A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

First a scheduling note for paid subscribers. I’ve doubled up on posts this weekend—today’s Weekly Readings + my annual Shakespeare’s birthday piece, this time an essay on The Winter’s Tale—and will do so next weekend—with a Weekly Readings and an April Books round-up, the latter with reflections on Bolaño, Jünger, Moshfegh, the Books of Samuel and Kings, and others. To avoid crowding your inboxes, I have decided that chapters of my serialized novel Major Arcana will appear on Wednesdays instead of Mondays starting this week and from then on.

This Wednesday in Major Arcana, we will continue the saga of Jessica Morrow, my emblematic Millennial in a narrative otherwise consecrated to the psychological, social, and indeed metaphysical travails of Gens X and Z. Of last week’s episode, “Out of Time,” a reader comments on Tumblr,

Wonderful chapter, by the way! A masterful execution of the serialized technique—effortless in its transition from contemplative melancholy to prurient intrigue all within 2,000 words!

If you haven’t yet upgraded to a paid subscription, you’re missing this “masterful execution” in both text and audio formats. Next week I will be announcing future amenities for paid subscribers, probably involving a series of interactive courses or lectures on great works I am often requested to comment on. Weekly Readings, however, will always be free. This week’s is inspired by my recent discovery of English writer Colin Wilson.

High Flyer: Bibliomancy, Metaphysics, and the Theory of the Novel

This week I used Substack’s microblogging Notes feature to share my latest experience in literary synchronicity or divination-by-book.

First, a few words about this unsystematic practice. I almost never follow any sort of reading list or reading plan. I take recommendations that speak to me, I constantly wander in libraries and used bookstores, I am led by the controversy of the moment, I stop at every Little Free Library I see, and I follow esoteric links in blog and social-media posts. I have never “researched” anything.1 Often, in my long life as a writer and a teacher, I have somewhat researched a topic after I have written about it or lectured on it. I trust that what we call intuition is simply knowledge pulsing into the present from the future rather than from the past—time, to the alert eye, being an illusory effect of living in three dimensions.

You may be scandalized, but this is established literary science, the only science I trust, explored not only in the paradoxes of retrospective influence noted by Borges and Bloom—paradoxes that for one exegete can only be explained with reference to the cinema of time travel—but also in that beautiful climactic passage from A. S. Byatt’s superb and now perhaps under-discussed Possession quoted as the ideal of reading and writing by Toni Morrison in Playing in the Dark:

Antonia S. Byatt in Possession has described certain kinds of reading that seem to me inextricable from certain experiences of writing, “when the knowledge that we shall know the writing differently or better or satisfactorily runs ahead of any capacity to say what we know, or how. In these readings, a sense that the text has appeared to be wholly new, never before seen, is followed immediately by the sense that it was always there, that we, the readers, knew it was always there, and have always known it was as it was, though we have now for the first time recognised, become fully cognisant of, our knowledge.”

I suggest that we can attain this recognition of the always-already known precognitively, in advance of actually passing our eyes over any particular words; the words circulate, as it were, through the air. The advantage of this practice: I allow sometimes revelatory chance to dictate what I actually do read since I spend most of my time assuming I have already read what I plan to read but may not quite have read yet.

Case in point: in a Subtack post advertising two unpaywalled pieces from the latest Mars Review of Books—Tess Crain reviewing new novels by men, Alex Perez reviewing new novels by women, both excellent—editor Noah Kumin wrote the following on sex, gender, and the novel:

What’s going on here? Questions of sex and gender have always been germane to the novel. Just read about the novel’s history, especially the history of the first bestseller, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela.

As I Noted, in this quotation the words “novel’s” and “history” are both linked: “novel’s” to Ian Watt’s Rise of the Novel, expectedly enough, but “history” not to a similarly predictable academic tome of the sort those of us who got what Kumin calls “infested with theory” in graduate school might expect (Nancy Armstrong’s famous Foucauldian spin on Watt, Desire and Domestic Fiction, for example) or even something in a superficially similar vein but a good deal more psychedelic (e.g., Margaret Anne Doody’s magisterially goddess-feminist True Story of the Novel).2

The link goes rather to a brilliant book I didn’t know existed before Thursday but a pdf of which I have now happily read in its entirety: Colin Wilson’s The Craft of the Novel. I very dimly knew who Wilson was before clicking this link: a precocious English author of the midcentury Existentialist study, The Outsider, who became some kind of mystic or occultist in his latter days. In the mental archive, I had him shelved under “to read for historical purposes someday; not urgent.”

