Boris Groys, The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-Garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond

an essay in postutopian consciousness

A literary essay crossposted from johnpistelli.com

[This essay was originally published on March 31, 2021. In the interests of two-posts-a-week scheduling consistency—a book review every Friday and a Weekly Readings newsletter every Sunday—I’ve decided that if I don’t have a new essay to post on a Friday, I will simply take the opportunity to resurface something from the eight-year archive of over 400 pieces at my main site, since there’s no reason to think most of my Substack audience has read everything or anything in that archive. I chose this particular essay because it recalls our discussion of totalitarian aesthetics in Weekly Readings #30 and because it offers a glimpse of my critical, political, and artistic trajectory—something I hope it’s not presumptuous to assume new subscribers might be interested in.]

Back to Boris Groys—we’ve been here before. The Russian-born art theorist’s first major book appeared as Gesamtkunstwerk Stalin in German in 1988 and was published in Charles Rougle’s English translation in 1992—“[a]s communism collapses into ruins,” or so the jacket copy proclaims in the present tense. The book’s very appearance, thin as a volume of poetry, tells us that it is a work of aesthetic philosophy, not art history. Groys’s sweeping and summary treatment of individual artists and artworks may therefore annoy the historian or connoisseur, but for an amateur such as myself, who reads all nonfiction as philosophy and all philosophy as literature, it more than serves.

A little intellectual autobiography, if you’ll indulge me, will wind through my review. I came to this book over a decade ago, led by citations in Peter Y. Paik’s From Utopia to Apocalypse, a brilliant critique of the utopian project as materialized in classics of superhero comics, anime, and science fiction cinema. I was drawn to Paik’s book for its counterintuitive readings of Alan Moore’s Miracleman and Watchmen as conservative cautions against crypto-gnostic leftist world-making; I was drawn in turn, through Paik’s study, to The Total Art of Stalinism because I was just starting a doctoral dissertation to defend the autonomy of art from its leftist critics.

I had already read Peter Bürger’s Theory of the Avant-Garde, or some of it, which, if I recall, posits a distinction between modernism and the avant-garde, even though these two tendencies have been lazily grouped together. For Bürger, the avant-garde (think Bauhaus, Futurism, Constructivism, etc.) had the admirable ambition to overcome the autonomy of art by generalizing art as the total aesthetic recomposition of the state and civil society. Modernism, by contrast, intensifies art’s autonomy by creating artworks about their own form, which turns art in on itself and away from the public. Bürger, a Marxist, laments the failure of the avant-garde and scorns modernism as just more bourgeois art-for-art’s-sake ideology. I read his theory against the grain, though, and applied it to English and Irish literature by seeing the likes of Pater, Wilde, Joyce, and Woolf as admirably refusing the imperial role of realist-novelist-qua-social-commissar sermonizing the public on its moral duties, an abdication that paradoxically makes the reader of modernist novels a more self-conscious because unconscripted ethical agent.

For Groys, on the other hand, the avant-garde succeeded and in the process swallowed up both realism and modernism. Groys claims that socialist realism in Stalin’s USSR was not, as is commonly assumed, the enemy of the avant-garde but rather its successor in the agency of remaking society:

Under Stalin the dream of the avant-garde was in fact fulfilled and the life of society was organized in monolithic artistic forms, though of course not those that the avant-garde itself had favored.

While Groys seems lukewarm toward Hegel, his method is nonetheless dialectical. He shows how avant-garde art, socialist realism, and what he calls the “postutopian art” of the post-Stalin period are three distinct stages of art history, each of which grows out of its precursor’s inability fully to realize its own insights.

