A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I released “Let the World’s Great Order Be Reversed” for The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. It’s about the radically conservative comedy of Aristophanes and the conservatively radical tragedy of Euripides, and it illuminates via these ancient texts many a dilemma of the writer in our own time, bewildered as they were and as we are in a political and spiritual chaos. Next week: Plato promises to bring order—but can he succeed? Please offer a paid subscription today to find out, and many thanks to those who are already matriculates in this most independent of academies.

I remind you as well that my new novel, Major Arcana, will come with the spring. Belt Publishing releases this decades-spanning cross-country epic of low culture and high magic on April 22, 2025. Please pre-order Major Arcana here if you would like to encourage publishers, like the broad-minded Belt, to take risks on challenging fiction, and also if you’d like to enjoy the book Ross Barkan has labeled “the elusive great American novel for the twenty-first century,” Bruce Wagner has hailed as “a bravura, hallucinatory tarot of art, madness, and the fatal poignance of being alive,” Kirkus Reviews has judged “a rich and enriching novel,” and Publishers Weekly has deemed “morbid and digressive.” (I want that last one on a T-shirt.)

For today, a few incendiary remarks, in the main text and the footnotes. Partly I play the hits; partly I offer some new thoughts. You probably shouldn’t read it. Please enjoy!

Soph Power: Art After the Regime

Way back in 2019 I wrote a review of a then-recent leftist academic book (Harvard UP) claiming that the American literary scene has been stultified and strangulated for decades by the state. This happened and goes on happening not via the direct interference of an agency like the CIA, as famously publicized in books like The Cultural Cold War, but by the CIA’s much subtler successor: a dense network of interlocking foundations and academic institutions laundering government money to fund what the author, concerned with racial justice on an old Marxist or Third-Worldist model, called “state-sponsored multiculturalism” and a “State Department version of what matters.” This state-foundation-academia nexus brain-drains the country’s creative spirits into normalizing institutions like MFA programs, crowds out the independent publishing that fueled past radical artistic and political movements from Gertrude Stein to Amiri Baraka, and elevates middlebrow moralistic pabulum in elite publishing over artistic experimentation and political radicalism. In the background is a cognate argument about the similar use of NGOs and other cut-outs to launder U.S. government interference, usually through astroturfed liberal movements within “independent civil society,” in the sovereignty of any country whose leaders, elected or otherwise, wish to possess their nation’s resources for the nation.1 The author concludes with a call for a “revolution” to break the deadlock effected on American literary and indeed political life by this liberal empire of lies. I mention it because—well, why do you think I mention it? And did you really think it could go on forever?

The revolution is here. Or perhaps the counterrevolution. The far left’s dreams came true, with a predictable be-careful-what-you-wish-for twist. It feels like the last days of the Soviet Union, not the first. And yet, in my 2019 review—2019 feels less like seven than like seven million years ago; I had already soured a bit on the left, but had no idea what 2020 and 2021 would bring—I criticized the author for confusing artistic and political experimentation. They do seem now to be co-extensive in my experience, however. The U.S. is in the first truly revolutionary situation of my lifetime even as American literature feels more alive than at any time this century. Brother Gasda, who promised us we’d be Emersonizing the eschaton this year:

What are we realizing now? That progressivism was an enforced set of unneighborly,2 toxifying beliefs perpetrated by NGOs and corporations that wanted to cover their bad behavior. Millions of young people turned on their family, their friends, their neighbors, their teachers because they believed that the moral arc of the universe was ecstatically close to the end of history, to liberation… and that only a few bad people—horny people, aggressive people, beautiful people, negative people, tribal people, tribalistic people, prosperous and successful people—were in the way; that you could go about conducting yourself in this alienating and violent way, that you could participate in a covert cultural revolution because the ideal end was near (and that the main thing you had to do besides destroying the Enemy was promote your own decency and joy and forward-thinkingness on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter).

