A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

This week I published “Them,” the latest chapter of my serialized novel for paid subscribers, Major Arcana. It’s part of a diptych of chapters on gender politics in a late-2010s public school. The next chapter, coming Wednesday, will spill blood in the hallways, even as we contemplate the possibility of nullification surgery. Please subscribe today!

For today’s post, I wasn’t sure what to write, but then I remembered an old piece I wrote for Tumblr over two years ago, which I’m sure no one read at the time; it forms such a good pendant to my recent trilogy of posts about artists-intellectuals and violence that I thought I’d put it here with some updates and annotations. Then, just this morning, a reader wrote in to Tumblr to ask what Major Arcana’s most fascinating character, Ash del Greco, would think about Israel-Palestine. I decided to respond here rather than on Tumblr, where my paid subscribers are guaranteed to see it and where my free subscribers can get a sense of how carefully I’ve thought about a novel I’ve admittedly written rather quickly. Please enjoy!

Never Get the Answers Right: Epilogue on Writers and Violence

In 2021 I had a regular Tumblr feature called “Audiovisual Monday,” where I would post a YouTube video and let it inspire some comments of my own. The video that provoked the post below was an interview of about 20 minutes on the Russia Today YouTube channel between Alan Moore1 and Sophie Shevardnadze. Tumblr is strangely vague about dates, but I think I posted this late in 2021. The RT channel and all its content was deleted from YouTube a few months later during the wave of “information control” that came with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It no longer exists on the English-language internet, that I can find; this article summarizing it and quoting some highlights is all that remains. Nevertheless, the most important point for me was Moore’s regret about the way the icon of the V for Vendetta mask helped to inspire mass violence. I didn’t mention in the original post what fascinated me about this expression of regret.

The reason: when I was employed as an adjunct professor in the University of Minnesota English department, I was often tasked with teaching a class called Literature of Public Life. (“But I don’t believe in ‘public life,’” I always wanted to tell them.) It was what they used to call a “service-learning” class and what came to be called a “community-engaged-learning” class.2 In short, the students would not only participate in the class but would also, under the class’s auspices, have the option to volunteer with a set of carefully “curated” non-profits in the city—everything from a charter school to a domestic violence shelter to a phone service for the distressed. I have nothing against the idea of students participating in such activities. Some of the organizations did good work, and some struck me as scammy; but either way the experience, for students who had often never left the suburbs before going to college, was valuable.

Such activities have nothing in particular to do with literature, however. I never knew what books to teach. I taught different books almost every time. I never did what so many of my colleagues did, which was to choose literature of an overtly activist bent or texts of a fashionable contemporary “social justice” nature (Between the World and Me, for example, or Braiding Sweetgrass). I figured I would assign books to give students a sense of public life’s actual difficulty and complexity, its uncertain or even dangerous relation to private life. One book I taught over and over again in that class was My Ántonia. I take its elegaic Virgilian erotic reverie over the immigrant earth mother on behalf both of the straight male narrator and the gay female author to address the real experiential promise and real ethical danger of trying to be in “service” to the disprivileged “other.” I also liked Sula for that class: Toni Morrison may have come to believe in public life, but Sula Peace certainly doesn’t. I once taught Lolita, though Disgrace would have been more to the point—and even likelier to get me fired.

The first time I taught the class, I designed the syllabus around changing western definitions of the ideal sovereign member of a state, and around the genres that best correspond to these definitions, from “monarch” (tragedy) to “citizen” (Bildungsroman) to “rebel” (pop-culture science fiction).3

