A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

My forthcoming novel about love, art, magic, and death, Major Arcana, drops later this month, on April 22. You can pre-order it here in print, ebook, and audio book formats (the audio book will be released on May 201), but, if you order directly from the publisher, you will even get a discount, and if you’re wondering what it’s all about, the interview at the link in Anne Trubek’s Note below will explain all:

In a mere 11 days, I will also be appearing at Riverstone Books in Pittsburgh’s storied Squirrel Hill neighborhood for the novel’s release event on April 17. The event is free: please register here! I hope to see as many people as can make the pilgrimage to what the novel calls “Steel City.” I will have other events, both online and IRL, to announce in support of the book soon. Thanks to all who have preordered the novel, reviewed it, supported it during its serialization, or, frankly, done anything else for the arts in America!

This week I also posted “As in a Dream” to The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. The first of a two-part episode on Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, it contains many highlights, from my attack on the commonplace that Dostoevsky is a writer for adolescents2 to my reminiscences about a college class on “Madness and Madmen in Russian Literature,” from my attempts to explain the religious history of Russia to my perhaps offensive speculations on why the political left seems to have a peculiar sympathy for the violent criminal. Thanks to all my paid subscribers! Coming up in the next several months we will finish with Dostoevsky and then add Tolstoy, Chekhov, Ibsen, Proust, Rilke, Kafka, and Borges to our ever-expanding archive (which also includes 46 episodes from 2024 on modern British and American literature) before enjoying a summer of Shakespeare and Milton and an autumn of great American novelists from James and Twain to DeLillo and Morrison.

I’m going to keep it brief today, because I will be annoyingly ubiquitous around Major Arcana’s release, and because I already have one or two pieces forthcoming from other venues next week.3 For now, a paragraph or two on—

Higher Level: The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Replaceability

Don’t worry, this isn’t another round of A.I.-in-art discourse—I know, I know: some of you think this is a flash-in-the-pan of no consequence for serious people, and some of you think the very apocalypse is descending—but let’s start here:

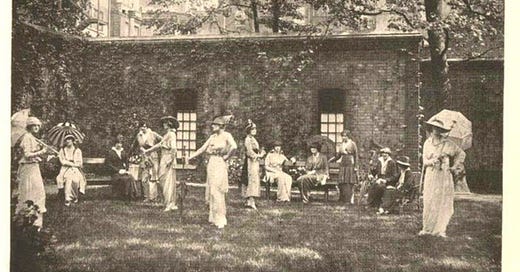

Or let’s go back to Hollis Robbins’s piece about how every university administrator needs to ask what departments and faculty can offer that machines can’t.

When I wrote about Tolstoy’s What Is Art? in the summer of 2020, I was so appalled by his puritanical vision, and so concerned to use my own essay as an encrypted polemic against the political tenor of that fiery season, that I think I forgot to mention my essential agreement with our great-bearded Russian prophet, himself walking in the footsteps of tedious Aristotle rather than visionary Plato: not to slight the intellectual element, which for Tolstoy is mainly ideological, but the primary purpose of art is emotional. Its social function, to put it in the New Age terms both deployed and satirized in Major Arcana, is to raise the collective vibration. All other defenses of poesie founder on the fact, whether we like it or not, of cultural relativism and historical perspectivism. Art incarnates social, moral, and religious truth? But these change from season to season, let alone century to century. Art, as Hegel and Baudelaire (odd pair!) agreed, just becomes the most vivid evidence for historical change itself; an education in art is an education in feeling one’s way into the work’s moment the better to experience the primary emotion, whether robed in peplos, kyrtle, ruff, crinoline, or whatever.4 The paradox of this realization, however, is that artists almost immediately took it to mean that art should be stripped bare, or, as I like to quote from “Ellen West,” a poem about how modern art is the same as anorexia, a divestiture of the flesh,

—Is it bitter? Does her soul tell her that she was an idiot ever to think anything material wholly could satisfy? ... —Perhaps it says: The only way to escape the History of Styles is not to have a body.