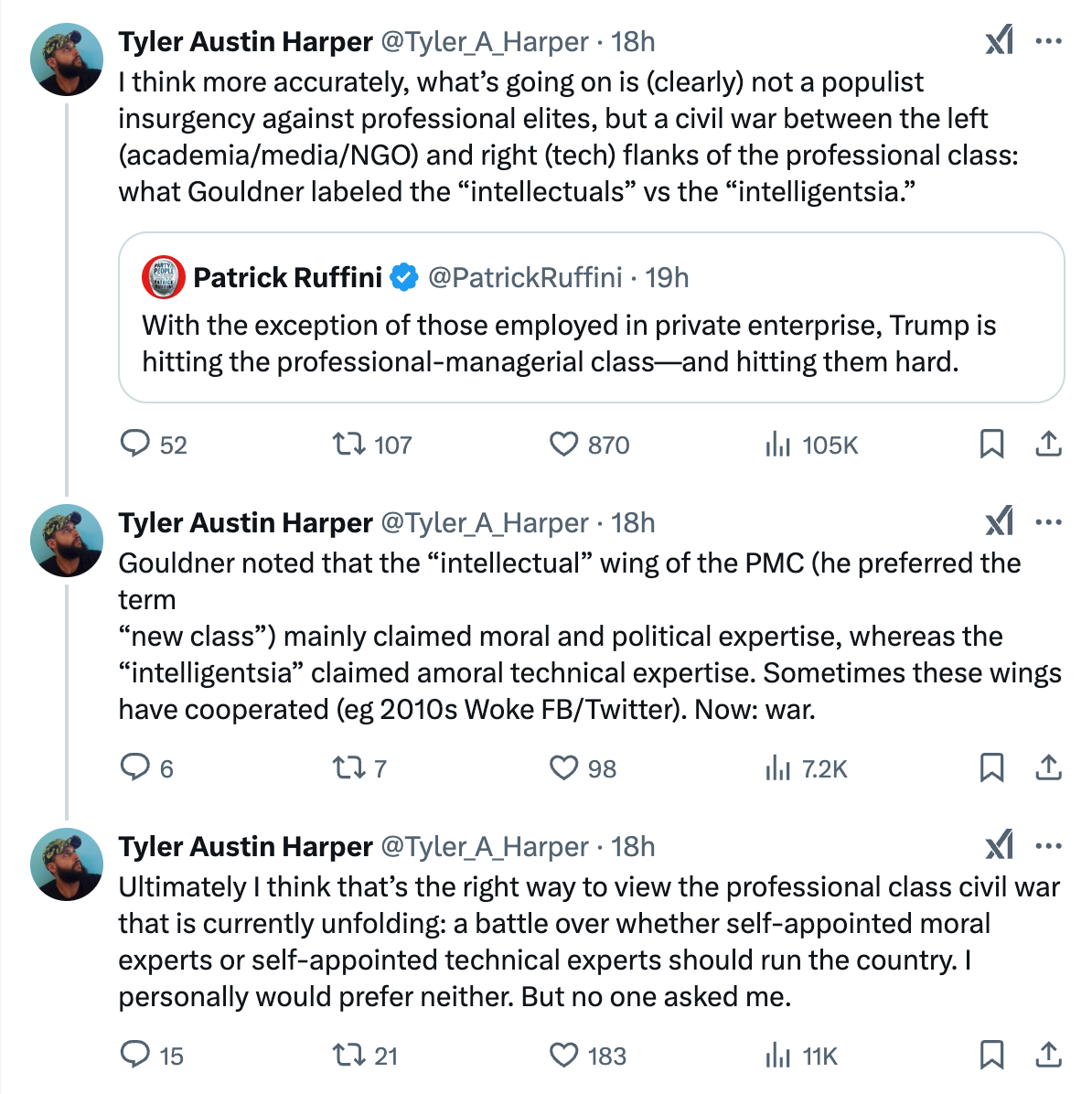

Please don’t mistake my comments for naive enthusiasm. I am fascinated only by the opportunities a moment of chaos may engender. (Easy for me to say as I am now mostly untethered—not by choice, in my defense—to the affected institutions.) It will probably only be a moment, however. We find ourselves either between an old and a new regime, or in a hiatus of the old regime’s power, which it may somehow re-assume.3 Tyler Austin Harper crisply characterizes the contending parties:

I would also very much prefer neither, my years of rudely rebuffed attempts to join the intelligentsia, indeed to save it from its current predictable disaster, notwithstanding.