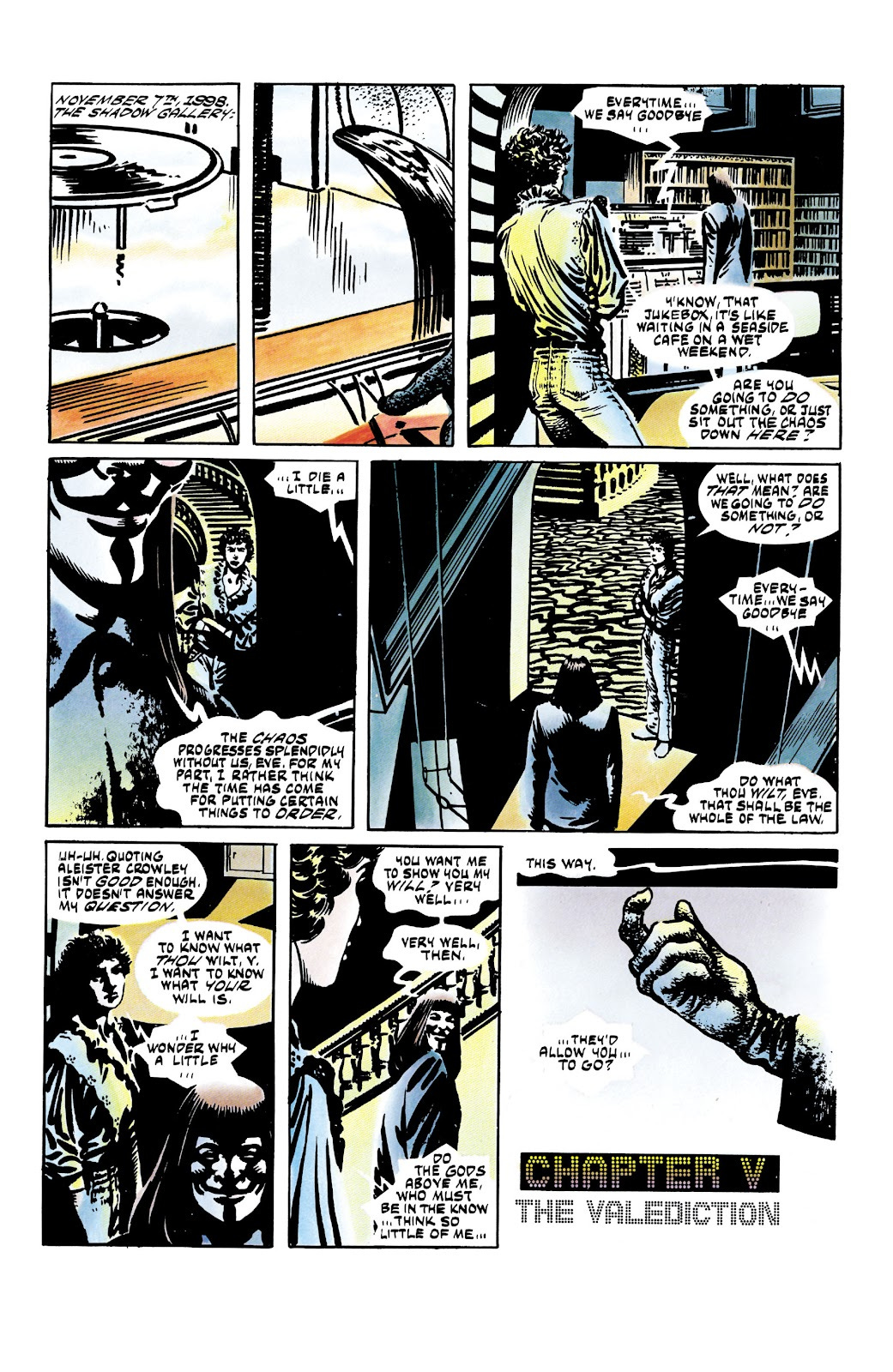

As part of “rebel” division, I taught Moore’s V for Vendetta. Rereading it for the first time as a full-grown adult, I found it more of a literary disappointment than I’d remembered, ideologically confused and compromised by genre nonsense. I probably wouldn’t have taught it again anyway. But I do remember the final days of the course, when students presented their final essays. One girl referred to V for Vendetta in an essay that also mentioned then-popular public protests. As the graphic novel does raise the question of armed struggle, despite Moore’s pacifism, I asked her straightforwardly, “Do you believe in violent revolution?” Without blinking her wide ingenuous eyes, eyes that seemed to me (even if this is patronizing) to be still essentially the eyes of a child, she said, equally straightforwardly, “Yes.” This is not the affect I hope to inspire in the classroom, so that was it for V for Vendetta as far as I was concerned. Back to Willa Cather!

I was naturally interested, then, to see that Moore had the same regrets about writing his book as I had about teaching it. I wrote, therefore, the paragraphs that follow, just before the wars of the present were launched. I present it unrevised, though annotated:

And for our audiovisual Monday, I just found this interview with Alan Moore on RT from only two months ago. I’ve been reading William Blake—working my way through the Norton Critical Edition, which contains the illuminated books in their entirety, with plenty of other odds and ends—and went looking to see if YouTube had Moore’s spoken-word performance about Blake, Angel Passage, which I’ve never seen anywhere in any format. But they only have the final track, where Moore declares of Blake, “It’s not enough to study or revere him, only be him,” about which I’m not entirely sure.4 I have my un-Blakean side too. I’ve never seen an angel or summoned a demon.

