A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Recent controversies over masculinity, ethnicity, and class in the literary world sent me back to Junot Díaz this week. He was a writer I resisted and resented during the period of his hegemony. I was even relieved at his cancellation. But then I remembered J. M. Coetzee’s argument in his essay “What Is a Classic?”: any work that hopes to survive has to be in some measure cancelled first. No arrangement of vision in language will last if it can’t withstand the fading away of the social, political, and cultural atmosphere that first gave rise to it. Hence the “John Dizikes rule” invoked in my piece: read no novel less than a decade old. 15 years later, does Díaz’s celebrated first novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, still stand, long after its early-Obama celebration of “nerdiversity” has come to seem naive? Almost. Not quite. But maybe if he writes something better, it will be fondly remembered as the prologue to a grander achievement. In any case, I had fun writing the review. As Wao’s namesake Wilde claimed, criticism is the only civilized form of autobiography, so I stashed various fragments of my own life inside the essay, essentially to say, in riposte to Díaz’s aesthetic, that my grandmother was magical and I did love Superman, but neither of those facts absolved me from what I quoted Ann Manov in the very first of these newsletters as calling “the responsibilities historically incumbent upon the civilised mind.”

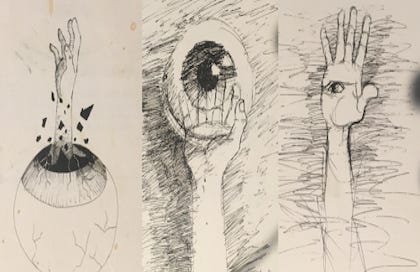

For my Wednesday creative-writing post, I was still clearing out that paid Medium account where I’d previously published a lot of my stories to preserve them against the vicissitudes of small literary journals, which are always locking everything up in print and then going out of business or going out of business and taking their web archives with them. Accordingly, I shared my 2014 story, “The Embrace,” which originally appeared in print in the first issue of Winter Tangerine. It’s my own admittedly rather strange take on masculinity and femininity, with an almost-realist (though, as I prefer, oneiric) approach to subject matter Díaz’s nerd cohort would label “Lovecraftian.” In short, it’s about a girl and an octopus (“but what was its name for itself?”).

Below I offer a capacious and meandering essay (with appearances from Naomi Kanakia, Bronze Age Pervert, Joseph Conrad, Edward Said, Dominique Eddé, Tara Isabella Burton, and Fyodor Dostoevsky) on what I call literary vision.

Constructive Criticism: The Writer’s Vision and the Whole of Reality

Naomi Kanakia has written a popular essay at the LA Review of Books on “The Dreariness of Book Club Discussions”—except that most of the essay could apply equally to discussions of literature in the college classroom. The options Kanakia surveys and dismisses—New Critical formalism, deconstructive symptomatic reading, Marxist-Foucauldian power analysis, and the book reviewer’s expression of taste—are the very ones I used to be tasked with inculcating in students when, as an adjunct professor, I taught the intro-the-English-major course, Textual Analysis. In the face of these alternatives, Kanakia arrives at a solution and synthesis close to my own:

Seen in this way, by paying attention to what the author doesn’t say (deconstruction), or why the author said it (power analysis), or how the author said it (New Criticism), or how we felt about what the author said (book reviewing), we’re missing the point, which is that something happened. Something was at stake in this story. Characters made decisions. Those decisions had consequences. And it’s in that specificity — in what Hegel would call its “determinate content” — that the real value of the story lies. I personally don’t think it makes sense to spend half an hour talking about the language and the structure of The Sound and the Fury and only five minutes talking about how they castrated Benjy. The castration is at the core of the story, and all of the rhetorical and aesthetic devices are meant to amplify that story, not cover up or erode it.

While I think formal analysis (“how the author said it”) deserves more priority than Kanakia grants it, especially since everybody fancies themselves writers these days; while I shy from the word “moral,” which suggests to me local and often just parochial standards of good behavior; and while I hesitate at a Hegelian prioritization of content over form given the role this kind of thinking played in Soviet aesthetics, I still agree with this passage in general.