In other words, in a richly satisfying paradox, if you start at Aristotle—art is to express emotion—you will end up back at Plato—art is to commune with the formless forms, to enter the place beyond heaven and get married to God. The underlying logic of historicism discovered or invented in the 19th century, I believe, and not the oft-mentioned development of technologies like photography and cinema, is why painters started painting blank canvasses and novelists started writing novels without plots. (As for poetry, I discussed this when I wrote about John Ashbery, for example.) Photography and cinema didn’t help, though, or maybe I mean they didn’t hurt. Let’s say the most dramatic A.I. developments prove unstoppable5—what will it leave the author, the artist, the educator to do? Or what will it leave us to work with? In some ways, riding Ellen West’s train of thought, we might experience it as a liberation: with all styles instantly accessible and reproducible, history is abolished, and with it the body. All that remains, then, will be human consciousness, human personality itself, if only as the mysterious ingredient (we will say “made with love,” as of a pie) for which the high-end consumer will be willing to pay a higher price. Will this be a utopia or a dystopia? Well, if we could tell one from the other, would the last two radical centuries of dystopian utopias and utopian dystopias have happened the way they did once we decided to launch ourselves free from tradition once and for all?

If I were at liberty to tell you about my phone conversation with the producer of the audio book, you wouldn’t believe me, but let’s just say magic is real, and it is everywhere.

I will repeat here part of what I said in the episode on this subject: I was happily reading Nabokov, Chekhov, and Tolstoy in my teens but couldn’t comprehend Dostoevsky at all until I was about 25, because he requires more, not less, contextualization in the history of ideas, culture, and literature and therefore demands a more, not less, mature reader. By now he may be my favorite of the Russian writers for the daemonic energy of his dramatizations and the almost un-novelistic grandeur of his characters; I will concede to his detractors, however, that the Christian moralizing and the habit his characters have of “sinning their way to Jesus” (Nabokov’s phrase) do grow tiresome.

I’m not complaining, only observing—in fact, I am grateful—that for over 10 years I couldn’t get anyone at all to reply to my emails, and now I can barely keep up with commissions and requests. In re: recent gender-in-literature discourse, those shadowy metaphysical forces in Mulholland Dr. who said, “This is the girl!,” really did put out the call last year, “Bring back the men!,” didn’t they?

Someone was asking me indirectly about tariffs. I don’t know anything about tariffs. My heuristic, not to be excessively provocative, is that when the expert class is melting down about something, they’re probably wrong, because they have been catastrophically, even murderously, wrong about everything that has mattered most for this entire century. (I don’t mean to alarm anyone, but we have not yet begun to take the measure of the staggering damage these experts may well have done.) But who knows? Maybe this is really the big one, the end of everything. I did make the point that opposing free trade and the resulting circulation of cheap consumer goods made by semi-coerced and under-remunerated labor was initially the left-wing position, as in Ruskin’s “Work of Iron,” a founding text of English socialism:

For, to take one instance only, remember this is literally and simply what we do, whenever we buy, or try to buy, cheap goods— goods offered at a price which we know cannot be remunerative for the labour involved in them. Whenever we buy such goods, remember we are stealing somebody’s labour. Don’t let us mince the matter. I say, in plain Saxon, STEALING—taking from him the proper reward of his work, and putting it into our own pocket. You know well enough that the thing could not have been offered you at that price, unless distress of some kind had forced the producer to part with it. You take advantage of this distress, and you force as much out of him as you can under the circumstances. The old barons of the middle ages used, in general, the thumbscrew to extort property; we moderns use, in preference, hunger or domestic affliction: but the fact of extortion remains precisely the same. Whether we force the man’s property from him by pinching his stomach, or pinching his fingers, makes some difference anatomically;—morally, none whatsoever: we use a form of torture of some sort in order to make him give up his property; we use, indeed, the man’s own anxieties, instead of the rack; and his immediate peril of starvation, instead of the pistol at the head; but otherwise we differ from Front de Bœuf, or Dick Turpin, merely in being less dexterous, more cowardly, and more cruel. More cruel, I say, because the fierce baron and the redoubted highwayman are reported to have robbed, at least by preference, only the rich; we steal habitually from the poor. We buy our liveries, and gild our prayer-books, with pilfered pence out of children’s and sick men’s wages, and thus ingeniously dispose a given quantity of Theft, so that it may produce the largest possible measure of delicately distributed suffering.

