A weekly newsletter on what I’ve written, read, and otherwise enjoyed.

Welcome to the Grand Hotel’s new guests—those who have subscribed since Substack introduced its Notes feature this week. On the one hand, I don’t want to ask you for money right away; on the other hand, a paid subscription will buy you access to Major Arcana, a novel-in-progress that will restore your faith in narrative fiction to sum and save the world. New chapters in text and audio form appear every Monday. The Preface is free to all:

Anyway, I have been experimenting with Notes. I treat it more like a scrapbook or commonplace book than anything else, though we’ll see how the platform evolves. The idea seems, in keeping with Substack’s general ethos of literary maturity, to be a less sensational and more high-minded version of Twitter. There are obvious gains and losses to this approach. What we call cancel culture was a technological rather than an ideological phenomenon, literally produced by Twitter’s hashtag system and trending tab—remember #cancelcolbert? We’re well rid of that. On the other hand, a new type of grand persona, half-prophet and half-lolcow, emerged on Twitter by playing the fool to the massed and easily baited crowd; the rise of such figures seems much less possible here, to the indubitable gain of everyone’s psychological and political health. But think of the entertainment we’ll lose! What can I say? I’m an aesthete.

Speaking of aestheticism, this week’s essay ambulates around the question of artistic genius, with reference to Ralph Waldo Emerson, Pablo Picasso, Anton Chekhov, Ottessa Moshfegh, Andrea Long Chu, and more.