I try always to arrive at what I call a work’s overall vision: the entire sense of life it communicates, both through its “determinate content” (the characters, the plot) and its style and form. In the best fiction, form and content strive together for that never-to-be-realized unity whose inevitable failure does make deconstructive criticism always relevant as a caution against hubris, though never granted the final word. The literary aspiration toward holistic vision, whether the reader’s or the writer’s, demands a constructive rather than a deconstructive attitude.

A strange confluence of texts brought all of the above into focus for me this weekend. First, I saw on Twitter that the vitalist luminary of the dissident right, the pseudonymous Bronze Age Pervert, claimed Joseph Conrad as his favorite novelist.

A few observations about this Tweet. First, I’m not aware that Foucault ever said anything about Conrad. Second, Edward Said loved Conrad and—himself a bit of a displaced aristocrat, an exiled cosmopolite with small-nation sympathies—even identified with him.1 Conrad’s politics were reactionary, but reactionary liberal. His anguished letter to Irish anti-imperial activist Roger Casement in the back of the Norton Critical Edition of Heart of Darkness—to the effect that “Europe” should intervene to restrain the Belgians in the Congo—sounds like Susan Sontag under fire in Sarajevo.

Applying a bit of deconstructive queer theory, I suspect BAP’s vitalist homoerotics are the unspoken factor in his fervor for Conrad: all those male mariners in close quarters and frequent peril, “facing it, always facing it” together. Many years ago, in graduate school, assembling my reading list for the comprehensive exam, I added Lord Jim, mainly because I’d never read it, whereas I’d read Heart of Darkness four times by then.2 My advisor overruled my choice and insisted that Heart of Darkness was indeed more relevant to my project on modernist sentimentality. “Unless,” she said, narrowing her eyes at me, “you’re interested in the sentiment of homoeroticism.” I discovered later that she’d written what Kanakia would call a “power-analysis” essay on E. M. Forster that turns on his gay-male-misogynist elevation of Lord Jim over Charlotte Brontë’s Villette, since the latter is preoccupied in putatively feminine fashion with heterosexual love and romance, while the former concerns men wedding themselves to high ideals (which is not, by the way, true: Villette, among other things, is a religious novel).3

Speaking of amours, Edward Said’s mistress, the Franco-Lebanese writer Dominique Eddé, wrote a beautiful memoir of their romance that doubles as an intellectual, political, and aesthetic assessment of the critic. She finds his preference for Conrad over Dostoevsky something close to a character flaw, one that echoed what she judges to be his political credulity in the face of totalitarian politics (Marxist and Islamist) symbolized by his similar dismissal of Camus:

Said is more threatened by Dostoevsky’s world than by Conrad’s. Dostoevsky destabilises and disarms him, whereas Conrad provides him with a clock and a context in which to reconcile anxiety and ethics, his two preoccupations. Anxiety absorbs guilt, ethics offers him a way out which, though insufficient, has the great merit of calming anxiety by offering a morality founded on will, character and action—the morality of ‘doing what you have to do.’ In other words, steering the ship to port, against all diabolical temptations and notably money and women. There is nothing of this in Dostoevsky, for whom external and internal storms are intertwined, will has little power against instinct, reason is infiltrated by madness and the shadow of God is everywhere, including within characters who are unbelievers. Here lies the gulf between the worlds of these two novelists. God and madness haunt Dostoevsky’s world but are absent from that of Conrad who, although he too exists in an atmosphere of torment, nerves and guilt, invents a form of order founded on morality, whereas Dostoevsky follows chaos through the soul’s every fold and wrinkle.