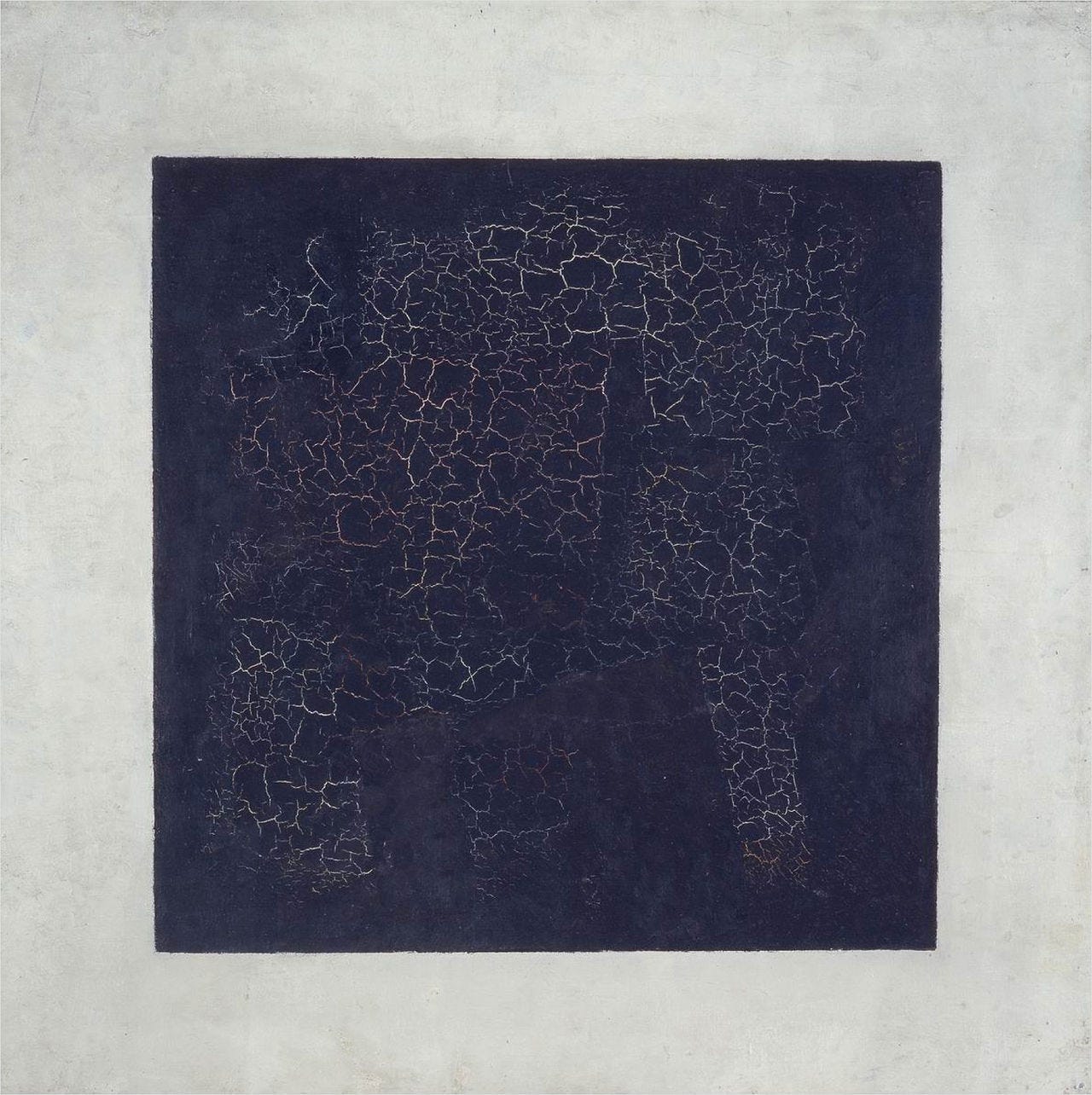

Avant-garde art begins from this premise: with the evanescence of religion, modernity has dissolved the metaphysics that held the world together as an object of the artist’s mimesis. The artwork should in consequence formalize its own emptiness of empirical content by becoming what Groys, glossing Malevich’s Black Square, calls “a sign for the pure form of contemplation, which presupposes a transcendental rather than empirical subject,” a “nothing” that manifests “the pure potentiality of all possible existence that revealed itself beyond any given form.” From this rarefied iconoclasm comes the conviction that humanity is now free of the illusory images that had imprisoned it before modernity melted all that was solid into air and is therefore ready to begin life again from an “absolute zero” to be organized into the substance of the everyday by the artist. Hence the revolutionary sympathies and totalizing ambitions of the Russian avant-garde in the 1920s.