But the left gradually reoriented itself from defending the dignity of the producer to enshrining the desire of the consumer. British radicalism, for exampled, moved from Carlyle and Ruskin, who now sound simply and horrifyingly fascistic to us, like straight-up Nazis, to Wilde and Woolf, our queer heroes, with their anarchic mobility of personal identity and aesthetics, until we arrive here in America, to take a later instance, at the essays, early and late, of a feminist socialist critic like Ellen Willis (not West), who wrote this as a young radical in 1970—

When a woman spends a lot of money and time decorating her home or herself, or hunting down the latest in vacuum cleaners, it is not idle self-indulgence (let alone the result of psychic manipulation) but a healthy attempt to find outlets for her creative energies within her circumscribed role.

—and this on her deathbed in 2006—

Another left rationale for rejecting cultural politics is rooted in the historical connection of cultural movements to the marketplace. The rise of capitalism, which undermined the authority of the patriarchal family and church, put widespread cultural revolt in the realm of possibility. Wage labor allowed women and young people to find a means of support outside the home. Urbanization allowed people the freedom of social anonymity. The shift from production- to consumption-oriented capitalism and the spread of mass media encouraged cultural permissiveness, since the primary technique of marketing as well as the most salient attraction of mass art is their appeal to the desire for individual autonomy and pleasure and specifically to erotic fantasy.

Accordingly, left cultural conservatives have argued that feminism and cultural radicalism, in weakening traditional institutions like the family, have merely contributed to the market’s hegemony over all spheres of life. Many leftists, including Frank, see the cultural movements through the lens of their hostility to consumerism: observing that commercial exploitation of sex is ubiquitous and that rock and roll, feminism, and other countercultural artifacts have been used to sell everything from cars and fashions to credit cards and mutual funds, they conclude that cultural liberation, like the backlash against it, is a tool of capitalist domination.

—both of which tend to imply that, while the dignity of the producer should be protected as far as possible, the liberation of the consumer is something like the liberation of marginalized subjectivities tout court inasmuch as consumerism is how they materialize their previously suppressed desires. (See also the canonical essay in queer theory, John D’Emilio’s “Capitalism and Gay Identity,” which makes a similar case.)

I don’t raise these points to advance an argument. I have no argument in this area. My main argument about consumerism is that you really ought to buy my book and subscribe to my podcast. The conflict between production and consumption and the divergent values they imply seems to me to be a genuine conundrum, exacerbated by everything from the fact that I myself am a consumer to my core or coeur and that Woolf’s inexorably death-tending aesthetic nihilism portends the end of civilization itself in an access of “shop-till-you-drop,” or, rather, drown. To be fair to Woolf, she does enshrine the producer, but in her case, as in mine, the only producer she can imagine is the autonomous artist: the interior decorator trapped on the inside of the consumer society rather than its external fashioner. And then we haven’t even considered the real elitist position, namely, that even the productive workers are only “hands,” instruments for the real archons of our earth, the owners and technocrats.

(For more on these questions in their literary-historical dimension, please visit the Invisible College archive and listen to the episodes on Tennyson, Dickens, Shaw, Wilde, and Woolf.)

