A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

My critical sabbatical continues as I write my novel, Major Arcana, soon to be serialized for a small fee on Substack. (You might please pledge a subscription today.) I have attained the novel-length word count of 50,000+ words, thus surpassing a serious psychological barrier in the completion of any novel. I have also discovered the structure and plot, at least broadly. Only composition remains, though in the composition I will discover many secrets I don’t yet know—things I don’t even know are secret yet. (A novel is not a map; it is the actual path you carve through the unexplored territory.) I hope to serialize by spring.

In the meantime, continuing this year’s theme so far, another brief essay on the more mystic aspects of literature. Today, we will consider whether or not great writers are capable of prophecy in the most crude and literal sense: the foretelling of the future.

Supratemporal: Literature as Divination

Of the Silent Generation giants now passing from the stage, Don DeLillo is the prophet. Philip Roth was the enfant terrible turned éminence grise, Joyce Carol Oates the indefatigable visionary, Joan Didion the model of style, Cormac McCarthy the tradition’s last torchbearer, Thomas Pynchon the technician and encyclopedist, Susan Sontag and Cynthia Ozick and Toni Morrison in their different ways and for their different constituencies the moral conscience; but only DeLillo had the power to tell us the future.1

In the minor 1977 novel, Players, about a yuppie turned terrorist, one of the protagonists reflects of the recently built World Trade Center, where she works as a grief counselor,

To Pammy the towers didn’t seem permanent. They remained concepts, no less transient for all their bulk than some routine distortion of light.

In the minor 1991 novel, Mao II, a refraction of the Rushdie affair’s early days, the novelist hero muses,

“What terrorists gain, novelists lose. The degree to which they influence mass consciousness is the extent of our decline as shapers of sensibility and thought. The danger they represent equals our own failure to be dangerous. […] Beckett is the last major writer to shape the way we think and see. After him, the major work involves midair explosions and crumbled buildings. This is the new tragic narrative.”

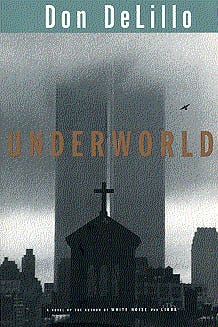

The most major of DeLillo’s major novels, Underworld (1997), would be published with a book jacket showing the Twin Towers photographed through a dark filter, shrouded in a smoky cloud, with a bird in flight seemingly about to collide with the wall of glass. In the foreground stands a church steeple like a funerary monument.

After 9/11, an interviewer told DeLillo that his name kept coming up, as if he’d foreseen the attacks, and, like a prophet burdened with his terrible knowledge, he replied—I quote from memory; I can’t find whatever website I read this on in 2002—“I wish it wouldn’t.”

We can debate how much DeLillo’s most famous and most funny major novel, White Noise (1985), should be credited for prescience. Its farcical apocalypse of a chemical spill that becomes an “Airborne Toxic Event” in a Rust Belt college town followed both Three Mile Island and the Bhopal disaster, though it preceded Chernobyl—and, for that matter, Bhopal happened the month before the novel’s publication, which means that DeLillo had finished the book just before a similar disaster unfolded in real life. The last time I taught the novel to an in-person class, it was the week before spring break 2020, from which we would not return to the classroom; I likened the Gladney family’s anxious dinner-table chatter as the Toxic Event neared to our own blitheness—this was the last week of blitheness—in the face of the impending pandemic.

As I write, a toxic cloud from a train derailment threatens East Palestine, Ohio, not far from my hometown of Pittsburgh. Ironically—or prophetically—Noah Baumbach filmed his recent adaptation of White Noise (see my review here) in the area; residents who later had to evacuate acted as extras in the film’s evacuation sequence, which in both film and novel turns on the postmodern irony that officials treat the real disaster as a model and test-run for future simulated disasters. The extra/evacuee CNN chose to interview for the story bears the surname Ratner, like the protagonist of one of the only DeLillo novels I haven’t read, Ratner’s Star (1976).2

How did DeLillo accomplish such sortilege? Must we stone this Catholic schoolboy for a witch, as commanded early in the Bible? On the other hand, if DeLillo’s Abruzzese Catholic forebears were anything like my own, spells and fortunes formed part of the faith, not a betrayal of it. Old-world religion aside, the answer may have something to do with technology. Pay close enough attention to the white noise of media, whether mass- or social-, unscramble and rescramble the signal for yourself, as in Burroughs’s cut-up method, and you will begin to receive information from the future as well as the past—presuming time, from a fifth-dimensional perspective, to be an accomplished structure in fourth-dimensional space. Great writers, then, have access to the fifth dimension. I count this as the materialist explanation.

Earlier writers, on the other hand, without access to modern media or modern physics, saw writers themselves as mediums, channels for spiritual messengers. Consider the Neoplatonism of both Shelley’s “A Defence of Poetry”—

Poets, according to the circumstances of the age and nation in which they appeared, were called, in the earlier epochs of the world, legislators, or prophets: a poet essentially comprises and unites both these characters. For he not only beholds intensely the present as it is, and discovers those laws according to which present things ought to be ordered, but he beholds the future in the present, and his thoughts are the germs of the flower and the fruit of latest time. Not that I assert poets to be prophets in the gross sense of the word, or that they can foretell the form as surely as they foreknow the spirit of events: such is the pretence of superstition, which would make poetry an attribute of prophecy, rather than prophecy an attribute of poetry. A poet participates in the eternal, the infinite, and the one; as far as relates to his conceptions, time and place and number are not.