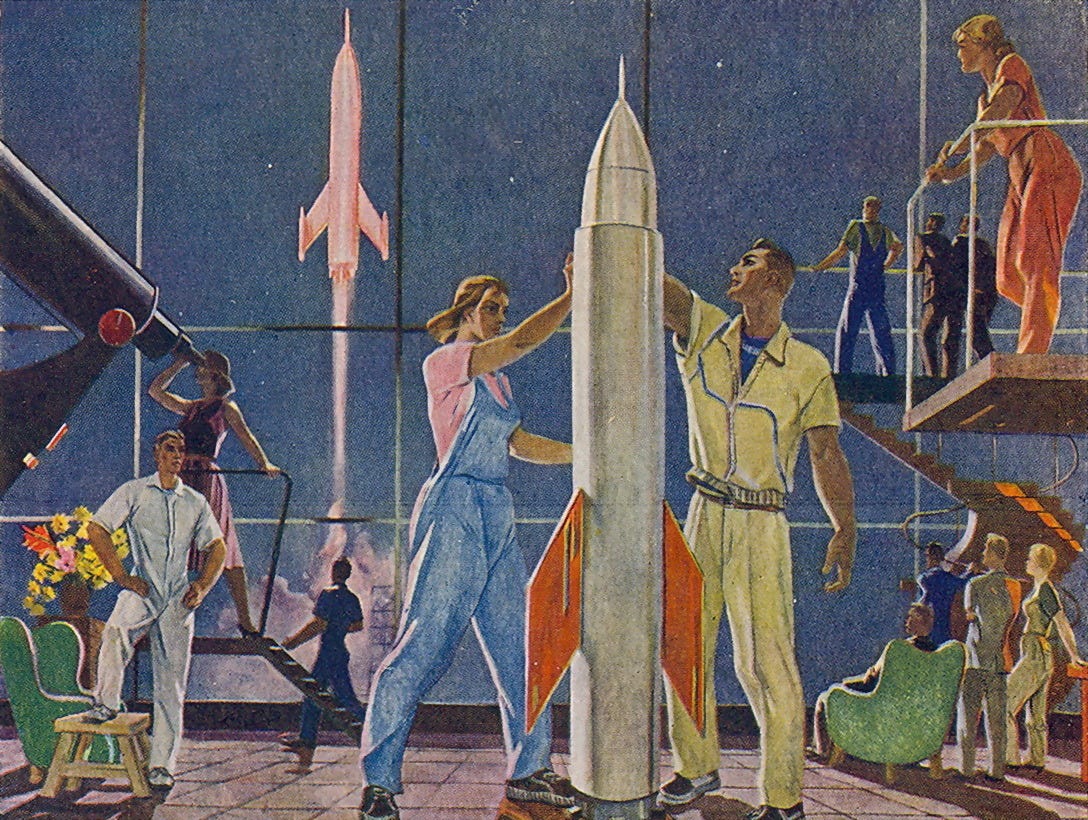

Revolutionary art, however, was still somehow just art; it takes a statesman to reorganize the state and everything in it from top to bottom. Stalin, therefore, becomes the ultimate total artist, alone able to realize the avant-garde’s dream. The art he promoted—socialist realism, with its traditional form and idealized content—looks regressive, Groys argues, only if you miss its point, which is its dramatization of the “demiurgic” activity that is the Stalinist hero’s reshaping of society, always under threat by the counter-demiurge of the wrecker. The avant-garde’s transformation of artistic form is realized as the content of socialist realism; thus, the movements are in ideological continuity:

Although the design of the avant-garde artistic project was rationalistic, utilitarian, constructive, and in that sense “enlightenist,” the source of both the project and the will to destroy the world as we know it to pave the way for the new was in the mystical, transcendental, “sacred” sphere, and in that sense completely “irrational.” The avant-garde artist believed that his knowledge of and especially participation in the murder of God gave him a demiurgic, magical power over the world, and he was convinced that by thus crossing the boundaries of the world he could discover the laws that govern cosmic and social forces. He would then regenerate himself and the world by mastering these laws like an engineer, halting its decline through artistic techniques that would impart to it a form that was eternal and ideal or at least appropriate to any given moment in history. […] The avant-garde was perfectly aware of the sacred dimension of its art, and socialist realism preserved this knowledge. The sacred ritualism of socialist realist hagiography and demonology describes and invokes the demiurgic practice of the avant-garde. What we are dealing with here is not stylization or a lapse into the primitive past, but an assimilation of the hidden mystical experience of the preceding period and the appropriation of this experience by the state.

Socialist realism, however, reaches a limit of its own: in a word, reality. As Soviet culture confronted its increasingly obvious failure to realize the promised utopia after Stalin’s death, it generated official and unofficial versions of an anti-utopian art, which Groys, citing Solzhenitsyn, sees as conservative, nationalistic, and in its own way contiguous with avant-gardism since it too claims absolute access to the real.

The more productive post-Stalin aesthetic is not anti-utopian but postutopian. Similar to western postmodernism, and probably influenced by it as Groys allows that Russian artists were reading Barthes and Foucault by the ’70s and ’80s, postutopian art exposes utopia as a simulacrum made of signs, a constructed grand narrative without final or transcendental authority. But postutopian art also goes beyond postmodernism, which Groys judges to be trapped no less than anti-utopian conservatism in the avant-garde quandary, given postmodernism’s iconoclast mission to purge humanity of semiotic illusion. The postutopians don’t imagine that utopia can be dispelled by rational critique à la Barthes’s debunking of myth, and so their art proffers utopian visions and the critique of utopian visions in a single gesture:

Postutopian art incorporates the Stalin myth into world mythology and demonstrates its family likeness with supposedly opposite myths. Behind the historical, this art discovers not a single myth, but a whole mythology, a pagan polymorphy; that is, it reveals the nonhistoricity of history itself. If Stalinist artists and writers functioned as icon painters and hagiographers, the authors of the new Russian literature and art are frivolous mythographs, chroniclers of utopian myth, but not mythologists, that is, not critical commentators attempting to “reveal the true content” of myth and “enlighten” the public as to its nature by scientifically demythologizing it. As was stated above, such a project is itself utopian and mythological. Thus the postutopian consciousness overcomes the usual opposition between belief and unbelief, between identifying with and criticizing myth. Left to themselves today, artists and writers must simultaneously create text and context, myth and criticism of myth, utopia and the failure of utopia, history and the escape from history, the artistic object and commentaries upon it, and so on. Just as Keyserling predicted when he said that he was not worried about Stalin and Hitler, because eventually all Europeans would enjoy the rights reserved to these two men alone, the death of totalitarianism has made us all totalitarians in miniature.

This is remarkably congruent with the thesis of my doctoral dissertation, give or take that shock in the last sentence, which doesn’t become less true because of how provocatively Groys phrases it. I didn’t see that then, though. A dirty little secret of academe is that one builds a bibliography by reading quickly and partially, so I applied myself to this book’s introduction and first chapter and then skimmed the rest without really understanding his point about the postutopian and therefore not recognizing that it was my point too.