Kumin is a forward-thinking man, however—see his recent piece, “Why I Am Not a Luddite,” whose definition of Romanticism and whose advocacy of Girard I probably disagree with, but which I nevertheless take seriously—and I hadn’t in any case known that the erstwhile boy-outsider and later occultist had written a handbook on creative writing. I found The Craft of the Novel on Internet Archive—get it while it lasts—and figured I’d read a page or two out of curiosity.

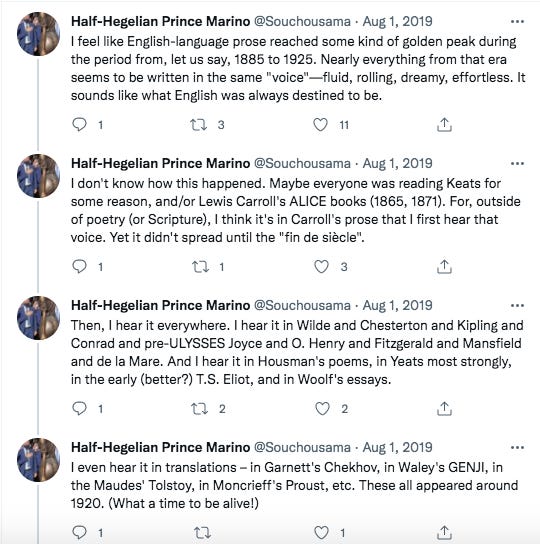

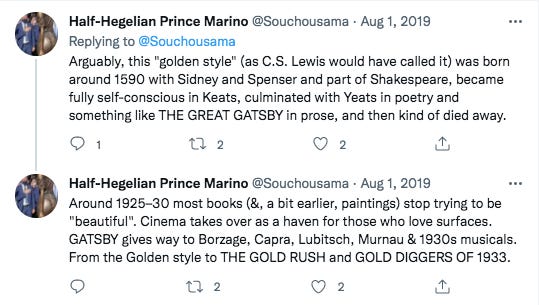

As it happens, however, Wilson writes in that irresistible style of poetically plain English perfected by British writers sometime between the 1880s and the 1960s, between the Victorian and the the postmodern maximalisms (Dickens, Rushdie) that were the opposites of its addictive clarity. While Orwell is the American’s main example of this style, I wasn’t surprised to learn from The Craft of the Novel’s opening pages that Wilson considered himself a disciple of George Bernard Shaw. (The author of over 100 books, Wilson unsurprisingly published a treatise on Shaw.)3 Before I knew it, I’d read half the book. Despite its title, it has nothing to do with craft. Wilson, championing books he himself describes as clumsily written throughout, says explicitly, “when a novelist knows what he wants to say, the technique will take care of itself.”

For our author, the novel is an unprecedented step forward in human consciousness. It begins not with Greek or medieval romance, nor with the comparatively crude adventure stories of Cervantes and Defoe, but really gets started with Richardson’s Pamela of 1740: a waking reverie over everyday life available to the hoi polloi and thus popularizing for the first time in human history the creative ability of the mind to roam and wander in quest of its highest truth.4

Once we understand that this mental expansion is the novel’s purpose—that the novel is, in language Wilson borrows from his beloved Shaw, a magic mirror in which we behold our own souls—we will understand that novels ought to be thought experiments, not the mere testimony of the ego (as it becomes in Romantic and modernist novels from Goethe to Joyce) or the mere notation of exteriors (as it becomes in the realists and naturalists like Flaubert and Hemingway).

The novel declines into Romantic egoism and naturalist nihilism, neglecting philosophic wisdom, almost as soon as it comes to birth in Wilson’s baleful historical narrative. Joyce serves as his arch-nemesis: everybody knows that Joyce fuses Romanticism and realism in Ulysses, but for Wilson this has the effect of synthesizing into a monumental dead end, an almost unsurpassable wall at the terminus of the novel’s history, the lie of egoism (Dedalus’s non serviam) and the meaninglessness of naturalism (Bloom’s flânerie). Young Werther and Madame Bovary collapse of exhaustion into one another’s self-centered arms at the finale of literature.5

Wilson sees the best hope for the novel’s revival in the 20th-century emergence of science fiction and fantasy. Here, in Lovecraft and Tolkien and David Lindsay, we find fiction as true thought experiment, the novel as a shuttle in which we may sail the uncreated void of inner space.6

I could disagree with elements of Wilson’s argument on every single page, from his sometimes briskly dismissive evaluation of individual writers (surely there is more to Emily Brontë, to Faulkner, to Nabokov than he acknowledges) to his advocacy for the germinal texts of the nerd culture that would overtake the 21st century without the promised mind-expanding effects. He also makes no allowance for readerly pleasure in language and form per se, especially after the hegemony of poetry. Is the near-worshipful stance readers take today toward Cormac McCarthy and Toni Morrison, for example, unrelated to their commitment to prose euphony in a period when the major American poets were John Ashbery and Louise Glück, authors who, whatever their other merits, would not as a matter of principle provide us with verbal splendor?