Drink Gasoline: In Defense of Genius

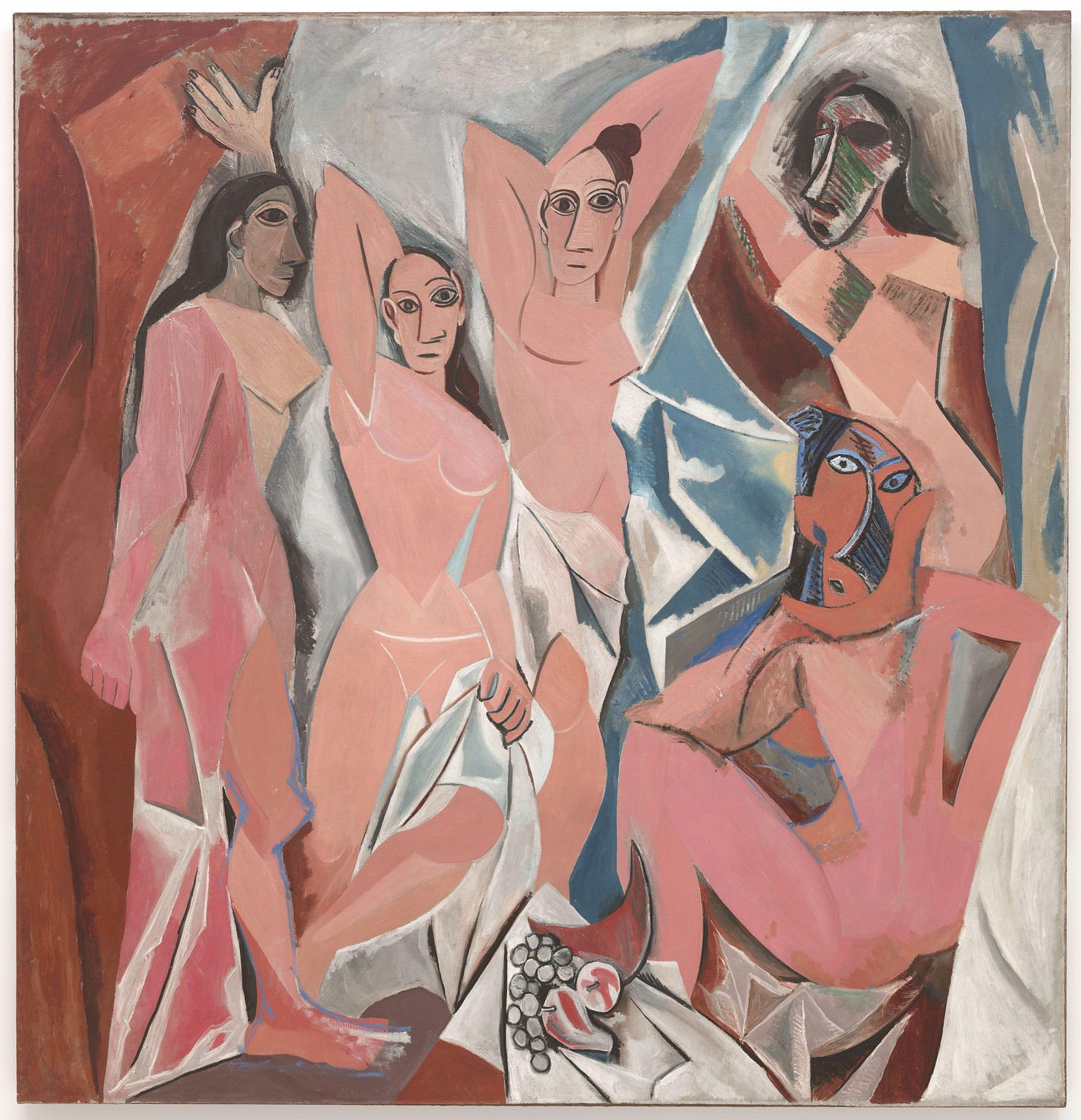

In high-school art class, a friend slightly misquoted Georges Braque to me. When he saw Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon for the first time, Braque said, “It made me feel as if someone was drinking gasoline and spitting fire.” My friend misheard or misremembered this as: “It made me want to drink gasoline.” We immediately agreed that we would seek this effect with our own art.

I like the fake quote better than the real one. The work of art, it implies, makes its viewers want both to fill themselves with fuel and to set themselves on fire, both to contain and to consume the same energy that inspired the artist. It accords with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s sense that the works of genius should serve chiefly to inspire emulous action:

We are too passive in the reception of these material or semi-material aids. We must not be sacks and stomachs. To ascend one step,—we are better served through our sympathy. Activity is contagious. […] I cannot even hear of personal vigor of any kind, great power of performance, without fresh resolution.

I quote from “Uses of Great Men,” the American democrat Emerson’s riposte to the Scottish proto-fascist Thomas Carlyle’s advocacy of “hero-worship.” Jorge Luis Borges summarizes their dispute:

Heroes, for Carlyle, are intractable demigods who—with some slight military frankness and foul language—rule a subaltern humanity; Emerson, on the contrary, venerates them as splendid examples of the possibilities that exist in every man. Pindar, for him, is proof of my poetic faculties; Swedenborg or Plotinus, of my capacity for ecstasy.

Emerson didn’t believe in cultural belatedness. The 19th century, the century that invented history, thought it could only have done so if it had arrived at history’s end, whether in the philosopher’s terminal self-consciousness of reason or in the scientist’s postulate of eventually universal entropy. To these doomsday scenarios and the nostalgia they imply, Emerson’s disciple Walt Whitman said, “There was never any more inception than there is now.”

A misinterpretation of this principle would look like a cultural revolution and its bonfire of vanities. Emerson and Whitman do sometimes both speak in those tones—what is harder to avoid than misinterpreting oneself?—with Emerson reminding his youthful auditors that the grandees of the canon were themselves only ambitious youths and Whitman damning Shakespeare for an aristocrat. Rightly understood, however, these democratic, pragmatic, vitalist, and anti-historicist principles lead to the appreciation of the great works of the past, provided we appreciate what is eternally alive in them and use them to inspire our own answering creativity. This is the democrat’s defense of the canon, its principles laid out before the Civil War, since, as Emerson goes on in “Uses of Great Men,” the democrat’s attack on the canon was well-known then, too:

But great men:—the word is injurious. Is there caste? Is there fate? What becomes of the promise to virtue? The thoughtful youth laments the superfoetation of nature. “Generous and handsome,” he says, “is your hero; but look at yonder poor Paddy, whose country is his wheelbarrow; look at his whole nation of Paddies.” Why are the masses, from the dawn of history down, food for knives and powder? The idea dignifies a few leaders, who have sentiment, opinion, love, self-devotion; and they make war and death sacred;—but what for the wretches whom they hire and kill? The cheapness of man is every day’s tragedy. It is as real a loss that others should be as low as that we should be low; for we must have society.