Why do occultists always summon demons, by the way? Do they also invite murderers and rapists to their homes on the material plane? If the one, why not the other? In truth, I went to Catholic school; I saw The Exorcist very early in life and then many, many times after that; so I will not be calling down the powers of the air.5

Anyway, esoteric Twitter microcelebrity Logo Daedalus recently complained that no one talks about James Joyce’s essay on Blake. But Richard Ellmann talked about it in his mammoth, landmark biography of Joyce, contextualizing it alongside its companion piece on Defoe. I wrote in my essay on Ellmann:

Synthesizing Defoe’s realism with Blake’s romanticism (“While he took pride in grounding his art like Defoe in fact, he insisted also with Blake on the mind’s supremacy over all it surveyed,” summarizes Ellmann), Joyce held that the artist’s duty was to transfigure truth in the crucible of his imagination and produce a new world out of this one. This act, which both preserves the world and inspires us to change it, which saves the was and incites the will be, what Stephen Dedalus calls “the postcreation,” cannot be achieved on the basis of mollifying lies or blunted language.6

Realism and idealism, naturalism and symbolism—for that matter, Athens and Jerusalem. The identity of opposites held together by the sustaining tension of the artwork, the radiant force-field of aesthetics.

What I find remarkable about the above interview with Moore is that exactly halfway through it, he gently repents having popularized the Guy Fawkes mask7 in V for Vendetta because, in his judgment, the anarchist hackers of Anonymous, who’d adopted it as their symbol of revolution, recklessly incited civil violence in the guise of liberation during the Arab Spring.

Speaking as we were of Irishmen, I here thought not of Joyce, who tempered his Blakean idealism with Defoe’s realism, but of Yeats, who really was trying to be Blake; and as Blake at first hailed the revolutionary spirits of 1776 and 1789 in America: A Prophecy, so Yeats, in Cathleen ni Houlihan, dramatized the avatar of Ireland calling her sons to sacrifice themselves to free the captive land from the English, a bloody summons the poet would live to regret in “The Man and the Echo”:

All that I have said and done, Now that I am old and ill, Turns into a question till I lie awake night after night And never get the answers right. Did that play of mine send out Certain men the English shot?

Do these tragic lines—which I recall Christopher Hitchens applying to himself after a young soldier inspired by his writing was killed in Iraq—mitigate the writer’s responsibility? In his little book on Blake, the Christian apologist Chesterton, who appreciates Blake’s opposition to materialism but is contemptuous of his gnosticism, comments with bland irony,

like most of the men of genius of that age and school, like Coleridge and like Shelley, he seems to have been slightly sickened with the full sensational actuality of the French tragedy; and somewhat unreasonably having urged the rebels to fight, complained because they killed people.

Then again, Chesterton also says in an aside that “witches and warlocks” were “somewhat excusably” killed in European history, which returns us to the warlock Moore’s regrets. But he never portrays a successful political revolution in his work, only a mental and spiritual one. That’s probably as much as poets and artists should advocate, at least if they don’t want to “lie awake night after night.”

Character Counts: Ash del Greco Beyond the Novel

A reader of my novel, Major Arcana, writes in with a question: “What would Ash del Greco’s take on the ‘Free Palestine’ movement be?” This is one of the most interesting variations on the old creative writing exercise, “What would your character eat for breakfast?” (Ash del Greco’s stomach hurts all the time; she doesn’t eat breakfast.) I used to have a Nabokovian contempt for such questions—

INTERVIEWER

E. M. Forster speaks of his major characters sometimes taking over and dictating the course of his novels. Has this ever been a problem for you, or are you in complete command?

NABOKOV

My knowledge of Mr. Forster’s works is limited to one novel, which I dislike; and anyway, it was not he who fathered that trite little whimsy about characters getting out of hand; it is as old as the quills, although of course one sympathizes with his people if they try to wriggle out of that trip to India or wherever he takes them. My characters are galley slaves.