Nevertheless, the Shavian psychedelia of the argument—by “Shavian psychedelia” I mean to suggest an Anglo-Protestant version of Platonic ecstasy, also present in Blake and Yeats and Woolf, to which the more this-worldly Catholic ecstasies of a Flaubert or a Joyce will necessarily appear hostile, decadent—appeals to me with its fierce insistence that the novel must mean something. Take this paragraph:

Once again, we are back with David Lindsay’s distinction between novels that describe the world and novels that try to explain it. Or, more simply, between ‘high flyers’ and ‘low flyers’. Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë and Anthony Trollope are fine novelists; but they are low flyers. Rolland, Sartre, D. H. Lawrence, Dostoevsky, and Lindsay himself, were high flyers. It is much easier to write a successful ‘low-flying’ novel than a successful ‘high-flying’ novel.

Again, I have problems with the examples—reread Mansfield Park, reread Villette, both of them religious testaments, flying as high as you like—but then I have never even read Romain Rolland, whom the infinitely well-informed Wilson seems to treasure.

Even better, Wilson proposes a literary hierarchy that can be arranged as a graph: at the low end are novels that reflect “the Communal Life-World,” the bestseller realm of common opinion we all share; in the middle are novels expressing an “Individual Life-World,” like those of Austen or Dickens or Balzac, particularized idiosyncratic achievements of distinct sensibilities; toward the high end are novels surpassing both the cliché-land of the Communal Life-World and the egoist prison of the Individual Life-World to attain “Purely Objective Vision,” the disclosure of the cosmic vastness above and beyond the Communal and Individual Life-Worlds though equally open to all: here we find Goethe, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Shaw, and very few others—so few others, Wilson says, that the post-Joyce novel is not only not dead but has barely even begun to live.

As I continue to write my own novel on art and magic—a (magical) realist novel of the kind to which Wilson would prefer fantasy or science fiction, except that nowadays our society is so fragmented that realism can only be written as science fiction, the exposition of the alien worlds into which the Communal Life-World has digitally disintegrated—I find Wilson’s idealism more fortifying than any mere treatise on “craft” could ever be. Upholding Shaw and censuring Eliot and Joyce, Wilson concludes:

It is possible that the novel may never again play such an important part in human development as it played two centuries ago. Yet there is no reason why it should’t. All that is necessary is that the novelist should recognise his true purpose: not merely to reflect the ‘immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history’, but to liberate the human imagination and to give man a glimpse of what he could become. He must learn to understand what Shaw meant when he said that a work of art is a magic mirror in which man is able to see his own soul. And when he has grasped that, he will discover that his magic mirror has an even more useful function: to reveal the future direction of human evolution.

Synchronicity is not happenstance, however, and divination is not accident. A pattern is required to prove that the universe intends a message. Accordingly, I went to the used bookstore on Friday night, after reading The Craft of the Novel on Thursday night and Friday afternoon, and what did I find but Wilson’s Outsider and his History of the Occult, neither of them expensive? I am 110,000 words into a novel about the occult but have never read a history of the subject. (I told you I’ve never researched anything.) Here one is, complete with an account of “Faculty X,” the faculty which I assume explains how I know things before I know them. As the sages say, things are always working out for me.

My dissertation is an original commentary on well-known texts, literary and theoretical, rather than a report on any kind of archival digging. I remember pugnaciously warning my committee in the prospectus, “This will be a work of literary criticism, not literary scholarship.” (I must have been an immense pain in the ass.)

Doody’s treatise—arguing for a continuity from Hellenistic Romance to contemporary world fiction, with the novel as a metropolitan, multicultural, and divine-feminine perennial force under the patronage of “the Goddess”—is enormous, almost Clarissa-length; I must read the whole thing someday, but I’ve sampled enough to know its metaphysical feminism usefully transgresses what I’ve elsewhere described as the feminism-as-misogyny enshrining power and technocracy we find hegemonic today.