Is it a reply to these suggestions to say, Society is a Pestalozzian school: all are teachers and pupils in turn? We are equally served by receiving and by imparting. Men who know the same things are not long the best company for each other. But bring to each an intelligent person of another experience, and it is as if you let off water from a lake by cutting a lower basin. It seems a mechanical advantage, and great benefit it is to each speaker, as he can now paint out his thought to himself. We pass very fast, in our personal moods, from dignity to dependence. And if any appear never to assume the chair, but always to stand and serve, it is because we do not see the company in a sufficiently long period for the whole rotation of parts to come about. As to what we call the masses, and common men,—there are no common men. All men are at last of a size; and true art is only possible on the conviction that every talent has its apotheosis somewhere. Fair play and an open field and freshest laurels to all who have won them! But heaven reserves an equal scope for every creature. Each is uneasy until he has produced his private ray unto the concave sphere and beheld his talent also in its last nobility and exaltation.

With his admittedly crude allusion to poor Irish immigrants, Emerson even puts it in race-and-class terms we can understand today. The existence of the canon, Emerson argues, does no harm to poor Irish immigrants just because it doesn’t immediately make them “feel seen.” Wait a while, Emerson advises, and turnabout will take its course, as if he knew in 1850 that scions of those immigrants would in the subsequent century be writing great American novels and getting elected president. He implicitly dismisses as well the intellectual’s perennial fear of overpopulation: if “heaven reserves an equal scope for every creature,” then there can’t be too many creatures.1

All very wholesome and Fourth-of-July, but let’s return to Picasso and the stews of European corruption:

Picasso can be viewed as a monstrous, larger-than-life character in a novel that spans almost a century. His appeal is as a picaresque who left a trail of destruction in his wake: abandonments, betrayals, suicides. We have the vampire, the Andalucían macho, the charismatic manipulator, the sociopath, the narcissist. Then there’s the minotaur who preyed on young girls, the rapist of the Vollard suite, the thief of African tribal masks, the cubist who wrecked the room and patched it back together again. We see the Picasso who laid waste to women, who fed his art with body parts and turned lovers into parodic and pneumatic toys, caricatures of suffering. If not for his art, he’d just be another monster, treating women terribly.2

In response to this, I want to make a case less immediately appealing than Emerson’s democracy of genius, an explanation for what Douglas Murray calls “the genius exemption” in his defense of Picasso: “geniuses are allowed to behave worse than other people.” I would frame this differently, however, since “worse than other people” is in its way too flattering. The genius has often behaved not worse than other people but the same as other people. Does it take the prodigious painter of Guernica to be a cruel womanizer? Doesn’t a cruel womanizer live on every street?

Still, we have the genius exemption because, per genius’s etymology as referring to “a spirit attendant on a person” rather than to the actual person, the genius becomes the locus of the epoch he or she typified, necessarily including its most characteristic faults, not to mention the defects of human nature in general. If we neglect these faults in our study of culture—if we insist they’re only over there, only in the sins committed by that rotten bastard and not entertained in our very own souls—then we will not be able to complete what Jungians call the integration of the shadow. We will be monsters and not even know it.3

Isn’t it secretly disappointing to discover a genius who is too well-behaved? We only really reward good biographical behavior in our hearts if the work is somehow monstrous. Only Beckett could get away with having driven Andre the Giant to school, with having fought in the French Resistance, precisely because his work presents such an abrasive, nihilistic surface. On the other hand, I think of James Wood’s classic essay on Chekhov:

