe. (Sontag was good at finding people, even countesses, who would pay her bills; Paglia perhaps not so much, or perhaps, to give her more credit, she regards herself as having a vocation.)

Politically, Sontag was always on the right side of bien-pensance, which I find slightly contemptible; people are allowed to change their minds, but still, if she’d maintained the political views she held in the ’60s into the ’90s then she would have been on the Michael Parenti side of Yugoslavia (or, conversely, her ’90s views in the ’60s would have put her on Updike’s, Ellison’s, and Nabokov’s side of Vietnam).

On the other hand, Paglia was and remains too credulous about pop culture, and Sontag’s later turn against it—if at times too much in the style of what Kael called the “Come Dressed as the Sick Soul of Europe Party”—was basically right. Almost her last act on earth was to canonize Bolaño, while Paglia was claiming George Lucas as our greatest living artist.

Paglia’s historical scope and emotional register are broader, and for this she’ll always have my heart; Sontag couldn’t have written a Paterian prose-poem in honor of the bust of Nefertiti or of a Tamara de Lempicka painting. But Sontag probably was more politically sophisticated, and the moral conscience that mortified and tormented her aestheticism created tremendous drama, and for this she will never lose my admiration; Paglia couldn’t have issued the prophetic injunctions of Illness as Metaphor or On Photography.

Hilariously but predictably, the moralist Sontag was apparently bad news as a friend, lover, or family member, if gossip and biography are to be believed, while the aesthete Paglia is by all accounts a perfectly kind person in private life.

(When dealing with moralists, you should always bear in mind this line from “The Soul of Man Under Socialism”: “One is absolutely sickened, not by the crimes that the wicked have committed, but by the punishments that the good have inflicted.” When dealing with aesthetes, you should always bear in mind Basil Hallward’s charge against Lord Henry Wotton: “You never say a moral thing, and you never do a wrong thing.”)

Paglia lived one side of the binary dividing them to the full, every inch the diva dancing a step of Apollonian precision even in Dionysian frenzy, whereas Sontag allowed—or couldn’t have avoided it if she’d tried—Athens and Jerusalem, never mind Apollo and Dionysus, to go to war inside her mind. In that sense, they’re not an equal match. I probably love Paglia more as a writer—that is, I love the spectacle she creates on the page—whereas what I love about Sontag, not that she didn’t write many unforgettable sentences, is the exemplary tragicomedy of the life of her mind.

Those are some notes toward the book we need.4

“Full Music”: An Emily Dickinson Primer

Since I attended the Art of Darkness podcast live show on Fitzgerald a month ago, they’ve since released two more episodes, the latest being “Emily Dickinson’s Immolation in White.” This reminded me that an anon wrote to me on Tumblr two weeks ago requesting a primer on Dickinson. Stipulating that I am not a scholar of the poet—though a friend of mine is—I have taught her work enough over the years, if mostly out of anthologies, to provide at least some introductory hints, which may also be useful to Substack readers, as follows:

If you start around minute 38 in this video lecture from an Intro to Lit course, I explicate “I Heard a Fly Buzz—When I Died” as part of a constellation with other poems by Gerard Manley Hopkins and Wallace Stevens. It should suggest some of her general virtues.

There’s a very slim volume edited by Joyce Carol Oates, The Essential Emily Dickinson, that collects her most famous poems, if not necessarily her best (I haven’t read every poem myself; it’s a large oeuvre). I don’t know if it’s a good critical introduction, but Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson—another slim volume—is a classic of poet’s criticism, liberated from academic constraint; I wrote about it here. On a more introductory note, here’s a slide on Dickinson’s poetics I made for an American Lit survey course:

Why do I love her? If for nothing else, she’s a master of rhythm. With a not-necessarily promising instrument—hymn meter—she can play any note. One of my favorites in this vein is “He Fumbles at Your Soul,” about God or a favorite poet or a gifted preacher or even a lover. Read it out loud a couple of times. And then there is her conceptual daringness—stressed by Harold Bloom in his essay on her work in The Western Canon—a Blakean counter-Christianity sly and subtle, as in the list of possible meanings for “he” in the poem just above, but sometimes wittily self-mythologizing, as in the beloved “Because I Could Not Stop for Death,” which I had to memorize in middle school (I kept calling Death “she” during my recitation because I was then, at age 13, totally immersed in Neil Gaiman’s Sandman), or the more explicit “The Bible Is an Antique Volume—,” not to mention her counter-Romantic sense of nature’s existential menace as well as its generative beauty, as in “A Narrow Fellow in the Grass.” Finally, I think of her palpable, alluringly vague eroticism—emphasized by Paglia in Sexual Personae, with perhaps an excessive focus on the Sadean—as in “I Started Early—Took My Dog—” Overall, the vision—the visitation—of an extraordinarily original sensibility arises from her poems.

I unashamedly use Tumblr partly as a notebook for things I plan to repurpose elsewhere. I also enjoy its “ask” function, which allows readers to communicate with me directly, mostly with relevant questions, constructive criticism, or (best of all) praise for my work, the occasional quasi-threat to my genitalia notwithstanding. With yesterday’s apparent collapse of Twitter—you pretty much have to pay to use it now?—I wonder if the long-threatened repatriation of Tumblr natives from Twitter back to their homeland will finally happen.

What attracts me to these two? Just after Harold Bloom—and each of them in her own way more lucidly than him—they were my earliest models of, well, not so much the intellectual life per se, as the life consecrated to the arts and humanities. I found Sexual Personae and Against Interpretation in used bookstores when I was 17 and that was that. Continuing this post’s apparent motif of adolescent nostalgia now that I’m back in the suburbs for a week, I distinctly remember having to write a semester report on my work for my high-school art class and quoting Sontag to justify my not in fact having completed the work on the grounds of conceptualism or whatever. Insufferable! And my art teacher duly wrote in the margin, “This sounds like a lot of bullshit to me…”

I am aware that Anna Khachiyan has now referred to this book several times, but, just as one listened to the band before it got popular, I myself read it in 2004, plucked from the new books shelf at the Carnegie Library. I never became much of a Kael reader, though, possibly because I don’t love movies enough—I love them less than Kael, Paglia, or Sontag did/do. We might fancifully read Renata Adler’s celebrated demolition job on Kael as a ghostly double of the polemic against Paglia that Sontag never wrote: “The degree of physical sadism in Ms. Kael’s work is, so far as I know, unique in expository prose.” Adler, as I recall, once commended “the radical intelligence in the moderate position,” a good description of where Sontag and Paglia ended up, each in her own distinct way.

The impassioned and excessively personal sequel to this Tumblr post must go unreproduced here; I will probably even have to delete it eventually, but I can give you a link for now. The short version, for when the post disappears, is this: I announced that I am about to write a play, and I announced further that it will be called Saturn Dreaming of Mars.

I won’t add too much to what I said in response to that Sontag/Paglia post originally, beside that I also admire Sontag’s tormented moralism-aestheticism, her quest to figure out how to do something like a European humanism without the first principles so much of that stuff derived from is admirable (if open to the critique you lodge that maybe in the end just *being* a good person is more vital than thinking about what that means.) I’ve been delinquent in keeping up with MA, maybe I’ll catch up this week.

Good piece.