—and then I grew up, as our chessmaster and lepidopterist perhaps never did. Anyway, Ash del Greco’s not political in that sense. I think she believes in the essentially futility of collective action, if not of all action. She doesn’t think about countries so much. She can appreciate action in the service of an ideal, though. She might find something to admire in the founders of Israel, fearsome fighters claiming territory in the service of an ideal, or, on the other side, in the suicide bombers of the Second Intifada, obliterating their own lives for their cause. Also the novel follows Ash del Greco from ages five to about 23, so it matters which “era” of Ash del Greco we’re talking about. She was impressionable in middle school and early in high school, impressionable and on Tumblr, so she might have had her head turned by a revolutionary commitment. She’s a pretty total quietist by the time we take our leave of her. If I absolutely had to assign “mature” Ash del Greco one position in the current field—if I had to imagine her intuiting a sense of the issue from her 100 open browser tabs and then making a decision—I expect she might adopt the Nietzschean Zionist position that “Dimes Square” seems to have settled on, and not, pace Deanna Havas, because she’s in the witting or unwitting pay of the Likud Party or the victim of an op by its “assets.” She’s just very violently not a sentimentalist. When Jacob Morrow was still around, he would have argued with her about the absolute value of life, but he chose to demonstrate that value in a way that ended his life.

Fun fact in conclusion: in the first draft of Part Three, chapter 3, “Against Novels,” Marco Cohen died in Rafah at the side of a Rachel Corrie stand-in, crushed to death by the same bulldozer. I imagined, but did not write, a passage where Cynthia Ozick scathingly elegizes him as “idolator” and “slummer” (the former is what she called Harold Bloom, the latter what she called Rachel Corrie). My idea was to use this to balance out Duncan McGinnis’s later collaboration with John Berger in Part Two, and I still regret losing the Ozick lines I couldn’t bring myself to write. I was worried that this development would be understood as a political statement I didn’t want to make, however, and changed it when I was getting the first chapters of Part Three ready for publication. I made the change about two weeks before October 7—a rare case of divinatory power abandoning my fiction, perhaps for my own safety. Had Marco Cohen lived, he’d obviously be a leader in Jewish Voices for Peace right now. And, no spoilers, but the possibility that Ash del Greco might feel a certain loyalty to Marco Cohen is all that gives me pause in imagining her as a Nietzschean Zionist.

One reason “nerd culture” has defeated “high culture,” as Erik Hoel argues right here on Substack, is that not enough nerds step through the gate leading from the world of nerdom to the world of high art held open at the border by such figures as the ones I’ve written about in these pages, comic-book writers like Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Grant Morrison, or science-fiction writers like Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison, and Samuel R. Delany. How do you read Moore and not go straight on to Shakespeare and Joyce? How do you read Moore and go back to Superman? I was nerd when I was 12; by the time I was 14, I had become an art fag. This is progress; this is how it should be.

An administrator, I assume, detected the Christian connotation of “service” and decided a word so clear and freighted with tradition had to be replaced by a machinic ideological anti-phrase instead: the kind of phrase that, when you hear it, and even more when you have to say it, harrows up a bit of your soul.

Somebody I went to graduate school with, upon hearing how I’d organized the class, accused me of “Social Darwinism.” I told him I didn’t understand the accusation, since the move from “monarch” to “citizen” to “rebel” is neither biological nor progressive. “I’ll accept ‘right-Hegelian,’” I told him in conclusion, “but not ‘Social Darwinist.’” I also once heard this person call someone a “Zionist running dog,” but I think he was being ironical.

YouTube does have Moore’s older performance pieces, The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theater of Marvels, which sort of enacts his occult initiation, to include his summoning of the demon regent Asmodeus, and The Birth Caul, a Romantic autobiography occasioned by his mother’s death in a “strange hot year that stank of lioness,” and (like his first and second prose novels) a psychogeography of Northampton. I owned these two on CD over 20 years ago, but who knows what became of those artifacts. Here is a complete guide to Moore’s spoken-word catalogue.

I’ve studied the occult more carefully in the intervening years and have a more nuanced understanding of this question now. I would still not seek to put spiritual forces of evil, however understood, at my service. The initiate should be beyond good and evil, I’m sure, and peremptory “demonization” is a risk of its own, but I still think it best not to traffic more than is strictly necessary with certain “energies,” to use a New Age term.