The last line of this letter has always been soothed into English as ‘You have to relinquish your pride: you are not a little boy anymore.’ Rayfield restores a word: ‘You must drop your fucking conceit.’ He reveals the lapses, the mundanities, the coarseness, the sexual honesty which Russian censors and English worshippers removed. His Chekhov, for example, is still philosemitic and a supporter of women’s rights. But every so often his letters show a little hernia of prejudice – ‘Yids’ appear from time to time, and women are verbally patted.

The critic seems almost relieved to discover evidence of the good doctor’s moral faults—the worst faults our own time can conceive: ethnic slurs and an excess of masculine heterosexual appetite—as if to say that a perfectly decent person, a saint, someone who never lusted or loathed in his heart, could never be an artistic genius. Will a saint make us want to drink gasoline?

It wasn’t so much the recent furor over Picasso that brought all of the above to mind, though. Instead, I was thinking about the need for genius after reading Leo Robson’s negative review of Alexsandr Hemon’s new novel. Robson cites an essay where the novelist explains how writing for TV caused him to move away from a literary interest in “language and thought” and toward a commitment to “plotting,” which, he claims, should be “logical” and “algorithmic.”

With Aristotle, I won’t necessarily quarrel with “logical” provided we use the word in a sense broad enough to encompass (for example) “dream logic,” but to describe your vocation as “algorithmic” is practically to beg to be supplanted in it by a machine. The genius, by contrast to the machine (or to the TV writer), does not formulaically recombine given elements but rather “beholds the future in the present”—and this thanks not to the logical ego but to an openness to inspiration from attendant spirits. That Hemon combines what we might call “algorithmism” with moralism is in this instance no accident, since both eliminate the contingency of personality, of soul, from artistic creation.

Then, too, I was thinking about Ottessa Moshfegh. I finally finished one of her books after struggling publicly for years with what I took to be their dull prose despite their audacity of conception. My Year of Rest and Relaxation was my success, of course, probably her consensus masterpiece so far. I still insist it could begin more strongly, but I concede it eventually effloresces into a unique poignance. Once I realized how well the novel pairs with DeLillo’s White Noise—both are written in a deadpan first-person about strange pharmaceuticals, both flirt with romanticizing violence as an escape from the enervations of the everyday, both finally counsel a spiritual embrace of the post- or hypermodern quotidian—I navigated straight to the end. And what an end, a pointed recasting not only of DeLillo’s own remarks about terrorism but also a calculated redemption of Stockhausen’s notorious statement after 9/11. This outrage, the ultimate in amoral aestheticism, shouldn’t work, but it does, and very beautifully.

Thinking about Ottessa Moshfegh also made me think about Andrea Long Chu, who has written the canonical hatchet job on Moshfegh to date.4

Moshfegh describes her writing process as an ecstatic experience of “channeling a voice,” and she has often expressed a desire to “be pure and real and make whatever is coming to me from God.” The epigraph to Lapvona, “I feel stupid when I pray,” is taken from a Demi Lovato song about feeling abandoned by God. But the phrase also recalls Moshfegh herself, who imagines that her “destiny” is to reach into readers and transmit the divine. “My mind is so dumb when I write,” she told an early interviewer. “I just write down what the voice has to say.” In other words, there’s a reason God isn’t listening: He’s busy praying to people like Moshfegh.

In other words, Chu arraigns Moshfegh for taking to herself the traditional trappings of the literary genius Emerson would have recognized, drunk on words whispered in her ear by God. Chu would prefer to this supposed arrogance, this paradoxical arrogance-by-kenosis, what she calls “politics,” commenting, for example, that “Moshfegh has no interest in class critique,” as if it went without saying that she should, or even as if it went without saying that the novelist’s expert eye for class difference were incompatible with critique just because it’s not didactic.

