A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I released “The Brain Is Wider Than the Sky,” an episode on the poetry of Emily Dickinson, for The Invisible College, my series of literature courses for paid subscribers. This is either one of the best or one of the worst episodes I’ve ever posted, depending on what kind of literary discourse one thinks is best suited to the podcast format. Sometimes I am able to able to produce a pretty smoothly narrated high-level overview of an author, as in episodes you will find in the archive on Shaw or Lawrence or Emerson or Thoreau, but at other times, as in this Dickinson episode, such a discourse would be false to the nature of the subject, or more false than usual, so I simply wrestle “on air” with the strangeness and difficulty of the work under discussion. Dickinson’s brain is wider than ours, and I thought it honest to show what such breadth means for a reader of her poetry. Come for my struggle with our post-Puritan poet’s cracked hymns and stay for my concluding discussion of Robert Graves, Camille Paglia, and their conflict over whether straight men or lesbians make the best poets. And next week, speaking of a conflict between straight men and lesbians, we will consider, just in time for the election, perhaps the all-time novel of the American culture war, Henry James’s The Bostonians.

Another novel of the American culture war—though also about much, much more besides—is my new and forthcoming Major Arcana. I remind you that you can pre-order it here, get it from NetGalley here, and access the original Substack serial as a paid subscriber here. This tale of the occult—“a hallucinatory tarot of art, madness, and the fatal poignance of being alive,” per the novelist and (horror) screenwriter Bruce Wagner—is also eminently Halloween-appropriate. I direct you in this most frightening season to the only chapter of the serial I ever posted in its entirety for free, one of the novel’s darkest episodes, the most terrifying on a human as well as on a spiritual level, the chapter friend-of-the-blog and early reviewer Mary Jane Eyre understood as the narrative’s secret heart: “The High Priestess.”

For today, a response to Blake Smith and B. D. McClay on literary immortality, with footnotes on why I don’t think astrology can predict the election, why I hate The Substance, and why Soros funds Compact. Please enjoy!

Look on My Works, Ye Mighty: Striving for Literary Immortality

Should writers write for posthumous fame, for secular immortality? I am inspired to wonder by the little contretemps here on Substack between Blake Smith and B. D. McClay. Smith writes:

Alexandre Kojève, the brilliant interpreter of Hegel, insisted that in claiming to have arrived at Absolute Knowledge and the end of philosophy, Hegel was claiming to be God—and that he himself, in claiming to have understood Hegel, was likewise divine. However outlandish this sounds, it rightly expresses the outrageous pretension at the heart of any enterprise of explaining the world, much less one that purports to be the last and best. We should be equally alert—and grateful to Bloom for alerting us—to the grandiosity of the poet and the critic’s mission.

Polite writers may assure us that they do not care if they are read in two hundred years. We should, tipped off by Bloom, suspect that this is deceptive loser bullshit.

This reminds me of something I wrote about a year and a half and almost 1000 subscribers ago, when I was first serializing Major Arcana and still deep in the throes of its composition. I wrote:

By the time I’m done here, I want that tattoo on Lana Del Rey’s arm to read “Nabokov Whitman Pistelli.” I saw a Tweet this week from an artist who said he desired his name to disappear, his ideas to be plagiarized and stolen and disseminated anonymously, prolifically, with no author attached. I was moved by the nobility and high-mindedness of this beautifully post-egoic wish. But I would like intelligences made solely of light, on a planet circling a distant star,1 to flicker my name in their luminous language two billion years from now. Some of us are saints; some are sonneteers.