Last week I forgot to mention my petty “gotcha” against Edward Said for misreading Joyce and trying to turn him into a nationalist. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus argues with an English professor about the word “tundish,” which both misunderstand as an Irish word for “funnel.” Stephen reflects:

The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine. How different are the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his lips and on mine! I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language, so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech. I have not made or accepted its words. My voice holds them at bay. My soul frets in the shadow of his language.

Said quotes this in Culture and Imperialism as obvious evidence of the cultural wound the “native” feels before the “white man.” But Joyce is making fun of such notions and warning against such resentments. Pages later, Stephen looks up “tundish” and records the result in his journal:

That tundish has been on my mind for a long time. I looked it up and find it English and good old blunt English too. Damn the dean of studies and his funnel! What did he come here for to teach us his own language or to learn it from us? (sic)

Joyce is here mocking any concept of return to an original or volkish language as the Celtic Revivalists recommended. Instead he dramatizes the randomness and uncertainty of linguistic origins. The final question Stephen asks, with its unconventional punctuation and consequently tangled syntax, shows language to be endemically improper, wandering, and creative; individual speakers and their circumstantial usages make language, not racial or national notions of proprietorship (“his” vs. “mine”). This is the linguistic lesson Joyce, the priest of the imagination, will teach both to colonizer and to colonized. So much for culture and imperialism!