Preferring neither regime of technocracy has consequences of its own in the artistic life, however. The civil war in the literary world, centered on the merit or demerit of this very platform, is about the “old guard” of writers—old in their allegiances, not in their ages; Becca Rothfeld, for example, is 10 years my junior—who belong or aspire to belong to the intelligentsia, and the “new guard” who see that the intelligentsia’s proverbial gravy train has been derailed and who are therefore compelled, whether they (we) like it or not, to think of ourselves not as a publicly funded clerisy but rather as artistic entrepreneurs—not as Platonic philosophers rationally ruling the polis from a position of state-protected authority but as scarcely defended and freebooting Sophists vending instruction and delight in the chaotic marketplace.

If we are in the latter category, however, and in deference to the Marxist theory of the way these things work, we will, if we are being honest, have to contemplate our true politics.4 I recall the post-election Substack post about how podcasters and Substackers, as petit-bourgeois5 small business owners, were structurally aligned with MAGA. True, I thought, but how you can be so high and mighty about it when you’re here selling your trinkets with the rest of us?6 This is not to say our chosen artform has no inherent design on the polis, no inherent politics of its own, such that we should change sides without conscience every time there’s an election, only that our priority must be how best to materialize our actual will in our actual situation. We make history, as the poet said, but not in circumstances of our own choosing.

The aforementioned Sister Rothfeld lucidly summarizes Schiller on the true politics of Romanticism—

If the political is aesthetic, is the aesthetic political? For Schiller, the answer is a tentative yes. Aesthetic success is a prerequisite for political success, because only people perfected by encounters with beauty are “ennobled” enough to embrace the dictates of an enlightened government.

—that vision of (in Stevens’s phrase celebrating and rueing Shelley) “[a] time in which the poets’ politics / Will rule in a poets’ world,” a loose and classless republic anti-governed by artists themselves under the anti-rule of the ludic drive. Rothfeld associates this, and Shelley would agree, with Platonism, but to my mind it’s a Platonism in spirit rather than in letter, and that’s if Plato was not himself being ironical. But such an ambition goes back a long way, into unrecorded time. Literature—or perhaps we had better say art—is not so much a false god as the incomplete and ongoing scripture of a very, very old religion, which also promises to be the religion of the future: a religion much older and much newer than the Platonic-Judaic-Christian-Marxist attempt to encompass and subdue it, with the added irony that the Platonic, Judaic, and Christian scriptures themselves belong to art, and that Marxists have written some of the most intelligent commentary on art.

Our credo, whether we know it as our credo or not, has survived many an upheaval and seen off many a rival; I have every faith it will likewise survive the defunding of the institutions that claimed us as dependents and therefore left us in a state of self-imposed minority7 for the last half century.

Here the irresolvable problem of “democracy” opens before us. Everyone likes democracy until 1. the demos chooses something that offends or threatens them; and/or 2. they get their own preferred unaccountable authority into power. Liberals have squandered their defense of democracy in recent years by defending in democracy’s stead the bureaucratic technocratic oligarchy both Marxists and right-wingers of various stripes correctly identify to be operative in elements of “post-World-War-II international order” and “end of history” governance; but, in fairness, liberals’ commitment to minority and individual rights means that liberalism cannot hold sacred the sometimes prejudiced or benighted decisions of the demos. As John Stuart Mill points out, we can be tyrannized by the majority as easily as by a king. For their part, Marxists have long allowed the necessity for a tyrant—in the neutral sense of a non-hereditary figure fulfilling the function of a monarch—to operate as a hammer on behalf of the people’s will, whether people themselves consciously understand this will or not, thus concepts like the dictatorship of the proletariat and the sovereignty of the Party. (I am reading the chapters on the Greeks in Russell’s History of Western Philosophy to prepare for upcoming Invisible College episodes, and he makes clear that in the ancient world democracy and tyranny were in this sense allied to each other against aristocracy, oligarchy, theocracy, and hereditary monarchy. That democracy is not opposed to tyranny but is rather its logical precursor will also be a central claim of Plato’s Republic.) Both the center-left and the far-left can usually be found, then, in the embarrassing posture of defending various forms of undemocratic power. The nominally populist right supporting Trump, for their part, is in the same position as the Marxist Caesarists, thought it should also be said that the popularly elected sovereign’s seizing full control of the executive branch is one of the most literally democratic things to happen in recent politics.