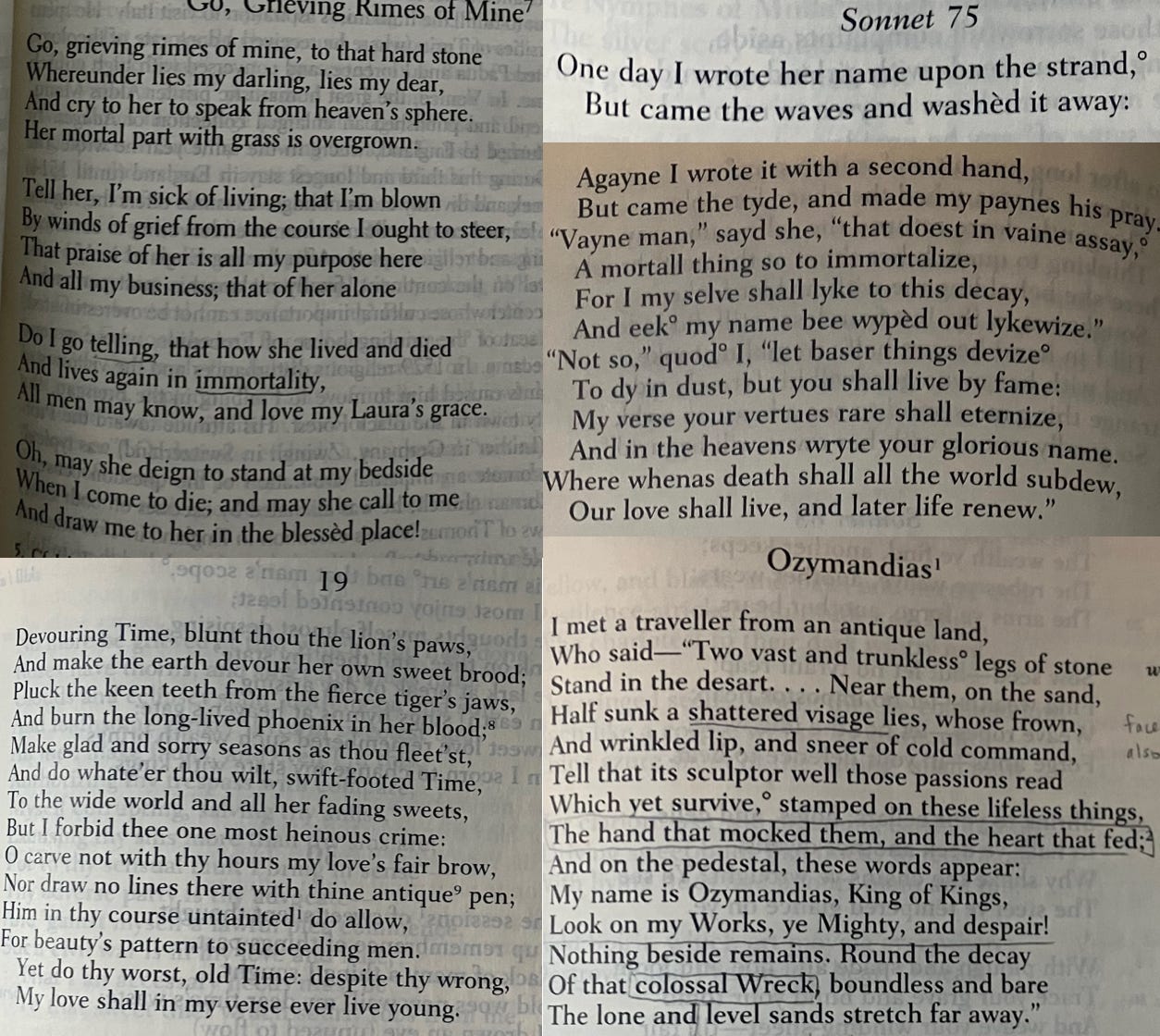

With the last word, I meant to summon the claim of writers of love sonnets like Petrarch, Spenser, and Shakespeare that their verse would immortalize not themselves but their beloveds. Bloom would tell us, I’m sure, that the stated desire to immortalize the beloved conceals (badly) the poet’s own disavowed desire for personal immortality. By the time we get to Shelley, notwithstanding his own many long-suffering and sometimes short-lived beloveds, we hear the claim stated outright that poetry per se will outlast empires.

A contemporary and acquaintance of Shelley’s, a fellow radical and Romantic, the critic William Hazlitt, wrote an essay on this subject: “On Posthumous Fame: Whether Shakespeare Was Influenced by a Love of It.”