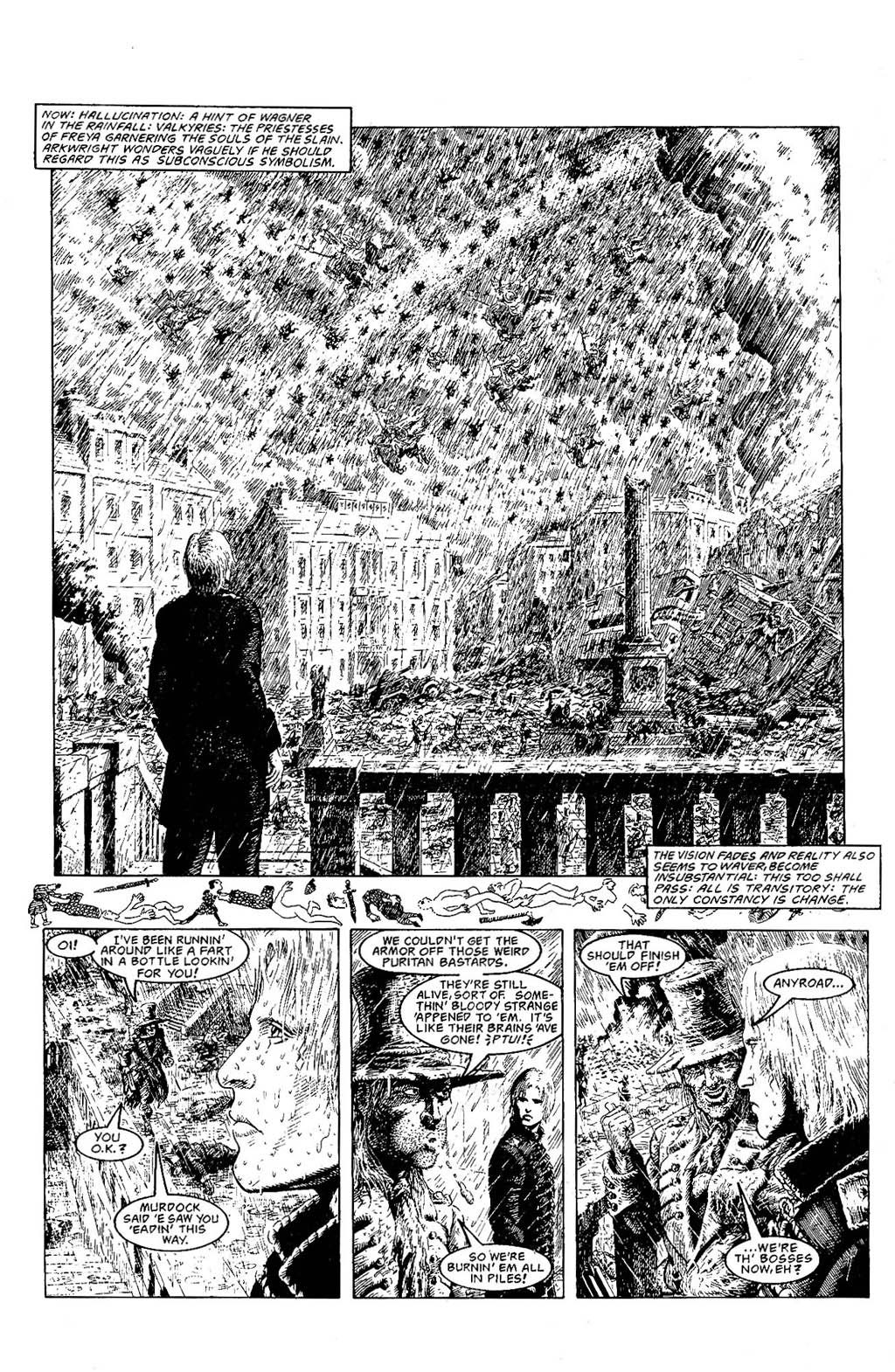

The ideological significance of the Guy Fawkes mask itself needs extensive comment, more comment than I can provide here or even elsewhere. How does a Catholic reactionary become a symbol of progressive revolution? Moreover, consider the often unheralded graphic novel that inspired the British Invasion comic-book writers (Moore, Gaiman, Morrison) and, I believe, inspired V for Vendetta in particular (along with The Invisibles): The Adventures of Luther Arkwright by Bryan Talbot. In that extraordinary book, set in a parallel universe where Cromwell’s government reigns as a puritan dictatorship into the 20th century, we are asked to cheer on (though ambivalently) a Jacobite uprising in a left-right confusion anticipating V for Vendetta’s.

This leads us to the tantalizing concept of “Tory Anarchism.” (In what follows, I reproduce another old Tumblr post; I think I discussed this here once too, but that was about 500 subscribers ago.) This label was self-applied, strangely, by George Orwell, a writer claimed by liberals and conservatives everywhere. I’ve always liked it myself. Edward Said used it on Swift; I once transferred it to Yeats:

It is easy enough to say with Orwell that Yeats was a reactionary and a fascist. Edward Said, who did so much to redeem Yeats for the PC era by praising him in Culture and Imperialism as an anti-colonial poet meditating on Fanonian themes (in another mood, I might enter this into evidence for the fascist tendencies of identity politics), once wrote of “Swift’s Tory Anarchy.” The label might be applied to Yeats, who admired Swift: to his Tory elegy for a shattered culture of wholeness and authority, to his anarchic drive toward the shaping of a soul out of the chaos of experience.

Orwell, Said, Swift, Yeats. What connects the politics of these disparate men of disparate eras who between them cover almost the whole political compass? Consider the etymology of “Tory”:

mid 17th century: probably from Irish toraidhe ‘outlaw, highwayman’, from tóir ‘pursue’. The word was used of Irish peasants dispossessed by English settlers and living as robbers, and extended to other marauders especially in the Scottish Highlands. It was then adopted c. 1679 as an abusive nickname for supporters of the Catholic James II.

The Tory is a reactionary because he is an outlaw of the progressive regime, the regime expropriating his country and trampling his culture with its forward march of progress. “Tory Anarchism,” then, is redundant. There is no real conflict between serving the exiled or prostrated old regime and wishing to bring down the new one, whether you are Irish or Palestinian or one of the British Empire’s inner critics.

But there is no going back—“retvrn” is the idlest of fantasies—so in theory the Tory’s anarchism should at length become less tactical or circumstantial and more of a substantive commitment to individual freedom in a new world, newer than the new regime which displaced the old one. He might still construe these freedoms as better defended by a unitary sovereign than by an oligarchy or bureaucracy, which is what, for this kind of sensibility, most regimes calling themselves democracies pragmatically are. But if the freedoms are the point—and the writings of Orwell and Said may bear this out in the end—then the distance between anarcho-monarchism and liberalism isn’t as far as their feuding partisans imagine. Yeats’s epitaph for Swift:

Swift has sailed into his rest; Savage indignation there Cannot lacerate his breast. Imitate him if you dare, World-besotted traveller; he Served human liberty.

Probably agree that the politics of V for vendetta are too immature to really merit consideration, although what struck me is that V doesn’t so much start the revolution as restart the apocalypse-probably the only really interesting thing in the novel’s politics is the vitalist critique of fascism as a kind of autonomous immune system for 20th century culture maintaining a stultifying stasis even after it was time for it to die. It’s nonetheless essential Moore if only because it straightforwardly erects the Prometheus he spends the rest of his imperial phase deconstructing or ambivalently regarding.