I recently told a room full of aspiring artists with politics roughly akin to Andrea Long Chu’s that it might have made sense to criticize the concept of genius back when it was at least implied to be socially exclusive—to be the sole preserve of whites or men or the upper class or what have you. This hasn’t really been the case for several generations, however; to beat Picasso after all this time is really to beat a dead horse, and women of color like Ottessa Moshfegh don’t hesitate to drink gasoline.

They were professionally worried, my young auditors, about AI, worried about it in a way that made them more open than they might otherwise have been to reconsidering certain ideological presuppositions. So I felt safe in telling them that we need to resuscitate the concept of genius in and for these changed circumstances. “We need a new Romanticism,” I said. The antonym of “genius” is not “democracy.” As Emerson knew, it never was. The alternative to the genius—the alternative to spirits speaking to and through us—is the algorithm speaking in our place.

“There are no common men” may be cold comfort to someone literally starving right now, whether “right now” is 1850 or 2023, but that’s not a circumstance answerable to cultural criticism. Trying to make cultural criticism answer it—trying to make culture answer for it, as if immolating the works of genius could literally keep the poor warm—is the unfailing sign of the demagogue.

I began my class Introduction to U.S. Multicultural Literature by explaining modernism with elaborate reference to Les Demoislles d’Avignon (start around minute 37):

Orwell’s argument against the genius exemption in his essay on Dali is at least valuable for the caveat that putative genius does not in the moment excuse unethical behavior—

One can see how false this is if one extends it to cover ordinary crime. In an age like our own, when the artist is an altogether exceptional person, he must be allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility, just as a pregnant woman is. Still, no one would say that a pregnant woman should be allowed to commit murder, nor would anyone make such a claim for the artist, however gifted. If Shakespeare returned to the earth to-morrow, and if it were found that his favourite recreation was raping little girls in railway carriages, we should not tell him to go ahead with it on the ground that he might write another King Lear.

—but I still maintain that, since almost every active soul eventually behaves unethically, we shouldn’t moralize in retrospect, erupting, for instance, with the knee-jerk exclamation that Orwell himself was a sexist, a snitch, a racist, a homophobe, etc. Similarly, it used to be understood that every American president was necessarily a criminal—the chief enforcer of the law almost by definition has one foot outside the law—which is, paradoxically and precisely, why none should ever be prosecuted. I suspect no good will come from the recent trespass upon this unspoken concession to the bitter truth.

As always, synchronicity abides with me. To think about Andrea Long Chu this week is to think about Blake Smith’s characteristically meticulous dismantling in Tablet of her persona and philosophy. While I don’t really admire her persona or philosophy much more than Smith does, I have been of the “at least she’s honest” school of thought when it comes to Chu, and I believe “On Liking Women” is, whether we agree with it or not, an epochal essay. She isn’t honest, however, in her approach to Moshfegh, demanding of the novelist a legible politics she reserves the right to refuse herself. In her essay on Moshfegh she writes less like a vaunted provocateur and more like your average rent-a-commie complaining that this or that artist doesn’t advance the revolution, as if artists haven’t been listening to this tedious gripe, sometimes at gunpoint, for over a century. (Howard Hampton once called this style of critique “holier-than-Mao.”) I haven’t written at length about Chu, but I do give a sense of where we might differ in my essay on Vidal’s Myra Breckinridge and my essay on Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, the latter of which begins, if you’ll excuse my own provocation, “Feminism and misogyny are the same: both aim to abolish female flesh.”

There was an interesting review by John Banville of a new Rilke biography somewhat recently, in which Banville comes very close to stating (or conceding?) that Rilke /had/ to be an awful person, a real abuser of humanity as it manifests in actual, living human beings, in order to write his poems--not in order to be an artist generally but in order to write those precise, aesthetically & spiritually & psychologically inimitable works that he did. Banville so very nearly says this! And does not.

The 1840s andd 1850s were a time of genius: Lord Kelvin, Balzac, Flaubert.