“Neighborly” is a good word for what was lost. The woke era in the mainstream arguably began, somewhat contingently, with the center-left’s Civil War fixation, launched at The Atlantic, as a replacement “good war” to legitimate liberal imperialism after the neocons tarnished WWII with overuse (Islamofascism, Saddam = Hitler, Iran = Nazi Germany, etc.). Liberals have historically preferred, however, to de-emphasize the Marxist insistence on the need for “a war inside society” and to enshrine in its stead the utopian socialist ideal of a society progressing together by the mechanism of civic deliberation toward immanent fulfillment. They have done so because civil war, the literal slaughter of your neighbor, is so viciously appalling it should only be considered as a last resort, not something casually promoted in a nominally moderate organ. The un-neighborliness of the 2010s spread into every area of life, making art and thought difficult with its prohibition on the disinterest necessary to the artist or thinker who must represent or conceptualize everything without immediate resort to peremptory judgment. I quote (see footnote 1) from Russell’s History of Western Philosophy for what we might call neighborliness—a measured generosity, tempered by an awareness of boundaries—in thought, the very habit of mind forbidden by the endless-civil-war mentality:

In studying a philosopher, the right attitude is neither reverence nor contempt, but first a kind of hypothetical sympathy, until it is possible to know what it feels like to believe in his theories, and only then a revival of the critical attitude, which should resemble, as far as possible, the state of mind of a person abandoning opinions which he has hitherto held. Contempt interferes with the first part of this process, and reverence with the second. Two things are to be remembered: that a man whose opinions and theories are worth studying may be presumed to have had some intelligence, but that no man is likely to have arrived at complete and final truth on any subject whatever. When an intelligent man expresses a view which seems to us obviously absurd, we should not attempt to prove that it is somehow true, but we should try to understand how it ever came to seem true. This exercise of historical and psychological imagination at once enlarges the scope of our thinking, and helps us to realize how foolish many of our own cherished prejudices will seem to an age which has a different temper of mind.

Likely the former. Astrological science (Bertrand Russell spins, rolls, quakes, and veritably vomits in his grave) designates the coming age one of decentralizing and dispersed authority, collective and individual revolution. Some kind of network-state “patchwork”—to use the neoreactionaries’ preferred nomenclature—is probably inevitable, if only because of the technological situation. The “tech right” has temporary allied itself with religious conservatives and nativists to throw culture-war red meat to the people to disguise the actual transformation underway, a transformation whose pragmatic effect will be the further destabilization of the national populace and of gender roles. The so-called “chuds” will get their moment in the sun to hate Indian programmers and trans women, and then an Indian trans woman will be reprogramming their neurolink while Curtis Yarvin looks on smiling. As with the Reagan revolution before it, the Trump revolution’s cultural conservatism may prove short-lived, a little carnivalesque relief of social pressure, while its alteration in the balance of economic and technological power will last long—an ironic victory, as some have theorized, for “the deep left.” Which has broadly been my argument for over a decade. I wrote this in 2014: a prediction not only that the hegemony of neoreaction would succeed the hegemony of social justice, but also that they share crucial commitments in common. (I spun this take esoterically out of a reading of Ulysses, by the way, that all-encompassing and infinitely prophetic Bible of our modernity.)