—and Emerson’s “The Poet”—

For poetry was all written before time was, and whenever we are so finely organized that we can penetrate into that region where the air is music, we hear those primal warblings, and attempt to write them down, but we lose ever and anon a word, or a verse, and substitute something of our own, and thus miswrite the poem. The men of more delicate ear write down these cadences more faithfully, and these transcripts, though imperfect, become the songs of the nations. For nature is as truly beautiful as it is good, or as it is reasonable, and must as much appear, as it must be done, or be known. Words and deeds are quite indifferent modes of the divine energy

Shelley disclaims mere poetic fortune-telling as “superstition,” but then goes on to credit poets for a vision outside time; Emerson more simply pictures the poet paying a visit to the Platonic forms, though he, too, sees poetic vision as supratemporal, equally observant of what in the third dimension looks like the future as of what in the third dimension looks like the past, though for the 5D poet past and future are simply “over here” and “over there,” both equally perceptible. Shelley and Emerson, I’m sure, had Dante in mind, the pilgrim able to tell souls in the afterworld what had become of their names, the poet confident in prophesying the future of polity and papacy.

Justly controversial writer and Twitter personality Logo Daedalus cites Blake, who saw angels and conversed with spirits, just like his British descendants in the composition of illuminated epics, Alan Moore and Grant Morrison, also cited in recent posts.

My own modest share in literary prophecy is still unfolding. The Quarantine of St. Sebastian House, my pandemic novel, written between mid-March and mid-April 2020, begins with a sense of the virus’s apocalyptic threat and ends in the clear conviction that the authorities’ totalitarian response to the virus was the true calamity all along—a conviction events subsequent to April 2020 would bear out.

In Portraits and Ashes, mostly written in 2013, I imagined a collectivist cultus of desperate youth seeking to escape the prison of the flesh. Along with gender-redacting surgeries, they adopt the personal pronoun “it.” Gender-nullification surgery and the “it” pronoun both now feature on the social landscape, as they did not in 2013: for example, the aforementioned Grant Morrison has listed “it” among acceptable pronouns for him-their-itself alongside “he” and “they.”

To whatever extent I may be congratulated for prescience, I didn’t accomplish it through any calculated extrapolation. My fiction more or less comes to me as I write. When it doesn’t come, I don’t write. Writing of this sort is not, as the MFA schools construe, a craft, like constructing a chair. A poem, a novel, is not a chair but the tree you chop down to make the chair. Shelley again:

Poetry is not like reasoning, a power to be exerted according to the determination of the will. A man cannot say, “I will compose poetry.” The greatest poet even cannot say it; for the mind in creation is as a fading coal, which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness; this power arises from within, like the color of a flower which fades and changes as it is developed, and the conscious portions of our natures are unprophetic either of its approach or its departure.

As I write, North America appears to be under attack by either ETs or the CCP, though the latter also claims to be afflicted with a UFO. Coincidentally, I am watching the Chinese TV adaptation of The Three-Body Problem, which I’ve never read. I just finished the 11th episode, 10 minutes shorter than the others. If the YouTube comments are to be believed, the government demanded that a sequence showing the torture of a dissident intellectual during the Cultural Revolution be cut. The episode nevertheless makes clear its censure of Mao’s communism for being brutally void of any ecological consciousness (the series’s several casual mentions of “sparrows” I take to be similarly pointed); meanwhile, I thought the episode’s scenery-chewing villainous commissar wasn’t wholly wrong to decry environmentalist doomsaying and misanthropy. The series upholds scientists, not artists, as its heroes; its applied-physicist protagonist is cursed with a kind of literal foresight, fourth-dimensional perception being the sign of a threat from beyond. “Physics does not exist” is the suicide-inducing threat that bears down on the series’s scientists. Is this, the ability to subsist in a universe whose laws we cannot use reason alone to formalize, the difference between science and art? Time will tell.

Speaking of Susan Sontag and prophecy: you won’t and don’t have to believe this, but in about 2018—around the time I delivered this lecture—I was writing down vague ideas for a utopian poem or a science fiction story or something, and I wrote a line about an imaginary film director in the future that read,

He won plaudits in 2045 for bringing Kristen Stewart out of a long and secluded retirement to win her first Academy Award for a star turn as Susan Sontag in the harrowing Sarajevo.

But will there still be Academy Awards in 2045? Will there still be actors and not AI simulacra? Here, prophecy fails me.

So insightful on too many levels to count here. So I'll choose one, John: The process of creating as a writer. I too am at 50,000 words on a novel I'm trying close to finishing, and I too see the process—even as I get the structure straightened out and have a better sense of what I'm doing—see the process as one of discovery. Excellent piece. Love reading you.