The thirst for literary immortality, Hazlitt concludes, is the product of taste, not genius: education and a sense of belatedness produce it. The Greeks did not desire literary immortality because they did not know such a phenomenon was possible. Only the Romans, with the towering example of the Greek classics behind them, began to thirst for posthumous renown. Then, with Dante’s acute consciousness of his own great Greek and Roman precursors at the dawn of the Renaissance, poets and other writers started to work consciously toward the goal of a canonical afterlife. Hazlitt mentions Chaucer, Spenser, Bacon, and Milton as authors obsessed with posthumous fame; he implies, for example, that the unremittent sublimity of Paradise Lost derives from Milton’s intense consciousness of emulating the immortal classics and winning immortality in turn. But Shakespeare, Hazlitt argues, was different. Hazlitt anticipates Borges in judging Shakespeare “everyone and no one,” too un-self-conscious in his universality to care about the status, posthumous or otherwise, of his reputation. Shakespeare, we might say, had no taste, only genius:

To feel a strong desire that others should think highly of us, it is, in general, necessary that we should think highly of ourselves. There is something of egotism, and even pedantry, in this sentiment; and there is no author who was so little tinctured with these as Shakespeare. […] [M]en of the greatest genius produce their works with too much facility (and, as it were, spontaneously) to require the love of fame as a stimulus to their exertions, or to make them seem deserving of the admiration of mankind as their reward. It is, indeed, one characteristic mark of the highest class of excellence to appear to come naturally from the mind of the author, without consciousness or effort. The work seems like inspiration—to be the gift of some God, or of the Muse.

That is a rebuke of us sonneteers from the 19th-century radical Hazlitt worthy of the chastenings the 18th-century conservative Dr. Johnson liked to deliver. Johnson once wrote, in The Rambler No. 106, “No place affords a more striking conviction of the vanity of human hopes, than a publick library,” a library where we encounter a mass of mouldering and forgotten books. (How much better-stocked is the library of oblivion almost 300 years later!) Johnson could in some measure be judged the resentful Christian pseudo-loser the oft-Nietzschean Bloom liked to reprove—though Bloom personally deemed him the greatest critic in the language—and McClay, in her reply to Smith, not only echoes Johnson’s mood of humility but even quotes Ecclesiastes:

there is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after

for there is no remembrance of the wise more than of the fool for ever; seeing that which now is in the days to come shall all be forgotten

and how dieth the wise man? as the fool

thus you should strive to do the best you can to do the best work you can in the time allotted to you, with the understanding that it may or may not have any relevance outside the objectively small bubble that is your lifespan and whatever that life immediately touches

Surely Hazlitt is correct: we should thank the Muse, not ourselves. Johnson, McClay, and the preacher of Ecclesiastes also have it right; as Woolf’s Mr. Ramsay laments, “The very stone one kicks with one’s boot will outlast Shakespeare.” On McClay’s last point, however, the one about “striving,” I would make my own case for the “immortality” incitement to literature, since I seem to feel it so strongly, if self-parodically, myself.

Before I do, though, let me acknowledge that the immortality motive does pose risks to the individual talent. Hazlitt suggests one when he refers to Dante and Milton, who were so self-consciously epic, as Homer was not, or as there was not quite any “Homer” to be. To be motivated by immortality is often to try too hard. Many a would-be Great American Novel is immured in its too-witting attempt to be great. Isn’t this why many readers of Philip Roth, for example, prefer the violently disreputable Sabbath’s Theater to American Pastoral, that better-behaved bid for the canon?2

Another danger, this one specific to the novelist: the consciousness of far-future readers may cause one to shy away from specificity, to resort to allegory or symbolism rather than to plunge into the life of your time for fear it will proved dated. I had to banish this fear when I wrote Major Arcana, with its superhero comic-book writers and nonbinary YouTube influencers and the like. I am wary of the drive to allegory in contemporary fiction, the long shadow of Kafka. (But such tends to be the preference of the Nobel Prize committee, the surrogate of literary immortality on earth, since those presumptuous Swedes often must read in translation: allegory travels well across the barrier of language as across the gulf of time.3) Nevertheless, canonical literature offers a comforting example here. Think of how much trivia Dante and Joyce have forced us to know about their hometowns circa their adolescence and early adulthood. Sometimes, just as the sonneteers claimed, literature really does immortalize the object of the writer’s concern as it immortalizes the writer.