So with all this in mind, I was interested to see Tara Isabella Burton using Dostoevsky to rebuke what else but the “black-pilled” BAP worldview, just as Eddé used Dostoevsky to reprove Said’s un-visionary preference for the black-pilled (in fact Schopenhauer-inspired) Conrad:

It is this logic that we find throughout so much of the reactionary right: a valorization of the “natural,” of “strength,” of difficult truths and those who are willing to accept them. It is a valorization of authoritarianism—by state, by church, by strong and rugged men, by “dark elves” (this last one courtesy of blogger Curtis Yarvin, whose fanatically hierarchical reactionary worldview extends to the belief that some races are better suited for slavery than others) who are willing to make the tough calls that ordinary people are too afraid to face. It is a mood, too, that we find—albeit with somewhat less frequency—in certain apocalyptic memes on the online left: the idea that “all this” is little more than a “trash fire,” that “because capitalism,” our lives and our obligations do not matter. It is the end of history, after all (or so this story goes), and so hedonism can double as self-care.

What the black-pilled online reactionary and the left-academic “power analyst” might be said to share is a certain materialist reductivism belonging to (and perhaps best left in) the 19th century, whether Darwinian biologism, Marxian economism, or Schopenhauerean-Nietzschean vitalism. None leaves enough room for the chaos of the soul, though this needn’t be defined exclusively in Dostoevsky’s or Burton’s Christian sense. (Try the expansive Emerson, for example, who was Nietzsche before Nietzsche, but much more besides; for him, nature and spirit were one.)

Dostoevsky is the greater novelist than Conrad, then, because his vision is more comprehensive, more inclusive of the heights and depths of the real. When we arrive at an assessment of authorial vision—something larger than mere style or mere content but synthesizing both—then and only then may we judge.

In time-honored racist fashion, our ultra-right-wing Pervert has his “Third World” writers mixed up. He means Chinua Achebe, who wrote the canonical critique of Conrad as a “bloody racist.” That intensely moralizing and polemically simplified essay is the 20th-century forerunner of 21st-century online social-justice criticism, not Said’s suave and sophisticated prose, which Camille Paglia compared to Walter Pater’s in Marius the Epicurean.

I’ve since read all of major Conrad, though I still have the minor novels to go. I wrote about his short novels—sans Heart of Darkness—here. The paragraphs of interest for a political critique are these, which follow a quote from a critic who cited both Conrad and Said as partisans of “lost causes” as such, in which category the critic somewhat scandalously included the Confederacy alongside a company of struggling or defeated Third World Liberation movements:

And if we bristle at finding the Confederacy grouped with the Vietnamese and the Palestinians, we might recall that Karl Marx praised Abraham Lincoln and the British in India for the same reason: from his point of view, both broke the settled order of regressively hierarchical societies, whether in the American South or the Global South. True, these northerly forces introduced new forms of hierarchy, but modern, rational, and centralized ones communism would be able easily to appropriate for the people. (This is why honest Marxists today, if any remain, celebrate corporate monopolization.)

In contrast to Marx and his ferociously progressivist descendants of all parties, Conrad speaks on behalf of those left behind, for good reasons and bad, in a world that prefers machines to men; he speaks for those battered by the storms and abandoned in the calms of an incomprehensible oceanic cosmos whose only possible justification or redemption is its weathering under the hand of an assiduous, if only human, artificer.

I find both ahead-of-their-time inventive novels, 19th-century modernism, and see no reason to choose between them, though I might personally prefer Villette, if only because, gender aside, the subject matter is closer to my own experience than maritime adventure. (I wrote about it here.) Lord Jim is as if Faulkner had written Treasure Island, Villette as if Beckett had written Mansfield Park.

"The literary aspiration toward holistic vision" is a doomed mission for novelists, which I suppose makes it beautiful in its tragedy. That's a term I'll steal happily, thanks for it!

In what you've read of current criticism, who are the critics who best balance style and substance to reflect on novels' vision of life in their reviews?

Love the defense of Said here. I remember watching a discussion between, I think, Cornel West and Judith Butler in remembrance of Said. West spent a lot of time asking how a radical like Said could have liked a Tory like Jonathan Swift. While he was performing a litany of dialectical moves to try and fit it all together, I wanted to shout at my laptop: “because Said wasn’t really a radical!”

Re: Conrad - you mention in a footnote that you’ve read all the major Conrad works. Having read no Conrad at all, I was wondering: what are the major works? Where should I begin?