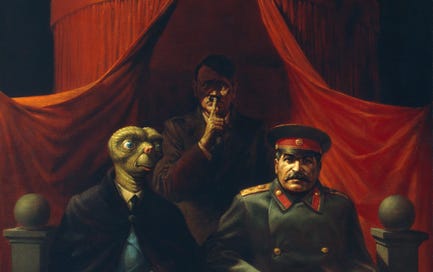

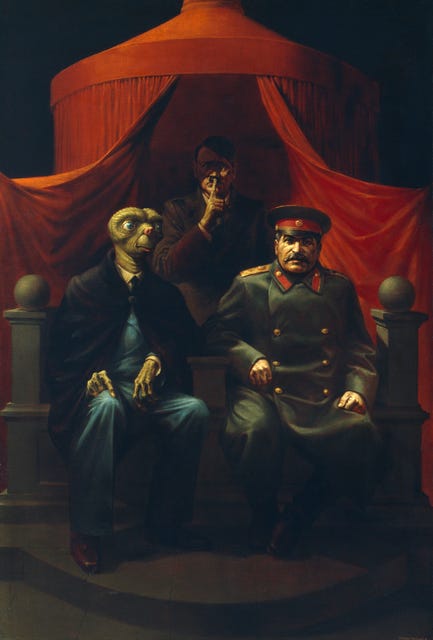

Luckily, the imagination—not my imagination but the imagination—can build castles from rudiments. Everything I couldn’t say in my dissertation I poured into a novel called Portraits and Ashes that dramatizes in both form and content the final phases of Groys’s argument without my having comprehended it rationally. (I put Malevich’s Black Square on my book’s cover.) It is a novel about artists, considered only as metonyms for free human beings as such, who have to learn to remake themselves in conjunction with the world, rather than forcing their poiesis on recalcitrant matter or a docile public. The intense romantic realism of the novel’s style, alternately gritty and rhapsodic, theoretical and vulgar, raises this postutopian doubleness—the vision and the critique of the vision, at once and as the same thing—to the level of form. Granted, I am American, petit bourgeois, and doubtless too sincere. Groys’s main example of postutopian art, by contrast to my romantic aesthetic, is the witty painting by Melamid and Komar that adorns his book’s cover: a stolid realist portrait of the Yalta conference with Spielberg’s E.T. sitting in place of Roosevelt and Hitler behind Stalin and the alien with a shushing finger to his lips. About what does Hitler enjoin silence? Groys explains:

In their work The Yalta Conference, Komar and Melamid create a kind of icon of the new trinity that governs the modern subconscious. The figures of Stalin and E.T., which symbolize the utopian spirit dominating both empires, reveal their unity with the national-socialist utopia of vanquished Germany. It should be observed here that in all their art Komar and Melamid proceed from this inner kinship between the basic ideological myths of the modern world. Thus in one interview Melamid maintains that the common goal of all revolutions is to “stop time,” equating in this respect Malevich’s Black Square, Mondrian’s neoplasticism, Hitler’s and Stalin’s totalitarianism, and Pollock’s painting, which “generated a notion of individuality beyond history and time; powerful as a tiger, it will destroy everything just to be left alone. It is a very fascistic concept of individuality.”

20th-century art and politics has been all of a piece, therefore, from Soviet socialist realism to Russian and American avant-garde painting to German fascist politics to U.S. mass culture. In every case, art slips its leash, colonizes the polis, ends history, and reveals history always to have been an aesthetic construction. (The insertion of Spielberg’s schmaltzy little alien prophesies how American pop-culture fantasy, with its misleadingly misfit heroes who in fact inspire allegiance to the rights- and recognition-bearing ideal of America, becomes the equivalent of socialist realism for the U.S.-led neoliberal empire.) The genius of the postutopian artists, though, is that they are the first artists to grasp both utopia’s inevitability and its danger and to produce it as such in their art as a pastoral care for the utopian imagination rather than an attempt to eliminate it, since all such attempts are doomed instead to repeat its calamities. From that vantage, Groys ends his book with a mocking dismissal of French theory’s pretense to have exited this modern dilemma:

Deleuze and Guattari, of course, think that they are once and for all rid of the “subject” and all of “consciousness” and mythology. All they are doing in reality is repaving the way for the “engineers of human souls,” the designers of the unconscious, the technologists of desire, the social magi and alchemists that the Russian avant-gardists aspired to become and that Stalin actually was.

Anti-essentialist anti-humanism—at least in part what we used to call postmodernism, at least in part the thing we’re now calling “wokeness”—is continuous with the avant-garde desire (which it officially disavowals) to clear the ground of nature and humanity and rebuild a “new man” in the ruins—a desire that serves in the end the powers and principalities of the modern world, including some of the most destructive. But Hitler says, “Keep it to yourself.”

Great post.