In the two centuries since our radical critic wrote, however, Hazlitt’s Romantic recommendation of spontaneous effusions has become a trap of its own, the Romantic common-sense of a writing pedagogy that often favors process over product and therapeutic self-expression over the creation of the artwork. It’s true that when we imagine the adoring eyes of the future on our performance, we may behave with excessive hauteur, as the epic poets of the second millennium anno Domini arguably did. But it’s also possible that imagining a monitory eye trained on us from further millennia may at least inspire us to behave with the dignity befitting poets who write for an audience well beyond our small and sole selves.

In other words, the very consciousness of our minority recommended by the chastening preacher—vanity of vanities, all is vanity!—may be just what we need to make ourselves major. Out of humility, pride. As the God of modernity, Goethe’s God in Faust, liked to say, and as I like to quote: All who strive can be saved.

Speaking of stars, readers may recall that I spent some time this summer trying to use the presidential election as a test of what they call mundane astrology, that is, the use of astrology to predict events in public and political life. (This is the aftermath of the occult researches I undertook for Major Arcana.) The YouTube astrologers acquitted themselves beautifully a few months ago. They clearly read into Trump and Biden’s birth charts that the one would be in danger and the other would be in abeyance in the month of July, which is exactly what happened. More recently, however, I have concluded that we probably can’t use astrology to predict a vast and contingent human event like a U. S. presidential election, for the same reason we can’t meaningfully use (e.g.) Nate Silver’s scientific method. (You know who I root against in every election? Nate Silver. “My numerical science says it’s 50/50!” Thanks, science! What a staggering improvement over qualitative observation and intuition! Defund the humanities!) Here the continuity between magic and science is more important than their much-remarked disjunction, as both are attempts to net the extraordinary complexity of the actual in predictable and intelligible patterns. The sane and tasteful editor Ellen Chandler warns the maddened occultist writer Simon Magnus in Major Arcana,

“The problem with the occult is that it’s no better than the science it claims to reject. It’s just imitation science. It’s all false precision, like Biblical literalism, which itself wouldn’t have occurred to anyone before the Scientific Revolution, before literal scientific fact displaced allegory as the most privileged form of truth. All your numerology—your 78 cards, your 22 paths, your 12 houses, your 10 emanations, your four this and three that and two of the other thing—it’s harder to memorize than the periodic table. It’s not art. It’s too mechanical to be art. I mean, it’s fine if the artist uses it as an arbitrary structure, uses it parodically. Humor’s a passion, too. To use it in earnest, though, to manipulate numbers and think that will change the world—”

Anyway, the YouTube astrologers are now at sea, all over the (electoral) map with their predictions, unable to come to any consensus, cherry-picking evidence both astral and political, and plainly influenced by their own partisan biases. For example, I have seen some use the candidates’ birth charts and some use the U.S.’s birth chart to make their predictions. But why not use the birth charts of the swing states? Why not use the birth charts of the most important counties in the swing states? Why not use the birth charts of the swing voters in the swing states who may decide the election? We live in a reality too complex for easy reduction to a few predictable variables, whether one’s method is science or magic.

(I believe the universe willfully eludes these attempts at regularization. Situational irony is a built-in principle—an irony, while familiar to the artist, that often befalls both magician and scientist.)

I still think astrology is a fascinating and worthwhile method of interpretation, particularly self-interpretation and the interpretation of personality in general, as well as a suggestive guide to collective and ambient mood. I don’t know Smith or McClay’s charts, e.g., but I do know my own, and I know therefore on a symbolic level that I am consumed both by an overweening revolutionary impulse and by a drive to peace and comity. This is why I can’t write in tones either as cutting as his or as diffident as hers, but must sublimate the one as the other and vice versa. Interpretation, as every true critic grasps, is an art, not a science. Thus, for example, an astrologer says that Harris will win because (zodiacally speaking) she is about to experience a positive peak period, and that Trump will lose because he is about to experience a negative peak period. But is this not potentially a weak misreading? Does anybody get the sense that Harris wants to be president? She’d probably be happier doing something else! Trump, meanwhile, could be elected and preside over World War III or a global depression—a negative peak experience, I think we can all agree. This is not a counter-prediction on my part but an illustration that we are dealing with unfathomably complex human affairs. They lend themselves to a plurality of interpretations but not to any science, occult or empirical, of future-casting. The Bible says to forego fortune-tellers and simply to have faith—this may in the end be the sounder advice.