As for Armstrong, I will have to write you an essay about her eventually. She was my advisor’s advisor, my institutional grandmother: a hard-headed exponent of radical anti-humanism at odds with such sentimentality as Doody’s (Doody began her academic life as a Richardson scholar). Whether Armstrong should be described as radically left-wing or radically right-wing I could never quite decide, though she herself would obviously insist on the former. To see what I mean, consider the part of Armstrong’s Desire and Domestic Fiction about Mr. B’s attempted rape of Pamela. This is a purely textual trespass, Armstrong claims. The bourgeoisie effectively invented the modern concept of rape in order to create the illusion of an inviolate proprietary inner self (i.e., the individual) behind the externally political contest for power actually determining our existence, or so Armstrong argues:

Thus Richardson stages a scene of rape that transforms an erotic and permeable body into a self-enclosed body of words. Mr. B’s repeated failures suggest that Pamela cannot be raped because she is nothing but words. As such, she demonstrates the productive power of the trope of the contract. Presuming to rescue the pure and original Pamela, Richardson creates a distinction between the Pamela Mr. B desires and the female who exists prior to becoming this object of desire and who can therefore claim the right of first property to herself.

No wonder in her sequel, How Novels Think, Armstrong ends by celebrating Mrs. B’s literary descendant Count Dracula as a model for human subjectivity after the family, the family along with individualism being the perennial adversaries of her polemically anti-humane criticism:

As I have tried to show by pointing out the utopian potential in Dracula, the trick of formulating a more adequate notion of the human is to find a way of articulating what we lack in positive rather than negative terms: as the sameness we acquire by virtue of always and necessarily falling short of the cultural norms incorporated in the modern individual and reproduced by the nuclear family.

I take this opportunity to share a Twitter thread on English prose style from Marino I screenshotted almost five years ago:

Also, despite my prevailing literary tastes, allegiant to his opposite number in the crypto-Catholic aesthete Wilde, I do love Shaw. I wrote a long essay about him last year.

I hated Pamela, for whatever it’s worth. I’ve never read Richardson’s mammoth follow-up, Clarissa, despite the high praise as the greatest English novel it’s received in some quarters. Once, in a graduate seminar, I sat next to a budding 18th-centuryist reading Richardson’s opus. I asked her, “How’s Clarissa?” Before she could reply, the colleague sitting on the other side of me whipped her head around and demanded, “My God! Did you just ask about her clitoris?” The Clarissa reader glumly replied, “Believe me, I’d rather talk about that.”

That I think Wilson has misread Ulysses should go without saying. He grasps that the novel was meant to be affirmative in the end, but, too concerned with Dedalus’s outsider-egoism, he misses Joyce’s censure of his younger self via the moral worth attaching to the sympathy and worldliness of Bloom. This, as much as any comparable ethical assertion in Tolstoy or Dostoevsky, gives the sometimes desultory and parody-ridden narrative its spiritual impetus. For my own critique of Ulysses, despite my reverence for Joyce’s achievement, see here.

Wilson argues that “purely as a novel, The Lord of the Rings must be regarded as one of the most successful works of art of the twentieth century.” Loathing the movies, I’ve never read the books. I did once argue that Joyce was far more important to the 20th century, if less read within it, than Tolkien—that we are living in Joyce’s world, not Tolkien’s, because Tolkien may have addressed the cultural infantry, as it were, but Joyce addressed only the generals. Wilson also reserves high praise for David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus, which he startlingly calls “the greatest imaginative work of the twentieth century—possibly in all literature.” Two people who might agree with him are Harold Bloom, whose own only novel is apparently an imitation of Lindsay’s, and Alan Moore, who’s praised Lindsay in similar terms. Despite this, I have yet to take the eponymous voyage. Speaking of Alan Moore, I suspect Wilson influenced at least his early work, up to From Hell (Wilson was a Ripperologist, and in fact coined the term). Reading about Wilson, I find he was interested in planarian worms. Anyone familiar with Moore’s classic run on Swamp Thing (not Marsh Man, I emphasize for Major Arcana readers) will recognize these intrepid invertebrates.

The two of us are going to start a Colin Wilson revival right here, I can feel it (through occult precognitive abilities).

Regarding the amorphousness between far left and far right, I’ve always thought that ex lefties make the best conservatives, not just because you actually have to have a certain amount of intellectual vigor on the far left, but because the real enemy of the American academic left has always been the middle classes and the left-liberal part of the middle class is exactly whom the majority of conservative rage (absent any notable racial or gendered controversy in any given moment) is directed towards. Wilson I’ve never read, maybe I’ll have to. I’m always a bit skeptical of the line (Leavis thought this too iirc) that only a narrow vein (of course no longer in production) of fiction constitutes the true novel. Agree with you about sci-fi and avant garde elements being necessary to represent reality now, but we’ve talked about that before.