As for state of the intellectual left today, it appears to remain in disrepair if this recent New Republic essay on Sebald is anything to go by. A beloved novelist’s early academic essays on Austrian literature, which sound like jargon-choked Frankfurt School stuff, turn out to have lessons for us (imagine this!) about Trump, climate change, and, most amusingly, billionaires. (Billionaires are not the villains in Kafka, it should go without saying, who is the subject of the paragraph where the billionaires show up. And, though the New Republic essay is only seven days old, the billionaires have already changed sides, because they don’t like—tariffs!) Anyway, Sebald himself appears to have had a change of heart between when he was writing his academic essays and when he was writing his novels, because the latter, as I discuss in my essay on The Rings of Saturn, are works of apolitical nihilism reducing human to natural history, sort of itself a fascist gesture, at least if we follow Arendt. (Admittedly, I still need to read The Emigrants.) On that note, when I imagine our apparently oncoming future when World War II no longer grips the imagination as the origin story of our political and cultural ethics, worshipful of the otherness fascism sought to destroy, I am afraid of the consequences, afraid we will simply worship force, but I am also, I confess it!, a little bit relieved that essentially metaphorical uses of the word “fascism” like the following will be retired from arts criticism, which it has mightily distorted by associating all beauty and order and sublimity and genius with an urge to dominate and annihilate—

As importantly, in highlighting these Austrian novelists, Sebald here is calling for a kind of art that resists the desire to be complete, to be perfect, to be ideal—for in this lies, he suggests, a similar impulse to fascism. “The invariability of art is an indication that it is its own closed system, which, like that of power, projects the fear of its own entropy on to imagined affirmative or destructive endings,” he remarks, adding that “already in the great symphonies one hears, in the final notes, the desire for destruction.”

—since from this point of view, as Adorno’s Minima Moralia distinctly implies in its aphorism on time (see here), even to exist at all is fascist because it means we occupy space that might have been occupied instead by the holy other.

Someone recently described me as optimistic about technology. It’s probably true that I have recently tried to offset the literati’s fashionable techno-pessimism out of sheer desire to be contrary, and also out of my characteristic impatience (see footnote 4 above) with the intellectual left: “Oh, now, when it’s your job on the line, you suddenly know what nature and the soul are? Get out of here!” But my position is not really optimistic. I agree with techno-pessimist novelist Ewan Morrison in this recent episode of the Madness and Method podcast when he says that two techno-dystopias are descending on the planet: a mixture of Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four on the Old World and Neuromancer on the new. I only sound optimistic because I think, as far as dystopias go, that Neuromancer is a hell of a lot better than Brave New World plus Nineteen Eighty-Four, and so I am relatively grateful I get to live in the American rather than the Euro-Chinese dystopia. You can tell my judgment is not eccentric because readers and audiences have always fantasized about what unwholesome fun it might be to live as noirish cyberpunk samurai-cowboy-detectives in the rainy polyglot megalopolises of Neuromancer and related texts (Blade Runner, Akira, Ronin, etc.), whereas nobody actually wants to reside in Orwell’s or Huxley’s fictions. (Well, and see footnote 4 on consumerism, people do want to live in Huxley’s, maybe even most of us secretly do, but they/we don’t describe it to themselves or ourselves as dystopia. As for Orwell’s, one consumer tweak would go a long way in making Ingsoc literally palatable: a little fat, butter, or oil, albeit not seed oil, to sauté rather than boiling the cabbage. )

Reading, of all things, Harpo Marx's autobiography I really got a good sense of how vulgar, soulless, and anti-human the advent of film must have seemed to people in vaudeville. And they were right, it really did lead to the complete destruction of a great tradition of indigenous art which is now lost forever. But hey, we got some good stuff out of the results! I don't know if we're in a similar situation (certainly the people in charge of the technology now frighten me much more than say, David O. Selznick!), but it did calm me down a bit to think about.

I finished it. Working on my review for Locus now (published in the June issue). I didn’t expect it to be so moving. I wouldn’t have guessed it from here, but you’re a softie. It’s also one those novels where people will take different things from it depending on where there interest lie. It has multitudes.