Snares abound on every side, however. Ludic shock tactics are no more reliable a guarantee of artistic quality than is a strenuous seriousness. Can you tell I saw The Substance this week? Hateful Eurotrash, a disgusting waste of everybody’s time. (Why is every movie two hours and 20 minutes, by the way? I recommend 90 minutes for a spectacle that is supposed to be distinguished by its intensity, lest our aesthetic receptors grow as numb under prolonged sensory assault as our asses when we are seated too long.) The Substance is the worst of both worlds, really, too respectable and too trashy, since it’s imprisoned in its own self-conscious historicity with all its distracting allusions to everything from Sunset Boulevard and Mulholland Dr. to The Fly and The Thing to The Shining and Carrie, as well as too obsessed with outraging the viewer to play either its irony or its pathos straight enough to allow a complex emotional response. One might have wrung generous laughter and tears from the viewer with the monstrous heroine’s concluding plea to her own audience, “I’m still me,” but no, we had instead to be drowned in blood too fake even to be repulsive. The film is more dehumanizing to its heroine than is the society it ostensibly condemns for overlooking her. To redeem both French and arthouse cinema, only compare The Substance to The Beast, still the best film I’ve seen this year, a much more sensitive and imaginative treatment of some similar themes—and other and arguably richer themes as well.

On the theme of globalization, I should probably repeat here what I said about this week’s official confirmation that the controversial Compact magazine has received funding from George Soros. An anonymous reader, after praising Compact, asked me what I thought about the revelation. I replied:

Yes, there’s no hidden agenda at Compact, and their cultural coverage is admirably diverse, as are the various expressions they’re willing to give their basic political orientation. Does any other single journal publish a range of political and cultural commenters like Marco Rubio, Chris Rufo, Helen Andrews, Leon Wieseltier, Thomas Fazi, Ryan Zickgraf, and my excellent Substack subscribers Ross Barkan and Sam Kahn? I do think they’ve gotten less interesting and more sectarian since their debut, since Ahmari decided to wage war on the Nietzscheans. Would they publish those Nick Land pieces today? I understand the strictly political case against a certain Nietzscheanism—honestly, I agree with Rufo’s latest polemic against “racialism left and right” and am glad they published it, typical as it may be coming from “dark whites” like us—but from an artistic and philosophical perspective you can’t just be a Catholic conservative, you have to undergo the vertigo of modernity. And from an American perspective you have to be at least a bit of an individualist—or why did we leave the Old World in the first place if only to rebuild its despotisms here?

The Soros funding tells us more about Soros than about Compact. It is only surprising to the less sophisticated populists who think Soros is on “the left” in any world-historical sense, who don’t hear the anti-communist connotation of the phrase “Open Society.” Of course he’d work with Catholic social democrats to push his agenda of a managerial state actuated under the cover of a pseudo-independent civil society. He’d be a fool not to. While I’m sure he’d prefer liberals who would be friendlier to the eugenic part of the agenda, the overall Catholic idea of a bureaucratic clerisy overseeing a restive laity does not conflict with his political model beneath the latter’s cosmetic layer of NGO-ism secretly representing state interests. And to be fair to Soros, I’m sure he is personally interested in intellectual pluralism, as cited in the Vanity Fair article. If he wants to demonstrate this commitment to pluralism even more overtly, he should give me some money!

As a writer, I hope for the immortality of my work, for writing my version of War and Peace or Leaves of Grass. At the very least, I don't want to become the answer to an extremely difficult trivia question.

I’ll forgive the panning of The Substance (although I fully agree that few films deserve to be longer than 90 minutes), but I note the artful dodge of what made the Smith/McClay contretemps noteworthy in the first place. Smith insisted on framing his disagreement with McClay in personal terms, arguing that her claims amount to a “box of poison” deserving “real hatred”. McClay’s stated preference for not writing about people she dislikes lest this warps her judgement sounds more prudent, if less fun. The question of when, and how, to write out of hatred seems to be more immediately relevant to our parasocial times than speculation about whose name will be remembered 200 years hence.