Speaking of artists who sought a brutally honest alliance with capitalism… “Hate listen” is too strong a term to apply to people who seem very nice and very smart, but the Know Your Enemy podcast is a “mild irritation listen” for me. They just seem like they’re in the wrong century or several—the social-democratic 20th, the Marxist 19th, the Christian first—and not in a “wrong side of history” way, just in a “you think you’re fighting, but you’re not even on the battlefield” way. Anyway, their recent pod on Ayn Rand convinced me that my longstanding approach of staying away from Rand because I will probably like her if I don’t remains sound. Of course she thought she was a rationalist, like Bertrand Russell, while I am certainly of the other party there; her derogation of pity per se is sound, however, as pity is an appropriate emotion to feel for babies and birds but not for fellow adults. Anyway, Adler-Bell strayed onto the battlefield when he observed inter alia that Rand was merely applying the mentality of the modern artist not only to art but to everything else. Which is to say, she dreamed of a time in which the poets’ politics will rule in a poets’ world. (She and Stevens even had essentially the same political outlook.) The replacement of reality by human consciousness, potentially to include human consciousness’s custom-built successor of machine consciousness, is the issue now, almost the sole issue, lurking behind all our superficial political battles, a lesson the untimely imaginative writers of the Marxist 19th and social-democratic 20th century still have to teach us now that Marxism and social democracy are gone.

Longtime readers will recall my thesis, also primarily derived from a reading of Ulysses, that the petite bourgeoisie, because it has been one major if disavowed fount of modern art, is what Marx thought the proletariat and Gouldner thought the PMC were: a universal class with the potential to lead the whole of the polity, including all the other classes, to truth and beauty.

The question of identity politics in this matter, however, is more complicated than it appears. One will stand accused of wishing to reestablish some kind of white-male hegemony upon the vanquishing of state-sponsored literature and its “diversity” criteria. Yet on the capitalist side we find the empire of books now expanding thanks to the oft-disparaged female readership and its oft-disparaged taste. Such taste, whether we like it or not—I think it has its good points—may for now keep the whole enterprise afloat.

Sam Kriss surveys one consequence of this minority in his circumspect review of the new and independent literature’s first stirrings: an inability to write beyond the self. (Please note from my own review of Levy and Cash that the self speaking in the former’s fiction may very well [allegedly] be the self not of the author but of her machine collaborator.) In pursuit of the argument that imaginative writers descend from Sophists rather than Platonists, I was perusing Simon Critchley’s Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us of 2019; I admired aspects of the argument, but I kept running into Critchley’s irritating insistence on defining human life by our shared experience of weakness, need, and vulnerability, now a staple of leftist rhetoric. I don’t only object to this now commonplace leftist line—how different from Marx’s Prometheanism!—simply because it evinces the intelligentsia’s transparent political stratagem to render individuals helpless and in need of endless and total state governance under the intelligentsia’s authority. I also dislike it because what we share in common is the least interesting thing about us. Our unique strengths are better worth discussing than our common weaknesses, because only our unique strengths and not our common weaknesses will free us from illegitimate or even just unwanted authority. All unhappy families are alike, as the totalitarian puritan Tolstoy did not say, but every happy family is different. Udith Dematagoda, in his polemic against Rothfeld, identifies another stratagem at work in writing the vulnerable self, one related to the autofiction Kriss demotes:

When a writer intentionally intertwines the substance of their dubious intellectual project with the uncomfortable and awkward minutiae of their personal life, they have, in my view, rather cynically created a cordon sanitaire around the former, one which threatens to erase the distinction between criticism as an intellectual activity, and criticism as mere personal invective.

These are perhaps matters of temperament, however; one either finds a personal rhetoric compelling or one doesn’t. Another writer I follow on here, a writer who has nothing temperamentally in common with Dematagoda or Rothfeld, movingly describes her intention to use her personal experience to testify against the potentially calamitous medical consequences of the intelligentsia’s defeat. I am, for better or for worse, at one with the impersonalists. Perhaps this is a loss, mine or yours, but here we are. As the man who serves (pace Juliana Spahr) in all the best and all the worst ways as our Amiri Baraka was recently pleased to put it,

Late Soviet does feel like the right comparison. I've been thinking a lot about not just Gouldner but Kojève's equivalence between the postwar US and USSR lately, and wondering if this isn't just the other foot dropping after forty years, the beginning of the disarticulation. As a Platonist-Christian and a sort-of product of the downwardly mobile managerial-clerical class I don't and possibly can't agree with your precise conclusions, but I think your tone is close to the truth than brother Gasda, who has lately been seeming to me altogether too sunny in his evaluations of the state of things.

*cough* For Gouldner will fight, and Gouldner will be right.